September 8, 1781

Francis Marion is best known for his leadership in the partisan war of 1780-1781, during which he and his volunteer militia harassed British troops and the Loyalist militia in South Carolina, first disrupting the British occupation of the state and later helping to clear royal forces from a considerable area. Once this task had been accomplished, Marion faced a new challenge: commanding his militia in a set piece battle alongside other militia and Continental troops under Major General Nathanael Greene. Despite his lack of experience in such circumstances, Marion put his earlier experience as a Continental officer to good use and led his men effectively at the Battle of Eutaw Springs on September 8, 1781, in the last major open field battle of the War for Independence.

Marion’s military experience began in 1761, when he was about nineteen years old. Enlisting for service in the Cherokee War, Marion enlisted in the South Carolina militia and was commissioned first lieutenant in a company commanded by another South Carolinian who would rise to prominence in the Revolution, William Moultrie. As part of British general James Grant’s expedition, Marion participated in only one battle but distinguished himself for his courage under fire.

In June 1775 Marion returned to military service when South Carolina began organizing troops in response to the outbreak of fighting at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. He was commissioned a captain in the state’s 2nd Regiment of infantry, again serving under Moultrie, who was the regiment’s colonel. Marion was promoted to major in February 1776 and on June 28, while assigned to the garrison of Fort Moultrie, took part in the successful defense of Charleston against a British attack. In September the Continental Congress assumed control of South Carolina’s regular regiments, and Marion’s unit became the 2nd South Carolina Continental regiment. He continued to serve as a regular officer, earning promotion to lieutenant colonel, until the British capture of Charleston in May 1780. Shortly afterward, Marion embarked on his well known career as a partisan leader.

Beginning in April 1781, Marion conducted joint operations with a force of Continental troops that Greene had dispatched to assist him in a campaign against British posts. The Continentals were the Legion of Lieutenant Colonel Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, and the two leaders cooperated successfully. Marion, now a brigadier general of militia, and Lee were both strict disciplinarians, skilled at the type of partisan war they had to conduct, and innovative. Their smooth cooperation demonstrated Greene’s ability to utilize his subordinates to maximum effect. Before dispatching Lee to join Marion, Greene had briefly considered reinforcing Sumter with the Legion instead, but had decided that Lee and the prickly Sumter would be unlikely to get along. Greene’s judgment was validated when Marion and Lee forced British Fort Watson on the Santee River to surrender and then went on to capture Fort Motte. Their success cut the British supply line to Charleston and forced the British to evacuate Camden. Lee and Andrew Pickens captured Augusta, Georgia, while Greene’s siege at Ninety Six failed, but the British were forced to abandon the now isolated post. The Americans had regained control of the southern backcountry.

Greene camped his army at the High Hills of Santee, leaving Marion and Lee, operating separately, to watch the British forces in the vicinity of Charleston. Meanwhile, a British force that Lee estimated at 1600 men began probing deeper into the interior of South Carolina, marching along the south bank of the Santee to the south side of the Congaree River. Lee urged Greene to attack the isolated force, which was commanded by an officer newly arrived in South Carolina, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Stewart. Marion was watching a second British detachment of about 600 men that was at Eutaw Springs in mid-August.

Considering Lee’s advice, Greene observed on August 14 that Stewart had provided him “so good an opportunity … of giving the enemy a deadly blow.” While he was willing to risk attacking Stewart with only his Continentals if necessary, Greene worried that even a victory would result in heavy casualties, and a defeat might prove disastrous. “Six or eight hundred Militia would make the business easy and success certain,” he told Lee.

Greene marched from the High Hills on August 23 after issuing orders to his detachments and various militia units to unite with the main army. However, he did not send Marion instructions at this point, perhaps because Marion was already closer to the British than other American units. He had in fact been extremely active during the last week of August, shadowing and skirmishing with British detachments between the Combahee and Edisto rivers. After bloodying various groups of British, Hessians, and Loyalists, Marion fell back to Round O, left that place on the night of September 1 and marched forty-two miles toward Eutaw Springs, where he found Stewart’s force and informed Greene.

