Each year, more than a million people walk through the cold, dark Rotunda of the National Archives in Washington DC to glimpse the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Called the engrossed copy, the text of the Declaration is handwritten in large letters on parchment that is encased in a frame of pure titanium with gold plating. The document, featuring the signatures of fifty-six members of the Second Continental Congress, is badly faded, but the headline still reads clearly: “In Congress, July 4, 1776. The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America.”[1]

What the majority of visitors don’t know is that the displayed Declaration, so carefully preserved and protected, was old news even in 1776. The engrossed copy wasn’t authorized by Congress until July 19, 1776, and wasn’t signed by most members until August 2. By then, the Declaration had been printed and reprinted in at least twenty-nine American newspapers and one magazine.

On July 2, Congress voted for independence, and two days later it approved the text of its official declaration. The July 2 issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post and July 3 edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette, both Philadelphia newspapers, contained the first official word that “the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS declared the UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES.” Then, on July 5, the full text of the Declaration was typeset and printed in John Dunlap’s Philadelphia print shop with copies quickly dispatched to various committees, assemblies, military commanders and foreign nations.

Breaking news today is practically instantaneous with journalists, bloggers and citizen reporters often competing to broadcast announcements on Twitter, Facebook, cable news, radio and websites. During the American Revolution, even the most critical intelligence could only travel at the pace of the fastest horse or ship, often taking weeks to reach other colonies or countries by treacherous postal roads or sea routes. Nevertheless, the British Empire’s eighteenth-century newspaper network was the quickest way of spreading news, which was still considered fresh on arrival because it was the latest information people had.

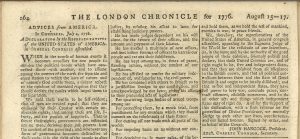

News of American independence reached London the second week of August via the Mercury packet ship, which sailed with important correspondence from General William Howe to Lord George Germain, dated July 7 and 8, at Staten Island. The London Gazette, the official Crown organ, first broke the news in its Saturday, August 10 edition. A 16-word, 106-character, Twitter-esque extract from a Howe letter read: “I am informed that the Continental Congress have declared the United Colonies free and independent States.”

Later that day, the London Evening-Post included its own version of the breaking news: “Advice is received that the Congress resolved upon independence the 4th of July; and have declared war against Great Britain in form.” The same blurb appeared in the Tuesday, August 13 issue of the London Chronicle. On Wednesday, the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser printed “Copies of the Declarations of War by the Provincials are now in Town and are said to be couched in the strongest terms.”

Back in America, independence celebrations were short-lived as the Continental Army suffered crushing defeat after defeat during the New York Campaign. Later that winter, following decisive American victories at Trenton and Princeton, Congress ordered Baltimore printer Mary Katherine Goddard to print a broadside based on the engrossed copy. With this January 1777 broadside, the American public first learned of all fifty-five signers of the Declaration (Thomas McKlean of Delaware added his fifty-sixth signature later in the war).

By 1777, the Declaration was old news, domestically and internationally. It had traversed the globe and been printed in numerous languages by dozens of foreign newspapers and magazines. It was the eighteenth century equivalent of going viral. Attempting to retrace the printing steps of the Declaration in newspapers and magazines is much easier among American publications with the July 6 Pennsylvania Evening Post holding the undisputed title of first newspaper printing. However, across the pond, retracing European news printing steps has been a messy, legend-loaded challenge.

Since at least 2007, the Belfast News-Letter thought it had earned “arguably the greatest-ever scoop” by publishing the U.S. Declaration of Independence before any other European newspaper, and before King George III got word. In 2010, the claim was echoed by the Daily Mail, one of the United Kingdom’s largest daily papers, which listed it as the number one greatest newspaper scoop of all time. Supposedly, the ship carrying the first copy of the Declaration from America to London ran into heavy storms off the coast of Ireland, which caused a detour and resulted in the Belfast exclusive on August 27, 1776.[2]

As they might have said in the eighteenth century: Hogwash.

Having seen and held earlier European newspaper printings of the Declaration, I knew the story–which had been trumpeted on BBC, Wikipedia and at least one book from an academic press–was untrue.[3] One 1776 British newspaper that I knew debunked the Belfast myth was the August 17 edition of the London Chronicle. Unfortunately, the London Chronicle is also often mislabeled for being the first British or European printing of the Declaration.[4]

Based on my research and correspondence with the British Library, it appears that two August 16 newspapers–Public Advertiser and Lloyd’s Evening Post and British Chronicle (both from London)–are the best bets for first European printings of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. They scooped the London Chronicle (and a half dozen other newspapers) by mere hours.[5] The Declaration was printed in Edinburgh, Scotland, on August 20; Dublin, Ireland, on August 22; Frankfort, Germany, on August 23; and Kilkenny, Ireland, on August 24. So, while the London Chronicle lost the scoop by hours, the Belfast News-Letter clearly did not even come close to earning the worldwide exclusive, or the British, or the Irish.

