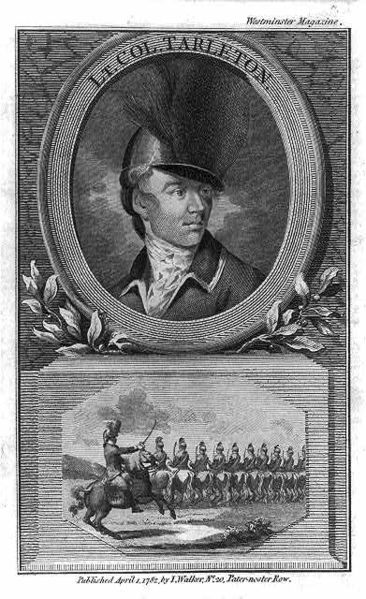

On the morning of January 17, 1781, Lt. Colonel Tarleton led a British army against Daniel Morgan at a place called the Cowpens. We all know that Morgan treated the rash young officer to ‘A Devil of a Whippin’. However, even with the setback, Lord Cornwallis remained determined to make his invasion of North Carolina. He had started the South Carolina campaign by turning Tarleton and the British Legion loose against Col. Buford at the Waxhaws. The result was a double-edged sword. The public was momentarily awed and pacified but, as word of the brutality circulated, many people in the back country returned to a state of armed rebellion that plagued Cornwallis continuously during the occupation of Georgia and South Carolina. Now turning his attention to North Carolina, Cornwallis made a similar mistake sending Tarleton and the Legion in pursuit of the militia retreating from Cowen’s Ford.

***

Banastre Tarleton spent the afternoon and night of January 17, 1781 riding to Hamilton’s Ford so he could regroup and gather up whatever portion of his recently defeated army evaded capture after the disaster at Cowpens. Soldiers trickled in throughout the evening and into the following day. Almost all of the Legion Dragoons showed up along with ‘several’ of the men from other regiments.[i] One company of Legion dragoons missed the camp at Hamilton’s instead riding directly to Cornwallis at Turkey Creek which was about 25 miles from the battlefield. They arrived ahead of Tarleton and had already provided General Cornwallis news of the events at Cowpens prior to his arrival on the morning of the 19th.[ii]

While Tarleton traveled on the 18th, General Leslie finally arrived at Cornwallis’s camp on Turkey Creek with his reinforcements for the British Army. His additions gave Cornwallis something like 1,950 British Regulars and 460 Provincials. Of all the Provincial regiments raised in New York and brought south, only the British Legion remained with Cornwallis for the invasion of North Carolina.[iii] The other Provincial regiments would remain in South Carolina as occupation forces under the command of Lord Rawdon.

Once he had the situation fully explained, Cornwallis quickly saw the need to catch Morgan and retake the prisoners taken at Cowpens. He dispatched Tarleton and the Legion back across the Broad River toward the battlefield in search of information on rebel movements. Even before getting to the battlefield, Tarleton received word Morgan had moved his army across the Broad at the upper fords and was moving back to North Carolina for a rendezvous with Greene. To succeed, Morgan would need to get his army across the Catawba over 50 miles away.[iv]

Moving as quickly as possible considering the large baggage train, Cornwallis started the main army toward Ramsour’s Mill hoping to get ahead of Morgan. They arrived on the 25th to find that Morgan was already across the Catawba a few miles away at Sherrald’s Ford. Recent rains upstream continued to swell the waterways making movement with the wagons all but impossible. The army had traveled only 30 miles in over 3 days of marching. At this point, Cornwallis made the decision to jettison all his excess baggage (including the rum stores) and convert his entire army into the equivalent of light troops. The army remained anxious to avenge the recent losses at Cowpens and met the decision with “the most general and chearfull acquiescence.”[v]

As it turned out, the big bonfire and dramatic decision to burn all the baggage may have been just a tad premature. Even without the train Cornwallis continued moving incredibly slowly. The Catawba River swelled and rebel forces infested all the known fords in the area. Morgan’s corps moved on toward Salisbury to join with Greene while rebel militia under General Davidson prepared to give the British a warm welcome to North Carolina.