Upon learning of Marion’s activities and location, Greene replied with lavish praise. He then informed Marion of his plan to attack the British, and asked him “to form a junction with us as soon as possible,” but to do so by remaining near the British rather than marching toward the main army. On September 6, Marion informed Greene that he had received the instructions. At the time, he had been camped twenty miles below Eutaw Springs, and he promptly ordered a night march since he had to “go round the Enemy.” He had reached Henry Laurens’s plantation and would stay there and await orders, as his men and horses were “Greatly fatigued.” Greene and the rest of the army joined Marion there the next day, and together they marched to Burdell’s Tavern on September 7. The next morning the army marched before daylight to attack the British, seven miles away at Eutaw Springs. Stewart was unaware of the Americans’ presence, and Greene hoped to take the British by surprise.

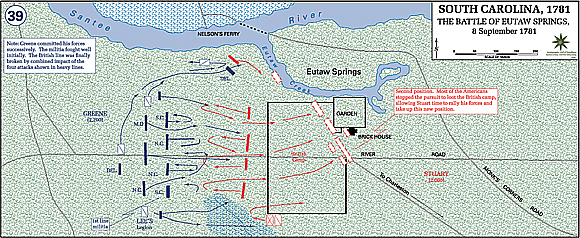

Greene arranged his army’s marching order according to each unit’s intended position in the line of battle to be formed before attacking. Lee’s Legion was in front, followed by Lieutenant Colonel William Henderson’s South Carolina state troops and the South Carolina militia commanded by Marion and Andrew Pickens, and the Marquis de Malmedy’s North Carolina militia. The Continentals followed. Unfortunately, two American deserters cost Greene the element of surprise. Arriving at Stewart’s camp in the early morning, they informed him that Greene was approaching. Skeptical, Stewart dispatched Major John Coffin with some dragoons and light infantry to scout the road to Burdell’s. Four miles from the British camp Coffin saw the approaching Americans and rashly charged. Coffin was repulsed and hurried back to inform Stewart of the Americans’ approach.

While Stewart formed his troops for battle, the Americans deployed opposite the British. Using the system that Daniel Morgan had so successfully employed at Cowpens, Greene formed his army in two lines with the militia in front. On the left or northern end of the American first line were Henderson’s state troops, then Pickens’s South Carolina militia, Malmedy’s North Carolinians, Marion with an estimated 240 men, and Lee’s Legion anchoring the right of the line. At about 9 a.m., Greene ordered his first line to attack, and Marion’s troops surged forward with their comrades.

The militia advanced until they came under fire, then halted and exchanged volleys with the British. One of Marion’s soldiers wrote that the brigade’s marksmen “fired with great precision, galling the enemy greatly.” The North Carolinians to their left did not perform so well. After firing only three or four rounds, they began to fall back, leaving Marion’s left flank exposed. Fortunately, Greene reacted quickly and hurried the two North Carolina Continental regiments forward to fill the gap in the line. Altogether, Marion’s troops fired seventeen rounds while holding firm less than a hundred yards from the British line. This appears to be much more than Greene had expected – one of Marion’s soldiers, William Vaughan, claimed that Greene had ordered Marion to fire only twelve rounds before retiring. Vaughan recalled that after firing the first twelve rounds, Marion’s brigade marched to the right at an oblique angle and then renewed their fire on the British flank. This movement may have been due to the necessity of making space in the line when the more numerous North Carolina Continentals replaced that state’s fleeing militia.