The European list oddity is that it lacks French newspaper printings of the Declaration. That’s because the original copy that the Committee of Secret Correspondence sent to Silas Deane, an American agent in Paris, never arrived. On July 8, the committee sent a copy of the Declaration along with instructions to spread the word through French translation and reprints in the local gazettes, but it was lost in transport. Follow-up correspondence to Deane, dated August 7, arrived in mid-November, but the French were already reading about American independence in the English, German and Dutch newspapers, including the French-language Gazette de Leyde (Netherlands), an important and well-circulated political newspaper, which printed the Declaration in its August 30 edition.[6]

To help future writers and researchers correctly identify the chronology of American and European newspaper and magazine printings of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, I figured I’d maintain a living resource that will be updated as edits and new information are uncovered. Since this list is primarily intended to correct myths about “who printed it first,” I am limiting the American list to those newspapers and magazines published in July 1776. Similarly, the list of European newspaper and magazine printings will be limited to only those that published the text of the Declaration in August 1776. Also, in cases where a newspaper issue date is a range, such as the August 15-17 London Chronicle, only the later date, the date of actual circulation, is provided.

First American Newspaper and Magazine Printings of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, July 1776

- July 6 – Pennsylvania Evening Post (Philadelphia)

- July 8 – Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia)

- July 9 – Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote (Philadelphia)

- July 9 – Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette (Baltimore)

- July 10 – Maryland Journal (Baltimore)

- July 10 – Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia)

- July 10 – Pennsylvania Journal (Philadelphia)

- July 10 – Constitutional Gazette (New York)

- July 11 – New York Packet

- July 11 – New York Journal

- July 11 – Maryland Gazette (Annapolis)

- July 12 – Connecticut Gazette (New London)

- July 13 – Pennsylvania Ledger (Philadelphia)

- July 13 – Providence Gazette

- July 15 – New York Gazette

- July 15 – Connecticut Courant (Hartford)

- July 15 – Norwich Packet

- July 16 – New Hampshire Gazette Extraordinary (Exeter)

- July 16 – American Gazette (Salem)

- July 17 – Massachusetts Spy (Worcester)

- July 17 – Connecticut Journal (New Haven)

- July 18 – Continental Journal (Boston)

- July 18 – New England Chronicle (Boston)

- July 18 – Newport Mercury Extraordinary

- July 19 – Essex Journal (Newburyport)

- July 19 – Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, by Purdie – extract; in full July 26)

- July 20 – Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, by Dixon & Hunter)

- July 20 – Freeman’s Journal (Portsmouth)

- July 22 – Boston Gazette (Watertown)

- July – The Pennsylvania Magazine (Philadelphia, only dated July)

- August 2 – South Carolina & American General Gazette (Charleston – although printed in August, this was a weekly title and in production during the last week of July)

First European Newspaper and Magazine Printings of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, August 1776

- August 16 – Public Advertiser (London)

- August 16 – Lloyd’s Evening Post, and British Chronicle (London)

- August 17 – London Chronicle

- August 17 – Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser

- August 17 – Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (London)

- August 17 – London Evening Post

- August 17 – General Evening Post (London)

- August 17 – Middlesex Journal and Evening Advertiser (London)

- August 17 – St. James Chronicle, or the British Evening Post (London)

- August 20 – Edinburgh Advertiser (Edinburgh, Scotland)

- August 20 – Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland)

- August 20 – Courier de l’Europe (London)

- August 21 – Edinburgh Evening Courant (Edinburgh, Scotland)

- August 22 – British Chronicle or Pugh’s Hereford Journal (Hereford, England)

- August 22 – Public Register: Or, Freeman’s Journal (Dublin, Ireland)

- August 22 – The Weekly Magazine (Edinburgh, Scotland)

- August 23 – Altonaischer Mercurius (Hamburg, Germany, extract; in full August 26)

- August 23 – Francfort Oberpostamtszeitung (Frankfort, Germany, extract)

- August 24 – The Crisis (London)

- August 24 – The Leinster Journal (Kilkenny, Ireland)

- August 24 – Staats- und Gelehrte-Zeitung des Hamburgischen unparteyischen Correspondenten (Hamburg, Germany, extract)

- August 27 – Belfast News-Letter (Belfast, Ireland)

- August 27 – Gaceta de Madrid (Madrid, Spain)

- August 30 – Gazette de Leyde (Leiden, Netherlands)

- August 30 – Göteborgs Allehanda (Gothenburg, Sweden)

- August 31 – Wienerisches Diarium (Vienna, Austria)

- August – The General Magazine (London, only dated August)

- August – The Gentleman’s Magazine (London, only dated August)

- August – The London Magazine (London, only dated August, extract)

- August – The Monthly Miscellany (London, only dated August)

- August – The Scots Magazine (Edinburgh, Scotland, only dated August)

- August – The Sentimental Magazine (London, only dated August)

- August – The Universal Magazine (London, only dated August)

- August – The Weekly Magazine (Edinburgh, only dated August)

- August – The Westminster Magazine (London, only dated August)

These are the known first printings of the U.S. Declaration of Independence in American and European newspapers and magazines. While I believe the American list is fairly comprehensive, I assume there are at least a few more August 1776 European newspaper and magazine printings of the Declaration, but I simply don’t have access to the international archives to confirm. That said, this list will be updated as new information is uncovered.

