Myth:

Myth:

During the ratification debates The Federalist Papers, with their reasoned arguments, convinced people to vote in favor of the Constitution.

Busted:

Numbers suggest a different story. The newspaper essays we now celebrate were less widely circulated than many other Federalist and Anti-Federalist tracts, book sales were miniscule, and references to them during the extensive public debates were few. We have no indication they affected the election of delegates to the state ratifying conventions, and even at those conventions they played no large role. The way we treat The Federalist Papers now, compared with how they were treated then, is a classic example of reading history backwards.

***

An opening caveat: Nothing I say below in any way denigrates the 85 essays written under the pen name of Publius in 1787-88. I talk only about the historical impact of those writings at the time, as distinguished from how we treat them today.

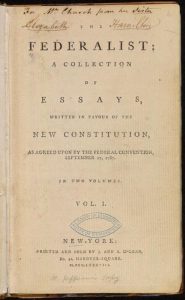

For starters, the name. Founding Era Americans knew nothing of “The Federalist Papers.” In 1788, as the Constitution was being debated, citizens in New York City, and a few elsewhere, might have read newspaper articles called The Federalist, and a select group had access to the two bound volumes bearing the same title. The Federalist did not become The Federalist Papers until the mid-twentieth century. In the 1940s some authors and publishers added “papers” to “Federalist” to signify particular essays they discussed or published, and then in 1961 the New American Library, under its Mentor imprint, boldly place “The Federalist Papers” on its cover and title page. “Good reading for the millions” was Mentor’s slogan, but the editors likely felt that “the millions” might have some trouble with eighty-five ponderous essays written for a very different audience. The original, obscure title only compounded that problem. Was “The Federalist” a person? a political party? a document? a philosophy? The reifying, self-reflexive new title, Federalist Papers, provided clarity and gave the work a physical stamp. The Mentor edition of “The Federalist Papers” circulated widely, and the name took hold. To this day, Publius’s essays bear the label bequeathed to them by twentieth century commercial publishers.

Now the numbers. The eighty-five Federalist essays were part of a grand debate over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but they were scarcely the whole of it, as it would seem today from the amount of attention they receive. In addition to Publius, several writers published serial essays in the newspapers under pseudonyms also drawn from Roman history: Caesar, Brutus, Cato, Fabius, Cincinnatus. The Wisconsin Historical Society has collected and reproduced these arguments in twenty-two hefty volumes and multiple microform supplements entitled The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (DHRC), and the project is not yet finished. Since five of the original thirteen states are not yet covered, editors project six more volumes on ratification and still more on the Bill of Rights. The Federalist essays fill less than one of these volumes.

During the ratification debates, essays for or against the Constitution would appear first in one paper and then get reprinted in others, often in distant cities. By looking at how many times each essay was reprinted, we can get an idea of the interest that piece of writing induced, and that can give us some sense of its impact on the reading public. DHRC editors have tabulated the known reprints of these essays and articles, Publius’s included. The first five “Federalist” entries were reprinted in an average of eight papers outside of New York state, a respectable circulation, but then out-of-state publication fell off dramatically. After The Federalist No. 16, no essays were printed in more that one paper out of state, and following The Federalist No. 23, the remaining 62 essays never made it across New York’s borders at all, except for an excerpt from The Federalist No. 38 in the Freeman’s Oracle, published in Exeter, New Hampshire.[1]

By contrast, James Wilson’s speech in support of the Constitution, delivered at the State House Yard in Philadelphia, was reprinted in its entirety in twelve of the thirteen states, appearing in 34 newspapers and in several pamphlets as well, in 27 different cities or towns from Portsmouth to Augusta. Altogether, some 250 essays and articles appeared in newspapers in six states or more, a broader circulation than for any of the “Federalist” pieces except the first. Publius’s last seventy essays stand as anomalies, the least likely pieces to have appeared in more than one state.[2]

In the battle for public opinion, Publius’s newspaper publications enjoyed no special standing. But what about the bound volumes?

The Federalist, in its book form, did not have the impact on ratification that Thomas Paine’s Common Sense did on declaring independence. Compare the print runs: at least twenty-five print runs of Common Sense, totaling tens of thousands (although not Paine’s own inflated estimates of 100,000 or 120,000 or 150,000) versus 500 copies of The Federalist, with many of these left unsold at the close of the ratification debates.