The toe-to-toe struggle took its toll on Marion’s brigade. Both the heat and the enemy fire were intense. John Painter, one of Marions’s troops, noted later that “the day was excessively hot.” Enemy fire took its toll. Jehu Kolb was wounded by a musket ball in his left knee. Jim Capers, a free black who had served under Marion as a drum major when the latter was a Continental officer, was acting in the same capacity at Eutaw Springs and wounded four times: two cuts on his face, a sword cut to the head, and was shot through the body, the ball passing completely through Capers and killing a drummer, Paul Ram Lee, who was standing behind him. James Delaney, a cook who had exchanged his ladle for a musket, was also wounded. Even those who escaped injury commented on the fierceness of the fighting. Benjamin Thomson said it was the “most severely fought battle” he had ever taken part in. Henry Goodman agreed, calling the engagement the “hottest of battles.”

As a result of Marion’s steady leadership and his soldiers’ courage, the brigade, although unable to advance, held its ground until the North Carolina Continentals broke, again exposing Marion’s left. This time the British, sensing victory and without orders, launched a spontaneous bayonet charge that forced Marion to order a retreat. One of his troops, Thomas McDow, noted that “a charge of Bayonets was made against them when they gave way for the regulars.” The charging British overtook some of Marion’s men as they were withdrawing. It was probably at this time that Capers suffered the wound from a sword blow, while James McMillan was wounded in the thigh by a British bayonet. Nevertheless, few if any of Marion’s soldiers were captured by the British counterattack. The British had other worries. Greene, with the same impeccable sense of timing that he had shown in committing the North Carolina Continentals to replace the militia, had ordered the Virginia and Maryland Continentals to charge as soon as he saw the front line begin to give way. The Continentals advanced, Marion shifting his retreating brigade to the right of the Virginians to allow them clear passage.

Marion reformed his brigade while the Continentals drove back the British. Later in the day, when the American advance became bogged down in the British camp and in front of the brick house and blackjack thicket on the British right, Greene summoned Marion to make a final effort to dislodge the British before the rest of Stewart’s force could regroup. Unfortunately, Marion and his troops were no more able than the Maryland and Virginia Continentals to surmount these obstacles, and withdrew when, after four hours of heavy fighting, Greene ordered his army to fall back to Burdell’s in the face of a British attack.

Back at camp, the officers tallied their losses. Several different “official” reports of American casualties were compiled. According to one recorded by Captain Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware Continentals, the total losses suffered by the South Carolina militia were two killed and 27 wounded. The total included both Marion’s brigade and that of Andrew Pickens, the latter having numbered over three hundred men when it went into battle. It is not clear whether these figures also included the many South Carolina militiamen who were assigned to Lee’s Legion and Lieutenant Colonel William Washington’s regiment of Continental Light Dragoons to strengthen those units.

The casualties understate the actual losses suffered by the South Carolina militia. The North Carolina militia, numbering only two hundred men and engaged for only one-third as long as Marion’s and Pickens’s brigades, was recorded as having lost 6 killed, 31 wounded, and 8 missing. Given the additional time that Marion’s brigade was engaged, not including its return to action later in the battle, and its greater strength of 240 men, Marion’s losses may have been three times higher than those of the North Carolinians. Henry Lee later insisted that Greene had underreported his losses, and the work done recently by Lawrence E. Babits on the Battle of Cowpens proved that this was true of that engagement, and that American losses were far higher than reported, strengthens Lee’s assertion. Whatever Marion’s actual casualties may have been, his brigade performed admirably in its contest with veteran British and Loyalist troops, and retained its organization after being forced from the field, so that it was able to return to action later. Marion and his brigade distinguished themselves that day.

Greene recognized that fact and was effusive in his praise. In general orders issued the day after the battle, he noted that the militia “answered his most sanguine Expectations,” a compliment he generously extended to Malmedy’s North Carolinians as well as the troops of Marion and Pickens. In a separate letter to South Carolina governor John Rutledge, Greene remarked that the militia “did honor to that class of Soldiers.” In a similar vein, he informed Thomas McKean, president of the Continental Congress, on September 11 that “General Marion, Colonel Malmady and General Pickens conducted the Troops with great gallantry and good conduct, and the Militia fought with a degree of spirit and firmness that reflects the highest honor upon this class of Soldiers.” Rutledge also applauded the performance of Marion and Pickens. “That distrust of their own immediate commanders which militia are too apt to be affected with, never produced an emotion where Marion and Pickens commanded,” the governor wrote.

