For Maj. Arent Schuyler De Peyster, his assignment as commandant of British forces at Detroit was growing increasingly frustrating. For years, British officers at Detroit had encouraged Indian allies to strike the American backcountry, rendering the frontier a scorched arc stretching from Pennsylvania to Kentucky. But by the late summer of 1782, De Peyster was struggling with new orders. With peace in the offing, commanders at frontier posts had been directed to discourage the Indians from making further offensive attacks against the Americans while peace negotiations were underway in Paris.

In a September 29 missive, De Peyster explained his predicament to Gen. Frederick Haldimand, commander of British forces in Canada. In compliance with orders, De Peyster had requested that the tribes refrain from taking offensive action, but the change in policy was clearly vexing the Indians. It was inevitable, De Peyster observed, that American settlers would continue to make war on the Indians, and that native war parties would continue to enter American territory for prisoners and scalps. “A defensive war,” he noted, “will, in spite of human prudence, almost always terminate in an offensive one.” As the Revolution slowly morphed from a shooting war to a tenuous peace, De Peyster summed up his dilemma: “I have a very difficult card to play”, he wrote.[1]

For British officers who managed the war on the northern frontier, the diplomatic balancing act would only grow more difficult. By October 1782 Haldimand was likewise growing increasingly uncomfortable with the management of Indian relations and gingerly tried to inform his superiors in London that a complete diplomatic disaster was in the realm of possibility. According to orders he had received from Lord Shelburne, Haldimand had already begun reining in tribal war parties, ordering local commanders “in the Strongest Terms to discourage Hostile Measures on the part of the Indians.”[2]

But the tribes had suffered immeasurably in the war, and American forces continued to harass native villages. British hesitancy to supply and encourage Indian war parties was beginning to be viewed as a sign of weakness. As Haldimand put it, reduced British material support was construed by the Indians as “a want of abilities to carry on the War.” The tribes had been faithful allies but were growing disillusioned with a waning prosecution of the war. The entire affair, he wrote, had occasioned a “general discontent” among the Indians.[3]

Haldimand was a no-nonsense career officer, and tried to clarify the situation to officials in London who were micromanaging diplomacy on the frontier. Because “the Disposition of the Indians and the indispensable necessity of preserving their affections may not be Sufficiently understood at Home,” Haldimand stated his case bluntly. The good graces of the Indians, he claimed, were absolutely imperative to the British possession of Detroit. If the Indians so much as remained neutral, British troops alone could not hope to hold Detroit if the Americans launched a concerted effort.[4]

The tribes had repeatedly been assured of British victory, but were increasingly uneasy by the widespread realization that the Americans might, after all, defeat the king. The Indians, Haldimand wrote, “are Thunder Struck at the appearance of an accommodation So far short of their Expectation from the Language that has been held out to them, & Dread the idea of being forsaken by us.”[5]

Such apprehensions were becoming unavoidable as subtle changes in British management of the war became increasingly obvious. In a cost saving move that anticipated an inevitable peace, the British Indian Department was ordered to reduce its staff. During January 1783, several interpreters were dismissed, a handful of others had their pay reduced from $2 per month to $1 per month, and any of the lower-ranked “four shilling men” were to be dismissed unless their services were considered indispensable.[6]

At a council convened in April 1783, De Peyster was confronted by tribal delegates at Detroit who were anxious to continue the war and suspicious over the terms of an impending peace. For his part, De Peyster continued to stall for time. The king, De Peyster claimed, had very good reasons to restrain Indian war parties the previous autumn, and “he has the same reasons yet. Your Great Father is willing to give peace to his enemies, and they are about settling matters.” Because peace negotiations were underway, De Peyster explained that it was Haldimand’s wish that the Indians “remain quiet until he can hear from the King.”[7]

A skeptical Wyandot chief gave voice to tribal concerns over the disposition of Indian rights in any potential treaty. The chief implored that “Should a Treaty of Peace be going on we hope your children will be remembered.”[8] As events would prove, such hopes were misplaced.

