But what still hightens our Apprehensions is that those unexpected proceedings may be preparatory to new Taxations upon us: For if our Trade may be taxed why not our Lands? Why not the produce of our Lands and every Thing we possess or make use of? This we apprehend annihilates our Charter Rights to Govern and Tax ourselves.–It strikes at our British Privileges which as we have never forfeited them we hold in common with our Fellow Subjects who are Native of Britain.

-Town of Boston to its Representatives in the Massachusetts Bay General Assembly, May 24, 1764

250th Anniversary of the Stamp Act

2015 marks the 250th anniversary of the Stamp Act and its passage. In recognition of the important role the act played in the American Revolution, the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library created a traveling exhibition: We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. The exhibit features pieces from the library’s collections as well as items loaned from other institutions, including Colonial Williamsburg, the Library of Congress, the British Library, and other organizations. We Are One opened at the in the McKim Gallery at the Boston Public Library on May 2, 2015.[1]

The Stamp Act: An Overview

Great Britain stood victorious at the end of the French and Indian or Seven Years’ War (1754-1763). The Treaty of Paris 1763 brought peace and confirmed that all lands in North America, east of the Mississippi River, belonged to the British Empire. With the troublesome boundary between New France and the British North American colonies dissolved, it seemed as though North Americans might witness a lasting peace.

Victory came at a high price. Great Britain borrowed large sums to wage the Seven Years’ War and by 1764 its national debt had risen from approximately £73,000,000 in 1755 to about £137,000,000. Furthermore, Great Britain did not intend to allow France or Spain to reclaim the parts of North America they had lost. The British government resolved to keep a force of 10,000 regular soldiers in North America to protect its subjects and territories. Government officers estimated that the annual cost for these 10,000 soldiers would exceed £220,000 per year.[2]

In April 1763, George Grenville became the First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer. Grenville intended to raise monies for America from America. He did not expect the colonists to pay for anything more than their own defense, and he did not even intend for them to pay for their whole defense. Traditionally, Parliament had raised money in the colonies through requisitions. It sent requests to each colonial governor and asked him to see to it that his colonial assembly raised the desired funds. Although this had been Parliament’s traditional course, requisitions often proved to be time consuming and unreliable. Grenville needed to feed money into the Treasury as soon as possible so he turned his attention to the regulatory laws Parliament had already passed. Parliament had long passed laws and customs duties to regulate trade throughout the empire. However, when Grenville examined the Treasury’s accounts he found that customs collectors in North America had not enforced these laws; North American customs duties brought the Treasury only about £1800 per annum.[3]

In 1764, Grenville asked Parliament to pass what became known as the Sugar Act. The law imposed trade duties on madeira, coffee, foreign indigo, and foreign sugar. The act also imposed a tax of three pence per gallon on molasses. The law enraged many colonists, especially the tax on molasses. The colonists had expected a one pence per gallon tax; three pence per gallon seemed too high to support given the postwar economic depression. The colonial assemblies sent written protests to Parliament, but no riots erupted. Few colonists questioned Parliament’s right to regulate trade and impose customs duties as a part of that regulation. The Sugar Act was a regulatory act, not an act of taxation.

When Grenville asked Parliament to pass the Sugar Act, he also hinted that he wanted to impose a stamp duty in 1765. In private conversations with lawmakers and colonial agents, Grenville stated that he intended to give the colonies a year to impose taxes upon themselves before Parliament levied taxes upon them. Colonies such as Massachusetts and Virginia wrote to their colonial agents in London to find out how much revenue Grenville wanted the colonies to raise, but Grenville refused to answer. His refusal to state specific amounts suggests that Grenville did not intend to allow the colonies to avoid Parliamentary taxation. Additionally, when Grenville asked Parliament to pass the Stamp Act, he asked them to do so without reading the petitions, protests, and other documents several colonies had sent against the measure.

On March 22, 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act. The act contained fifty-five resolutions which enumerated documents that had to be written or printed on paper embossed with a stamp from the Treasury Department: fifteen classes of court documents, papers for clearing ships from harbors, college diplomas, public office appointments, bonds, land grants and deeds, mortgages, leases, indentures, contracts, bills of sale, articles of apprenticeship, liquor licenses, playing cards, dice, pamphlets, newspapers, newspaper advertisements, and almanacs. Attorney licenses bore the highest tax at ten pounds sterling while other taxed papers and goods ran from three pence to ten shillings. All stamped items had to be paid for in sterling and all proceeds would be used to procure supplies for the soldiers stationed in North America.