In addition to my own research of newspaper archives and conversations with institutions, the following sources were used to make the above lists:

- Clarence S. Brigham, Journals and Journeymen: A Contribution to the History of Early American Newspapers (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950), 58-59.

- David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (Harvard University Press, 2007), 70. Note: Incorrectly dates Freeman’s Journal (Dublin) printing as August 24. It is August 22. Correctly cites “British Chronicle” for its first European printing, but does not mention the Public Advertiser. Original source is The Nation, 66 (Feb. 17, 1898), which also omits the Advertiser.

- Stephen M. Matyas, Jr., Declaration of Independence: A Checklist of Books, Pamphlets and Periodicals, Printing the U.S. Declaration of Independence, 1776-1825 (2009)

- British Library: The Burney Collection of 17th and 18th Century English Newspapers

- Thorkild Kjaergaard, Denmark Gets the News of ’76 (Danish Bicentennial Committee, 1975). Note: Incorrectly cites August 17 London Chronicle as first London newspaper printing of Declaration.

UPDATES:

- November 12, 2013: Added a printing by Courier de l’Europe. Hat tip: Will Slauter, Université Paris 8.

- July 5, 2015: Added Pennsylvania Journal, July 10, 1776. Hat tip: Seth Kaller.

[1] “Charters of Freedom Re-encasement Project,” National Archives.

[2] Belfast News Letter (no longer hyphenated like it was in 1776), August 23, 2007. Daily Mail, last updated July 8, 2010.

[3] BBC News Northern Ireland, November 30, 2012. Wikipedia, accessed January 24, 2013 (since corrected); Warren R. Hofstra, ed., Ulster to America: The Scots-Irish Migration Experience, 1680-1830 (University of Tennessee Press, 2011), 15.

[4] Multiple sources cite the August 17, 1776, London Chronicle as the first European, British or English printing, including Wikipedia articles for London Chronicle and Belfast News-Letter, accessed August 22, 2013; Henry Fairlie “The Shot Heard Round the World,” New Republic, July 18, 1988; Thorkild Kjaergaard, Denmark Gets the News of ’76 (Danish Bicentennial Committee, 1975).

[5] Supporting the August 16 date for the first British/European publication of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, other European newspapers, such as the September 2 Kiøbenhavnske Tidender (Copenhagen, Denmark), published the text of the Declaration under the dateline “London, August 16.” Source: Thorkild Kjaergaard, Denmark Gets the News of ’76 (Danish Bicentennial Committee, 1975). While other sources have cited the August 16 “British Chronicle” as the first British printing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, I have seen no book recognize the Public Advertiser.

[6] Committee of Secret Correspondence to Silas Deane, Philadelphia, July 8 and August 7, 1776, Franklin Papers, vol. 22, 502-503 and 553-554.

7 Comments

Outstanding research! Cutting edge work to set the record straight…..and, to keep it updated. Well done.

This is a terrific article, not only for the intrinsic facts it reports but it reminds us that communication among the Colonies (not to mention Europe) was slow and precarious. Yet another reason to keep coming back to this website. Knowing Todd will keep this list up to date, I suspect we’ll also see ‘firsts’ from Delaware, New Jersey, Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina.

Thanks, Hugh and SPM. Slow to us in the 21st century, but probably pretty fast to them. In July 1776, there were no newspapers being published in Delaware or Georgia. The only South Carolina newspaper being printed in 1776 was the South Carolina & American General Gazette, which suspended printing May 31 and resumed August 2 — and it did carry the Declaration of Independence in the August 2 issue. North Carolina is a bit of a black hole in 1776 with no copies of its Gazette in existence, despite a few surviving from 1775 and 1777. There were only 31 or 32 American newspapers, and one magazine, in print at the time, so the Declaration appeared in the only American magazine and all but one or two American newspapers by August 2.

Thanks for putting this piece together and sharing it, Todd. Every once in a great while a happening prompts a “you are there” moment in my mind during which I experience something akin, in some small measure at least, to what they felt at the time. Your discussion did that for me. While reading the piece, I suddenly realized what a significant statement was the Declaration and the danger signing it–and supporting it–put those people in. Of course, I have always known that but my synapses have never made connections quite the same way nor have I ever had the shot of adrenaline as this time. What a rush!

Great reading!

Thanks for an interesting history lesson. I enjoy these by-ways. Have you tackled the unalienable v inalienable question? I’ll be back tonight when I’m not at work to have a look round.

This is an outstanding research!