Over the course of time, many fashions change. The hem lines on women’s skirts rise and fall, folks give up hula-hooping for jogging, and emus replace llamas as the trendy exotic livestock to raise.

So it is with food fashions, as well. Reading “receipt books” – cookbooks – of the Revolutionary era, one is struck by the many changing trends in cooking. Puddings are often savory main-course dishes, and are frequently tied up in a cloth and steamed. In meats, much of what we today grind up and use in dog food or bologna was routinely used in the kitchen. The spices called for in these recipes are, for the most part, familiar, although they’re used in unfamiliar ways and sometimes called by unfamiliar names.

For example, “Jamaica pepper” (allspice) does, indeed, look like peppercorns (“Siam pepper”), although, of course, allspice has a completely different flavor from black pepper – and you wouldn’t want to confuse the two in a recipe! More importantly, the ways in which these spices are used has seen some change over the past couple of hundred years, and today’s menu reflects some of those changes.

We’re going to explore how sweet and savory have shifted from being part of a continuum of flavors as used on the Revolutionary table, to having pretty strictly-defined roles today. Where sweet spices and sweetened dishes are largely confined to the dessert menu today, they were used throughout the meal then.

Furthermore, sugar was quite dear, and much more difficult to use, as it was generally supplied in hard loaves of white sugar or very large cones of brown sugar, from which the cook had to carve the appropriately-sized chunk, hand-grinding it to powder in order to make it usable in a recipe. Molasses and maple syrup were widely used, but these have distinctive flavors of their own, and so are not simply substitutes for the cheap, easily-used granulated white sugar in your countertop canister.

So our main course will use somewhat more sweet spicing than a modern palate expects, and the dessert course will be somewhat less sugared. The side dish gets a sweetness boost from being made from sweet potatoes, and dessert uses barley in a dish where we would not today expect to see it.

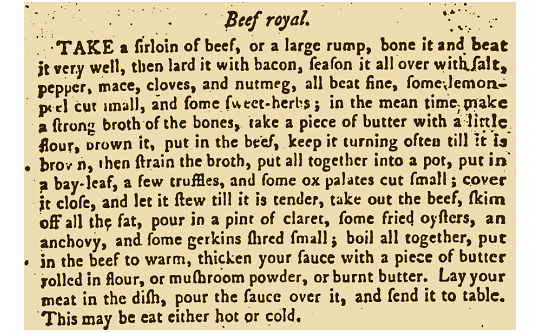

Sweet Potato Pudding[i]

We’ll start with a dish that’s called a pudding, keeping in mind that many “puddings” were made with various meat, suet and so on. This one is closer to our modern conception of a pudding than some, and while it’s relatively sweet, it complements the main course nicely.

Preheat the oven to 350° F (175° C) and grease a 2-quart casserole. Peel and cube:

2 cups (450ml) sweet potatoes

Boil until they’re softened, and then remove them from the water and mash them. Separate:

3 eggs

Beat the egg yolks lightly and stir in the mashed sweet potatoes until smooth. Stir in:

1/4 tsp (2ml) ground nutmeg

1/4 tsp (2ml) ground cloves

1/2 tsp (3ml) ground cinnamon

1/2 cup (115 ml) sugar

1/2 c (115 ml) butter, melted

2 tbsp (30 ml) red wine

2 tbsp (30 ml) brandy

1/2 cup (115 ml) milk

Blend thoroughly. Beat the egg whites to stiff peaks, but not dry, and then gently fold them into the sweet potato mixture. Heap the mixture into the greased casserole and bake for one hour, until lightly browned on top.

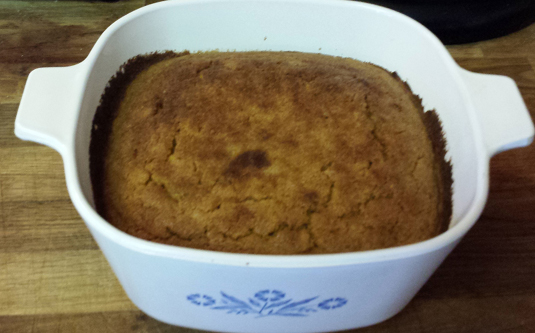

Beef Royal[ii]

For the main dish, we’re turning to one of the most popular cookbooks of the day, Hannah Glasse’s venerable The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy: Which Far Exceeds Any Thing of the Kind Yet Published. (And I thought that my book titles were unwieldy!) We’ll follow the original recipe for the seasoning of the meat, but we’ll depart from it somewhat for the gravy, as truffles are prohibitively expensive and ox palates fall into the category of bologna ingredients today.

To break up the proteins in the meat and tenderize it, start by beating with a mallet:

2-3 lb (1-1 1/2 kg) beef sirloin or rump roast, boneless

If it is a lean cut of meat, you may choose to lard it, which means simply poking holes into the roast and threading bacon or other fatty lardoons through the meat, so that it doesn’t cook up too dry. What I had available was actually a chuck (shoulder) roast, which was quite well-marbled, and so it did not require this treatment.

