Every historical researcher, and readers of history books and magazines, must constantly keep in mind the power of the written word. Whether reading for pleasure or serious study one constantly weighs the evidence to determine whether it is accurate and credible or not.

Every historical researcher, and readers of history books and magazines, must constantly keep in mind the power of the written word. Whether reading for pleasure or serious study one constantly weighs the evidence to determine whether it is accurate and credible or not.

Regrettably, the written word itself attaches credibility to a statement by the mere fact it appears in print. Unless one is on guard one tends to docilely accept what appears on the page with no other evidence of its veracity than its very existence in print. It is vital to know the source of the information so one can check the facts and also so one can judge how much confidence ought to be placed on the information.

An extreme example would be the hypothetical case of George Washington’s axe. “This is George Washington’s axe. Due to its historical significance the axe-head and handle were replaced during the restoration process.” Is it really George Washington’s axe? With the head and handle both replaced how can it possibly still be George Washington’s axe. Rarely however is the lack of common sense, or proper documentation, so obvious.

An example of the powerful influence of the written word is the legend of Timothy Murphy. Murphy is widely credited, and has been for generations, with having shot British Brigadier General Simon Fraser at the battle of Saratoga in 1777. Respected historians have accepted the Tim Murphy tale as fact based on literally nothing but that it has been repeated, in print, by others for 150 years. However, an analysis of the origins and source of the story make it very clear that the story of Murphy is not based on fact.

The basics of the story are that during the battle Tim Murphy, a rifleman serving under Colonel Daniel Morgan, was ordered by Morgan to shoot Brigadier General Simon Fraser. Depending upon which version of the story is related Murphy may have fired more than once with each shot getting ever nearer to Fraser. He possibly fired from a tree and possibly used a double barreled rifle.

An abbreviated chronology of the various accounts of the shooting of Fraser sheds light on the origins of the legend of Tim Murphy. The Saratoga Sentinel newspaper published a letter on 10 November 1835, fifty eight years after the battle, from one Ebenezer Mattoon a veteran of Saratoga. Mattoon relates that he witnessed an unnamed “elderly man, with a long hunting gun….” on the battlefield. Through a break in the powder smoke of the battle “several officers, led by a general, appeared moving to the northward, in rear of the Hessian line. The old man, at that instant, discharged his gun, and the general officer pitched forward on the neck of his horse….”[1]

The next published account of the shooting appeared in Jeptha R. Simms’ 1845 History of Schoharie County and Border Wars of New York. Sixty eight years had elapsed since the battle, and twenty seven years since Timothy Murphy’s 1818 death in Schoharie County, New York. This account, as far as can be determined, marks the first time the name Timothy Murphy is connected with the shooting of Fraser. Simms writes that Daniel Morgan “selected a few of his best marksmen” and “instructed to make Fraser their especial mark… Timothy Murphy… was one of the riflemen selected.” As Fraser came into range each had “a chance to fire, and some of them more than once, before a favorable opportunity presented for Murphy; but when it did, the effect was soon manifest. The gallant general was riding upon a gallop when he received the fatal ball, and after a few bounds of his charger, fell mortally wounded.” Simms writes that “the fact that Murphy shot Gen. Fraser, was communicated to the writer by a son of the former.” However, Simms does not supply the name of the son, when or how the son learned of the story, or any other information surrounding the event or Murphy’s retelling of it. In the book’s preface Simms writes that he began his research in 1837 from “the lips of many hoary-headed persons of intelligence then living, whom I visited at their dwellings.” The unnamed son of Timothy Murphy may have been one of these people.[2]

Two years later one N.C. Brooks wrote a magazine article naming Murphy and adding information about the weapon without citing a source.[3]

In 1853, a letter dated 28 November 1781, four years after the battle, written by British officer Joseph Graham (not to be confused with James Graham, a biographer of Daniel Morgan) was published in the Virginia Historical Register. Joseph Graham had been taken prisoner by the Patriots and claims to have spoken with Morgan. He wrote that Morgan described the shooting of Fraser, without mentioning any rifleman’s name:

