Myth:

Myth:

“While Captain Molly was serving some water for the refreshment of the men, her husband received a shot in the head, and fell lifeless under the wheels of the piece. The heroine threw down the pail of water, and crying to her dead consort, ‘lie there my darling while I avenge ye,’ grasped the ramrod, … sent home the charge, and called to the matrosses to prime and fire. It was done… The next morning…Washington received her graciously, gave her a piece of gold and assured her that her services should not be forgotten. This remarkable and intrepid woman survived the Revolution, never for an instant laying aside the appellation she has so nobly won… the famed Captain Molly at the Battle of Monmouth.” – George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington (1860), first published in National Intelligencer, February 22, 1840

[Alternate ending]: “The activity and courage with which she performed the offices of cannonier during the action, attracted the attention of all who witnessed it, finally of Gen. Washington himself, who afterwards gave her the rank of Lieutenant, and granted her half pay during life. She wore an epaulette, and every body called her Captain Molly.” — Freeman Hunt, American Anecdotes: Original and Select (1830)

Busted:

Really? A lady lieutenant in the Continental Army – and receiving a commissioned officer’s half-pay for life? It’s a fantastical tale, and how we came to believe it is even more fantastical.

***

Just for a moment, let us imagine the story is true. Such remarkable effort, having attracted the notice of Washington and other officers, must surely have been celebrated by soldiers who witnessed it. Word would spread, and what a great story for the press! One newspaper would report it and others would certainly reprint that piece, as was the custom of the times. Such a sensation it must have caused. No wonder this heroine of the Battle of Monmouth was the “best-known” woman of the American Revolution, as current textbooks now declare.

But our heroine’s story was not repeated in all the papers, nor even in just one. Not until 1830, half a century later, did it begin to appear in print. Imagine, today, reading a tale of some heroic deed from the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba that had never before appeared in print and cannot be verified by any testimony dating from that time. Would you accept it at face value, no questions asked?[i]

When the story did first emerge, as we see in the quotations above, the heroine was called Captain Molly and she carried a pail of water, not a pitcher. This provides a clue to the genesis of the tale, for there was in fact a person called Captain Molly, a flesh-and-blood woman who resided in the Hudson Highlands after the war and according to official records received such things as a “bed-sack” and an “old common tent” from the government.[ii] Very likely, Captain Molly was Margaret Corbin, who fired her husband’s cannon when he was killed – not at Monmouth in 1778 but at Fort Washington in 1776. Wounded, Corbin became part of the “Invalid Regiment” at West Point and in 1779 was awarded a lifetime pension of a private soldier’s half-pay

Firing her husband’s cannon is a start, but what did Captain Molly have to do with a water pitcher? Pitchers are small, open containers, generally dinnerware, and it’s difficult to imagine people using them to cart water from place to place on a battlefield. Large quantities of water were carried in pales or buckets, small quantities in canteens. Why, then, did our heroine’s vessel change over time from a pail to a pitcher, and why did Molly herself become a Pitcher?

Don’t look for logic here, but there is a plausible folkloric explanation. One of the best-known women during the late eighteenth century was Moll Dimond Pitcher, a fortune-teller in Lynn, Massachusetts, who would counsel sailors and ship owners before they cast off to sea. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Moll Pitcher was a cultural icon – the butt of jokes, the subject of poems (John Greenleaf Whittier’s “Moll Pitcher and the Minstrel Girl”), and the protagonist of a popular melodrama entitled Moll Pitcher, or the Fortune Teller of Lynn that played on stages in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia from 1839 until after the Civil War.[iii] Moll Pitcher was a household name precisely at the time “Captain Molly” morphed into “Molly Pitcher,” and quite fortuitously, the word “pitcher” connoted the carrying of water to thirsty soldiers – a perfect match for Monmouth, where men literally perished from the heat.