The Stamp Act reignited the age-old dispute of the colonists’ place within the British Empire. Most colonists argued that they stood equal with their fellow countrymen in the United Kingdom in terms of rights and privileges. These rights and privileges included the right for the colonists to be taxed only by their elected representatives. Grenville and others argued that the colonists and the colonies stood subordinate to Parliament and the United Kingdom. They believed that Parliament had the right to tax the colonies because the diversity of interests among the members of Parliament meant that the views of everyone in the empire received representation. Disagreement over the right of Parliament to tax the colonies caused violent protests to erupt throughout British North America over the Stamp Act. Questions over taxation and the colonists’ place within the empire continued until 1776 when the Continental Congress decided that the thirteen British North American colonies “are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.”[4]

We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence

We Are One seeks to explore the “tumultuous events that led thirteen colonies to forge a new nation” and to “change the way people look at the Revolutionary War” by exhibiting maps and artifacts from about 1750 to 1800. The exhibition presents different views of the British Empire and a cartographic timeline of the American Revolution. It begins with images of Boston in the 1760s and 1770s. The maps, political cartoons, and sketches within this section of the exhibit depict how Bostonians saw their place within the British Empire. A sketch of the scene of the Boston Massacre, likely done by Paul Revere, reveals not only the massacre, but the placement of imperial buildings in Boston. We Are One curators believe that John Adams, Josiah Quincy Jr, Robert Achmuty, Samuel Quincy, and Robert Treat Paine used the drawing during the British soldiers’ trials.[5] The sketch notes the positions of the victims and uses letters and numbers to mark the position of key players and evidence.

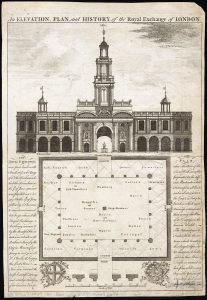

From Boston, We Are One invites you to view the empire the way Britons did after 1763: through maps and drawings. An Elevation, Plan, and History of the Royal Exchange of London offers you a unique opportunity to view the postwar British Empire and the North American colonies’ place within it. Under the elevation of the Royal Exchange building, the artist drew a floor plan of the interior of the Exchange. The center of the floor plan depicts the trades and places most important to the economic well-being of the empire: Ship-Brokers, “Dyers & Bays-Factors,” “Druggists & Grocers,” Sailors, “Silkmen & Silk Throwsters,” Clothiers, “Italian,” “Dutch,” and “Hamburg” form an inner circle of sorts around the central players. Portugal, Jamaica, Barbados, “French,” and Turkey lay just to the outside of the inner circle with “East Country,” “Irish,” “Scots,” Jewellers, “Armenian,” Jews, “Spanish,” Virginia, Carolinas, New England, and Norway occupying the fringes of the building. The British American colonies of the mid-Atlantic are conspicuously absent.

As you make your way through the exhibition, you will notice that the maps and artifacts on display move from a peaceful British Empire toward the violence and wars that drastically changed the geographic landscape of it. The French and Indian War altered the world map as European empires gained and exchanged territories. In North America, Great Britain acquired the lands occupied by New France and Florida. Battle maps from the war, such as Samuel Blodget’s A Prospective View of the Battle Fought Near Lake George, invite you to picture the scale of the war and the numbers of troops involved.

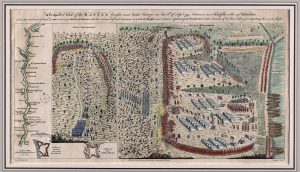

The Blodget map depicts the Battle of Lake George. On September 8, 1755, Colonel William Johnson led approximately 2,000 British soldiers and 250 Mohawk warriors into battle against Baron Dieskau’s French and Indian force numbering about 2,500 men.[6] Blodget contextualizes the importance of this battle map by portraying the geography of New York. On the far left, he sketched the Hudson River from Lake George to New York City. The names of sizeable settlements and fortifications appear along the river. To the right of the river, Blodget depicts the first and second engagements of the battle. He marks the position of each army with small soldiers; the small size of the soldiers provides scale to the battle (thousands of men participated) while Blodget’s attempt to make the soldiers appear three dimensional reflects that the soldiers were real people who fought and died during the action. Blodget also illustrates the war materiel. The British Army used thousands of tents, bateau, cannon, muskets, and flags to wage the war, signs of the valued assistance provided by the home front.