“I saw that they were led by an officer on a grey horse – a devilish brave fellow; so, when we took the height a second time, says I to one of my best shots, says I, you get up into that there tree, and single out him on the white horse. Dang it, ‘twas no sooner said than done. On came the British again, with the grey horseman leading; but his career was short enough this time. I jist tuck my eyes off him for a moment, when I turned them to the place where he had been – pooh, he was gone!”[4]

James Graham wrote The Life of General Daniel Morgan of the Virginia Line of the Army of the United States in 1856. As James Graham had married one of Morgan’s great -granddaughters he had access to oral family history as well as Morgan’s papers. Without referencing a source he relates that Morgan selected “twelve of his best marksmen” and that Morgan “pointed out the doomed officer.” Graham wrote that Morgan “anxiously observed his marksmen, when, a few minutes having elapsed, and Fraser re-appearing within gun-shot of them, he saw them all raise their rifles and, taking deliberate aim, fire.” Timothy Murphy is not named nor is any other rifleman named.[5]

In 1877 William L. Stone published The Campaign of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne and the Expedition of Lieut. Col. Barry St. Leger. Stone mentions the shooting of Fraser several times in this volume. He quotes a letter dated 31 October 1827, written by Samuel Woodruff, Esq., of Windsor, Connecticut. Woodruff, who apparently participated in the battle, visited the battlefield on October 17, 1827 and wrote a description of Morgan ordering “his riflemen” to specifically target General Fraser. Woodruff continued, “…the crupper of the grey horse was cut off by a rifle bullet, and within the next minute another passed through the horse’s mane, a little back of his ears. An aid [sic] of Fraser noticing this, observed to him, ‘Sir, it is evident that you are marked out for particular aim; would it not be prudent for you to retire from this place?’ Fraser replied, ‘my duty forbids me to fly from danger,’ and immediately received a bullet through his body.” Woodruff does not indicate a source of this information nor mention any rifleman’s name.[6]

In the same book Stone repeats the Fraser story twice more and identifies the rifleman as Timothy Murphy. In the first instance, Stone writes that Morgan “took a few of his sharpshooters aside, among whom was the celebrated marksman Tim Murphy, men on whose precision of aim he could rely, …” Stone, using almost the exact wording as Samuel Woodruff but inserting Murphy’s name, continued, “Within a few moments a rifle ball cut the crouper of Fraser’s horse, and another passed through his horse’s mane. Calling his attention to this, Fraser’s aide said, ‘It is evident that you are marked out for particular aim; would it not be prudent for you to retire from this place?’ Fraser replied, ‘my duty forbids me to fly from danger.’ The next moment he fell mortally wounded by a ball from the rifle of Murphy.”[7]

In the same volume, Stone quotes one Charles Neilson, whose father served at Saratoga, as saying, “The soldier who shot General Fraser was Timothy Murphy, a Virginian, who belonged to Morgan’s rifle corps.” Neilson provides no source that names Murphy as the marksman.[8]

Stone also discusses the Mattoon version of the shooting, and appends a footnote stating, “Still, there seems no doubt that Murphy, by the orders of Morgan, shot Fraser; see Silliman’s visit in the Appendix where he speaks of Morgan having told his friend, Hon. Richard Brent, to this effect.”[9]

The Appendix contains the account of Benjamin Silliman’s visit to the battlefield in 1820. It reads, “The following anecdote, related to me at Ballston Springs, in 1797, by the Hon. Richard Brent, then a member of Congress, from Virginia, who derived the fact from General Morgan’s own mouth.”

“Colonel Morgan took a few of his best riflemen aside; men in whose fidelity, and fatal precision of aim, he could repose the most perfect confidence, and said to them: ‘that gallant officer is General Fraser; I admire and respect him, but it is necessary that he should die – take your stations in that wood and do your duty.’ Within a few moments General Fraser fell, mortally wounded.”[10]

Incredibly, despite Stone’s assurance that Silliman’s comments in the Appendix would specifically name Timothy Murphy, it does not. Murphy is not named at all, nor is any other rifleman.

