Dear Mr. History:

Dear Mr. History:

What’s the story on Nathan Hale? Like countless American schoolchildren, I was taught that he was executed for spying and said “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” A spy who gets caught seems like a dubious distinction to me. Was Hale an effective spy? And did he actually say that famous line? Sincerely, Dubiously Doubting.

Dear Dubiously:

I think that since he volunteered to be a Continental Army officer and again for a dangerous intelligence mission, Nathan Hale was a great American. However he was also a really, really poor spy. But that wasn’t entirely his fault. Here’s what happened.

At the end of August 1776, General Washington’s Continental Army held Manhattan Island after being forced to relinquish Long Island to British forces under the command of General William Howe. Washington expected a British attack on the island or elsewhere and desperately needed soldiers to spy behind British lines, observe their preparations, and report back to him about where and when it may occur.

The trouble was, few people wanted to be spies. At the time, battlefield scouting by soldiers in uniform was an accepted practice, as was espionage in diplomatic circles. But spying by soldiers or civilians who skulked around behind enemy lines incognito was considered to be low work, unfit for gentlemen. Soldiers also knew that to be caught spying was usually punishable by death. The Continental Army had no intelligence corps at that time, and neither Washington nor his staff had any experience in running spy operations. But they tried anyway, and their first attempts at sneaking a few men into British camps succeeded, but the information the soldiers gained lacked focus and detail.

Nevertheless, in early September, Washington asked Lt. Col. Thomas Knowlton, commander of a specially-formed regiment of scouts, to recruit a few spies from his ranks. One soldier responded to Knowlton’s pitch with, “I’m willing to fight the British and, if need be, die a soldier’s death in battle, but as for going among them in disguise and being taken and hung up like a dog, I’ll not do it.” It’s tough to argue against that logic.

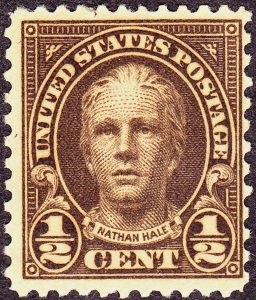

But Nathan Hale stepped forward, and he seemed the perfect Patriot. By all accounts he was intelligent and devoted to the American cause. He had blue eyes, light brown hair, and fair skin, though parts of his face were marked by an old gunpowder burn. He graduated from Yale at the age of 18 in 1773 and was teaching school in Connecticut when the Revolution began. Hale joined a Connecticut regiment in July 1775, and in September 1776 he was a captain with Knowlton’s Rangers. But, bored and frustrated at having never been in a major action, he considered Washington’s offer. Hale’s friend and fellow officer William Hull advised him not to accept the mission, but Hale replied that if his country needed him to conduct a “peculiar service,” however unsavory it was, duty and honor compelled him to comply.

Sometime before September 10, Hale visited Washington twice and received instructions to cross to Long Island from Connecticut, move west to British camps in Brooklyn, observe their preparations, and return to Connecticut. They also worked out that Hale would travel in the guise of a Loyalist schoolmaster, a role that he should have been able to act. His Yale diploma would serve as his teaching credentials.

Here, Hale’s mission began to fall apart, truly before it began. Successful spying is complicated; among other matters, agents require training, codes for note-taking and communication, and money to fund their activities. Hale probably had none of these. There was no cover story for his absence from Knowlton’s Rangers. And his cousin, Samuel Hale, was a Loyalist serving with British forces and Nathan’s powder burns made him easily recognizable. The Americans were putting Hale’s mission together with about the same level of expertise that I would bring to assembling a Lamborghini.

On Sunday, September 15 Hale arrived in Norwalk, Connecticut, to prepare to cross Long Island Sound. He exchanged his uniform for a suit of civilian clothes with a round, broad-brimmed hat, the kind that New York schoolmasters wore. He surely would have been interested to know that on that same day, British forces finally landed on Manhattan at Kips’ Bay. Washington no longer needed warning about an attack that already occurred. Nobody cancelled Hale’s crossing, though his mission was now pointless.

The night of September 16, the Continental schooner Schuyler put Hale ashore near Huntington on Long Island. Exactly what happened to him after this is not entirely clear, though we know that he was captured on September 21. One version of his activities is that Hale made it to New York City, where his Loyalist cousin Samuel spotted him and revealed his true identity. Another is that Redcoat pickets captured Hale trying to return to Huntington. However in 2000, the Library of Congress obtained an unpublished manuscript account written during the Revolution by a Loyalist shopkeeper in Connecticut named Consider Tiffany. Some historians consider it to be the most credible. According to the Tiffany account, it was Robert Rogers, the famed American officer of the French and Indian War but now a Loyalist, who captured Hale.

The barely-prepared Hale could not have had a worse enemy than Rogers, who was a grizzled veteran of countless frontier battles and political schemes, and described as “subtil & deep as hell itself.” Commissioned as the commander of the Loyalist Queen’s American Rangers, Rogers was bent of ferreting out Rebels and had informants throughout Long Island and Connecticut. Based on their information, Rogers suspected that an American spy drop occurred near Huntington. He guessed the spy’s destination as Brooklyn, and on September 18 he landed with a party of his Rangers at Sands Point, mid-way to Brooklyn, to intercept the Rebel.