In print, Monmouth’s heroine was first called Molly Pitcher in the late 1830s, and by the 1840s Moll Pitcher (the fortune teller) and Molly Pitcher (aka Captain Molly), as disparate as they were, had partially merged. When the fortune teller’s daughter died in 1841, an obituary noted that she was “the daughter of the celebrated Moll Pitcher.” A reader understandably asked which Moll Pitcher that might be, and the editor replied the heroine of Monmouth, then proceeded to tell the story of that battle.[iv] This mistaken explanation was picked up in several other papers. Much as the story of a woman firing the cannon of her fallen husband migrated from Fort Washington to Monmouth, so did the name “Moll Pitcher” transfer from one female protagonist to another. Over the next few generations, Moll Pitcher and Molly Pitcher, applied to a cannon-firing woman in the Revolutionary War, were used interchangeably.[v]

At first, the name “Molly Pitcher” was merely appended to the traditional “Captain Molly” story, but in time the dainty dinnerware, with its feminine connotation, proved irresistible. Having traded in her heavy pail for a pitcher, Molly was no longer a poor, vulgar camp follower, as contemporaries described the real-life Captain Molly of the Hudson Highlands, but a respectable woman in service of men. Defined by both a cannon and a pitcher of water, she now embraced a perfect blend of masculine and feminine attributes. That such a creature could be found in the middle of a Revolutionary battlefield was cause for wonder and celebration.

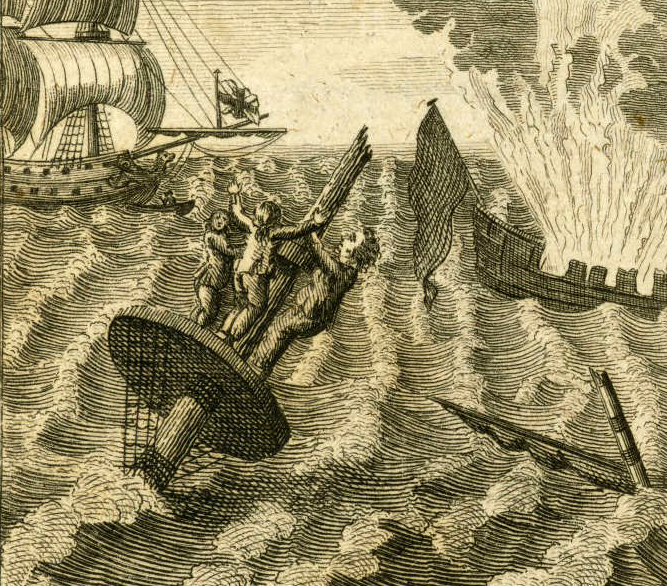

The combination of masculine and feminine imagery excited visual artists. In 1848 Nathaniel Currier, seventy years after the battle, painted a canvas titled “Molly Pitcher, the Heroine of Monmouth.” In the 1850s Dennis Malone Carter followed suit with two paintings, one of Molly by a cannon, the other of Molly being presented to Washington. By 1860 reproductions of engravings routinely bore the caption “Molly Pitcher” instead of “Captain Molly.” With visual images now leading the way, Molly Pitcher finally prevailed over the real-life Captain Molly.[vi]

Molly Pitcher remains with us today, her picture adorning our textbooks and her story placed front and center to show that women, too, were part of the Revolutionary War. Indeed they were. Thousands of camp followers cooked, washed, nursed, carried supplies, and no doubt made water available to sweltering soldiers. Very likely, some of these women helped fire cannons at Monmouth and elsewhere as well as at Fort Washington; artillery required a team effort, yet artillery teams were stationed in the rear, removed from close contact with enemy soldiers. I don’t mind if we call all these women Captain Molly, but please, not Molly Pitcher, that fair lass who carries water midst battlefield chaos in dinnerware and is rewarded handsomely by George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. Not in the Revolutionary War. It just wasn’t that way.

UP NEXT: The strange tale of a poor scrubbing woman from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, who died with no fanfare 54 years after the Battle of Monmouth, absolutely clueless that her name was Molly Pitcher (as the current American National Biography states), that she was the “best-known” woman of the Revolutionary War (as textbooks now describe her), or that General Washington had made her an officer in his army (as Wikipedia reports).