While trying to give the impression he would attempt to cross at Beattie’s Ford about 35 miles above Charlotte, Cornwallis steered close to a private ford discovered a few miles below Beattie’s. In the early hours of February 1st, he led three infantry regiments and the British Legion in an amphibious assault across the Catawba at Cowan’s private crossing.[vi]

To call Cowan’s a ford is a bit generous. Particularly so in late January 1780. Reports from the event show the Catawba swollen with flood waters and ranging from 400 yards to half a mile in width. After the war, Joseph Graham described Cowan’s ford as being variable in depth with a rocky bottom. It was normally about 400 yards wide. The main track started from the western shore (the British side) and continued about 2/3 of the way across to an island in the river. At that point, the ‘wagon ford’ continued forward. It was deeper but provided an exit from the river with a limited amount of sharply rising slope. The ‘horse ford’ turned downstream from the mid-point and made for a longer crossing but was not so deep.[vii]

As the army arrived, rain started falling again making Cornwallis even more determined to make the crossing immediately. His intelligence showed Greene already in Morgan’s camp moving toward the Yadkin. Even as he approached Cowan’s Ford, General Cornwallis could see rebel fires on the far side of the river. He was disappointed to see his movements had not fooled General Davidson whose militia waited for the British attempt.[viii] In fact, Cornwallis could clearly see rebel riflemen poised in excellent positions on high hills directly above the river crossing.[ix]

Sgt. Lamb of the 23rd Fuzileers provided a detailed account of the actual crossing. “Lord Cornwallis, according to his usual manner, dashed first into the river, mounted on a very fine and spirited horse, the brigade of guards followed, two three pounders next, the Royal Welch Fuzileers after them.” As the first group approached the river’s midpoint, rebel riflemen started taking their toll on the column. Caught up in the fast moving current, Sgt. Lamb instructed his men to hold tightly to each other and ignore the bullets striking the water around them. In front of his group, in about four feet of water, one of the artillerymen lost his footing and started to thrash helplessly down the river. Recognizing the man as an irreplaceable part of the artillery unit, Lamb broke from his men and took off swimming downstream to rescue the gunner. All the firing stopped on both sides as men watched the pursuit. Lamb took about ten full strokes and grabbed the thrashing man. They struggled for a moment before the gunner found his footing and then pushed back against the current to regain their position with the column. Only at that point did the Americans return to their sniping.[x]

Sgt. Lamb continued, “After this affair the enemy began again a very heavy fire upon us, nevertheless our divisions waded on, in a cool intrepid manner, to return their fire, being impossible, as our cartouch boxes were all tied at the back of our necks. This urged us on with greater rapidity, till we gained the opposite shore, where we were obliged to scramble up a very high hill under, a heavy fire; several of our men were killed or wounded before we reached the summit. The American soldiers did all that brave men could do, to oppose our passage across the river, and I believe not one of them moved from his post till we mounted the hill, and used our bayonets; their general was the first man that received us sword in hand, and suffered himself to be cut to pieces sooner than retreat; after his death, his troops were soon defeated and dispersed.” He went on to point out each British soldier carried a full pack and load of ammunition along with their muskets and bayonets. The rushing river came up to their chests and “three hundred of their enemies (accounted the best marksmen in the world) placed on a hill as it were over their heads, keeping a continual and very heavy fire upon them.” [xi]

Cornwallis had sent Brigadier General O’Hara with the Brigade of Guards to lead the river assault. Even though O’Hara had a bad moment with his horse losing its feet and rolling over him about 40 yards down the current, the Guards moved steadily across without stopping to return fire. Cornwallis praised them, “Their behavior justified my high opinion of them, for a constant fire from the enemy in a ford upwards of 500 yards wide, in many places up to their middle with a rocky bottom and strong current, made no impression on their cool and determined valour nor checked their passage.” The light infantry landed first and formed with bayonets. General Davidson of the rebel militia opposed them with some 300 militia. The general was killed right away and the militia dispersed. Cornwallis listed his loss as one Lt. Colonel and 3 other men killed. He also listed 36 men wounded. All of the casualties came from the Brigade of Guards leading the assault.[xii]