A timeline is instructive. Six states had already voted for ratification before the first volume of collected essays appeared on March 22, 1788. The nation was only three states shy of the number required to place the Constitution in effect. By May 28, when the second volume appeared, Maryland and South Carolina had already ratified, and only one more state was needed. In the remaining states – New Hampshire, Virginia, New York, and North Carolina (Rhode Island did not hold a convention) – delegates had already been selected. Madison’s essays on federalism and the relationships between the three branches or Hamilton’s extensive treatment of the presidency, so widely noted today, had not yet appeared in pamphlet form, nor had they circulated in newspapers out of New York, when citizens cast ballots for delegates supporting, opposing, or questioning the proposed Constitution.[3]

One other question remains: Might the combined volumes, although appearing too late in the game to affect delegate selection, still change minds at the conventions? Hamilton and his allies certainly hoped so, and they worked hard to put copies in the hands of delegates to the four remaining conventions – but theirs were not the only essays to circulate. As Federalist delegates sharpened their arguments with whatever writings might help, so did their opponents, and there is no indication that arguments unique to Publius changed any minds. In the final stage of the propaganda war, Publius was but one player among many.

Even in New York (Publius opened each essay with the salutation, “To the People of the State of New York”) we have no evidence that The Federalist was a game changer at the state’s ratification convention. Initially, the convention had a strong Anti-Federalist bent. Of the 65 delegates, 46 were “decidedly opposed to the constitution,” according to the election returns reported in the New York Journal. While we might like to imagine that last minute input from The Federalist converted Anti-Federalists, it was the arrival of late-breaking news that turned things around. On June 24, delegates learned that New Hampshire had voted for ratification, so the Constitution would take effect no matter what New York did. A week later they discovered that Virginia, the largest state in the union, had also signed on, so if New York failed to ratify it would be on its own. After that, the critical issue was no longer outright acceptance or rejection but whether to call for a second constitutional convention to consider amendments that would make the Constitution more palatable to the convention’s Anti-Federalist majority.[4]

While Publius’s first eighty-four essays did not address that matter, an unrelated, widely circulated nineteen-page pamphlet from the pen of Federalist contributor John Jay did. Writing under the pseudonym “A Citizen of New-York,” Jay argued persuasively that a second convention, colored by the contentious debates over ratification, would be so highly politicized that it could destroy the nation. Noah Webster, a Federalist editor, wrote that Jay’s argument was “altogether unanswerable.” Another writer stated that Jay’s pamphlet “has had a most astonishing influence in converting Antifeoderalists, to a knowledge and belief that the New Constitution was their only political salvation.” Alexander Hamilton was also impressed with Jay’s pamphlet. In fact, when he finally argued against a second convention in the concluding Federalist essay, he simply directed readers toward Jay:

“The reasons assigned in an excellent little pamphlet lately published in this city,are unanswerable to show the utter improbability of assembling a new convention, under circumstances in any degree so favorable to a happy issue, as those in which the late convention met, deliberated, and concluded. I will not repeat the arguments there used, as I presume the production itself has had an extensive circulation. It is certainly well worthy the perusal of every friend to his country.”[5]

By any measure, Jay’s Address had a greater impact on the New York Convention than did Federalist No. 85, which appeared in the second volume after the elections for delegates and only days before the convention, and which did not appear in any newspapers until mid-August, well after New York had ratified the Constitution. In the final analysis, though, the outcome was more the result of outside events and the subsequent maneuverings of the delegates, Hamilton included. To win Anti-Federalist votes, Federalists agreed to issue a call for a second convention – but only after ratification. It was a strictly political solution and Publius’s essays had no hand in it.[6]

This suggests a larger issue to ponder. When we look at political debates of the distant past, we can read and get the gist of the rational arguments presented by both sides – but we can’t understand the context for those arguments without immersing ourselves deeply in those times. In the end, the political considerations of the moment, not abstract reasoning, were more likely to have carried the day.

[1] DHRC 13:490 for Madison’s and Washington’s attempt to circulate The Federalist in Virginia. DHRC 19:540-49 for newspaper publication of Publius’s essays.

[2] DHRC 13:337-38 and 344 for newspaper publication of Wilson’s speech. For reprinting of more than 800 essays and articles from the ratification debates, see the appendices in DHRC, volumes 13-18. For a visual representation of how Publius compares to the others, note in particular 15:575-79, 16:597-600, and 18:407; there, if a piece appears in only one state, the odds are strong that it’s one of Publius’s. It can be argued that newspapers didn’t reprint Publius once bound volumes were promised, but since the second volume, which included the majority of the essays, did not appear until very late in the game (see below), this excuse cannot be used to promote their impact.