Jeptha Simms’ History of Schoharie County, apparently based on an interview with a son of Murphy an indeterminate number of years after the event, is the only account prior to 1877 to name Murphy as the rifleman who shot Fraser. However, Stone repeats it as historical fact ignoring other accounts that do not name an individual.

In 1883, Simms wrote a follow-up book, The Frontiersmen of New York Showing Customs of the Indians, Vicissitudes of Pioneer White Settlers, and Border Strife in Two Wars, Wtih a Great Variety of Romantic and Thrilling Stories Never Before Published. The shooting of Fraser is retold in the now customary manner, with Simms adding two unnamed Murphy daughters plus an unnamed Murphy son as original sources.[11]

In 1895, William L. Stone published a follow-up book of his own, Visits to the Saratoga Battle-grounds, 1780-1880, claiming that Murphy himself was positive he shot Fraser. He offers no evidence to support this claim.[12]

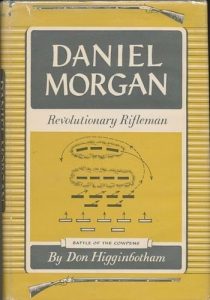

Noted historian Don Higginbotham, wrote the well received biography of Morgan, Daniel Morgan, Revolutionary Rifleman, in 1961. He describes Murphy’s weapon as a double-barrel rifle. Higginbotham erroneously wrote that, “Morgan told Graham of the shooting of General Frazer by his rifleman Timothy Murphy,” when in fact Graham did not mention any rifleman by name. Higginbotham quotes Graham but inexplicably inserts Murphy’s name in brackets: “Says I to one of my best shots [Murphy], says I, you get up into that there tree…”[13]

Noted historian Don Higginbotham, wrote the well received biography of Morgan, Daniel Morgan, Revolutionary Rifleman, in 1961. He describes Murphy’s weapon as a double-barrel rifle. Higginbotham erroneously wrote that, “Morgan told Graham of the shooting of General Frazer by his rifleman Timothy Murphy,” when in fact Graham did not mention any rifleman by name. Higginbotham quotes Graham but inexplicably inserts Murphy’s name in brackets: “Says I to one of my best shots [Murphy], says I, you get up into that there tree…”[13]

In the 150 years since Jeptha Simms wrote his History of Schoharie County many, if not most, accounts of Saratoga and Revolutionary War marksmanship have included the story of Timothy Murphy. Based on nothing more than its having appeared in print so often in the past the story continues to be published. Most regrettably, it has been published by many who ought to know better.

Timothy Murphy was a real man. He was a rifleman under Morgan at Saratoga. However, the story of his shooting of Fraser, like the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, is not history. The real story of Timothy Murphy is the story of the power of the written word.

Editor’s note. This article edited for length and content. For full details plus an analysis of the ballistics of long range musket and rifle fire see The Journal of Military History, vol. 74, No. 4, October 2010, page 1037-1045, “The Other Mystery Shot of the American Revolution: Did Timothy Murphy Kill British Brigadier General Simon Fraser at Saratoga?” by Hugh T. Harrington and Jim Jordan.

[1] Ebenezer Mattoon letter published in Saratoga Sentinel, 10 November 1835, reprinted in The Campaign of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne and the Expedition of Lieut. Col. Barry St. Leger, by William L. Stone, Albany, NY, Joel Munsell publisher, 1877, reprinted, New York, Da Capo Press, 1970, p. 369-74.

[2] Jeptha R. Simms, History of Schoharie County and Border Wars of New York, Albany, NY, 1845, reprinted Bowie, MD, Heritage Books, 1991, p. v and 259.

[4] Joseph Graham, “A Recollection of the American Revolutionary War,” Virginia Historical Register, vol. 6 (1853), p. 209-211.