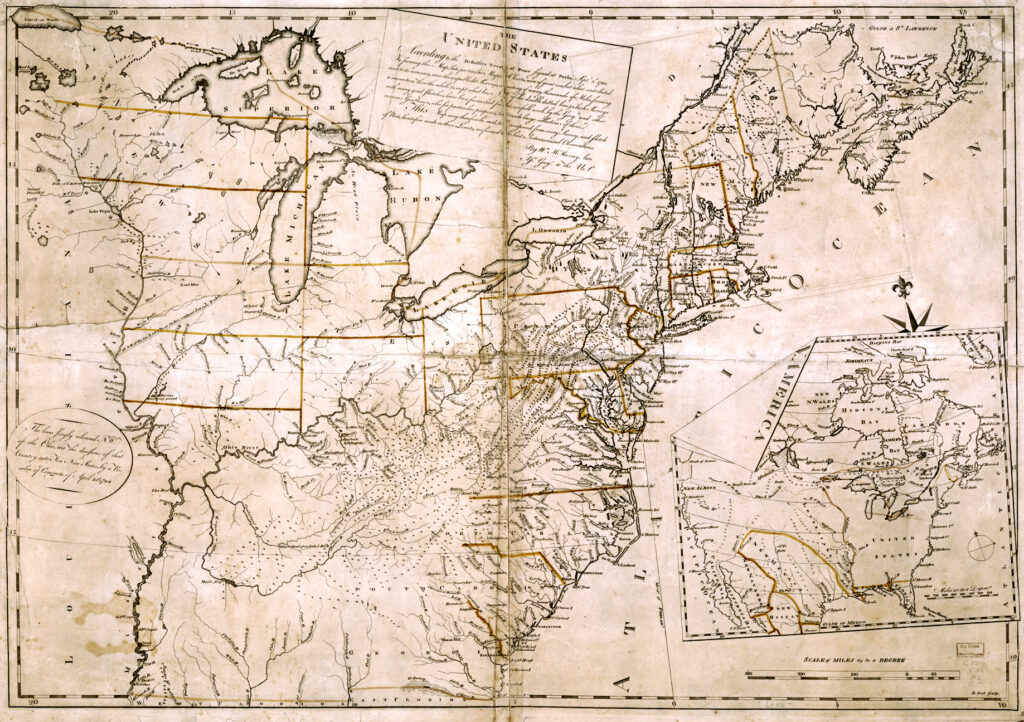

Ironically, just days after De Peyster was stalling for time in Detroit, Haldimand unsealed a staggering communique from London. Haldimand was aghast as he read official notification of a cessation of hostilities, as well as a copy of the preliminary peace treaty. The king had “ceded” to the Americans the bulk of the western country, a vast territory bound to the north by the Great Lakes, to the west by the Mississippi River, and to the south by the border with West Florida.

Ostensibly included in the deal were all of the major western posts, including Niagara, Detroit, and Michilimackinac. The installations were not only of value militarily, they were centers of the fur trade and vital to native economies. In what would come to be regarded as an egregious insult, His Majesty’s Indian allies were not so much as mentioned in the treaty. Immediately recognizing that the treaty’s boundary provisions would understandably enrage the natives, Haldimand decided to stall for time and delay the public release of the treaty.

An exasperated Haldimand, mortified at what he considered a stain on national honor, poured out his frustrations in a letter to Gen. Friedrich Riedesel. The Indians had served as faithful allies of the Crown and had suffered tremendously by siding with Britain. Now that the fighting was coming to a close, it seemed that the tribes were being abandoned. “My soul is completely bowed down with grief,” Haldimand wrote, “at seeing we (with no absolute necessity), have humbled ourselves so much as to accept such humiliating boundaries. I am heartily ashamed, and wish I was in the interior of Tartary.”[9]

British officials across the northern frontier found themselves in the same disagreeable position. After regularly supplying native war parties out of Niagara, Brig. Gen. Allan Maclean was forced to perform an abrupt about-face. Under orders from Haldimand, Maclean had directed his own men to stand down from participating in Indian raids, and did everything in his power to restrain his tribal allies from carrying out their own attacks. In a May 2, 1783 letter to George Washington, Maclean deflected blame for killings that had taken place contrary to current British policy. Maclean explained that he had ordered a halt to offensive operations and that he had largely succeeded in defusing further bloodshed. “At the same time,” wrote Maclean, “I must do the Indians the justice to declare, that, notwithstanding the very great provocation they met with, They have implicitly followed the directions given them by me.”[10]