The War for American Independence also altered the map of the British Empire. A magnificent map of the Battle of Bunker Hill contains an overlay that shows the placement of troops and their lines of attack.[7] Like many military maps, the cartographer of this map intended for his work to relate the story of the battle as well as serve as a study guide for military personnel. This part of the exhibit also provides you with a chance to compare and contrast maps and mapmakers. Polish military engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko crafted a map of the Plan of the battles of Saratoga (1777). Parisian cartographers Esnauts and Rapilly produced Carte de la patrie de la Virginie ou l’armée combinée de France & des États-Unis de l’Amérique a fait prisonnière l’armée anglaise commandée par Lord Cornwallis le 19 octobre, 1781: avec le plan de l’attaque d’Yorktown & de Glocester or Map of the Country of Virginia where the combined army of France and the United States of America made prisoner the English army commanded by Lord Cornwallis the 19 October 1781: with a plan of attack of Yorktown & of Glocester. Collectively these maps offer an opportunity to view and compare international perspectives on the war.

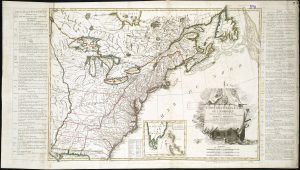

The exhibition concludes with maps and artifacts that reflect peace and the new nation. Jean Lattré’s Carte des Etats-Unis de l’Amerique suivant le Traité de Paix de 1783 (Map of the United States of America following the Treaty of Peace of 1783) presents you with a view of the first map of the United States produced after the ratification of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Lattré frames the new nation with lists of the events that made its independence possible. Note the cartouche with the French warship bearing the title of the map (Carte des Etats-Unis) in its sails. It stands just off the coast and reflects how the French helped gave birth to the new nation.

We Are One also provides an opportunity for you to see several rarely shown maps and artifacts. Around 1876, the people of Boston purchased the first congressional medal from George Washington’s descendants. In 1776, Congress voted to present Washington with a medal for his success in evicting the British from Boston on March 17, 1776. It commissioned French engraver Pierre Simon Benjamin Duvivier to mint the medal, which he did in 1789. The front of the medal contains a bust of George Washington. Its back depicts Washington and the cannon brought from Fort Ticonderoga on Dorchester Heights.[8] The Boston Public Library rarely displays this one-of-a-kind object, but has agreed to exhibit it in We Are One.

We Are One has also borrowed several maps, drawings, and watercolors from King George III’s Topographical Collection at the British Library. A gorgeous watercolor titled View of Boston the Capital of New England from Col. Hatch Made on the Road in Dorchester is among the borrowed items. The watercolor provides detailed views of Boston and its harbor islands from seven different perspectives. Given the fragile nature of this watercolor and its sensitivity to light, this particular artifact will only be displayed from May until about July or August 2015.

We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence offers history lovers a unique and multifaceted way to view the history of the American Revolution. You can view the exhibition at the McKim Exhibition Gallery in the Boston Public Library, free of charge, from May 2 to November 29, 2015. In February 2016, this traveling exhibition will open at Colonial Williamsburg, where it will remain on display until January 2017. We Are One will end its journey at the New York Historical Society where it will be open from April through August 2017.[9]

SPECIAL EVENT: Join Journal of the American Revolution for a private tour of this map exhibit on Saturday, May 9. Click here for details.

[1] Conor Yunits, “Press Release: Leventhal Map Center to Open American Revolution Exhibition,” April, 2015.

[2] Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766, First Vintage Books Edition (New York: Vintage Books, 2001); Edmund S. Morgan and Helen M. Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (Chapel Hill; London: The Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1995); Thomas P. Slaughter, Independence: The Tangled Roots of the American Revolution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2014).

[3] Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 21-40; Slaughter, Independence, 213-227.

[4] Anderson, Crucible of War, 641-687; Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789, vol. 3, The Oxford History of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982) 70-117; Continental Congress, “Declaration of Independence,” The Charters of Freedom: A New World Is at Hand, July 4, 1776, http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_transcript.html; Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, Slaughter, Independence, 209-279; Abigail L. Swingen, Competing Visions of Empire: Labor, