In all times and places, people have engaged in trade, and the American Colonies during the time of the Revolution are no exception. Although some trade was conducted as barter, particularly for commodities such as tobacco or beaver pelts, it was common for people to use coins (of nearly any country – Spanish dollars were in wide circulation) or paper money.

In the years prior to the Revolution, responding to shortages in available coin and paper money, the colonies had each established their own currencies, based on the British system of pounds, shillings and pence. Keeping track of how the value of the different colonies’ pounds related to British pound – and to one another – vexed many who traded and traveled among the colonies, and hindered trade between the colonies.

Inflation resulting from over-issuance of these bills, and the wide variation in the value of the different colonies’ pounds finally led Parliament to pass a number of Currency Acts to restrict the issuance of paper money in America[i]. These acts are among the factors that raised tensions between the Colonies and the mother country, and it’s likely that they contributed to the break with the Crown, as they caused even greater hardship for Colonial trade.

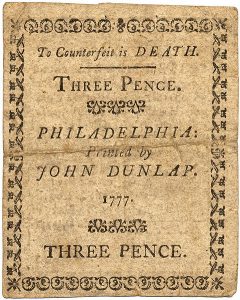

Once the rebellion began, all of the rebel colonies began issuing paper currency with abandon, in order to pay soldiers, purchase supplies and war materiel. In addition, the Continental Congress authorized the issue of a national currency, known as “Continentals.” In a conscious attempt to break from the British denominations, these bills were issued in dollars and fractions of dollars. The word “dollar” was a well-known term for Spanish pieces of eight, and derived the German thaler, which referred to a large silver coin.[ii]

All of these currencies were subject to rampant inflation, as the issuing bodies simply printed more as needed to cover expenses, and the phrase “not worth a continental” came to be widely used. Worse yet, the British government in New York undermined the fledgling currency through massive counterfeiting operations.[iii] By the end of the war, these bills were so worthless that they could only be redeemed for Treasury bonds — at just 1% of their face value.[iv]

As a result of these impediments, many merchants in the Revolutionary Era avoided using cash at all, with the exception of hard money – foreign coins, often those from Spain, or Portugal – instead keeping complex credit account books, which were often paid off in goods or services. This “bookkeeping barter” allowed merchants to track their customers’ purchases in a currency familiar to both, and customers to fulfill their debts by delivering anything from agricultural goods, to crafts, to labor, as suited both parties.[v]

Although the US dollar was officially established as the national currency after the end of the war, along with the innovative decimal division into dimes and pennies, the old ways died hard. In the 1820s, John Quincy Adams reported that the dime was “utterly unknown,” whereas a Spanish reale would be accepted as a shilling in New York, nine pence in Boston and eleven pennies in Philadelphia, all based on the “absurd” application of English denominations to Spanish coins.[vi]

By the time of the Civil War, though, nearly a century after the American Revolution, our modern ideas of the American dollar had prevailed. Aside from the departure from the gold standard in the early part of the 20th century (and the attendant inflation since that time), our monetary system has been largely unchanged since that time, with the familiar pennies, nickels, dimes and quarters, and various denominations of paper currency for the dollar and beyond.

[i] Allen, Larry. The Encyclopedia of Money. 2nd edition. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2009, p. 96-98.

[iii] Kenneth Scot, Counterfeiting in Colonial America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000, 259–60.

8 Comments

I have been puzzled about the currency ever since I first heard the term “not worth a Continental.” This article really helped fill in major gaps in my knowledge. Thanks!

Ezra Tilden, a Revolutionary War vet from Stoughton, Mass., who kept a journal (mini-published by the Stoughton Historical Society) during his Ticonderoga service in the summer of 1776, grumbled that an edict had gone out that ONLY Continental money could be used for any transaction at the Ti. However, he rightly assumed that silver would always be good…and it is. Ezra was always, buying, selling, or swapping something. He describes no battles, first hand, but his descriptions of camp-life and soldierly commerce are exceptionally detailed.

Thanks, Hugh – glad to hear that this was informative!

Dwight, I wish I’d had that journal when I was writing The Prize – those are the sort of details that are just wonderful to include, to give readers a sense of the time.

Do you have a link where the Society’s republication of it can be acquired?

We don’t have our publications listed on our website yet, but if you send $20 to Stoughton Historical Society, Box 542, Stoughton, MA. 02072 and we will mail you one.

The Revolutionary War Diaries of Stoughton’s Ezra Tilden Tilden served in eight campaigns; this journal covers two of them in the summer/fall of 1776 and 1777, respectively, including the Battle of Saratoga, which many consider the turning point of the Revolutionary War. His entries describe long marches, his critical illness at Ft Ticonderoga in 1776, the terrible aftermath of a major battle, his faith in God, several dreams, a song of celebration, his comrades from Stoughton, and many examples of his entrepreneurial, Yankee character.. $15 Members $10, By mail: $20

Here is a blurb from Eric Schnitzer at Saratoga: “…this account is truly extraordinary”

I have to tell you, that of all the journals I have read from participants here at Saratoga, no matter what side they were on, his is one of the most compelling. It is, in fact, the most detailed account of a militia soldier’s day-to-day activity from the campaign, and is one of the most so of all accounts from the entire war. His record of daily detail are something almost always passed over by other journalists…this account is truly extraordinary. It proves once again that there are more gems out there which are otherwise unknown or little known, and thanks to the efforts of the Stoughton Historical Society, Tilden’s story can now be told; we have learned a lot from it, and in turn, we can teach the many tens of thousands of visitors we come into contact every year about Tilden’s experience….Thanks again; I cannot tell you how exciting this new account is! Thank you for sharing it with us.

Yours Sincerely, Eric H. Schnitzer Park Ranger/Historian, Saratoga National Historical Park (November, 2009)

By the way, this journal led me to “discover” the Crown Point Road, which Amherst had built after Crown Point fell to the Brits. Obviously other people knew about it, but it is not until I re-traced Tilden’s march by car, that I learned of it.

Dwight

An excellent and interesting piece! I had no idea how our dollars came to be, and to me it rather underpins the point that currency of all sorts is absolutely arbitrary. I once heard someone make the comment that money is not an object, it’s a concept. I finally understand that.

Well done, Lars ! I learned something today.

Thank you !