Blend together:

2 tsp (10 ml) salt

1 tsp (5ml) pepper

1/2 tsp (3 ml) ground mace

1/2 tsp (3 ml) ground cloves

1 tsp (5 ml) nutmeg

1 tsp (5 ml) grated lemon peel

1 tsp (5 ml) thyme flakes

1 tsp (5 ml) sweet basil flakes

1/2 tsp (3 ml) rubbed sage

1/2 tsp (3 ml) tarragon

Pat onto all sides of the meat and set it aside for a moment. In a large pot, melt:

3 tbsp (45 ml) butter

Whisk in until smooth:

3 tbsp (45 ml) flour

Put the meat into the pot and brown it on all sides. Add to the pot:

4 cups (900 ml) beef broth

1 bay leaf

1 cup (225 ml) diced mushrooms

Cover tightly and stew until tender (approximately 2 hours). Remove the meat from the broth and add:

2 cups (450 ml) red wine

2 tbsp (15 ml) Worcestershire sauce

1/4 cup (60 ml) sweet relish

In another small saucepan, melt:

4 tbsp (60 ml) butter

Whisk in until smooth:

4 tbsp (60 ml) flour

Whisk the butter mixture into the broth and continue stirring until it has thickened into a gravy. Return the meat to the pot to warm it through, and serve with the gravy poured over the meat.

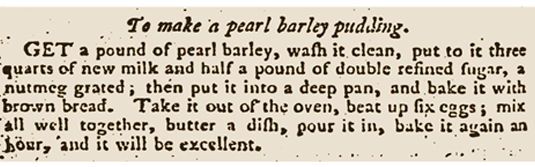

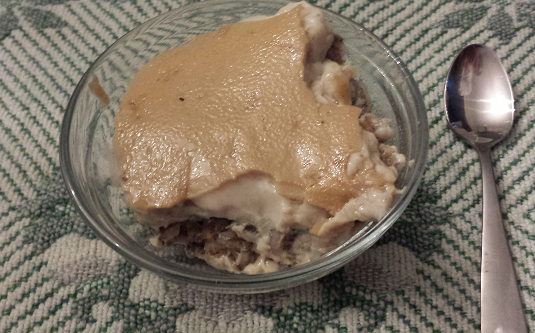

Pearl Barley Pudding[iii]

We’ll scale this recipe down a bit, to make an amount appropriate to our table. Preheat the oven to 350° F (175° C). In a large Dutch oven, mix together:

1 1/8 cups(250 ml) pearl barley

6 cups (900 ml) whole milk

1/2 cup (115 ml) granulated sugar

3 tsp (15 ml) grated nutmeg

Cover and bake for approximately an hour, until the barley is tender. Beat until foamy:

3 eggs

Temper the eggs by slowly whisking some of the hot milk from the barley mixture into them, and then mix the tempered eggs into the barley and milk. Return the pudding to the oven for another hour to hour and a half, until the top is browned and set. Serve warm.

Conclusions

All of the dishes in this meal served a table of eight quite adequately, and we enjoyed it with a loaf of homemade pumpernickel bread and some steamed peas – if we were being completely faithful to the period, we’d’ve had pease porridge instead – and a nice cabernet sauvignon. The sweet potato pudding and beef were very popular, and, not surprisingly, the barley pudding underwhelmed our palates’ desire for sweet when presented as a dessert.

[i] O’Connor, Hyla. The Early American Cookbook. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1974. 114. Print.

[ii] Glasse, Hannah. The art of cookery, made plain and easy. London: W. Strahan, J. and F. Rivington, J. Hinton, 1774. 42. Web. http://books.google.com/books?id=xJdAAAAAIAAJ.

[iii] Glasse, Hannah. The art of cookery, made plain and easy. London: W. Strahan, J. and F. Rivington, J. Hinton, 1774. 210. Web. http://books.google.com/books?id=xJdAAAAAIAAJ.

4 Comments

Are we sure that “gherkins shred small” translates to “sweet relish”? I was with you right up to that point – red wine and sweet relish…(shudders).

And thanks for doing this – I don’t recall if we ever got onto this subject when you were in Columbus – but I have a modest collection of antique cookbooks myself (including slobovian ones). Fascinating.

Faye, you may be right, as “gerkin” is a generic term for a small cucumber. However, Glasse elsewhere explicitly refers to “pickled gerkins, sliced” as an addition to another gravy (Portugal beef, page 41). Her pickled gherkin recipe does not have sugar in it, though it does feature cloves, mace and ginger, so it would be in line with the flavors already present in this dish.

I could see an argument for making this dish with either her pickled gherkins or fresh cucumbers, but given the overall sweetness of the gravy, I opted for the pickled relish, and it was delicious – we saved the leftover gravy for use in a future soup. If you make it the other way, let me know how it turns out.

Really nice topic Lars. I am really enjoying the recipe section. Thanks.