A musket is not an accurate weapon. That’s a well known fact. But, why is it inaccurate and what can we learn from its shortcoming we can apply to studies of the Revolutionary War battlefield.

There are innumerable variables concerning the musket. To keep this analysis simple most of the variables will be ignored (things such as temperature, humidity, elevation above sea level, variances in quality of the gunpowder, uniformity of the roundball itself, the size of the ball vs. size of the interior of the barrel, etc.).

Basically a musket is a smoothbore weapon much like a 12 gauge shotgun.[1] My test weapon is a standard .75 caliber Brown Bess replica (I wouldn’t shoot an original and nobody else should either). I shoot it with a .69 inch roundball which weighs 476 grains, or one ounce, loaded from a paper cartridge.[2] The velocity of the roundball varies depending on the amount of powder used and how much fouling is in the barrel. But, for our purposes we’ll use the average of 1000 feet per second (fps).

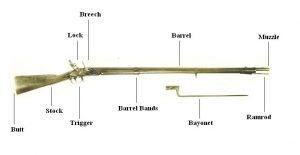

The best target rifle in the world is not accurate if it has poor sights. The Brown Bess, Charleville and other muskets of the period have no sights at all. The Brown Bess does have a bayonet lug to secure the bayonet. The bayonet lug is not an ideal sight but it is on the top of the barrel; so we will consider that a front sight.

Normally, the shooter would look down the barrel and align his rear sight (the sight closest to his face) with the front sight and with the target. This cannot be done with the musket since there is no rear sight. Without a rear sight the shooter’s eyeball acts as the rear sight. That would not be a problem if the eyeball could always be placed exactly in the same place each time the musket was fired. But, it cannot be done.

Normally, the shooter would look down the barrel and align his rear sight (the sight closest to his face) with the front sight and with the target. This cannot be done with the musket since there is no rear sight. Without a rear sight the shooter’s eyeball acts as the rear sight. That would not be a problem if the eyeball could always be placed exactly in the same place each time the musket was fired. But, it cannot be done.

No matter how carefully the shooter places his cheek to the stock his eyeball will not be in the exact place each time. And here small variances make a big difference. All things being equal if the eyeball is placed a mere 1/4 inch above, below, left or right of the ideal sighting position the impact of the roundball will be over 9 inches off the desired point of impact at a target only 50 yards away.[3] In the heat, chaos, and stress of battle, the shooter’s eyeball may be far more than 1/4 inch from the ideal position.

The musket itself is not accurate for a variety of reasons. One reason is the aerodynamics of the big roundball itself. When it leaves the muzzle of the musket at a velocity of 1000 fps it immediately begins to drop due to the force of gravity. At 25 yards it drops only one inch but at 50 yards it drops over 4 inches. At 75 yards it drops 10 inches and at 100 yards it drops over 18 inches. For a target at 125 yards the roundball drops 30 inches.[4] These, of course, would be the figures if the musket could be properly aimed with sights – which as we have seen it is impossible as it has no sights.

Another major problem with accuracy is the soldier himself. To fire at leisure on the target range is one thing. To face an enemy very likely within 100 yards, and perhaps much closer, would be a very different situation. The concussion of the soldier firing on the side of our soldier would certainly interfere with his shooting skills. And, those skills may have been minimal in the first place as live fire practice was not a continuous drill.

Today we think of the infantryman using his rifle, and in a worst case scenario, falling back on his bayonet as a last resort. However, in the 18th century the musket was used to pave the way for the use of the bayonet. It was the bayonet that was the real primary weapon. As it has been said, the musket is a good handle for the bayonet. There’s a lot of truth to that statement.

[1] A musket has a smooth bore barrel. A rifle, on the other hand, has spiral grooves known as “rifling” that impart a spin on the projectile causing it to be more stable in flight.

[2] To load the musket the soldier would take the paper cartridge consisting of the roundball and powder out of his cartridge box and bite off the powder filled end of the cartridge. He would then put a small amount of powder in the pan where the flint lock, when fired, will cause it to flash and ignite the main charge inside the barrel. The rest of the powder the soldier would pour down the barrel and then push the ball and the paper of the cartridge down the barrel with his ramrod. The paper would keep the ball from rolling out of the barrel and also provide a seal between the ball and the walls of the interior of the barrel.

23 Comments

As usual from Mr. Harrington, a fascinating and enlightening article. We’ve been taught that the musket was unreliable, hence, massed formations to concentrate what fire there was. I’ve always wondered how the heck a man fed his family as hunting was a primary source of protein. A deer is one thing but a duck or a pheasant? Did a farmer have a rifle AND musket? Daniel Morgan was the poster boy for riflemen. Despite being slower loading and lacking a bayonet mount (reasons enough to avoid its use) wouldn’t rifle regiments intermingled with musket-bearing regiments be a more effective firing force, at least to wound or kill British officers, which was a common rebel tactic? Was this done as a battlefield tactic? Were Morgan’s successes at Saratoga and Cowpens not recognized for the successful battlefield tactic they were? Lots of questions but I have no doubt this Journal will answer them in due course.