With all due respect to Lord Cornwallis, there seems to be substantial evidence casting doubt on his estimate of the losses at Cowan’s Ford. The records of troops fit for duty in North Carolina show 690 men present and fit in the Brigade of Guards on Feb 1 but only 605 on March 1. A difference of 85 men. The other two infantry regiments crossing that night were the 23rd and the Bose regiment. They show a decline in manpower for the same period of 21 and 32 respectively.[xiii] The total losses over the one month period are 138 men for these three regiments yet there are no other major skirmishes in the month of February 1781 to account for losses greater than about a dozen soldiers from those regiments. There is also ample eyewitness testimony to substantiate greater British losses at Cowan’s Ford. A tory with Cornwallis named Nicholas Gosnell said, “I saw’em hollerin’, a’hollerin’ and a’downin’ – the river was full on’em a-snortin’, a’hollerin’ and a’drownin’ until his Lordship reached the off bank; then the Rebels made straight shirttails [ran], and all was silent. .”. From the Patriot side of the river, Robert Henry believed there should have been a great discrepancy between those British killed and those wounded. He explained that, “when a man was killed or badly wounded, the current immediately floated him away, so that none of them that were killed or badly wounded were ever brought to the shore; and none but those slightly when reached the bank; Col. Hall fell at the bank.” The next morning Henry and his friends crossed the river in a canoe. They went to James Cunningham’s fish-trap looking for some breakfast but instead found 14 dead men. Several of the men had no wounds, but had drowned in the strong currents. Robert Henry concluded his account by adding that ” a great number of British dead were found on Thompson’s fish-dam, and in his trap, and numbers lodged on brush, and drifted to the banks; that the river stock with dead carcasses; that the British could not have lost less than 100 men on that occasion.”[xiv]

According to Tarleton, once the Brigade of Guards cleared the way, “The Regiment of Bose, the 23rd, the three pounders, and the cavalry, followed in succession. When the passage was completed, Earl Cornwallis directed Lieut. Col. Tarleton to move forwards with his own corps and the 23rd Regiment, to attack rear of the camp at Betties.” As the Legion rode up the 4 mile track to Beattie’s Ford, it soon became clear the rebels had abandoned that position also. On receiving the news Cornwallis ordered Tarleton to take the cavalry on a patrol into the countryside looking for information on the enemy.[xv]

Tarleton turned his column onto the main road to Salisbury. As they marched along heavy rains fell making the roads very difficult for the infantry. After traveling about 5 miles Tarleton stopped and told the 23rd to wait. He then rode ahead with only the Legion dragoons. They had gone a short distance when Tarleton learned that rebel militia from Rohan and Mecklenburg counties were meeting at Tarrant’s (or Torrence’s) Tavern about three miles further down the road. The dragoons hurried forward as Tarleton sensed opportunity to make a dramatic impact on the rebel militia of North Carolina. As they approached the tavern Tarleton noted,” the militia were vigilant, and were prepared for an attack.”[xvi]

The Legion dragoons advanced slowly until a proper position was reached. Tarleton then gave them a brief speech that culminated with “remember the cowpens”. The Regiment broke into a furious charge directly through the center of the rebel positions. Tarleton described the charge as having “irresistible velocity” claiming to have killed 50 men “on the spot” and wounding many others in the chase. Over 500 rebels were dispersed into the area. The dragoons broke into small groups and “diffused such a terror among the inhabitants, that the Kings troops passed through the most hostile part of North Carolina without a shot from the militia.” Tarleton gives his losses at seven men killed and wounded with the loss of 20 horses, all from the first rebel fire.[xvii]

As with the previous battles of Cowpens and Blackstocks, Tarleton’s account of the skirmish at Tarrant’s Tavern differs significantly from the main rebel account. General Joseph Graham’s narrative set down after the war includes a very different description of the events. He says a large group of refugees and militia from Beattie’s Ford and Cowan’s Ford converged somewhat haphazardly at Torrence’s Tavern. The group, “Being wet, cold and hungry, they begin to drink spirits, carrying it out in pails full. The wagons of many of the movers with their property were in the Lane, the armed men all out of order, and mixed with the wagons and people, so that the Lane could scarcely be passed, when the sound of alarm was given from the West End of the Lane” Tarleton is coming.” Though none had had time to become intoxicated, it was difficult to decide what course to pursue in such a crisis.”[xviii]