[5] James Graham, The Life of General Daniel Morgan of the Virginia Line of the Army of the United States, New York, Derby & Jackson, 1856, reprint, Bloomingburg, NY, Zebrowski Historical Services Publishing Company, 1993, p. 162-63.

[6] William L. Stone, The Campaign of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne and the Expedition of Lieut. Col. Barry St. Leger, Albany, NY, Joel Munsell publisher, 1877, reprinted, New York Da Capo Press, 1970, p. 324-27.

[11] Jeptha R. Simms, The Frontiersmen of New York Showing Customs of the Indians, Vicissitudes of the Pioneer White Settlers, and Border Strife in Two Wars, With a Great Variety of Romantic and Thrilling Stories Never Before Published, vol. 2, Albany, NY, George C. Riggs, Publisher, 1883, p. 126.

39 Comments

Thank you for addressing this popular tale. Perhaps you can devote some time to two other sharpshooter myths, that of Peter Salem killing Major John Pitcairn at the battle of Bunker Hill; and of Hans Boyer killing Brigadier James Agnew at the battle of Germantown.

Ah! These two myths deserve attention. Sounds like a challenge I may not be able to resist.

Very interesting. Once you go to source documents in is amazing how lore intermingles with fact. Were there any mentions of the sniping of General Fraser in Aaron Wright’s diary? I’m not sure if he followed Tim Murphy to Morgan’s Sharpshooters after he served with Captain John Lowdon’s Company of Northumberland County Riflemen. Since Murphy could not read or write we can only speculate what he did through proxies. I climbed Vorman’s Nose in Schoharie County three days ago and I will tell you that the legand of Tim Murphy is still very strong there!

Aaron Wright’s diary only goes from June 1775 to March 1776. Therefore, he does not mention Murphy at Saratoga. I too have been to Schoharie County…the myth is indeed alive and well.

There can be no doubt regarding the correctness of Hugh Harrington’s analysis of the Timothy Murphy myth. It would be good if he would go to Wikipedia and correct the entries there. Someone should because this myth seems to be a particularly difficult one to kill.

All myths are particularly difficult to kill. If you want to kick over a hornet’s nest see “Black Confederate Soldier” myth in any Civil War (War of the Rebellion) blog

Or, more appropriate for this site, the famous John Adams quote about the Revolution: one third for it, one third against it, one third didn’t care. He never said it, see Paul H. Smith William & Mary quarterly, April 1968.

Excellent scholarship. It’s amazing how a half truth can become a lie and then a historical fact with such ease.

Thank you, Simon. The ease which fiction becomes historical fact is not just amazing it is rather scary. Since Murphy I find myself constantly double checking sources – and, if a “fact” comes from a secondary source I try to find where the secondary source writer got the information. In the long run if we all keep alert we can better weed out the fiction and become better historians.

Indeed; I always double check and make use of the bibliographies (a wonderful tool that I’m amazed so many people simply overlook). I’m just getting ‘into’ the Revolutionary period. I’m afraid I come from the Other Side and so… well, let’s just say I’m rooting for the other chaps!

Simon, welcome aboard. It’s a great adventure. Since you’re new to the revolutionary period I won’t tell you how it turns out. 🙂 I not only scrutinize bibliographies but I’m an avid reader of footnotes/endnotes.

Ha ha spoiler alert 🙂

I thanks Simon and Hugh for this thread. The book I’m working on now makes no effort to take sides at Saratoga. This is easy because apart from the Germans there was a common language that facilitated polite conversation when the men were not busy trying to kill one another. It is difficult to find evil in the main events that unfolded there. I find that I often come away from a day of reading and writing with a sense of the American Revolutionary War as a human tragedy, and it is that sense of the tragic and the inevitable that keeps drawing me back to the subject.

