The Continental Congress received the preliminary peace treaty on March 13, 1783, proclaimed a cessation of hostilities on April 11 and ratified the preliminary peace treaty on April 15.1

Three days later, in general orders issued at Newburgh, New York, Washington announced that an armistice would go into effect at noon on April 19, the eighth anniversary of the war’s outbreak at Lexington and Concord.2 The armistice heightened a sense of urgency that had been building among the Continental Army’s officers since the fall of 1780, when they threatened to resign en masse if Congress did not find a way to recognize their contribution to the war. On October 21, 1780, Congress promised that they would receive the same retirement terms as their British counterparts, that is, half pay for life. 3

By the fall of 1782, Congress had made no plans to implement the promise; in fact, Robert Morris, the Superintendent of Finance, stopped all pay as a cost-savings measure. Morris’s position was that the soldiers’ pay had to come from requisitions and because the states had not complied with Congress’s requests, the troops could not be paid. He wrote, “[The states] have been deaf to the calls of Congress, to the clamors of the public creditors, [and] to the just demands of a suffering army.”4 In late December of 1782, three officers, Gen. Alexander McDougall, Col. John Brooks, and Col. Matthias Ogden travelled to Philadelphia to lay the army’s grievances before Congress. It would not be until January 6 that they were able to present their petition:

Our situation compels us to search for the cause of our extreme poverty … We have borne all that men can bear – our property is expended – our private resources are at an end, and our friends are wearied out and disgusted with our incessant applications. We, therefore most seriously and earnestly beg, that a supply of money may be forwarded to the army as soon as possible. The uneasiness of the soldiers, for want of pay, is great … We regard the act of Congress respecting half-pay, as an honorable and just recompense for several years of service … We see with chagrin the odious point of view in which citizens of too many states endeavor to place the men entitled to it … We have reason to believe that the objection generally is against the mode only. To prevent therefore, any altercations and distinctions … we are willing to commute the half-pay pledged for full pay for a certain number of years.5

They were not only concerned about their pay that was months in arrears, but also whether their pensions would be provided as promised. Congress established a committee to address their proposal.

Matters became worse, however, on January 24, when Robert Morris tendered his letter of resignation effective the beginning of May. With the arrival of the preliminary peace treaty, the officers’ patience had all but run out. Between March 10 and 15, everything came to head at the army’s Newburgh cantonment. On March 17, Alexander Hamilton wrote to Washington, “We have Eight states and a half in favour of a commutation of the half pay for an average of ten years purchase, that is five years full pay instead of half pay for life.”6 Within a week, Hamilton was able to convince Congress to accept the commutation with an additional six percent interest. On March 24, Congress approved the commutation.7 On April 9, Robert Morris informed the congressional committee that, in accordance with General Washington’s recommendation, three months pay would be granted to each soldier and officer at the time of their discharge. The problem was that there was not nearly enough money in the treasury to cover the expense. Morris agreed to issue notes bearing his name with due dates of six months to cover the shortfall.

In issuing my Notes to the required Amount it would be necessary That I should give an express Assurance of Payment: And in so doing I should [be answerable] personally for [the money] when I leave the Office and depend on the arrangements of those who come after to save me from Ruin 8

The person authorized by Robert Morris to settle all of the army’s accounts was John Pierce, Paymaster General.

As early as May, proposals and counter proposals had been exchanged between General Washington and the Congress as to the composition of the peacetime military. Although Washington’s initial plan was for a permanent army of 3000, it exceeded the desires of the ever cost-conscious Congress who decided instead to furlough those men who were enlisted for the duration of the war. They could always be recalled quickly if hostilities resumed.9 After Robert Morris worked out the details related to his notes with Congress, he had to have them printed and signed. The process took so long that that the notes did not reach the soldiers until June 7; this was five days after Washington issued general orders announcing that most of the army was to be furloughed. A few weeks before the issuance of the general orders, army contractors had arrived in camp with a supply of goods and sold them to the soldiers on credit. When Paymaster General John Pierce arrived with the notes, the soldiers, in order to pay their obligations, signed them over to contractors at a forty to fifty percent discount. This was due in some degree to contractor speculation but mainly because the Morris notes were warrants in anticipation of revenue. Many soldiers would head home with few or no notes in their pockets.10

The remaining army was comprised of men who had enlisted for three years after 1780 and those whose shorter-term enlistments had not yet expired. The 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th Massachusetts regiments were placed on furlough on June 12, 1783.11 The two New Hampshire units were consolidated into the single New Hampshire Regiment and served until January 1, 1784. The short-term enlisted men of the Rhode Island Battalion continued until Christmas Day. The men enlisted for the duration of the war in the five Connecticut Line units were furloughed in early June; the remaining short-term enlistments were consolidated into the 3rd Connecticut which was re-designated The Connecticut Regiment and served until the end of December.