On May 6, 1783, the sloop Felicity arrived at Detroit with official notification of the treaty, and De Peyster immediately recognized, as he put it, the “necessity of restraining the Indians more than ever.” He immediately dispatched letters indicating as much to various tribes, and he also informed Indian Department officers who were working in villages scattered across the Ohio country.[11]

Despite Haldimand’s and DePeyster’s attempts to conceal the details of the treaty from the Indians for as long as possible, whispers regarding a potential cession of Indian land began to leak out. Later in May 1783 tribal leaders directly confronted De Peyster at Detroit. The flummoxed officer explained that he was entirely sympathetic to their plight but was bound by events, and decisions, largely out of his control.

Due to the “surmises” that had circulated regarding potential boundaries, De Peyster reported that the Indians “look upon our conduct as treacherous and cruel.” The natives were simply aghast that the king could even consider ceding territory to the Americans that never belonged to him in the first place. The land in question was Indian land, and had been recognized as such by all parties since the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. The king, the Indians pointed out, “had no right whatever to grant away to the States of America their rights of properties without a manifest breach of all justice and equity”, adding defiantly, “they would not submit to it.”[12]

Slowly, news of a proposed peace trickled west. Along Michigan’s Huron River, Moravian missionary John Heckewelder recorded that the first rumors of peace preliminaries reached his people during May and June, but that “it was believed by few of the Citizens that it would be the Case.” The news was largely discounted until two men arrived from Pennsylvania to corroborate the stories.[13]

Haldimand had his own uncomfortable meeting with one of the king’s most faithful allies on May 21. In a rather tense confrontation, the famed Mohawk leader Joseph Brant demanded to know the facts regarding the treaty. Brant reminded Haldimand that the Mohawks had graciously befriended the English when “we were a great People . . . and you in manner but a handful.”[14]

Details regarding the boundary provisions of the treaty seemed like a monstrous betrayal. The tribes were clearly growing tired with prevarication, and wanted the whole truth. Tellingly, Brant addressed Haldimand not with the traditional tribal honorific of “father,” but simply as “brother.” Brant wanted a decisive answer whether the Indians “are included in this Treaty with the Americans as faithful Allies should be, or not?” and whether Indian land “is secured to them.”[15]

In what Haldimand surely took for a stinging rebuke, Brant asked if more Indian blood would be shed to defend their land “thro’ the means of our Allies for whom We have so freely bled.”[16] Not surprisingly, the governor could muster little more than a tepid response. Still attempting to hide the details of the treaty, Haldimand brushed Brant off as best he could, assuring the Mohawk that he was held in high esteem, and repeating his standard answer that further details regarding the treaty would be forthcoming from the King.

On June 28, a Ouiatenon chief from the Wabash River delivered up an American prisoner to De Peyster at Detroit. Fresh from a raid against the Americans, the chief was outraged by what he considered British duplicity, and scolded De Peyster. “We are informed,” the chief said, “that instead of prosecuting the War, we are to give up our lands to the Enemy, which gives us great uneasyness – in endeavoring to assist you it seems we have wrought our own ruin.”[17]

De Peyster was forced to respond with noncommittal vagaries, and explained that he had still not officially received the particulars of the treaty from his own superiors. The best De Peyster could do was offer transparently patronizing compliments. “I tell you the World is now at Peace,” he assured the chief, “and you have saved your Lands, but had you not defended them agreeable to my desire, the Americans would have taken them from you.”[18]

Despite British stonewalling, the ugly reality of the treaty provisions was beginning to reach the remotest corners of the Great Lakes. At Michilimackinac, an angry Ottawa chief, who clearly understood that the British were being less than forthright over the treaty, scolded Capt. Daniel Robertson. The negotiations had clearly not gone well, or, as the chief colorfully put it, “he was afraid the Tree was fallen on the wrong side.” The facts should have been plainly put to the Indians, but obviously hadn’t been. Disgustedly dismissing the entire affair, the Ottawa chief bluntly announced that “I believe all of you have been telling us lies.”[19]

By the end of June 1783, De Peyster found it increasingly difficult to keep a lid on the facts. In a letter to Allan Maclean, De Peyster explained that the Indians, clearly suspicious of British intentions, were constantly hounding him for more information. A basic outline of the treaty wasn’t a secret anymore; a number of the Indians, as well as white captives and American renegades, were fully capable of reading newspapers. But when it came to the specific treaty articles relating to the cession of Indian lands, De Peyster had thus far been able to keep them secret.