Within a day Rogers spotted Hale, who was traveling on a coastal road and somewhat conspicuously asking questions and taking notes. On Friday September 20 Rogers dressed as a civilian and opened a conversation with Hale at a tavern, baiting the younger man by posing as a Rebel supporter and toasting to Congress. Hale thought he was among friends and admitted that he was on a mission for Gen. Washington. A cardinal rule of spying is to never talk about spying. It’s like Fight Club. We could use many terms to describe Hale’s admission – “foolish” is one of the tamest. But let’s not judge too harshly – the adage “old age and treachery will overcome youth and skill” applies here, and Hale was plenty youthful and short on skill. Rogers arranged for another meeting the next day to introduce Hale to other Rebels, so he said. At the next meeting Rogers brought three or four Rangers, also dressed as civilians, who he introduced as friends. Hale admitted his mission once more, and the Rangers seized the hapless spy.

Rogers took Hale to the British headquarters in New York City that night. There was irrefutable evidence that Hale was a spy – he had twice admitted his mission, was in disguise, and had notes on British activities. The timing also could not have been worse because that same day a fire – which the British believed was set by American spies – swept through much of New York City, and the Redcoats had already hanged some suspected saboteurs. Howe signed Hale’s death warrant on the spot.

The next morning, Sunday, September 22, Redcoats marched Hale to their encampment next to the Dove Tavern, today Third Avenue and Sixty-Sixth Street. Nearby was a tree with a ladder against it and a freshly-dug grave. A noose hung from one of the tree’s branches about 15 feet above the ground. With his hands bound behind him, Hale shakily climbed to the top of the ladder and his captors allowed the traditional final words.

Think for a moment about the tragic thoughts that ran through Hale’s mind as he saw his early, ignoble death as a spy slowly approaching. He may have replayed the events of his capture over and over in his head, wishing he had made different choices. As a devoted Congregationalist, he may have felt comfort at going to meet his maker on a Sunday. But he probably knew that whereas a proper noose snapped a man’s vertebrae for an instant death when tied correctly and placed under the victim’s chin – an improper noose merely tightened around the neck, and slowly strangled a person to death.

There is no trustworthy record of Hale’s exact last words. The accounts with his “I only regret . . ..” line were published much later, and some historians question their validity. If Hale actually said those words, he was probably paraphrasing “What pity is it that we can die but once to serve our country,” from Cato, by Joseph Addison; one of his favorite plays.

Possibly the most reliable account of Hale’s death comes from Lt. Frederick MacKenzie, a British officer who witnessed the execution and noted in his diary that Hale “behaved with great composure and resolution, saying he thought it the duty of every good officer, to obey any orders given him by his Commander-in-Chief; and desired the Spectators to be at all times prepared to meet death in whatever shape it might appear.” That alone ought to cinch Hale an honorable place in the history books.

With Hale’s last words, soldiers kicked the ladder away. The hangman was a recently escaped slave, inexpert in the trade, and Hale probably suffered an agonizing death. His body was left swinging for a few days as an example, and some soldiers hung a board on the corpse with “General Washington” written on it.

The Americans learned of Hale’s death the evening of the 22nd when Gen. Howe’s aide-de-camp Capt. John Montressor met with a party of Continental officers under a flag of truce to discuss a prisoner exchange. As an aside, Montressor informed the party that a Capt. Nathan Hale had been executed for spying. Washington’s aide, Capt. Tench Tilghman, wrote soon afterward, “General Howe hanged a Captain of ours belonging to Knowlton’s Rangers who went into New York to make discoveries. I don’t see why we should not make retaliation.” But Washington had his hands full battling the British for control of the rest of New York, and he neither mentioned Hale’s death publically nor launched any retaliation. The Hale incident faded into the background as the war moved on. Only two newspaper articles describing his fate appeared during the Revolution.

In the early nineteenth century Hale became known as an officer who exemplified the character of a Patriot, and his story gained popularity. Hale’s famous quote probably comes from the memoirs of his friend William Hull, who claimed to have heard about the execution from the British aide-de-camp, Capt. Montressor. But some historians question Hull’s story for multiple reasons; prime among them that it was recorded third-hand by his daughter and not published until 1848, 23 years after Hull’s death.

If there is any positive side from this – and that’s a tough silver lining to find – it is that Washington learned much from the Hale fiasco. With the assistance of able officers like Major Benjamin Tallmadge, who was Hale’s close friend, Washington established an efficient spy network in New York City with properly managed agents who communicated through messages written in code or with disappearing ink. The new American spies served to the end of the Revolution, and today Washington is rightly regarded as a master of the intelligence business. But that, as they say, is another story.

There is much more story to the Hale misadventure, as well as other versions of his capture. To read more, check out the excellent, Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring, by Alexander Rose, Nathan Hale: The Life and Death of America’s First Spy, by M. William Phelps or the Library of Congress Information Bulletin, Nathan Hale Revisited: A Tory’s Account of the Arrest of the First American Spy, by James Hutson.

And if you’re skulking around incognito, never, ever admit what you’re doing. Like, never.

Recent Articles

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...