Really interesting question on Morgan’s sucesses being recognized as great battlefield tactics. I see Cowpens touted more often with his use of militia to fire and retreat, fire and retreat, as a tool to break the British ranks and expend their charge so Howard and the Continentals could turn and reverse the momentum. Considered by many the best tactical battle of the war.

On the other hand, his tactics at Saratoga were equally effective yet different. As I understand it, Morgan had the riflemen fire from a distance, retreat so that Dearborn’s Light Infantry could charge in with bayonets and drive any remaining British back. Then the riflemen would come up again and continue their sniping at the British. Some sources indicated the rifle fire was particularly heavy on the officers. I think this battle reflects the tactics you describe with rifle regiments intermingled with musket/bayonet regiments.

there were differences yet similarities in the tactics at each battle. Morgan not only showed good tactical ability but also the ability to modify his tactics to changing situations and win anyway.

Steven, I think they used ‘fowlers’ which were essentially a smooth bore musket that fired bird shot.

Wayne is spot on with his analysis of Morgan at Cowpens and Saratoga.

In the book “a narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier – Accounts of Joseph Plummer Martin, he mentions a British sniper openly taking pot shots at our troops in an open march. Joseph thought it “over a half mile away” and they paid the sniper no mind. A fellow soldier asked the Sergeant if he could expend his cartridge at the sniper which was approved. He shot and the Sniper fell, tho they originally thought he was having fun at their expense until they passed by that spot the next day and the British sniper was still laying where he fell. Let’s say he’s exaggerating at 1/2 mile. Say it’s a quarter mile. That’s still a very long shot so there were muskets that had some accuracy.

Great post!

Don’t forget the trade off for accuracy with a smoothbore is the rate of fire. Experienced soldiers could get off 3 shots a minute. The idea was to fire as often as possible in the general direction of a concentrated and exposed enemy.

Also don’t forget the ‘buck and ball’ cartridge, which effectively turned the smoothbore into a much more accurate and deadly weapon. Check out a video of my 1777 Charleville firing buck and ball at the bottom of this page:

http://twistification.com/charleville/

If I recall correctly, Washington mandated buck and ball cartridges and wanted Continentals outfitted with smoothbore muskets (and their critical accessories-the bayonet). Rifles were not felt to be the most effective instruments of war at the time. They took too long to reload and could not be outfitted with bayonets–but they were used effectively to be sure.

I would love to see more posts about this! I have become quite a smoothbore enthusiast and feel that the effectiveness of this weapon is often understated do to concerns about accuracy.

The musket is very reliable when a person takes the time to adjust the barrel, it been written many times how much powder and ball the native Americans would burn adjusting the barrel on their smooth bore bending the gun in a fork of a tree time it shot where it was pointed, most frontier folks new this. A buck and ball load didn’t hurt either, then you were ready for anything.

Having done Rev War reenacting for more decades than would seem mentally healthy, I have heard this topic come up many times. Here are some of the thoughts I usually contribute:

1) The .69 ball is the military load for a .75 caliber bore. It’s used so that the soldier can continue to load after several shots have built up residue in the tube. Since his shot is intended to be one of however many others in a volley, the fact that the ball comes out like a knuckle ball doesn’t really matter. Accuracy is not a major concern.

2) Increase the ball diameter–even just to .715–and accuracy and range go up considerably since there is far less blow-by and bouncing of the ball as it goes down the tube. A .735 ball is a world of difference.

III) For a .75-caliber Brit army musket in the 18th century, they made 30 to 40 cartridges out of a pound of powder. That’s 175-235 grains of powder per cartridge. I have yet to meet anyone who has fired live with that amount of powder. My point is that it is nearly impossible for us to recreate the precise firing conditions of the period. Their ballistics will probably be somewhat different.

D) A rate of fire of 3 per minute has been mentioned but, again, that is in a volley situation where everybody has to wait for the slowest soldiers. Washington issued orders that all recruits should be able to fire 15 rounds in 3 and 3/4 minutes–1 every 15 seconds. Good soldiers could improve on that and there are tricks that increase the rate even further. As has been noted, this is the positive side of the musket.

5) When it comes right down to it, what difference does accuracy make in the military? In the 18th century they used a regiment to send 3 or 400 rounds down field every few seconds. Today, everyone carries a fully automatic rifle. Do they take aim at a particular target? No. In my era–Vietnam–they had to modify the M-16 to fire only 3-round bursts ’cause the guys burned out barrels so quickly on full auto. Down through the ages it’s not take aim at an individual–it’s “spray and pray.”