The final peace treaty with Great Britain was signed in Paris on September 3. On October 18, the Continental Congress resolved that the Continental troops on furlough were to be discharged on November 3.12 The 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th Massachusetts regiments were the last to be formally discharged.13

On November 21, the British planned to begin the evacuation of New York City. Gen. Henry Knox, wanting to take back areas around the city as soon as they were vacated on the 16th, ordered Col. Henry Jackson with the 1st and 4th Massachusetts regiments ”to march this day for King’s Bridge at which place are the Light Infantry commanded by Lt. Colonel William Hull.”14 They were to secure the post as well as the north end of York Island. Knox said he would arrive at King’s Bridge either on the 19th or 20th; after which he and Jackson would march to New York City where they would await the arrival of General Washington.

After seven years of occupation by the British, New York City was reclaimed by General Washington and the Continental Army on November 25. As the British soldiers departed the city on the southern end of Manhattan Island, the American force entered the city on the northern end. Gen. Knox with Colonel Jackson’s regiment entered the city at noon. Leaving part of the regiment to secure the docks and main streets, Knox and Jackson rode to the Bowery just outside of the city to meet Washington. Colonel Jackson’s Regiment formed up on Bowery, eight men abreast. When Washington arrived, he moved to the head of the column and with Governor Clinton, Lt. Gov. Pierre van Cortlandt, Henry Knox, and Henry Jackson marched into the city.

On December 3, one day before taking leave of his officers at Fraunces Tavern in New York, Washington ordered Knox to reduce

to one [Corps consisting] of 500 R[ank] and F[ile] … these Men should be selected generally from those who have the longest term to serve, and that the remainder should be discharged as soon as the circumstances will permit … The present Corps of Artillery, may be reformed and arranged in Companies, upon the bef[ore ment]ioned principles … The purpose for which these troops are retained, is, for the securi[ty of the Post] and Stores at West Point and its dependencies and the Stores in general ….15

Capts. Israel Frye and Joseph Potter’s New Hampshire companies, the Massachusetts men with the longest remaining times, Capt. John Doughty‘s Company of the 2nd Continental Artillery Regiment from New York, and the remaining officers and men of the Corps of Invalids16 became Colonel Henry Jackson’s American Regiment. The officers of the Regiment were Col. Henry Jackson, Lt. Col. William Hull, Maj. Caleb Gibbs who was made brevet lieutenant colonel on September 30, 1783, and Capt. Job Sumner who was made brevet major on the same date. The four officers would serve until June 20, 1784.17

Maj. General Benjamin Lincoln tendered his resignation as Secretary of War on October 29 and it was officially accepted on November 2, 1783.18 Knox had been considered for the position when it was given to Lincoln in 1781, and expressed his interest in succeeding him when the time came. Even though Lincoln and Washington recommended him, Congress chose not to fill the vacancy. The official reason was that Knox had acquired a ‘special professional knowledge’ as head of the artillery branch and that he could not be spared; the unofficial reason was that Congress wanted the Secretary’s position to be filled by a major general; Knox was only a brigadier general. Washington, concerned about the conclusions Knox might draw wrote to him:

Finding it essential to [the] public interest that you should superintend the Posts and Military affairs in this Department; until some farther Arrangement or until the pleasure of Congress shall be known; I therefore request that you remain in Service until the foregoing events shall [be resolved].19

That same day, all the remaining Continental Army officers were invited to the farewell party that was being held in the Long Room of Fraunces Tavern. Just as the army had dwindled in size, only a handful of officers remained. Of the twenty-nine major generals commissioned by Congress during the war, only Knox, McDougall, and von Steuben were present. Most of the others had retired, resigned, or died. Of the forty-four brigadier generals, only James Clinton, brother-in-law of the governor, was present; only one colonel of the line was there, Henry Jackson, and only one lieutenant colonel, Benjamin Tallmadge.20

After Washington retired, Knox became the commanding general of the army. On January 3, 1784, he submitted to Congress a list of Continental army officers remaining in service, and a return showing the organization of Jackson’s Regiment. The regiment consisted of 775 officers and men:

Infantry: 1 colonel; 1 lieutenant colonel; 1 major; 9 captains; 9 lieutenants; 9 ensigns; 1 adjutant; 1 quartermaster; 1 paymaster; 1 surgeon; 1 surgeon’s mate; 1 sergeant major; 1 quartermaster sergeant; 1 drum major; 45 sergeants; 16 drummers and fifers; and 500 rank & file (corporals and privates)

Artillery: 1 major; 1 captain; 2 captain lieutenants; 7 lieutenants; 1 adjutant;

10 sergeants; 12 corporals; 2 bombardiers; 2 gunners; and

100 matrosses

Invalids: 4 captains; 4 lieutenants; 2 sergeants; 1 drummer; and 27 rank & file 21

He also informed Congress that his regiment was now guarding not only West Point, but one infantry company was guarding the military stores in Springfield, Massachusetts, one artillery company was serving in New York City until the powers of civil government were fully established, and another company of artillery, currently at Albany, was moving to Fort Schuyler.