Both officers were clearly scrambling for a way to announce the boundary articles to the Indians without precipitating further unrest. Maclean stated the obvious; there was simply no way to keep the cession of lands a secret indefinitely. Maclean had started sending out officers from Fort Niagara, informing the Indians that as soon as he received an official copy of the treaty, the tribes would be called together for a general council.

In the meantime, Maclean advised the Indians to “pay no attention to any stories from bad birds.” He was outraged that the Americans had already sent emissaries into the heart of the Iroquois country under the very noses of the British at Niagara. The Americans were sure to make propaganda hay out of the terms of the Treaty of Paris, and the fiery Scotsman became virtually apoplectic as he railed against the “designing hipocritical neighbors the Americans. . . . There is no bounds to the Effrontery & Impudence of these new upstarts.”[20]

The Americans certainly viewed the bad blood that had developed between Britain and her Indian allies as a priceless diplomatic opportunity. Hoping to arrange an exchange of prisoners, Maj. George Walls arranged a council at the Falls of the Ohio River that summer. Walls attempted to alienate the Indians from their erstwhile allies, informing them that that the English “have made peace with us for themselves, but forgot you their children who Fought with them, and neglected you like Bastards.”[21]

A more formal effort to alienate the Indians from Great Britain would materialize that summer. Ephraim Douglass, a former officer and Indian trader, headed up a peace commission to the northwestern tribes early that summer. Highly respected in western Pennsylvania and fluent in several Indian languages, Douglass was considered the ideal man for the job.

Douglass arrived at the Sandusky villages of western Ohio during the middle of June, where he met with the influential Delaware chief Pipe. Douglass was shocked to find that the tribes were being kept in the dark regarding the boundary provisions of the Treaty of Paris. Douglass proceeded to inform Pipe regarding “the Preliminary Articles of Peace, which I found had not only never been communicated to them by authority, but that the accidental information they had occasionally received had been in some respects contradicted by the Officers of the Crown; particularly that part which related to the evacuation of the posts on the Lakes.”[22]

Douglass reached Detroit on July 4, where he met with De Peyster. The two men held a cordial meeting, and Douglass requested permission to meet personally with the local Indians. The Detroit commandant told Douglass that he would “willingly promote all in his power” to effect a peace between the “United States and the several Indian Nations.” But regarding any potential council with the Indians, De Peyster shrewdly demurred.[23]

Although De Peyster had already been informed of the new boundaries, he assured Douglass that until he received official authorization from his superiors, “he could not consent that any thing should be said to the Indians relative to the boundary of the Unites States; for though he knew from the King’s Proclamation that the war with America was at an end, he had no official information to justify supposing the States extended to this place, and therefore could not consent to the Indians being told so.”[24]

In fact, De Peyster was in an uncomfortable position. He had “uniformly declared” to the Indians that he was unaware that the western posts were to be evacuated by the British, but obviously knew that the treaty provisions certainly called for the Americans to eventually occupy the forts. Douglass went so far as to suggest a council with the Indians that would leave the boundary question unaddressed, but De Peyster brushed the idea aside. De Peyster seems to have charmed Douglass with what the American commissioner described as “very civil” treatment, but ended up simply shunting the American commissioner off toward Niagara.[25]

Douglass arrived at Niagara on July 10, where post commandant Allan Maclean thought Douglas a “shrewd sensible man” who behaved with complete propriety. Maclean nonetheless endeavored to keep Douglass – and any information regarding future boundaries—away from the Indians. Despite Maclean’s efforts, Joseph Brant, who clearly didn’t regard himself or his people as being subservient to the British, arranged a personal meeting with Douglass.