Good luck with your book; it seems a crowded field but well worth reappraising. For example, I was just going through ‘Saratoga’ by Ketchum, R. (Henry Holt & Co, 1997). It’s a great work, but it also cites the Murphy story (p.400) as fact, showing just how entrenched this particular tale is. That’s why I was grateful for Hugh’s work in taking a sharp scholarly axe to this particular facade.

With the Saratoga campaign I find the two commanders fascinating for their flaws. But for all his faults, at least “Gentleman Johnny” was brave and, when the manure hit the Saratoga-shaped fan, stood and took the risk with his men.

With Gates, I’m really just not so sure. It’s hard to be objective but I’m reminded of a chateau general. On p407, Ketchum also details his rather unsavoury effort to argue the ideals of the Revolution with a dying officer, Sir Francis Carr Clerke. However, this is based on Wilkinson’s recollection of events.

I agree with your thoughts on the tragedy of it all; the grave error really boiling down to the pig-headed belief that sovereignty rests with Parliament and the crown. I read an excellent appraisal (my mad-cow memory means I’ve forgotten who wrote it) viewing the American Revolution through the prism of being another English civil war.

S

Thanks Dean. I look forward to your book. Glad to hear that you keep being drawn back to the revolution.

I’m an archaeologist who has worked in the NY Capital region for 20 years, and I’m compelled to comment that shameful sensationalist journalism such as this should not be passed off as an honest historical critique. Notably, your presentation of Timothy Murphy is minimalist, leaving uninformed readers to infer that he was just “some yokel” from Schoharie, when in fact Murphy was among the most prominent and respected frontiersman, indian fighters, and sharpshooters of his day. The incident at Saratoga was a mere footnote in his career. In fact, Murphy had a double barreled rifle made so he could shoot twice without reloading. The rifle is currently housed in Schoharie’s “old Stone Fort Museum”.

Now the article cites a number of sources in agreement that Morgan selected a group of the best sharpshoters and one of them shot Fraser. Jeptha Simms – whose work is highly valued and useful to local historians and archaeologist – presents an almost identical narrative, save that the shooter is identified through family oral history (immediate children) to have been Timothy Murphy. It is entirely likely that a man like Murphy, who was certainly present at Saratoga, would have been one of the sharpshooters chosen by Morgan. Of course I agree there is no proof that Murphy really was the one who shot Fraser, and that is a caveat that should never be forgotten, but Simms account should be not be taken so flippantly since it is perfectly plausible and at least partially corroborated. It is certainly not something a responsible historian should sneer at as mere falsehood and “myth”.

20 years? What have you published of your work?

Maybe you should get over it since history should be investigated with solid facts. Timothy Murphy probably wasn’t there since in research his military papers never mention Saratoga

REVEREND Daniel Boggs!!!!!

I think we can all agree that Morgan ordered General Fraser to be taken out. Whether the task was given to Murphy alone or a group of sharpshooters is of no relevance at this point. This event is not disputed and is historically significant enough that we should know who fired the shot. Can any of you give me any other name that might have been responsible? No you can’t. The only name ever associated with this event is Timothy Murphy. I agree, this was a battlefield, and there is no way to ever know 100% whose bullet struck the target. But Murphy was there and given the assignment and it was executed. I can see it now, ‘high fives’ and cheers for ‘Ole Murph’. He was given credit then so why try and take it now? He is named in this article but not in that one. So what? Journalism in the 18th century was not the same as it is today. Seems to me that people are trying to detract from an honorable figure and focus the attention on themselves. That is truly shameful to a true American Patriot!

Too bad. He wasn’t there. I see the monuments to him at the Saratoga battlefield. I used to believe in them but doing research with maps you find out that some are false. One even labels the wrong ravine!

I find it annoying that the writers of these books were using their counterparts sources. The sole base of fact are primary sources that can be verified. If not then there is no proof and should be labeled as such. Dummy

Critchlow.