[4] New York Journal, June 12, 1788, in DHRC 21:1582. The Anti-Federalist landslide might have been slightly exaggerated by the sympathetic New York Journal, but the Albany Gazette, June 5, 1788, gives a preliminary report of a 2-to-1 Anti-Federalist majority. (DHRC 21:1581.) Publius’s newspaper articles had not effectively quelled the Anti-Federalist landslide. Following Federalist No. 21, only one of the remaining 64 essays appeared in any of the state’s papers north of the city. (DHRC 19:540-49.)

[5] Jay’s Address to the People of New-York, on the Subject of the Constitution was published two weeks before New York’s elections for delegates, and numerous contemporary reports suggest that it had it not been published, the Anti-Federalist majority at the convention would have been greater yet. For its influence, see Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 336-38 and DHRC 20:922-42. Webster quote: DHRC 20:924. The conversion quotation, one of several testifying to Jay’s influence, is from Samuel Blachley Webb to to Joseph Barrell, April 27, 1788, ibid., 924. Jay’s Address was reprinted in its entirety in serial form in seven out-of-state newspapers, a mark no group of Publius’s essays ever achieved. Federalists focused specifically on circulating it in New Hampshire, which soon became the ninth and deciding state to ratify the Constitution. See also above, Chapter 4, note XX.

[6] Reprints of Federalist No. 85: DHRC 18:137. To win enough Anti-Federalist votes for ratification in New York, Federalist delegates did allow the New York Convention to call for a second constitutional convention, but this would be only to consider proposed amendments. Jay’s concern was that to call a second convention without first approving the results of the first would produce political bedlam, and in light of the political discord already displayed in the ratification debates, that argument, in the words of Federalist Noah Webster, was “altogether unanswerable.” (DHRC 20:924.)

6 Comments

Excellent topic Ray. Ever taken a look at the overwhelming belief that John Marshall was first to use Judicial Review?

The Constitution says nothing about who should interpret the Constitution. In the Early Republic, Congress thought it had that power, presidents thought they did, the Supreme Court thought it did – and the people, meanwhile, believed they did. The first time the High Court assumed for itself the power to determine the constitutionality of the law was not Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison (1803) but a unanimous decision in Hylton v. United States (1796). Here’s the backstory, which I include in Constitutional Myths. In 1794, to provide revenue for an array of defense measures (fortifying harbors, establishing armories, enlisting soldiers, and building or purchasing armed ships), Congress levied what we call today luxury and sin taxes on imported wines and spirits, refined sugar, and snuff. These excise taxes were clearly authorized by the Constitution, but when Congress also levied a tax of sixteen dollars for every carriage, some argued that this was a tax on ownership rather than on economic activity, making it a direct tax that needed to be apportioned among the states. Massachusetts Representative Theodore Sedgwick, a defender of the tax, countered: “It would astonish the people of America to learn that they had made a Constitution by which pleasure carriages and other objects of luxury were excepted from contributing to the public exigencies.” Apportionment would not work, he continued, because several states “had few or no carriages.” Daniel Hylton, a Virginian who owned 125 chariots for his personal use, refused to pay the tax. His case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled that the tax was an excise and did not have to be apportioned among the states, so it was indeed in accordance with the Constitution. Hylton had to pay the tax.

Thanks for the reply. That is indeed an interesting case. I did not previously know about it. However, I think there may be an earlier example of Judicial Review. Have you also looked at the Invalid Pension Act case decided while John Jay was the Chief Justice? In 1792 Congress passed the Invalid Pensions Act which required the justices to review pension files and make determinations of validity and of the amount. John Jay biographer, Walter Starr, had this to say:

“Jay and his colleagues considered the Pension Act unconstitutional, although they did not use that dramatic term. They noted that Congress could only assign to the federal courts duties which ‘are properly judicial,’ and opined that the duties assigned to the Circuit courts under the new Act ‘are not of that description,’ because their decsions were subject to review by both the executive and legislative branches. The judges would therefore construe the Act as appointing them as ‘commissioners’, and they agreed to serve as such ‘between the adjournments’ of the circuit courts. In other words, by a clever construction, Jay and his colleagues managed both to signal their concern about the constitutionality of the Act and their willingness to process the applications. This opinion may be the first instance of a federal court reviewing a federal statute to determine whether it was consistent with the Constitution. It was also the first instance of what is now accepted principle, that courts will if possible construe statutes to avoid finding them unconstitutional.”

