Myth:

Americans did not formally resolve for independence until 1776.

Busted:

On October 4, 1774, the town meeting of Worcester, Massachusetts, declared that British rule was over and it was time to form a new government, not answerable to the Crown and Parliament. This act by a public body was twenty-one months before Congress approved its own Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

In the late spring of 1774, Parliament yanked away the Massachusetts Charter of 1691, which had granted people considerable say in their government. In response, on September 6 in the town of Worcester, thousands of militiamen closed the county courts, ending British rule. This left people in a “state of nature,” as people said at the time, beyond the protection of any government. Who would fill the vacuum?

On the local level, the Worcester County Committees of Correspondence assumed temporary authority. Acting in concert, the committees reorganized the militia to prepare for a counter-offensive they knew British officials would soon stage. They also promised “to put the laws in execution respecting pedlars and chapmen” and maintain civil authority in all other respects.

On the provincial level, the power void would be filled by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, slated to meet in early October. (Back in August, Worcester patriots had instigated a four-county convention of the committees of correspondence, and that convention had issued the call for such a congress.) On October 4, the Worcester Town Meeting issued instructions to the blacksmith Timothy Bigelow, its representative to that upcoming Congress. If the Massachusetts Charter of 1691 was not fully restored by the time the Congress convened the following day, which was obviously impossible, it told Bigelow:

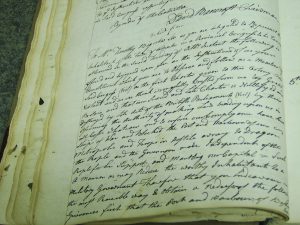

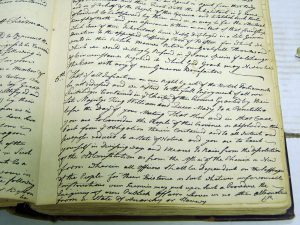

… you are to consider the people of this province absolved, on their part, from the obligation therein contained [the 1691 Massachusetts charter], and to all intents and purposes reduced to a state of nature; and you are to exert yourself in devising ways and means to raise from the dissolution of the old constitution, as from the ashes of the Phenix, a new form, wherein all officers shall be dependent on the suffrages of the people, whatever unfavorable constructions our enemies may put upon such procedure. [See image 1 above, which announces the instructions, and image 2 below, the fifth instruction, which commands Bigelow to push for a new government.]

This was indeed a declaration for independence. Since the new government must be based exclusively on the “suffrages of the people,” there could be no more monarchical prerogatives, as there were under British rule. Further, the new government would be formed without asking for the consent of existing British authorities. Although the Worcester document does not use the word “independent,” people at that point in time did label this move “independency.”

John Adams, in Philadelphia attending the First Continental Congress, wrote to a friend back home: “Absolute Independency … Startle[s] People here.” Most delegates attending the Philadelphia gathering, he warned, were horrified by “The Proposal of Setting up a new Form of Government of our own.” Samuel Adams, also at the Continental Congress, likewise cautioned the people of Massachusetts not to “set up another form of government” for fear of jeopardizing support from other colonies. Those revered revolutionaries from Boston, who allegedly drove the agenda, were trying at this moment to slow down the Revolution that had swept across the countryside. “Independency” should not come too soon, they said, and in fact it had to wait; leadership at the Provincial Congress fell into the hands of the more educated, experienced, and cautious representatives from eastern counties. If the radicals in Worcester had had their way, however, Massachusetts would have declared independence on its own, without waiting for other colonies to join in.

RESEARCH ALERT: While Worcester’s declaration for independence is dramatic and certainly worthy of note, Worcester might not have been alone. Thus far, it constitutes the earliest act by a public body pushing for independence, but other towns might have done likewise, for the Revolution of 1774 encompassed all of mainland, contiguous Massachusetts. If some aspiring researcher poured through the records of the 209 towns and districts sending delegates to the Provincial Congress, he/she might well uncover others.

Further readings:

For context on the Worcester instructions, see Ray Raphael, The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (The New Press, 2002), 29-30, 157-60. For attempts by John Adams and Samuel Adams to slow down this grassroots move toward “independency,” see Ray Raphael, “Blacksmith Timothy Bigelow and the Massachusetts Revolution of 1774,” in Alfred F. Young, Gary B. Nash, and Ray Raphael, eds., Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation (Knopf, 2011), 50-51. For town meetings issuing instructions, see J. R. Pole, Political Representation in England and the Origins of the American Republic (St. Martin’s Press, 1966): 72-75, 80, 94-95, 161-165, 211-214, 229-240, 441, 541-542; Kenneth Colegrove, “New England Town Mandates,” Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications 21 (1919): 411-449, accessible online through Google Books at http://is.gd/ivsat; Ray Raphael, “Instructions: The People’s Voice in Revolutionary America,” in Common-Place 9:1 (October, 2008), http://www.common-place.org/vol-09/no-01/raphael/. A transcription of the complete instructions (pictured) appears in Albert A. Lovell, Worcester in the War of Revolution, pages 48-50, accessed through Open Library.

Ray Raphael at TEDx:

Video link: Revolution: A Success Story: Ray Raphael at TEDxEureka, Dec. 2, 2012

4 Comments

How do our Suffolk Resolves stack up? They were finalized and taken by Paul Revere to Philadelphia a month before the Worcester document.

http://ahp.gatech.edu/suffolk_resolves_1774.html

The Suffolk Resolves (September 9), although radical, did not call for a new and independent government. This famous document, in fact, was only one of several coming from the county conventions of the Committees of Correspondence. For example, on September 6 the Worcester County Convention passed resolves similar to those of Suffolk, as did the other mainland, contiguous counties of Massachusetts from late August to early October, 1774. The only difference: Suffolk, which included Boston, was the only county NOT to overthrow British rule at that time, due to the presence of British soldiers. All the county resolves are reprinted in William Lincoln, ed., The Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775, and of the Committee of Safety, with an Appendix, containing the Proceedings of the County Conventions (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1838), 601-660.