During their informal meeting, the two men, claimed Douglass, “had a good deal of friendly argument.” Brant was clearly focused on future boundaries, and vowed that there would be no peace until Iroquois land rights were secured. Despite the contention, Douglass left the conversation convinced that the Indians were “heartily tired of the war and sincerely disposed to peace.”[26] At least according to Maclean, however, Douglass seems to have regarded the trip as something of a failure. The Scotsman reported that Douglass “candidly confessed, that part of his instructions had much better been omitted.”[27]

From the British perspective, something clearly had to be done to forestall worsening relations with the Indians. Beginning on September 5, 1783, representatives from over a dozen Indian nations met at Lower Sandusky in northwestern Ohio to hammer out their grievances with the King. Heading up the British delegation was Alexander McKee, the deputy superintendent of the Indian Department who was highly respected by the tribes. Also present was Joseph Brant, as always wielding his considerable intellect as a loyal Crown surrogate.

McKee made it clear that peace had been achieved with the Americans, and spun the facts as best he could under the circumstances. McKee presented a morale-boosting message from Sir John Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, but then moved on to the tricky question of boundaries. Knowing that the specifics of the treaty’s boundary provisions were widely known, McKee explained the matter as best he could. “You are not to believe,” he announced, “that by the line that has been described, it was meant to deprive you of an extent of country, of which the right of soil belongs to you. . . . Neither can I harbor an idea that the United States will act so unjustly or impolitically as to endeavor to deprive you of any part of your country under the pretext of having conquered it.”[28]

Brant likewise passed along Johnson’s assurances that “the boundary Line lately agreed to, did not deprive us of our lands.” He also hinted at continued British material support in case war erupted again. Although it was the king’s wish for the tomahawk to be “laid down,” if the Americans “give us just cause to use it, we shall nevertheless be able to take it up in defence of our Rights.”[29]

For McKee, the council was a success; as he put it, the meeting had “been of singular service in removing the doubts and uneasiness which those nations were under on our parts.”[30] Tribal delegates were pleased with his promises of continued support, and appeared satisfied with his explanations regarding the territorial provisions of the Treaty of Paris. From the Indian perspective, the Americans had been granted the opportunity to purchase Indian land—a right formerly enjoyed by both the French and the British—but had secured no absolute territorial rights.

Britain’s treatment of the Indians would occasion humiliation on both sides of the Atlantic. In defending the terms of the treaty in regard to the Crown’s Indian allies, Prime Minister Lord Shelburne rejected accusations that Britain had dishonorably abandoned her friends and offered an overly sanguine characterization of the situation. “The Indian nations were not abandoned to their enemies,” he asserted, “they were remitted to the care of neighbors, whose interest it was as much as ours to cultivate friendship with them, and who were certainly the best qualified for softening and humanizing their hearts.”[31]

American authorities entertained different notions. Just one month following the Sandusky council, an American Congressional committee issued a report that would lay the groundwork for another generation of tragedy on the northwestern frontier.[32] After recounting the ugly reality of Indian atrocities, the committee nonetheless thought it best to show restraint. “Waiving then the right of conquest,” read their report, “a bare recollection of the facts is sufficient to manifest the obligation they are under to make atonement for the enormities which they have perpetrated.”[33]

Congress observed that an Indian war was simply too expensive to prosecute at that time, and it was far better to compensate the Indians for future cessions rather than secure them by force of arms. Future treaty commissioners were to remind the Indians of their past aggressions, as well as the fact that the king had ceded North America as far west as the Mississippi River. The Indians needed to be pushed for more land, but only so far. “Care should be taken,” Congress admonished, “neither to yield nor require too much.”[34] As subsequent events would unfortunately prove, threading that diplomatic needle would prove impossible.

During October 1784, American treaty commissioners Oliver Wolcott, Richard Butler, and Arthur Lee met with Iroquois delegates at Fort Stanwix, New York. The subsequent negotiations would result in the first major treaty between the nascent United States and the northern Indian nations, and would set an unfortunate diplomatic precedent. The blatant exclusion of the Indians from the text of the Treaty of Paris loomed large during the negotiations.