There is no evidence that Tim Murphy fired on Fraser. None. He was NOT known during his lifetime as the man who shot Fraser. In her widow’s pension application Murphy’s wife did not mention he shot Fraser – she did not even mention he was at Saratoga. Sorry to disappoint but the story of Tim Murphy is a myth.

This was a wonderful read. As a librarian and lover of the Revolutionary War, it was right up my alley. Have you come across anything in your research about Timothy Murphy not originally being “Timothy Murphy,” but being a member of the Baskins family who was captured by Indians and renamed?

I’m delighted that you enjoyed the article, Samantha. I’m sorry but I know nothing about anything relating to the Baskins family and Timothy Murphy. The “captured by Indians and renamed” sounds suspicious to me, however. I’d certainly want to find some primary sources to confirm that. Thank you for taking the time to comment on the article.

What is Saratoga National Park’s view of Timothy Murphy shooting Fraser?

While there are old monuments to Murphy at Saratoga it is generally acknowledged that the story of Murphy is a fabrication not based on fact.

Is singling a man out and killing him something to be proud of. Was that something that was thought of as being “less than gentlemanly”? Maybe it’s something you don’t brag about. I don’t really care one way or the other. Just wondering. Also, you can say Tim Murphy didn’t kill Simon Fraser, based on claims made years after the war. But if you take all the claims out, you are left with an unknown soldier who killed him. Maybe the unknown soldier was Tim Murphy.

Jon B., I would agree with you that the bullet that killed Fraser could have come from almost literally any soldier. The point is that the case for Murphy being the shooter is a case a very poor “history” and its acceptance into the realm of fact based merely on its many decades of repetition. John F. Luzader in his excellent “Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution” (New York, Savas Beatie, 2010, xxii) writes, “Nineteenth century writers, upon no contemporary evidence, attributed his [Fraser] death to rifleman Timothy Murphy, a man who, on the basis of his widow’s pension application, was not even present at Saratoga.” Perhaps, Murphy ought to be eliminated from the huge pool of possible soldiers.

Fair enough. I don’t know if Murphy is “the guy” or not. I guess I’d like him to be. I like legends. I like heroes.

This would be Murphy’s “second” wife who filed the pension application. They were married a full 30 years after the end of the war. Did she really know his war service? Did she get the rest of his service right? Maybe Murphy wasn’t interested in people knowing what he did. Maybe it was him just doing his job. Maybe his son hopped up on his knee one day and asked him what he did in the war. Maybe Murphy lied. Maybe he didn’t. Maybe if Murphy was literate, like Joseph Plumb Martin, he would have written something. Would we believe him then?

I do remember an historian commenting on Gen. John Buford’s performance during the first day at Gettysburg. By engaging and slowing the Confederates west and north of town, it saved the heights south of town for the Union army to occupy. Because Buford never stated specifically that he was trying to keep the Confederates from said ground, this historian believed Buford was given credit for something that he didn’t deserve.

It’s ok to have these legends. It’s ok to believe Tim Murphy killed Simon Fraser.

The mythos of a marksman singling out a key British office and picking him off grew up in the early 19th century. Major Pitcairn at Bunker Hill, General Fraser at Saratoga, General Agnew at Germantown – for each one, there’s an apocryphal story of a heroic sharpshooter who made the fatal shot. And yet, at the time each event occurred, and for a few decades afterwards, no one seemed interested in giving such individual credit. Battle casualties were, for the most part, collective effects rather than the work of an individual. For some reason, subsequent generations weren’t satisfied with this, and created legends of individual heroes rather than collaborative accomplishments.

Keep in mind the context of the times when these accounts were written. There was no need for heroes in the couple of decades following the close of the war, but that all began to change around 1800, and accelerated after the War of 1812 when America was finally coming into its own. This was when towns, cities, and states trying to distinguish themselves from the rest began to sift through their own historical records to find those individuals and events that would show they were special. It was also the starting point for the many historical societies and organizations around the country, and was also a contributing factor to the worldwide nationalism movement.

