Cartoons were a vital part of England’s print media in the 1770s, and were almost exclusively of the sort that today we call editorial cartoons. Artists drew images packed with symbolism expressing opinions concerning current events. Sometimes they included word balloons and captions in prose or verse, but many were simple images that left the reader to interpret and understand the message. Engravers rendered them and printers sold them to eager readers.

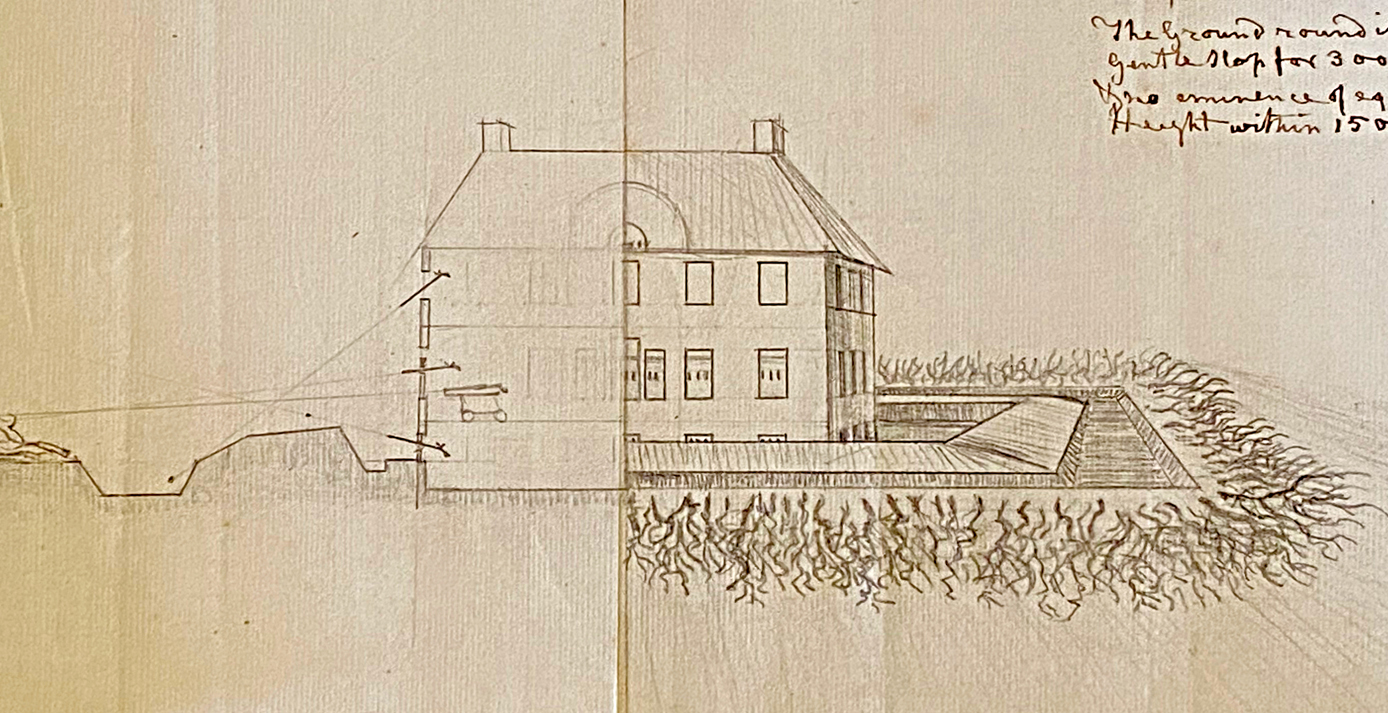

The image here was published in London in 1778 and is currently in the Library of Congress. It presents a cynical view that the war in America was far from being won in spite of British military victories. In the center is a proud officer – General Sir William Howe, perhaps – presenting his compliments to a man on the left who may represent King George III. On the right, a cocky British soldier shows off three motley American captives, while a black man lies wounded on the ground that is littered with spent cannonballs. But in the background looms a mighty American fortress still unconquered.

The satire is evident, but the image holds information of interest for other reasons. It gives a rare depiction of a British soldier on campaign, wearing a single-breasted jacket, trousers and a jaunty round hat with one side turned up and adorned with a feather, rather than the more formal uniform seen in pictures of soldiers in Great Britain; it correlates with other pictures and documentary sources for campaign clothing. The American soldiers, too, are dressed in an assemblage of garments which, although cartoonish, jibes with other information about Continental army clothing. These details suggest that the original image was drawn by someone who’d served in the British army in America, possibly the caricaturist Lieutenant Richard St. George Mansergh St. George of the 52nd Regiment of Foot who had been severely wounded at the battle of Germantown and was, in 1778, back in Great Britain recovering.

