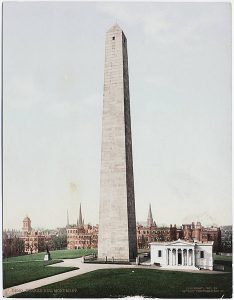

Yesterday marked the 170th anniversary of the commemoration of the Bunker Hill Monument. It took the Bunker Hill Monument Association, thousands of individual donors, a craft and bake sale organized by Sarah Josepha Hale, a large donation from philanthropist Judah Touro, and seventeen years to complete construction of the 221-foot tall obelisk, the first major monument to honor a battle of the War for Independence. Although a long and expensive undertaking, the idea for the monument would not have come about had it not been for the political ambition of Henry Dearborn.[1]

In 1818 Dearborn ran for governor of Massachusetts. He faced incumbent John Brooks. As a Republican in a predominantly Federalist state, Dearborn needed all the positive press he could muster to strengthen his campaign.[2] So when the editor of the Philadelphia-based publication Port Folio, Charles Miner, approached Dearborn about verifying and editing a British soldier’s map depicting the Battle of Bunker Hill, Dearborn jumped at the opportunity.[3]

Dearborn hoped to accomplish two goals by editing and verifying Miner’s map. First, he viewed the map as an opportunity to add to his Revolutionary War Journals, which Miner had published. Dearborn had served in the New Hampshire militia and Continental Army from Bunker Hill to Yorktown, but he started logging his experiences after Bunker Hill. Second, Dearborn hoped to generate political support by highlighting his service to both Massachusetts and the United States.

Dearborn submitted his edited version of the map to Miner along with a fourteen-page account of the battle. In March 1818, Miner published Dearborn’s map and battle description. Dearborn’s most surprising and controversial recollection was: “[General Israel Putnam] remained at or near the top of Bunker Hill until the retreat…he not only continued at that distance himself during the whole action, but had a force with him nearly as large as that engaged. No reinforcement of men or ammunition was sent to our assistance.”[4] According to Henry Dearborn, New England’s beloved “Old Put,” hero of the French and Indian War and gallant patriot, was a coward.[5]

Dearborn’s claims did not sit well with the voters of Massachusetts or with New Englanders in general. Dearborn committed a grave error in his bid for positive press coverage: he assaulted the honor of a dead man; Israel Putnam had died in May 1790. Dearborn lost the election and a contentious debate over Putnam’s conduct carried on in the New England and New York press for more than twenty years.[6]

At the heart of the dispute lay Putnam’s whereabouts and actions during the heat of the battle. Did Putnam stand on Bunker Hill fruitlessly trying to get a large group of men to build entrenchments while the battle raged on Breed’s Hill? Or did he pace the Breed’s Hill battle lines encouraging his men to strengthen key points along the rail-fence and breastwork and not to fire until he gave the order?

Partisans of Putnam, Dearborn, and unaligned veterans submitted their battle accounts to newspapers, pamphlet publishers, and historians. Putnam’s son Daniel and Thomas Grosvenor submitted the first replies to Dearborn’s accusations. Daniel decried Dearborn’s claims of cowardice. His father had been a brave man. During the “great peril and hardship, from 1755-1763, ‘He [Putnam] dared to lead where any dared to follow.’” Grosvenor bolstered Daniel’s claim of his father’s heroism by offering his account of the battle: “General Putnam during the [battle] was extremely active, and directed principally the operations…a detachment of four lieutenants (of which I was one) and one hundred and twenty men…were by the general ordered to take post at a rail-fence on the left of the breast-work, and extended our left nearly to Mystic river…Of the officers on the ground, the most active within my observation were Gen. Putnam, Col. Prescott, and Capt. Knowlton.”[7] Putnam and Grosvenor’s defense did little to stop the speculation and rumors of the accuracy of Dearborn’s account.

John Trumbull added to the ferment. Afraid that the controversy might invite criticism of his artwork, Trumbull wrote a letter to Daniel Putnam to explain his placement of Israel Putnam in his painting memorializing the Battle of Bunker Hill.[8] Trumbull related how he had met Colonel John Small, a soldier in the British Army and veteran of Bunker Hill, during his stay in London in the summer of 1786. Small had served with Putnam during the French and Indian War and opposed him at Bunker Hill. Trumbull showed him his The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775. Small remarked: “I do not like the situation in which you have placed my old friend Putnam; you have not done him justice.” According to Small, Putnam had occupied a central place in the battle. In fact, Small related how he saw “several young men leveling their pieces at me; I knew their excellence as marksmen, and considered myself gone. At that moment my old friend Putnam rushed forward and striking up the muzzels of their pieces with his sword, cried out—‘For God’s sake, my lads, don’t fire at that man—I love him as I do my brother.’”[9] Small’s testimony turned the debate over Putnam’s actions into a full-blown controversy. However, the dispute no longer centered on Putnam’s character, but on how Joseph Warren died.