On January 29, 1784, when Knox learned that Congress was planning to revise the War Office and was considering the use a standing militia force as a peacetime army, he resigned his commission, “well satisfied to be excluded from any responsibility in arrangements which it is impossible to execute.”22

The United States and Great Britain exchanged ratifications of the treaty on May 12, 1784. On June 2, 1784, Col. Henry Jackson’s Regiment was informed that they would soon be discharged:

Resolved, that the commanding officer be directed to discharge the several officers and soldiers now in the service of the United States, except 25 privates to guard the stores at Fort Pitt, and 55 to guard the stores at West Point and other magazines, with a proportionate number of officers; no officer to remain in service above the rank of a captain; those privates to be retained who are inlisted on the best terms; provided Congress, before its recess, shall not take other measures respecting the disposition of those troops.23

The remaining soldiers would be formed into one company under the command of New York Artillery Captains John Doughty and William Johnson. Doughty had been made a brevet major the previous summer.

On June 3, the final day Congress was in session, until October 30, it was determined that a regiment consisting of seven hundred men from the states of Connecticut, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania would be formed for securing and protecting the northwestern frontiers of the United States and for garrisoning the posts soon to be evacuated by British troops. Their pay, subsistence and rations were to be the same as had been allowed to the troops of the Continental Army. The commanding officer would be Lieutenant-Colonel Josiah Harmar, seconded by Captains John Doughty and William Johnson whose company was to be absorbed into Harmar’s First American Regiment.

Between the 13th and the 20th of June, the companies of Henry Jackson’s

Regiment turned in their arms and equipment, marched to the ferry and crossed to the eastern bank of the Hudson where they received their discharge papers.24

On June 20, 1784, the Continental Army no longer existed.

1 Mark M. Boatner, III, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (New York: David McKay Co., Inc., 1966), 847-49.

2 Henry B. Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution (New York: Promontory Press Reprint Edition, originally published 1877), 658.

3 Journals of the Continental Congress, 18:961.

4 Robert Morris to the Governors of the States, 16 May, 1782, in Francis Wharton, ed., The Revolutionary Correspondence of the United States (Washington DC: G.P.O., 1889), 5:423-24.

5 Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, from the Original Records in the Library of Congress (Washington DC: Government printing Office, 1907), 8:485 24:291-93.

6 Harold C. Syrett, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962), 3:290-93.

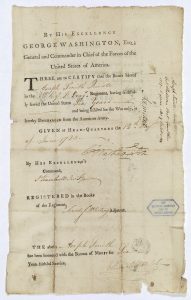

7 Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 24:207-10; “Continental Congress Resolution on Half-Pay, March 22,1783,” The Gilder Lerhman Collection, The Gilder Lerhman Institute of American History, New York, #GLC02437.02017.

8 Morris to Alexander Hamilton, Theodorick Bland, Thomas Fitzsimons, Samuel Osgood, and Richard Peters, April 14, 1783, in Syrett, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 3:323-25.

9 John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington, from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, Letterbook 16 (Washington DC: G.P.O., 1931-1944), 296.

10 John Pierce to Morris, July 23, 1783, in The Papers of the Continental Congress, No. 137, 2:717-18.

11 Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army (Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 1983), 207-10.

12 Wright, The Continental Army, 181.

13 Wright, The Continental Army, 207-10.

14 Henry Knox to Henry Jackson, November 16, 1783, in the Gilder Lerhman Collection, #GLC02437.10189.

15 George Washington to Knox, December 3, 1783, in Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, 367.

16 On June 20, 1777 the Continental Congress resolved “that a Corps of Invalids be formed … This Corps to be employed in garrisons, and for guards in cities and other places, where magazines or arsenals, or hospitals are placed.” Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 8:485.

17 Francis Bernard Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775 to December, 1783 (Washington DC: Nichols, Killam & Maffitt, 1892), 55; Janice E. McKenney, compl., Field Artillery – Regular Army and Army Reserve (Washington DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1985), 70; Fred Anderson Berg, Encyclopedia of Continental Army Units: Battalions, Regiments, and Independent Corps (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1972), 55.

18 Washington to Knox, November 2, 1783, Founders Online, National Archives. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-12009.

19 Washington to Knox, December 4, 1783, Founders Online, National Archives. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-01-12141.

20 William Gardner Bell, Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff, 1775-2005: Portraits & Biographical Sketches of the United States Army’s Senior Officer (Washington, DC: Center of Military History; United States Army, 1983), 54.

21 Thomas H. S. Hamersly, ed., Regular Army Register of the United States for one Hundred Years (Washington DC: T. H. S. Hamersly, 1881), 41-43; William E. Berkhimer, Historical Sketch of the Organization, Administration, Material and Tactics of the Artillery, United States Army, Appendix A 14 (New York: Greenwood Press, 1968, originally published 1884), 349.

22 Harry Ward, The Department of War, 1781–1795 (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1965), 4.

23 Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress, 27:512.

24 Wright, The Continental Army. 180.

One thought on “Furloughs, Discharges and the End of the Continental Army”

Excellent article. One small point to correct. It was Captain Isaac Frye, not Israel. Frye and Potter had responded to the April 19, 1775 Alarm and both enlisted on April 23, 1775; Frye as a second lieutenant and Potter as a private. Of the New Hampshire men, Ensign John Rowe, who also enlisted as a private, was the only other having served the same length. Frye was breveted a major on 27 Nov 1783 (the original document is in the collections of the New Hampshire Historical Society).