There are plenty of these stories from the period (19th Century) in both the Revolution and then the Civil War. Besides the incidents mentioned above there exists a very popular story in Connecticut during Arnold’s raid on New London where a local women named Abigail Hinman attempted to shoot Arnold when he rode past her house. I’ve found at least 3 different versions of the story and they all contradict each other. The gun misfired in one , the next it wasn’t even loaded, Arnold saw her, Arnold didn’t see her, she hid behind a window, she was out in the open. No contemporary evidence, yet it got very cool painting and very historically inaccurate engraving.

During the Civil War, specifically at the Battle of Gettysburg with the shooting of Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, you get a story a lot like the Tim Murphy-General Fraser story. Reynolds was supposedly killed by a sharpshooter during the first day of the battle. I’ve heard multiple versions of how a sharpshooter hid in a tree, hid in barn, was from Alabama, was from Tennessee and so on. Like Murphy-Fraser I don’t think you’ll ever know who shot who. Such is the chaos of combat.

Greatly enjoyed this article. I grew up near the battlefield and have over the last 10 years done extensive reading. I recently began to read the Specht journal who was one of the German officers present. Online I have found a wealth of journals and letters written by officers during the Burgoyne campaign. All excellent reads and opens more on what the daily life was like for these troops. I also have spent time at the Stillwater years ago organizing their files. I had the chance to read some of their sources and found out more about disagreements on the layout of the american situaion at Neilson farm.

I never knew so much information was out there on this moment in history. I was ignorant how many actually wrote down their experiences. I will continue to learn about what happened in my back yard!

I for one welcome this refutation of one chapter in the Timothy Murphy myth. I know he’s celebrated as a hero in his home territory — and that then-Governor Roosevelt praised Murphy at the Saratoga Battlefield monument dedication in 1929, but the mythological Murphy is not the kind of hero that our nation needs. In 1777, to single out and target an officer of high rank in fine uniform on a splendid mount was far beyond bad military protocol; it was plain and simple murder, orders or no orders. 1779 finds the mythological Murphy accompanying the Sullivan campaign into the westernmost reaches of upstate New York, where Lt. Thomas Boyd recruits him on a scouting mission which ends in disaster. On that scout, Murphy disobeys Sullivan’s explicit order to not engage the enemy, firing on a party of three Senecas, killing one and taking his scalp which is added to an already extensive collection. That murder seems to have been a factor when the Boyd party stumbles into an army of several hundred Indians and Butler’s Rangers who have been awaiting the opportunity to bother Sullivan’s flank. Two allied Indians and 16 American solders die in the ambush. The next day Boyd dies at the stake. Murphy and a handful of others somehow escape. One year later, Murphy is in Schoharie County manning the wall of Fort Defiance while John Johnson and his raiders are setting the valley ablaze and demanding surrender of the fort. In one version of the myth, Murphy fires over the head of the small party of approaching loyalists proposing a truce, causing them to flee. In another version, he shoots one dead. Murphy then threatens his commanding officer, Major Woosley, with death if he attempts to strike a white flag. Woosley is intimidated into hiding. Johnson, having just tiny artillery, is unable to penetrate the fort and eventually retreats, whereupon Murphy is declared the hero of the hour. Murphy’s true involvement with Boyd and at Fort Definace are in need of the same kind of critical analysis we are given here regarding his role at Saratoga. It may turn out that Timothy Murphy isn’t such a bad guy after all.

I read your article with great interest as I have been doing research on Morgan’s Riflemen and Tim Murphy. Regarding your statement, “In 1853, a letter dated 28 November 1781, four years after the battle, written by British officer Joseph Graham (not to be confused with James Graham, a biographer of Daniel Morgan) was published in the Virginia Historical Register,” that article makes reference to the original published by The United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine published in 1834. In it, the author states that the letter comes from a journal left behind by British General SAMUEL Graham, who invited Brig. Gen. Morgan to dinner. It was on this occasion that Morgan made the quoted statement about the shooting of Brig. Gen. Fraser. I agree with Daniel Boggs that, while there isn’t a plethora of corroborative evidence, Mr. Simms’ source should not be taken lightly. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hw27wy?urlappend=%3Bseq=321 pgs. 309-313

Mr Harrington, thank you for a well-phrased review of a full-grown story on the mythology of the Battle of Saratoga rifleman.