In further defense of the accuracy of his painting, Trumbull offered Small’s account of Joseph Warren’s death. Small related: “Gen. Howe…called to me: ‘Do you see that elegant young man who has just fallen? Do you know him?’ I looked to the spot towards which he pointed—‘Good God, sir, I believe it is my friend Warren.’ ‘Leave me then instantly—run—keep off the troops, save him if possible.’ I flew to the spot: ‘My dear friend,’ I said to him, ‘I hope you are not badly hurt;’ he looked up, seemed to recollect me, smiled, and died!”[10] Many battle veterans took issue with Small’s account of Putnam’s bravery, but his recollections of Joseph Warren’s death drove them to pick up pen and paper to set matters straight.

In June 1818, Abel Parker of Jaffrey, New Hampshire, a veteran of Colonel William Prescott’s unit, corroborated Dearborn’s account: “I have never seen any account which I considered in any degree correct, until the one published by General Dearborn.” Parker demurred from vindicating Dearborn’s statement earlier because he felt that Putnam’s supporters had failed to bring “forward any evidence to disprove the general’s statement.” However, Parker felt compelled to relate his account of the battle only after he had read the “letter from Col. Trumbull to Col. Putnam, wherein mention is made of a conversation with Col. Small in London, I concluded…that to remain any longer silent, would be absolutely criminal.”[11]

Likewise Samuel Lawrence of Groton, Massachusetts, also felt obliged to correct Small’s portrayal of Putnam’s actions and Warren’s death. One of Prescott’s officers, Lawrence related that “Gen. Putnam was not present either while the works were erecting, or during the battle. I could distinctly see the rail fence and the troops stationed there during the battle, but Gen. Putnam was not present as I saw.” With regards to Warren’s death, Lawrence stated “I saw Gen. Warren Shot; I saw him when the ball struck him, and from that time until he expired. No British officer was within forty or fifty rods of him, from the time the ball struck him until I saw he was dead.”[12]

Michael McClary of Col. John Stark’s regiment also defended Dearborn’s account: “I was in the battle from its commencement to the end, and have no recollection of seeing Gen. Putnam in the battle, or near it…on our retreat from Breed’s Hill, in ascending Bunker’s Hill, and arriving on its summit, I well remember of seeing Gen. Putnam here, on his horse, with an Iron spade in his hand, which was the last I saw of him on that day.”[13]

Dearborn’s account of the battle played a large role in his electoral defeat. However, it also served as a catalyst for historical memory. Dearborn’s recollections prompted people to think about and remember the Battle of Bunker Hill. Inspired by the accounts of the battle and the heroism of the men who fought in it, leading citizens of Boston and New England formed the Bunker Hill Monument Association in 1823. The purpose of the Monument Association was to create a lasting memorial in honor of Joseph Warren and the brave men who fought alongside him. The organization agreed that such a commemoration called for the construction of a 221-foot granite obelisk on the top of Breed’s Hill.[14]

On June 17, 1825, Americans from all over the nation commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill by gathering on Breed’s Hill. Festivities included the monument cornerstone laying ceremony and a spirited oration by Daniel Webster. One hundred and seventy years later, the Bunker Hill Monument still occupies a conspicuous place in the Boston skyline. It continues to stand as a lasting memorial to the battle, fulfilling the hopes of the Bunker Hill Monument Association and the thousands of Americans who donated money towards its construction.

[1] Henry Dearborn had a long military and political career. In addition to his Revolutionary War service, Dearborn commanded the United States Army during the War of 1812. As a politician, Dearborn served as the United States Marshall in the Maine Territory under President George Washington and as Secretary of War under Thomas Jefferson. Between 1793 and 1797, Dearborn represented Massachusetts in Congress.

[2] Although the Hartford Convention of 1814 proved the ruin of the Federalist Party, it took Federalist strongholds like Massachusetts years to phase out the party.

