In 1765 Parliament instituted a Stamp Act for the North American colonies, which proved wildly unpopular from Savannah to Halifax, and ultimately unworkable. The following year, there was a change of government in London. The new ministers repealed the Stamp Act, and across the ocean there was great rejoicing. However, those ministers also proposed a Declaratory Act establishing that, contrary to the arguments of Otis and others, under the British constitution Parliament did have the power to tax the colonies.

One of the few Members of Parliament to speak against the Declaratory Act was Charles Pratt, first Baron Camden (1713-1794), soon to be Lord Chancellor of England. He argued, as he had when the Stamp Act had been proposed, that since the colonists had no representatives in Parliament, by British tradition Parliament should not have the power to tax them. Very few M.P.’s agreed. Camden’s usual political ally William Pitt actually wrote the Declaratory Act. Lord Mansfield, the Chief Justice, announced that Camden was mistaken. Only four other Lords joined him in voting against the bill.

The debate over the Declaratory Act occurred shortly before London printers routinely reported Parliament’s proceedings in detail. But a few months later someone sent the text of Camden’s speech to printer John Almon (1737-1805), who included it in his Political Register magazine for September 1767. The printing staff set the text of that speech gingerly, perhaps as a thin guard against charges of sedition: they hid all the proper names, so the book reported “L— C——” speaking to the “B—— p———” on the issue of taxing the “A——— c——.”

But Camden’s philosophical position came through clearly:

My position is this—I repeat it—I will maintain it to my last hour,—taxation and representation are inseparable;—this position is founded on the laws of nature; it is more, it is itself an eternal law of nature; for whatever is a man’s own, is absolutely his own; no man hath a right to take it from him without his consent, either expressed by himself or representative; whoever attempts to do it, attempts an injury; whoever does it, commits a robbery; he throws down and destroys the distinction between liberty and slavery. Taxation and representation are coeval with and essential to this constitution. . . .

In short, my lords, from the whole of our history, from the earliest period, you will find that taxation and representation were always united; so true are the words of that consummate reasoner and politician Mr. [John] Locke.

As you can see, Camden’s argument was based on the linkage of taxation and representation. But nowhere in the speech did the baron use the famous phrase.

The Scots Magazine reprinted Camden’s speech later in 1767. The London Magazine, or Gentlemen’s Monthly Intelligencer ran the same text on two pages the following February. That magazine’s running head for the first page (i.e., the words in the top margin to guide readers to the contents of that page) was “L— C——’s Speech.” The second page was summed up this way:

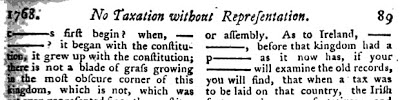

“No Taxation without Representation”

That page, published in February 1768 London Magazine, appears to be the launch of America’s great Revolutionary slogan. It debuted in big letters in a widely circulated, highly respected magazine. That short, rhyming summary of the argument below probably stuck in readers’ minds.

In 1769 the Rev. John Joachim Zubly (1724-1781) of Georgia authored a pamphlet titled An Humble Enquiry into the Nature of the Dependency of the American Colonies upon the Parliament of Great-Britain, and the Right of Parliament to Lay Taxes on the Said Colonies. He wrote:

In England there can be no taxation without representation, and no representation without election; but it is undeniable that the representatives of Great-Britain are not elected by nor for the Americans, and therefore cannot represent them…

Zubly went on to represent Georgia in the Second Continental Congress, but he eventually advocated reconciling with Great Britain. He died in Savannah after the British army had reconquered it, still a subject of the king.

By 1774, the words “taxation without representation” had become identified with the American conflict. Town meetings in Dover, New Hampshire, and York, Massachusetts (Maine), both issued statements using the phrase in January 1774. The sympathetic London clergyman James Burgh (1714-1775) included a chapter titled “Of Taxation without Representation” in his long book Political Disquisitions; or, An Enquiry into Public Errors, Defects, and Abuses. In July 1775, a suspected Loyalist locked up in a Connecticut prison even parroted the words back at his American captors. Early histories of the American conflict quoted the phrase, and Irish political activists also adopted it in the 1790s.

But whatever anonymous London Magazine printer came up with the headline “No Taxation without Representation” probably didn’t intend to coin a deathless slogan. He probably just wanted to summarize that page of the magazine in one line so he could move on to the next article.

One thought on ““No Taxation without Representation” (Part 2)”