Have you come across the account of a private Critchlow, who, in company of others was among the riflemen who succeeded in killing General Fraser? The last account I have found, in a 1909 history of Butler County, Pennsylvania, is the most graphic, but even that account does not claim Critchlow was the sole individual who fired the fatal round. Citation: James A. McKee. 20th Century History of Butler and Butler County, Pa., and Representative Citizens, pub: Richmond Arnold, 1909, Volume 1, p. 298. This account of Critchlow was denied by a historian in 1941 with the dismissive statement that no Critchlow had been found to have served under Col. Morgan. This denial is factually in error.

I have not been able to confirm William Critchlow being in Col. Daniel Morgan’s Company in the months leading up to the Battle of Saratoga.

However, I have confirmed a David Critchlow (Crutchlow) and likely his son, James, as well as a Saml Critchlow served under Captain James Knox in Col. Morgan’s regiment of “detached riflemen” during those months of 1777. The monthly payrolls are in the National Archives and digital scans are available online on the pay site Fold3.com.

Howard Appell,

….and where are you sources for all of this ???

History alone knows who made the fatal shot..when I analyze anything..I look for similarities in the accounts. Although this doesn’t prove anything..it adds credibility.

Several accounts state Morgan ordered his best shots into the trees..because of the distance and topography we can assume.

Several accounts relate the horse being grazed or wounded. Only one man on the field is known to have a switch barrel flintlock rifle..Timothy Murphy.

The good General took his fatal ball in the stomach..that is well documented.

The odds look good for old Tim !

I have lived in Middleburgh, Schoharie County, NY, for the past 21 years. Tim is revered here. Tim’s second wife Mary applied for a pension in 1860 when she was 77 years old. According to a letter in the pension file from 1928, her request was denied because she did not provide “proof of the alleged service.” (The original application document on Fold 3 is unreadable to my eyes.) Tim had died in 1818, and they were not married until 1811 when Tim was 60 and she was only 27. He was old enough to be her grandfather. I just do not think she really knew much about Tim’s service or perhaps, at her advanced age, forgot the details. I would not take that pension application as evidence that Tim was not at the Battle of Saratoga. There are payroll records for a Timothy Murphy in Morgans Rifle Corp. dated 1777, 1778, and 1779 (available for viewing on Fold3). I have been reading journals from the Sullivan Expedition in 1779 and according to one officer, Tim did have a reputation as a marksman and a great soldier. This is from the journal of Lieut. Col. Adam Hubley dated September 13, 1779: “This Murphy is a noted marksman, and a great soldier, he having killed and scalped that morning, in the town they were at, an Indian, which makes the three and thirtieth man of the enemy he has killed, as is known to his officers, this war.” It is unlikely that the Rifle Corp would have left one of their best soldiers behind as they marched to Saratoga. Regarding the shot that killed General Fraser, whether Tim told one of his sons a tall tale, or whether his son told Simms a tall tale, or whether it is a true story passed down by Tim to his descendants, cannot be ascertained. Tim was illiterate and could not write his own journal or memoir so all he really had was oral tradition. Since Morgan, in the account in the 28 November 1781 letter by Joseph Graham, did not give the name of the sharpshooter in the tree who fired the fatal shot, it seems impossible to know, but it is possible it was Tim. There are other stories about Tim that seem far more outrageous: that he shot at a messenger bearing a flag of truce, basically leading a mutiny at Middle Fort against Major Melancthon Woolsey, and according to Simms, stalked and hunted a Mohawk named Seth Henry who returned to Middleburgh after the war. I wonder if those stories also had their origins in the oral histories done by Simms