Continued from yesterday. Click here to read part 1.

When British attack upon Philadelphia threatened in 1776, Nicola was appointed Town Major for the city. In this assignment, he was responsible for the city guards, protection of Continental Army stores and property in the town, and establishment and maintenance of barracks and billets for all units moving through or garrisoned within Philadelphia. This was a role that Nicola was highly experienced with from his thirteen years of similar service in Ireland, and he proved quite effective in this position for the next two years. Nicola continued to support the Continental Army in various ways, to include preparing a “General Register of the Officers of the American Army for 1779” the first comprehensive listing of every officer then serving the United States, essentially a Continental Army equivalent to the British Army Lists that were published annually.[xiv]

While managing the garrison of Philadelphia, Nicola devised a scheme directly derived from the British Army approach of using retired or infirm soldiers to provide garrisons of established posts, thus freeing up able bodied soldiers for field service: “The invalids in the British forces consist of soldiers partly disabled by wounds and veterans, who from old age and length of service are rendered incapable of the duties of an active campaign, but are still judged fit for garrison duty.”[xv] Designated as the Invalid Regiment of the Continental Army, this regiment was formally organized by the Continental Congress on June 20, 1777, with Nicola as Colonel.[xvi]

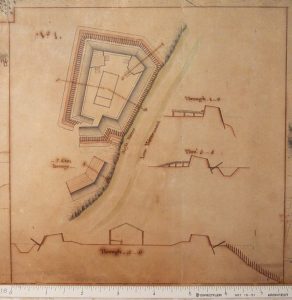

The Invalid Regiment originally served in Philadelphia under Nicola’s tutelage. When the city was evacuated upon the British advance in the fall of 1777, it ended up spending the winter of 1777-1778 safeguarding Continental Army storehouses in eastern Pennsylvania, with Nicola making his headquarters in Easton.[xvii] Upon the British evacuation of Philadelphia, Nicola’s Invalids returned to Philadelphia. Nicola prepared the only known cartography of the British defenses of that city. Nicola and his invalids remained in Philadelphia until ordered to support the defense of the Hudson Valley in the summer of 1781.

In 1779 Nicola and the other members of the American Philosophical Society, which had lapsed in 1774 at the onset of the Revolution, determined to resurrect the organization. At a meeting in Philadelphia on March 5, 1779, at which Nicola was present, it was “unanimously agreed that the Meetings and business of the Society be revived.” Shortly thereafter, on March 19th Nicola was elected one of the three curators of the society. Nicola continued active in the organization, and regularly attended meetings between then and 1785, serving as one of three curators throughout the entirety of that period. Although clearly occupied with his command responsibilities over the Invalid Regiment, he continued to present papers to the society. On May 20, 1779 he read his essay “To Account for the Deluge from the Suspension of the Diurnal Rotation of the Earth.” He continued his contributions on February 19, 1781 when he submitted a “Plan for a Rain Gauge” to permit accurate daily measurements of rain. On March 5, 1784 he presented “Observations on Petrified Bones Found Near the Ohio [River]- thigh bone, tusk and grinder, brought to the City by Major Craig.”[xviii]

The Invalid Regiment arrived at the Fishkill Supply Depot, a major Continental Army logistical facility located approximately fifteen miles northeast of West Point. The Invalids were transferred there to relieve marching regiments of the Continental army from guard duty at the depot, in support of Washington’s forthcoming operations against first New York City, and ultimately against Yorktown. As they had at Philadelphia, Nicola and his regiment provided good service to their nation at Fishkill, and they freed up valuable and scarce manpower for Washington to carry south with him, while at the same time preventing a British incursion in response from New York City up the Hudson.[xix]

As the Revolution wound down, the financial situation of the Continental Congress, always tenuous at best, collapsed. Payments to the Continental Army were in serious arrears, and both Nicola and the officers and men that he was responsible for were in desperate financial straits. Shortages of clothing and food were endemic. In this circumstance, Nicola wrote to George Washington on May 22, 1782, concerned that “this gives us a dismal situation for the time to come.” Noting that “from several conversations I have had with officers & some I have overheard among soldiers, I believe it is generally intended not to separate after the peace ‘til all grievances are redressed, engagements & promises fulfilled.” Nicola then went on to suggest the formation of a separate state on the frontier formed from discharged solders of the Continental Army. Alarmingly, Nicola recommended this be established as a separate state with its own constitution, and a supreme executive authority with “some title apparently more moderate than king.” Needless to say, Washington was stunned and concerned at this suggestion, quickly repudiated any interest in such a scheme, and counseled Nicola in unmistakable language to “never communicate, as from yourself, or any one else, a sentiment of the like nature.” Obviously, if the American people or the Continental Congress believed that the Continental Army intended to establish its own state under its own government and executive authority, the results would be devastating to the new republic. Nicola wrote two apologetic letters to Washington, and in short order the matter was dropped. Nicola’s concept never passed beyond himself and Washington (exempting, of course, Washington’s trusted aides). [xx] Washington and Nicola regularly corresponded throughout 1782 and 1783, and Washington continued to value Nicola’s leadership and the services of the Regiment of Invalids.[xxi]

Washington could easily censor Nicola, but he could not as readily resolve the growing dissension and displeasure swelling amongst the soldiers and officers of the Continental Army. Ten months later, the Newburgh Conspiracy would be the result. Nicola anticipated the growing level of dissent in the army by almost a year, and offered Washington an admittedly ill-conceived suggestion to address it.[xxii] And unfortunately for Nicola’s reputation, he is now best remembered as the Continental Army officer who offered a King’s Crown to George Washington in a nefarious scheme to usurp democracy, although he did no such thing.