[i] Two sources are often cited, but neither counts as verification from that time. In 1830, fifty-two years after the Battle of Monmouth, Joseph Plumb Martin recalled seeing a woman and her husband working the artillery together, and a cannon ball passing between the woman’s legs. But Martin’s protagonist does not match our heroine: she carried no water to thirsty soldiers, she received neither recognition nor reward, and she did not spring to action because her husband was killed, for she had been helping all along. William Stryker, in the book The Battle of Monmouth (1927), quoted the diary of Dr. Albigence Waldo, which gave a second hand account of a woman who allegedly “took up” the “gun” (was it a musket or a cannon?) of her fallen “gallant.” The source is not direct, and the original diary is missing. This is worrisome. The revised 1862 edition of Dr. James Thacher’s Military Journal of the American Revolution, originally published decades earlier, contained some brand new material—an account of Molly Pitcher—even though Thacher himself had died in 1844 and never mentioned her in earlier editions. Without further evidence, we cannot say whether Waldo’s statement was contemporary to the time or whether it had been doctored to conform to a legend that had by then emerged, as Thacher’s was.

[ii] The “Waste Book for the Quartermaster Stores” and the “Letter Books of Captain William Price, Commissary of Ordinance and Military Stores,” in the West Point library. The numerous tents she received were possibly turned into clothing. Captain Molly was unable to care for herself, and money for her support was paid directly to her caregiver. (Edward Hall, Margaret Corbin: Heroine of the Battle of Fort Washington, 16 November 1776 [1932], 24–30.)

[iii] D. W. Thompson and Merri Lou Schaumann, “Goodbye, Molly Pitcher,” Cumberland County History 6 (1989), 15–16.

[iv] Emily Lewis Butterfield, “Lie There My Darling, While I Avenge Ye,” in Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History and Nation Making from Independence to the Civil War, Michael McDonnell, Clare Corbould, Frances M. Clarke, and W. Fitzhugh Brundage, eds., forthcoming in September 2013.

[v] In his editorial notes to Custis’s Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington (1861), Benson Lossing, who had interviewed elderly informants about the Captain Molly of the Hudson Highlands, refused to call Captain Molly by the name that was assuming greater popularity by that time, Molly Pitcher. “Art and Romance have confounded her with another character, Moll Pitcher,” he stated (225-26).

7 Comments

Can we even go as far as to say women likely fired cannon throughout the war (is there primary contemporary evidence for this being a common occurrence, except for M.Corbin)?

Good question. “Likely” might be too strong — perhaps go with “plausible.” Women were in the rear, as were artillery teams, so they likely helped with logistical support. Then why not pitch in with the firing teams if needed? Although Joseph Plumb Martin’s piece does not fit Molly PItcher, and although it was set to print in 1830, Martin’s narrative rings true and conforms to existing evidence in so many other ways. (See Phil Mead’s essay in Revolutionary Founders; Mead’s PhD thesis compares Martin’s narrative with the historical record, and Martin comes out smelling like a rose.) Martin made no special deal about the woman he saw firing a cannon; for him, at least — at least in his narrative — this was not a surprising occurrence. His story was about the trajectory of the cannon ball.

Again, this is not hard evidence, but it does help the case. So I’ll say plausible at the least, bordering on likely — admitting, of course, that we are still in the land of conjecture here.

Betsy Doyle was a similar heroine during the War of 1812 in New York. During an artillery duel between Fort Niagara and Fort George, whilst part of the American garrison at the former, she carried hot shot from the furnace to the battery on top of the “French Castle” or house, a considerable distance. A distinction should be made here between foot artillery and garrison artillery: foot artillerists were frequently in the line of fire at close range, while garrison guns were larger and often needed crews of 15 or 20 men to reload them. So its natural that working-class women were often volunteered to help man garrison guns. It’s interesting that the two most strenuous positions on a gun crew, ramming and carrying shot, were in these cases taken by women volunteers.

Fascinating! Do you have any sense of why this story would be popularized in the 1830s? What was going on in the country that there would be an interest in women as war heroes?

Thanks for the article — really enjoyed it.

Alex