12 Comments

Like all good satire/political cartoons, there seems to be no shortage of interpretations.

For one, I’ve always interpreted this image was meant to be cynical of the American forces–that the soldier on the ground wasn’t wounded by lying prostrate, indicating submission (and thus was a metaphor for slavery) to wealthy officers who remained better equipped and well-to-do and standing in sharp contrast to the poorly equipped Continental troops.

The Library of Congress offers this interpretation:

“Print shows an African man lying on the ground, wounded by cannon shot, over him are standing several men, on the left is a congressman clearly suffering from a visual disorder (strabismus or walleye and also, perhaps, blindness to the needs of the military), center is a military officer gesturing with his tricornered hat to the wounded soldier while looking at the congressman. On the right is a well dressed soldier mocking three disgruntled, ragged soldiers. In the background is a fenced area labeled “US”, on a hill above is a fort, presumably British, from which a soldier fires cannons upon the enclosure from which soldiers are apparently retreating toward a palisade.”

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004672627/

Yale also offers this interpretation:

“A scene before an American fort and palisade, perhaps depicting the indifference of Congress to the sufferings of American soldiers and the pro-slavery attitude of the Americans. A black man lies wounded in the foreground, surrounded by cannon balls. An officer gestures towards him with his hat, turning to a man on the left (possibly meant to represent a Congressman) who is wearing a fur coat, large feathered hat, and is smoking a pipe. To the right of the officer an American soldier points and smiles towards three “Death or Liberty” men, all with grim features and ragged clothes.”

http://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:291733

Can someone comment on “Death or Liberty” men. Patrick Henry gave his speech in 1775. Did this “battle cry” carry throughout the war? The scene is from 1778, three years later. Was “Death or Liberty” men some kind of common derogatory remark or just a label for the cartoon?

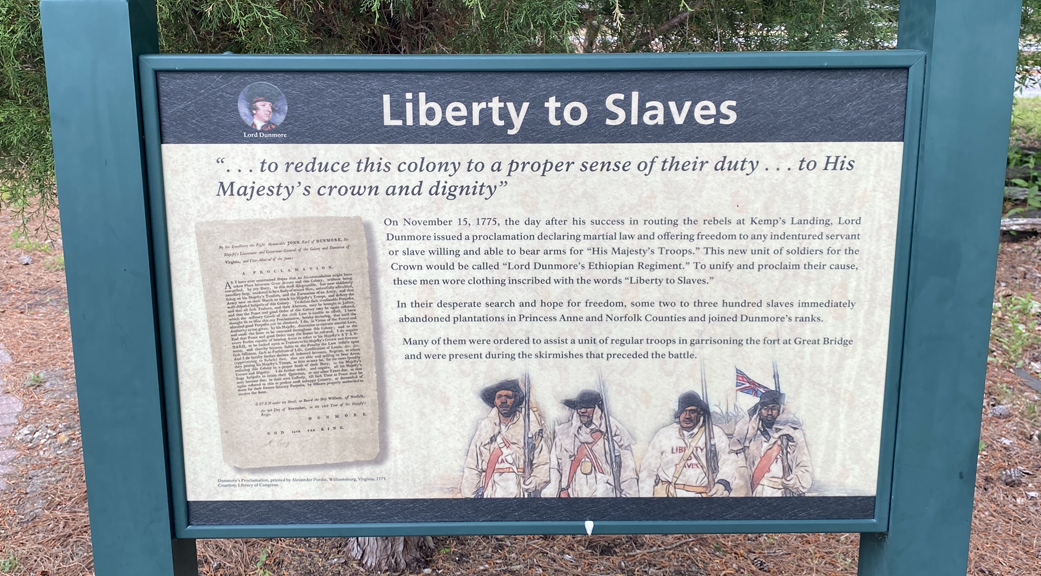

“Liberty,” per se, did NOT equate with our modern day interpretations of concepts such as freedom or independence. Liberty in the eighteenth century was a reference to being able to pursue the possession of “property,” itself something different from what we consider its meaning today. Then, property was the entire basis of the law, going back centuries in English history, and meant both the tangible and the intangible (such as possession of a public office). Liberty and property were locked together and could not be separated out from each other.