The Invalid Regiment was disbanded at the end of the war in late 1783, concluding its service garrisoning Constitution Island across the Hudson River from West Point. The Continental Congress recognized Nicola’s eight years of committed service to the Continental Army by appointing him a Brigadier General at the very end of the war, a ceremonial promotion as he never served in this position. Following the war, Nicola continued to serve as Barracks Master to the U.S. Army in Philadelphia, a position with little real responsibilities that was more of a sinecure to the distinguished and senior veteran. Nevertheless, with the outbreak of the whiskey rebellion in 1794, Nicola again found himself with heavy responsibilities for supporting and sustaining the militia army that Washington marched to Western Pennsylvania to suppress the unhappy taxpayers. Nicola remained active in the American Philosophical Society and Society of the Cincinnati, and later in his life espoused Unitarian religious doctrine. He was also a Mason.[xxiii]

Nicola’s health began to deteriorate in the later years of his life, and in 1798 he moved to Alexandria, Virginia to be close to his daughter. His health deteriorated to the point that he was obliged to request financial support from the Society of Cincinnati, writing about “My very ill state of health, owing to the very debilitated state of my stomach, for which I am debarred the use of all fruits [and] vegetables, potatoes excepted, prescribed generous liquors and warmest spices.”[xxiv] He died in Alexandria in 1807, at the advanced and distinguished age of 90, nearly destitute. The Society of Cincinnati paid for his funeral arrangements.

Colonel Lewis Nicola’s service to his adopted nation was significant, as not only a member of the Continental Army, but as a founding and active member of the American Philosophical Society. Although 59 years old in 1776, he still served for eight years with the Continental Army, translated two important military treatises for its use, created a new system of military drill and exercises, and formulated the creation of an Invalid Regiment that not only afforded salaried employment to disabled and maimed veterans of the Continental Army, but helped augment Washington’s always scarce manpower. At the same time, he had been in the forefront of scientific study and scholarship of the new nation, contributed numerous research papers, and having the great distinction of being the very first American to establish a journal devoted to scientific, philosophical and scholarly study and dissemination. Colonel Lewis Nicola is fully deserving of his nation’s thanks and appreciation, and should be remembered for far more than a single poorly considered letter.

Notes

The author wishes to acknowledge the generous assistance of Mrs. Kathy Ludwig of the David Library of the American Revolution, Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania; Mr. Roy E. Goodman, Curator of Printed Materials, Library, American Philosophical Society; Ms. Glenys A. Waldman, Librarian, The Masonic Library and Museum of Pennsylvania; and Ms. Valerie Sallis, Archivist and Mrs. Ellen McCallister Clark, Library Director, Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, D.C. with the research for this article.

[xiv] Lewis Nicola, “The General Register of The Officers of the Continental Army for 1779” Society of Cincinnati Library, Washington D.C.

[xv] Edward E. Curtis, The Organization of the British Army in the American Revolution (1926; reprint edition Gansevoort, New York: Corner House Historical Publications, 1998), 2n.

[xvi] The author’s patriot ancestor, Ensign William Russell of the 3rd Pennsylvania Line, was accepted for duty in the Invalid Regiment following his serious wound with loss of a leg at the Battle of Brandywine, but never joined the regiment due to the severity of his injury.

[xvii] Howard R. Marraro, “Unpublished Letters of Colonel Nicola, Revolutionary Soldier” Pennsylvania History 13:4 (October 1946), 276; and Washington to Nicola, April 14, 1778 in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources (1931-1944), http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WasFi11.xml&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=243&division=div1, accessed 1 February 2012.

[xviii] Early Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1744-1838 (Philadelphia: McCalla & Stavely, 1884), 100, 101, 103, 107, 108, 110, 114, 121, 123, 125, 129; and Lewis Nicola, “Plan of a Rain Gauge” American Philosophical Society, Manuscript (February 19, 1781).

[xix] John C. Fitzpatrick, The Spirit of the Revolution (1924; reprint edition Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press, 1970), 179-189.

[xx] This episode has been comprehensively and exhaustively assessed by Robert F. Haggard, “The Nicola Affair: Lewis Nicola, George Washington, and American Military Discontent during the Revolutionary War” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 146:2 (June 2002), 139-169.

[xxi] Nicola and either Washington or his staff officers subsequently corresponded on at least seventeen different occasions in 1782 and 1783. George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/gwhtml/gwhome.html, accessed 2 February 2012.

[xxii] William M. Fowler, Jr., “Draft of Speech Delivered at Mount Vernon, July 20, 2006” (Department of History, Northeastern University, August 15, 2006), http://iris.lib.neu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=fowler_speech_pub, accessed 1 February 2012.

5 Comments

Sir,

Thank you for your article on Lt. Col. Nicola.

Yes, thank you very much, Douglas. This was my first time learning about Nicola. Very interesting and well researched.

Really interesting remarks on the Invalid regiment. They were subjects of a recent discussion I remember on a message board. Thanks for the insight.

This was quite informative and covered a lot of ground that I did not know. Thank you for adding to my knowledge base. This shows just how important it is to place primary sources within the context they were written. It is quite obvious that if Washington continued to correspond with Nicola that Washington did not let the matter drive a wedge between them. The idea may not have been Nicola’s originally and could have been extrapolated from the disgruntled officers Nicola had spoken with over time. Interesting thought on setting up another country in the interior though.

The only thing I didn’t like about the article was the jumping around in dates. It was distracting.