[3] Jacob Cist of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania found the battle map in his family papers in 1818. Henry de Bernier drew the map at some point during his service in the Tenth Infantry unit of the Royal Army. Cist sent the map to Miner for publication. Henry Dearborn, “An Account of the Battle of Bunker Hill,” Written for the “Port Folio” at the request of the Editor, (Philadelphia: 1818).

[4] Henry Dearborn, “An Account of the Battle of Bunker Hill,” 13-14; H. Dearborn, “From the Port Folio of March 1818: An Account of the Battle of Bunker Hill.,” Newburyport Herald, Published as Newburyport Herald, April 21, 1818; H. Dearborn, “On the 17th of June 1775,” Essex Register, April 22, 1818; H. Dearborn, “From the Port Folio for March Last. Gen. Dearborn’s Account of the Battle of Bunker-Hill,” Boston Patriot & Daily Chronicle, April 24, 1818.

[5] Israel Putnam served in the British Army during the French and Indian War. A member of Robert Rogers’ Rangers, Putnam fought at the Battle of Ticonderoga in 1758.

[6] For more information on honorable political and newspaper practices in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries see Joanne Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 105-158.

[7] In his letter to Dearborn, Putnam included a June 1783 letter from George Washington to his father congratulating Israel Putnam on his courage and valor. Daniel Putnam, A letter to Major-General Dearborn, Repelling His Unprovoked Attack on the Character of the Late Major-General Putnam; and Containing Some Anecdotes to the Battle of Bunker-Hill Not Generally Known, (Boston: Munroe and Francis, 1818), 2, 6-7; “Port Folio H. Dearborn, Gen. Putnam,” Columbian, Published as The New-York Columbian, May 14, 1818; Daniel Putnam, “A Letter to Major Gen. Dearborn, Repelling His Unprovoked Attack on the Character of the Late Major Gen. Putnam,” New-York Daily Advertiser, May 22, 1818.

[8] Daniel Putnam sent John Trumbull’s letter to the newspapers as additional evidence of his father’s bravery.

[9] John Trumbull, “Dearborn Vs. Putnam,” Essex Patriot, May 23, 1818. Letter also appears in John Fellows, The Veil Removed; or Reflections on David Humphreys’ Essay on the Life of Israel Putnam (New York: James D. Lockwood, 1843), 111-112.

[10] John Trumbull, “Dearborn Vs. Putnam,” Essex Patriot, May 23, 1818. Letter also appears in John Fellows, The Veil Removed; or Reflections on David Humphreys’ Essay on the Life of Israel Putnam, 111-112.

[12] John Fellows, The Veil Removed; or Reflections on David Humphreys’ Essay on the Life of Israel Putnam, 115-116.

4 Comments

Very interesting article. I didn’t know any of this. Henry Dearborn of course participated in the march to Quebec. Left a great diary (if I remember correctly when his men were starving they ate his dog).

There is a lot in here I didn’t know. Basically, all of it! Thank you.

In addition to the two reasons you cite, could Dearborn also have been looking to restore his reputation in light of his poor leadership during the War of 1812? He oversaw the 1812 and 1813 Canadian campaigns, but was pushed out in mid-1813 after botching the 1813 Niagara campaign (snatching defeat from the jaws of victory over the course of a month. Would have been recent memory in 1818.

Trivia: while the Bunker Hill monument began first, and is larger, the very similar (but lesser known, I think) Groton Monument began just a year later and was finished a just 4 years: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groton_Monument. Better contractors? 🙂

Phil, thank you for raising the point about Dearborn’s service in the War of 1812. His failure in Canada played a role in why he wanted to highlight his service in the War for Independence. Dearborn’s journals provide a great glimpse into the war as he served in all of the major northern campaigns and Yorktown. I am not sure how he accomplished it, but Dearborn witnessed nearly every important moment of the war.

Also, thank you for the trivia on the Groton Monument.

What a fascinating account … I do wonder about the two contemporary accounts of Dr. Warren’s death. If the skull that is reputed to be his, actually *was* his, the spot at which the musketball entered his cheek would have meant an immediate death — I don’t know if Small’s account can be believed (that Warren recognized him and smiled) and Lawrence’s account also seems to suggest that Warren’s death wasn’t as immediate as the wound in the skull would indicate. So where is the truth? Were these contemporary accounts somehow erroneous or exaggerated? Or is it possible that the skull that was believed to be Warren’s, actually was not? Food for thought…