So, if government interfered with the possession of property, it was also impinging on liberty at the same time, which was the colonists’ viewed as their very reason for existence. All of this was protected, in turn, by access to the rule of law, which the colonists believed was allowed them, as Englishmen, to the same extent that those back in the homeland could obtain it. London did not agree, as Parliament was then coming into its own as the supreme provider/interpreter of law, and, incidentally, further diminishing the prerogative.

Between 1768 and 1774, the times presented them with the presence of a dreaded British “standing army,” enforcing, in part, Parliament’s Coercive Acts brought into existence by a body that did not represent their concerns. It was the culmination of the ongoing problem presented by dueling interests, the existence of a British constitution, the various colonial constitutions, and the overall imperial constitution that tied it all together.

“Death or liberty” was a shorthand way of describing the importance that these issues presented. Of course, in the context of this image in a post-1776 world after the Declaration, one can begin to see that liberty was, perhaps, beginning to take on other connotations than what earlier generations understood it to be.

Thank you, Gary.

I don’t know what you just did to me but a lot of knowledge I didn’t know I had just coalesced. Words like Zeitgeist and Social Paradigm pop into my head and I am recalling conversations with a Sociology professor about judging men from the perspective of their time and not ours.

There are several well-documented instances of “Liberty”, “Liberty or Death” and other variations appearing on uniforms of American troops early in the war. The extent to which this was still being done by 1778 is difficult to say, but this 1778 British cartoon used memes that were well established in the popular media. Even if American troops were no longer putting these slogans on their uniforms, it was an easy way for an artist to signify to a British audience that the downtrodden troops were American soldiers.

Thanks Don. I was not aware they actually wore these slogans on their uniform. I should read more about the war from the British perspective as I am learning that there was perhaps more sympathy for the Americans among the British populace than I thought. All of you at the Journal do an excellent job of dusting off old text book history and sharing it through the eyes of those that lived it. Most enjoyable.

Here is a nice description of Francis Marion from William Dobein James 1821 sketch of Marion’s revolutionary career in 1780 – 1782. Note the reference to ‘Liberty or death’ on his uniform.

48 years of age and below average in height, “his body was well set, but his knees and ankles were badly formed; and he still limped upon one leg. He had a countenance remarkably steady; his nose was acquiline, his chin projecting: his forehead was large and high, and his eyes black and piercing.”

“He was dressed in a close round-bodied crimson jacket, of a coarse texture, and wore a leather cap, part of the uniform of the second regiment, with a silver crescent in front, inscribed with the words, ‘Liberty or death’.”

I just glanced at the Southern Campaigns site and see that Captain Charnal Durham W9418 had a plate in his cap having the motto inscribed “Liberty or Death” and that Zela Reno W8545 had a purple hunting shirt marked in the breast in large letters with the words “Liberty of death” with a “Mecaroni” hat and buck tail.

I have another interpretation of this cartoon– I think the bundled up man on the left is Baron Von Steuben, and he is on his *first inspection* of the Continental Army’s shivering soldiers at Valley Forge. The year 1778 matches up– and this image of Von Steuben matches pretty well to the statue at Valley Forge. The two men in the center are most likely Von Steuben’s ‘retinue’ of two young men traveling with him as aides (there were apparently at least rumors at the time — run with by many today — that Von Steuben was gay…. I’m not taking sides on that issue…but the fact that these 2 younger men look *not American* and not as old as Von Steuben, I think helps substantiate my interpretation). What do you all think?? I had a student in my AP US History online class do a cartoon analysis of this image, and he was totally befuddled at all the varied interpretations ‘out there’– he could make little sense of it… and neither could I, until I thought of Valley Forge in winter of 1778.

It is true that there are other interpretations of this print. Like many aspects of the American Revolution, there are “standard” interpretations such as those offered in the Library of Congress and the Yale catalogs, and there are “modern” interpretations such as the one here. For a detailed discussion of the “modern” interpretation, see “A New Appraisal of an Old Print,” Stephen Gilbert and Stephen Rayner, The Valley Forge Journal Vol. 3 No. 2 (December 1986), 92-103.

Thanks Don! I’m very interested in this new interpretation. I don’t mind it when old standards are shaken up–keeps things interesting and people honest.

Just wanted to insure the Culpeper(VA) Minutemen got their share of exposure. They wore “Liberty or Death” on their hunting shirts for about a year until disbanded. This link provides their brief history:

http://cmmsar.com/history.html