Re: rifles–1) while rifles did some damage at Saratoga, the Brit light infantry dispersed Morgan’s men

2) many so-called “rifle companies” included men with smooth-bores

3) by mid-war, muskets had replaced rifles in the army

Mike – Thanks very much for your observations. Another factor besides ball size would be the barrel fouling. Velocity – when I shot over a chronograph – would rise dramatically after just a few shots. I can’t image loading with 175-235 grains of modern 2F (I don’t know if modern powder has the same power as that of the 1770’s – might be more, might be less). I have shot my Bess with 120 grains but being conservative I did not do more (it was quite dramatic!) and generally shoot only 100 grs. Keeping safe when using these, or any weapons, is rule #1. Always.

I don’t own a military smooth bore but do own several fusils,light muskets, in20 gage or about .62. With these I can shoot 2 inch groups at 25 yards and 41/2 inch at 50 yards. In this case its a .595 ball on top of wadding made of greased tow or unspun linen fibers and 80 grain charges of 2fg powder. My london fusil or north west trade gun has no sights at all. I have seen shootes out preform shot gun slug shooters at 50 yards with brown besses. The lack of accuracy ascribed to muskets was 1:a training issue as solders were taught to fire fast 2:smoke and confusion on a battle field. Remember while shooting at an officer or noncom on the battle field was ” not sporting” no such requirerment existed at sea. Musket shooting mariens could clear an enemy deck. Nelson was shot down while walking from a mast to 60 yards away also moving with the roll of the sea through the fog of powder smoke with a smooth bore musket.

Interesting stuff Jeff. I didn’t know that about Nelson, but there were definitely men who could shoot. I have a 77 Charleville and can be pretty accurate at 50 yards–especially the first shots like my first 5 here:

https://onedrive.live.com/redir?resid=AAF75B471FA65660!1183&authkey=!AOe1YmBNdNQsO2o&v=3&ithint=photo%2c.jpg

Now granted I have the advantage of modern powder, but that is about it.

For all the myth of poor performance of smooth bore muskets we should keep in mind that during the time of the revolution it took a company of shooters. about 70 shots to cause one hit to the enemy. During the Civil War rifled muskets needed to fire about 700 times to get a kill.It was said it took a mans wieght in lead to kill him. By veitnam it took about 7000 shots to put an enemy down. In terms of men involved in a battle looking at clasic smooth bore battle…Waterloo, a rifled musket battle…Gettysburg and the american sectors at D-Day with bolt action, simi auto and auto loading guns, the amount of hits was close to the same. Survival got better as med care got better. But those incapicitated by enemy fire remained close to the same.

It is interesting that the author seems to ignore historical arms and writings. For instance, the British military literature of the period does not call the post at the front of the barrel a “bayonet lug.” It is consistently refered to as a sight. Further, many historical long and short land pattern arms have a dovetail professionally cut into the tang, creating a rear sight. Then there are the numerous references to regiments practicing shooting at marks, often moving targets. The manual of arms instructs the soldier to purposefully sight down the barrel to ensure a good aim. Then there are the field tests of accuracy and ballistics conducted at places like Woolrich arsenal.

Modern testing using mass produced “replica” arms are not a good scientific study of the accuracy of 18th century British arms.

We did cover some of these very details in a subsequent article, Jason:

https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/08/the-aim-of-british-soldiers/

Thank you Don. I am glad to see the follow up.

Three observations. First, I agree with Mike that aiming was probably highly uncommon in 18th century battlefield situations. Given the amount of smoke that black powder generated, and the battlefield accounts I have read referring to participants only knowing where the enemy was by the barrel flashes that they could see through the smoke, I find it highly unlikely that much aiming was going on in most of these battles. There was at least one documented instance during the English Civil Wars where a rank of musket men took out a rank of their own unit standing almost directly in front of them! Second, one has to wonder about the rate of misfires, which must have been significant (even absent wet weather), something that was discussed a lot at the time but I am not aware of anyone doing any scientific evaluation of back then. Third, we have to keep in mind that soldiers at that time would have been considerably more disoriented by all of the noise, smoke, masses of men, and general confusion in a battle. This was an era when almost everyone lived on a farm, where 100 people gathered in one spot was a huge crowd, and machinery that made any kind of noise was minimal. A battle would have been a huge shock to the system, even for veterans; discipline (through drill) and maintaining a reasonable rate of fire were the keys to success, aiming would have been way, way down the list.