Of the rebel preparedness Graham says that Capt. Nathaniel K Martin “and six or eight others (our Ms. Cavalry) rode up meeting the enemy, and called to the men to get over the fences and turn facing the enemy.” Capt. Martin had only limited success as” some appeared disposed to do so”. Unfortunately, most of the men started moving off, “some with their pails of whiskey.” At that point one of the Legion dragoons shot down Capt. Martin’s horse. He was quickly taken prisoner while the Legion charged through the crowded Lane. Joseph Graham says only 10 men were killed and that number included a few unarmed old men who just happened to be at the tavern looking for news.[xix]

In Tarleton’s account there is no mention of any post-battle activities other than rounding up some prisoners. Joseph Graham tells us the dragoons engaged in systematic plundering as they regrouped from pursuit. “They made great destruction of the property in the wagons of those who were moving; ripped up beds and strode the feathers, until the Lane was covered with them. Every thing else they could destroy was used in the same manner.”[xx]

Joseph Graham’s account of the situation at Tarrant’s is supported by others. In the pension application for John Baldridge, his widow, Isabella, said this about the actions at Tarrant’s Tavern. “He was in the battle at Cowan’s & Beattie’s Ford in North Carolina under General Davidson, who was killed in the engagement and the American army was forced to retreat; Affiant’s husband came to where she was after the retreat and procured horses and carried he off into a remote & less dangerous portion of North Carolina and left for his Company & post in the army, and he was so closely pursued by Cornwallis that she once in flight had a full view of the British army. That the British took their wagon, horses and all their plunder, they afterwards recovered the wagon, but nothing else * *”[xxi] Not only do we see rebel accusations of plundering by the British Legion that day, but also find Cornwallis reacting to it very strongly both that afternoon and also three days later. Cornwallis was “highly displeased that several houses was set on fire during the March this day.” He threatened punishment “of the utmost severity any person * * * guilty of committing so disgraceful an outrage.” The timing of Lord Cornwallis’s outbursts strongly suggests anger at Legion plundering after Tarrant’s Tavern.[xxii]

As for Tarleton’s claim of having killed 50 rebels on the first charge, Cornwallis seems to think the claim overstated. Only 3 days after the action he told Lord Rawdon that the Legion “killed several, took some prisoners, and dispersed the rest.”[xxiii] A month later, Cornwallis reported back to Germain the loss on rebel side was “between 40 and 50 killed, wounded, and prisoners.”[xxiv] One explanation for Cornwallis’s more conservative view comes from the Loyalist, Charles Stedman, who observed that “a British officer who rode over the ground not long after the action, relates, that he did not see ten bodies of the provincials in the whole.”[xxv] However, at least one British author supported Tarleton’s claim. In his book, Sgt. Lamb indicated 500 rebels were “prepared to receive him, who were immediately charged, their centre broken through, fifty killed and the rest dispersed.”[xxvi] The problem is that, even though Lamb was with the 23rd regiment waiting just 5 miles away from Tarrant’s, his account adds nothing but a brief summary of the Tarleton account.

There is one point upon which all of the British authors seem to agree. Tarleton made a serious impact upon the population of North Carolina. In his report to Germain, Cornwallis concluded that, ” this stroke with our passage of the Ford so effectually dispirited the militia that we met with no further opposition on our march to the Yadkin through one of the most rebellious tracks in America.”[xxvii] Sgt. Lamb said, “the gallantry of these actions made such an impression on the inhabitants that the troops made their way without molestation to the Yadkin, notwithstanding the inveterate prejudice upon which this part of North Carolina board to the British name.”[xxviii] Stedman seems to be part of Lamb’s inspiration. He described Tarleton’s impact as “such an impression upon the inhabitants, that although the country between the Catawba and the Yadkin was deemed the most hostile part of North Carolina, the Army in its progress to the last of these rivers met with no further molestation by the militia.”[xxix] Tarleton himself summarized the impact of Tarrant’s Tavern in a very similar manner. “This exertion of the cavalry succeeding the gallant action of the guards in the morning, diffused such a terror among the inhabitants, that the King’s troops passed through the most hostile part of North Carolina without a shot from the militia.”[xxx]