Very interesting, Wayne. I was not familiar with this case. It was indeed a “clever construction,” as was Marshall’s strategy in Marbury v. Madison, and in both cases you can see justices using what we now call judicial review strategically. The Hylton case was more straightforward. Here’s what I wrote in Idiot’s Guide to the Founding Fathers about the historical context of judicial review in the founding era, before it was firmly established, and various responses to it:

Before 1776 Americans did not look fondly upon judges, who were appointed by the Crown and beholden to it. Administration of justice was not separated from the executive authority; it was just the reverse, with judges directly influenced by a king or his appointed colonial governors. Revolutionaries changed that when they wrote new state Constitutions and established separate judicial branches, making judges responsible to the people.

States were now free of Britain and on their own, and state legislatures busily attempted to pass laws that would cover any and every circumstance that might arise. In this new order, judges were to follow these precise new codes and not exercise individual discretion. A judge should be “a mere machine,” Thomas Jefferson pronounced in 1776.

But by the 1780s, some people began to worry that the legislatures were going too far in their law making. Upper class people in particular feared that legislatures, influenced by debtors and poor folks, would pass laws for debtor relief and the issuing of paper money. Who, then, would prevent “legislative tyranny”?

There were competing ideas on that score, but one possible solution was for judges to step in and impose certain limits on the legislatures, based on written state constitutions. “Here is the limit of your authority, and hither, shall you go, but no further,” Judge George Wythe instructed the Virginia legislature in 1782. The state’s Attorney General Edmund Randolph initially opposed Wythe’s view but then came to agree with him. “Every law against the constitution may be declared void,” he said. Still another judge, Edmund Pendleton, admitted he had no answer to this predicament but knew the question of whether a judge could invalidate a law presented “a deep, important, and I will add, a tremendous question.”

A “tremendous question” indeed, and definitely with huge “consequences.” Broadly speaking, there were three responses to the notion of judicial nullification, as it was called at the time, or judicial review, as we call it today.

Response Number One: Judicial review was absurd. How could judges, who were generally not elected but appointed, and who weren’t supposed to make laws, overrule legislatures, which had been elected and were told to make laws? Judicial review suggested that the people could not be trusted with their own government. For many, that was an insult to popular sovereignty. There was a much better way to check a tyrannical legislature: the people themselves could throw the bums out at the next election.

Response Number Two: Judicial review was both beneficial and necessary. This process, and this process alone, protected the constitution, the document that had been written by and for the people. If a law passed by a legislature contradicted a state’s constitution, and the matter came before a judge, how could he ignore the constitution? It was the “fundamental law” or the “superior law,” the very basis of the people’s government. Never should legislators overrule it. Judges were there to make sure they didn’t. They had taken a vow to uphold a constitution and thereby protect popular sovereignty.

This view was just beginning to take hold when the Federal Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787. North Carolina Supreme Court Justice James Iredell, one of the first and most eloquent proponents of judicial review, wrote to a delegate who was attending the Convention. A constitution, he said, is not “a mere imaginary thing, about which ten thousand different opinions may be formed, but a written document to which all may have recourse.”

Iredell argued that if all had “recourse” to one federal constitution, and if its stipulations and rules superseded any others, judges could cite that document in order to toss out unjust laws. They could use it as a reference point when some wanted a law that others resisted. Without the clarity such a constitution provided, civil unrest would ensue, Iredell cautioned—and that was a dangerous prospect. He valued constitutional guarantees that protected minorities and minority opinions, too. Without those, people would join the majority just to be safe. They would be forced to “sacrifice reason, conscience, and duty, to the preservation of temporary popular favor.”

Response Number Three: Madison and Jefferson, among others, thought that judges should treat the Constitution as the prevailing standard. But so should other arms of government, which had “a concurrent right to expound the Constitution,” Madison said. No arm, in this view, had the final word when deciding what was constitutional and what was not, and no arm could intrude into the sphere of the other. If branches disagreed, then “an appeal to the people themselves can alone declare its true meaning, and enforce its observance,” Madison wrote.

Madison’s argument, though attractive, was of little help to judges. If they were charged with upholding a law that appeared to contradict the Constitution, which rule should they uphold? They needed to rule on the case before them, not wait around for “the people themselves” to settle the matter. This hands-off approach faced another problem as well. If neither the courts nor any other body had the final word on enforcing the Constitution, the separate branches of government, and the people themselves, were left to duke it out, without any guidelines to govern their fight. The consequences of that, like the consequences of judicial review, would be “tremendous.”