Regarding aiming, this from Col. Charles Scott to his men at Assunpink Creek at Trenton II as they waited for the Hessians to cross the bridge:

“Now I want to tell you one thing. You’re all in the habit of shooting too high. You waste your powder and lead, and I have cursed you about it a hundred times. Now I tell you what it is, nothing must be wasted, every crack must count. For that reason boys, whenever you see them fellows first begin to put their feet upon this bridge do you shin ’em. Take care now and fire low. Bring down your pieces, fire at their legs, and one man Wounded in the leg is better than a dead one for it takes two more to carry him off and there is three gone. Leg them dam ’em I say leg them.”

David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 305.

“I shoot it with a .69 inch roundball which weighs 476 grains, or one ounce,”

An ounce equals 437.5 grains, not 476 grains.

I shoot 20 bore fowlers. I generally shoot better scores with them than a rifle, and beat most of the rifle shooters on the course. It is a matter of training. It’s not the arrow, it’s the Indian.

I own and test shoot many infantry firearms from the 18th and 19th century—both percise reproductions and originals. Military firearms were very accurate and deadly for their time. It is all too easy with post-modern perceptions to look back into history with contempt and misunderstanding.

The Kings Short Land Pattern Musket (Brown Bess), was a second-rate weapon of the time. Its design follows the patterns of contemporary German states, being royalty of a Hanoverian house. Unfortunately, due to the almost indistinguishable myths surrounding our Revolution, it seems to be the default weapon for my fellow Americans when broaching the subject of early modern weapons.

French musketry was preeminent in quality and effectivness up until the mid 19th century. Their pattern 1776 (Americans were gifted old 1766 patterns) was fully machine made and interchangable. A milestone the British would not incorporate into their royal arms production until their 1853 pattern. French ammunition was also of much higher quality, given their long standing professional army. That is, their paper cartridges were of nitrated paper, and their lead balls lubricated with a mix of tallow and fat. This ensures the cartridge residue is fully burned in the bore, and softens fowling residue to facilitate reloading. This allowed their arms to maintain a much tighter windage in their arms (.69 barrels and .66 paper patched balls) and thus better accuracy. The British skipped all of these logistical concerns by using a .75 barrel with ~.69 bare ball, at the cost of accuracy.

Also the Brown Bess pattern of musket did have a front sight, which was also the bayonet lug. However, many long arms of the age had dedicated narrow front sights. A few even had rear sights.

The author’s discussion on cheek weld is deplorable in any age of firearms. Having a consistant cheek weld is important, but is easily achievable on all patterns and makes of musket of the age, let alone any modern firearms. As a combat veteran, I’ve hit many targets with “iron sights,” even if my cheek-stock placement was somewhat inconsistent. It is not the sole determining factor in aiming. And to avoid any red herrings of modern arms, I’ve replicated this with all my muskets on the range.

I give the author credit that he replicated the near correct load data for the “Brown Bess”, and defers to the marked difference between a flat target range, and the “two way range” of the battlefield. Yet tactical cohesion and effectiveness was of upmost concern in the profession of arms. This is why professional soldiers were drilled to perform actions as if by instinct. It allowed them to remain effective in the heat of action by defering to “muscle memory.” It is a concept that militaries still use in training recruits. Furthermore, keep in mind that the range of combat up until the late 19th centrury was quite close. Even modern infantrymen train for close combat in urban confines, and at ranges to 100 to 200 meters. It is the exception that terrain conditions or missions facilitate long-range small arms exchanges.

Thus a battalion of “regulars” could rapidly advance on a position while detachments would provide volley “covering fire.” After delivering their fire, they would chase or clear the enemy off the field with the bayonet. It was fast, ruthless, and efficient. Only with rare exception did it prove pyrrhic, such as at Breed’s Hill. And that has more to do with tactical foolishness than practice, as the British still took the positions but at heavy loss.

Comparing muskets with rifles of the day is akin to assault rifles to anti-material rifles of today. Rifles of the 18th century are heavy, unbalanced, clumsy affairs that are very slow to reload. Great for hunting, or a well planned ambush (that is, you have one good volley), but that is about it.

Thank you for this. I guess, when writing about hunting with a musket in the 17th century, one ought not use the idiom “have in one’s sights”!

The author is incorrect in saying that the Brown Bess (or the Charleville) muskets lacked sights. Actual armory-issued muskets had a slight grove cut in the breech end of the barrel almost opposite the frizzen pan. Also, the bayonet lug was intentionally place on the top of the barrel to serve as a sight. While wildly inaccurate, these were sights. British manuals of the day also specified how to aim the musket (The Manual Exercise, As Ordered by His Majesty, in 1764). Aiming at this prior of time was called “presenting”. These manuals were reprinted in America in the 1770s and probably used by many militia units. The Charleville used during the Revolutionary War had a dedicated front sight and the bayonet lug was placed on the underside of the barrel.

We did cover these details in a subsequent article:

https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/08/the-aim-of-british-soldiers/