In truth, Lord Cornwallis’s reaction to all of the plundering seems inconsistent with his praise for the effect the action at Tarrant’s Tavern had on putting down local opposition. However, if one considers that his mission involves not only chasing Greene’s army but also the reestablishment of British rule, the problem facing Cornwallis becomes apparent. Cornwallis needed to walk a delicate tightrope between demonstrating total authority without hardening the opposition by demonstrating the absolute worst side of ’British tyranny’. Turning Tarleton loose to have his revenge on the people of North Carolina did nothing to aid the British cause of returning them to loyal status. North Carolina knew very well the people of South Carolina and Georgia had run off a string of victories against Ferguson and Tarleton that had the British occupation force stuck in their garrisons. Chopping up a train of refugees only added more fuel to an already burning situation. There would be no significant portion of the North Carolina population turning out to fight for the British against their Patriot neighbors.

[vii] General Joseph Graham’s Narrative of the Revolutionary War in North Carolina in 1780 and 1781, Joseph Graham, printed in the Papers of Archibald D. Murphey, Vol 2, William Henry Holt, 258

[ix] An Original and Authentic Journal of Occurrences During the Late American War: From Its Commencement to the Year 1783, Roger Lamb, 343

[xi]An Original and Authentic Journal of Occurrences During the Late American War: From Its Commencement to the Year 1783, Roger Lamb, 344

[xiii] State of Troops fit for duty, 15 January to 1st April 1781, The Cornwallis Papers, Vol 4, Ian Saberton, 61

[xviii] General Joseph Graham’s Narrative of the Revolutionary war in North Carolina in 1780 and 1781, The Papers of Archibald D. Murphey, Vol 2, Joseph Graham, 263

[xix] General Joseph Graham’s Narrative of the Revolutionary War in North Carolina in 1780 and 1781, The Papers of Archibald D. Murphey, Vol 2, Joseph Graham, 263

[xx] General Joseph Graham’s Narrative of the Revolutionary War in North Carolina in 1780 and 1781, The Papers of Archibald D. Murphey, Vol 2, Joseph Graham, 263

[xxii] Long Obstinate & Bloody the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Babbits and Howard, 24, quoting Cornwallis from “British Orderly Book”, Newsome

[xxiii] Cornwallis to Rawdon, February 4, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, Vol 4, Ian Saberton, 44

[xxiv] Cornwallis to Germain, March 17, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, Vol 4, Ian Saberton, 14

[xxv] A History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War, Charles Stedman, 330

[xxvi] An Original and Authentic Journal of Occurrences During the Late American War: From its Commencement to the Year 1783, Roger Lamb, 345

[xxvii] Cornwallis to Germain, March 17, 1781, the Cornwallis papers, Vol 4, Ian Saberton, 14

[xxviii] An Original and Authentic Journal of Occurrences During the Late American War: From its Commencement to the Year 1783, Roger Lamb, 346

[xxix] A History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War, Charles Stedman, 330

[xxx] a history of the campaigns of 1780 in 1781, Banistre Tarleton, 233

4 Comments

Mr. Lynch: With respect, the tavern was called Torrence’s Tavern. The owner was my direct relative plus the state of North Carolina has a State History Highway marker (North of Davidson, N.C.) also stating it was known as Torrence’s Tavern where Tarleton’s cavalry attacked.

Naturally I wouldn’t argue with family and I recognize the right of a man to spell his name as he pleases, however, in my research, the name Tarrant’s and the name Torrence both appeared regularly. almost interchangeably. In the article above, you will see the same treatment. The first place the name appears in the body, the place is referred as “Tarrent’s (or Torrence’s)”. As you read on through, you will note the pattern of changing from one to the other continues. In light of your comment, the next time I write about the incident at Torrence’s Tavern, I hope to remember to say it as ‘Torrence’s (or Tarrant’s)’.

Thanks very much for stopping by. You bring out an interesting point regarding names. We see different spellings in historical writing on a regular basis and I often wonder about just exactly which spelling should govern. I personally have an ancestor from the southern campaigns named Stephen Dusenberry, or Dusenbury, or Dewsunbery, etc. on any given day. He certainly made searching in various indexes an interesting concept.