Speaking for the Iroquois, the Mohawk war leader Aaron Hill voiced his people’s position. “We are free and independent,” Hill asserted, “and at present under no influence.” Although the Iroquois had previously been allied to the king of Britain, “he having broke the chain [of friendship] and left us to ourselves, we are again free and independent.”[35]

The trio of commissioners adopted a decidedly aggressive bargaining posture, and completely dismissed Iroquois attempts to negotiate on an equal footing. “You are mistaken,” replied the commissioners, “that having been excluded from the United States and the King of Great Britain, you are become a free and independent nation, and may make what terms you please. It is not so, you are a subdued people.” The commissioners further explained that the king had ceded the whole of the disputed territory to the United States, which “by right of conquest” could lay claim to the land in any event.[36]

The commissioners then got to the crux of the matter: the American need for more land. The growing population of the United States necessitated the acquisition of more land “essential to their subsistence. It is therefore necessary that such a boundary line should be settled, as will make effectual provisions for these demands, and prevent any future cause of difference and dispute.”[37]

As the Seneca chief Cornplanter spoke for his people, he countered that the Indians, though comparatively small in population, needed a “large country to range in, as indeed our subsistence must depend on our having much hunting ground.” The Treaty of Paris, ostensibly penned to bring an end to bloodshed, ultimately aggravated a festering wound between two divergent cultures that were at loggerheads over their views regarding the use of the land. With the tragic hindsight of two centuries, it’s evident that a peaceful accommodation between the United States and its Native American neighbors was simply not attainable. Despite the seemingly irresistible power of the United States, territorial conflict was inevitable. As Cornplanter explained it, “we Indians love our lands.”[38]

[1] J. Watts De Peyster, ed., Miscellanies by an Officer (New York: A.E. Chasmer & Company, 1888), xi.

[2] Henry S. Batholomew, ed., Michigan Historical Collections (Lansing: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., 1908), 10:662-663.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] de Peyster, Miscellanies, 2:xxxix.

[7] Ibid., 2:xii-xiii.

[8] Michigan Historical Collections, 11:355.

[9] Isabel Thompson Kelsay, Joseph Brant: Man of Two Worlds (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1984), 339.

[10] Allen Maclean to George Washington, May 2, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washinton/99-01-02-11208.

[11] De Peyster, Miscellanies by an Officer, 2:xi.

[12] Michigan Historical Collections, 20:118-119.

[13] Paul A. Wallace, ed., The Travels of John Heckewelder in Frontier America (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1958), 204.

[14] Kelsay, Joseph Brant, 342.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Michigan Historical Collections, 11:370-371.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., 11:374.

[20] Ibid., 20:30-132.

[21] Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 174.

[22] Samuel Hazard, ed., Pennsylvania Archives (Philadelphia: Joseph Severns & Company, 1854), 1st Series, 10:85-86.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid., 10:88-90; Michigan Historical Collections, 20:147.

[27] Michigan Historical Collections, 20:147.

[28] Ibid., 20:177.

[29] Ibid., 20:179.

[30] Ibid., 20:183.

[31] Timothy J. Shannon, Iroquois Diplomacy on the Early American Frontier (New York: Penguin Books, 2008), 194.

[32] The committee consisted of James Duane, Richard Peters, Daniel Carroll, Benjamin Hawkins, and Arthur Lee.

[33] Gaillard Hunt, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922), 25:680-689.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Neville B. Craig, ed., The Olden Time: A Monthly Publication Devoted to the Preservation of Documents (Pittsburgh: Wright & Charlton, 1848), 2:418.

[36] Ibid., 2:424.

[37] Ibid., 2:426.

[38] Ibid., 2:421-422.

Recent Articles

Thunderstruck: The Treaty of Paris Reaches the Frontier

On This Week’s Dispatches: Blake McGready on the Continental Army in the Hudson Highlands

Quotes About or By Native Americans, 1751 to 1793

Recent Comments

"Dr. James Craik and..."

Three of the doctor's homes are still extant in Alexandria, Va.

"The Soldiers Fell Like..."

Hi Mr. Barbieri, Thanks for your comment and reading the book review...

"A Rhode Island Officer’s..."

There is a very detailed and lengthy (250 pages incl. 90 pages...