Marion’s comments were characteristically brief. “My Brigade behaved well,” he told his friend Colonel Peter Horry. In any case, Marion did not have time either to count casualties or write lengthy reports. In the early morning hours of September 9, Greene dispatched Marion’s brigade and Lee’s Legion to swing past Stewart’s left flank and try to prevent Major Archibald McArthur’s detachment of 400 British troops from reinforcing Stewart. Although Marion and Lee skirmished with McArthur’s troops and captured 24 British soldiers and 4 Loyalists, they were too weak to stop McArthur from uniting with Stewart. It made no difference, since on the night of September 9 Stewart retreated toward Charleston. The British threat to the interior of South Carolina had been ended.

Marion had played a key role in Greene’s strategic victory at Eutaw Springs. Many officers with experience as partisans had difficulty working with Continental officers, as Thomas Sumter had already demonstrated, and the militia had frequently proven unreliable in set piece battles, such as that fought at Camden just over a year earlier. Marion, however, was different. His experience as a Continental officer and later cooperation with Lee’s Legion enabled him to serve effectively with and under Continental officers. Marion’s strict discipline, insistence upon adequately training his militiamen, and the example of his visible courage under fire kept his troops in the field even after the North Carolina militia, and Continentals, broke under enemy pressure. Greene, like his mentor George Washington, always harbored distrust for the militia, but Marion earned his confidence. The reward was more hard service alongside Lee after the battle, but in choosing officers and troops to carry out a difficult and risky task, the fact that Greene turned to Marion and his militia to operate with Lee showed that Marion had convinced Greene of his own merit and that of his men.

4 Comments

Good morning Jim, a fine subject indeed. I really enjoyed it. I am always excited to see references to Coffin’s Dragoons. Chosen from the strongest and best of the New York Volunteers, I believe Coffin’s troop should be recognized by history as Francis Marion’s chief nemesis. While Tarleton is credited with the Swamp Fox nickname, I only know of one episode of him chasing Marion about South Carolina. On the other hand, Coffin and his dragoons spent months on duty between Charleston and the outposts. Hoping to fnd time to write that relationship up one day. 🙂

Anyway, I brought it up to point out that Coffin was not only the first British regiment to raise the alarm but also the last British regiment engaged in the battle.

Yep, you guessed it, Gr Grandpa Dusenberry was among Coffin’s Dragoons from the time they were organized. I try to never let opportunity go by without mentioning him. 🙂

I first became interested in the American Revolution after watching Disney’s “Swamp Fox” when I was a kid. I have to admit I tended toward the romantic when younger, but reading over the years has tempered that tendency with reality. This paper gave me some insight into General Marion’s combat leadership skills, supported by the letters of some of his soldiers, which is a perspective that sometimes carries more weight than those of his superiors. Spending part of my formative years in Rhode Island, I became aware of the contributions of General Greene, which connected to the “Swamp Fox”. Over the years, I have expanded my interest and knowledge about the Revolution. But it all started with the “Swamp Fox.” Oh…and my interest in the Civil War started with the “Gray Ghost”, Mosby’s Raiders. 🙂

Thanks so much for this article. I am kin to Jehu Kolb, mentioned here. The article is very well written and informative.

Hi Jim, Enjoyed your article. My wife’s great(5) grandfather fought in this battle. Thomas Ray served in the North Carolina Militia, He was wounded and his brother Hudson was killed and another brother, Charles, was captured by the British. Are there any records of this battlefield where I might confirm this and perhaps find additional info on my wife’s ancestors? Thanks for any help in researching her wife’s family history.