I have recently been involved with researching a fellow named Grierson in Augusta, Georgia. Been great fun searching the various sources for a fellow named Grayson. 🙂

Dear Mr. Lynch:

I am a DAR of 32 years and I have been researching my father’s direct line of McClendons for about 6 years. My 4-G-Grandfather Isaac McClendon was a Rev. War soldier but I am having trouble locating his specific service. He has been confused over the years by DAR and others with his first cousin Isaac McClendon (b. 1750 and who married Elizabeth Stribbling) but the two Isaac’s were very different individuals. My Isaac was born in North Carolina in 1754 so at the start of the war he would have just turned 21 in 1775. Although I cannot find evidence of him as a property owner/tax payer, I know from his prior generation history that his father was in Craven/Johnston County when he was born, then his father moved to Cumberland County in 1764. Isaac received a pay voucher for his services in the NC Militia through the Wilmington District in 1781. He also received 3 bounty land grants in Washington County, GA in 1783+ from Elijah Clarke. I have studied the history of the Cumberland and Montgomery County, NC areas and it was a war corridor on a regular basis, as you know. The McClendons lived on McClendons (Buck) Creek where they were neighbors with the McDonalds, McIlweans etc., and his father later sold his property to Martin so I believe they were involved with Moore’s Creek but can’t prove it. I have also read a biography of Elijah Clarke and he resided in that general area and most likely mustered men to join his cause that included joining Greene, Pickens, etc., at Cowpens, Kettle Creek, Blackstocks Farm and possibly Charleston. If he was in Cumberland county, he would have been in the Salisbury District but I found that the militia in Salisbury was commissioned to secure and free Wilmington from the British siege so they were most likely paid from the Wilmington payroll. The problem? I can’t find exactly who he fought under. I have searched NARA by looking under the commanders but it is difficult. I have successfully searched the entire listings on Carolana.org and did not locate him. I have also read that the NC Militia frequently fought and assisted in Pennsylvania, which would explain his marriage to Mary Fincher occurring in Philadelphia. Mary’s family lived in neighboring Mecklenberg County, NC, and when the men began engaged in the war, I am theorizing that her father sent her (the women) back to Philadelphia where the Fincher clan resided when the war got volatile in the Cross Creek area (Tarleton’s raids) so that she would be safe (the distance of travel was too great to justify a wedding when her immediate family and Isaac’s family lived in Mecklenberg/Montgomery Co NC). So how else can I research his actual service? He ultimately became an attorney and Judge of the Inferior Court for Jasper County, GA, and was a respectable and family man. With your extensive historical background, do you have any suggestions? With my enormous delving, I have learned wonderful things about my father’s line but cannot crack this mystery! Isaac seems to be in between the cracks. Can you help?

Ms Novarro, thanks for the comment and question. Unfortunately, I poked around and found no mention of Isaac in the Georgia militia sources (Elijah Clarke) or the militia sources done by Bobby Gilmer Moss on South Carolina Patriots. I also checked the pension files although I imagined that was probably already covered since you have been looking for quite a few years now. I find the land grants from Elijah Clarke particularly interesting. Elijah moved to the GA Ceded Lands just before the war broke out. Is there any indication that Isaac had moved there with him? I have some prior work on Elijah and am currently doing some expansion of that work but I don’t remember running across Isaac’s name. In truth, my focus isn’t really pulling out names as much as finding the stories to be told about the southern partisans. Because of that, I really don’t have many genealogical sources. The library I go to for Draper microfilm has a large collection, perhaps they can help. The Clayton Library in Houston.

For Salisbury militia regiments, you might look into the narrative of General Joseph Graham. He may have been with the regiments you are looking for. It can be found in the 2nd volume of the Papers of Archibald Murphy and I think it may also be in the State Records of North Carolina series. Many militia regiments in the southern campaign had rather fluid rosters as men pretty much came and went at will. Certainly the Georgia Refugees who fought under Elijah Clarke carried such a distinction. In fact, they also had some time fighting alongside Joseph Graham’s men. During Greene’s North Carolina campaign prior to Guilford Courthouse. Both groups were part of the militia regiments who left Greene after Wetzel’s Mill. That time period could provide you with a crossover with Elijah Clarke’s men. (Elijah himself was not with them having been badly wounded during the Long Canes uprising in December 1780.)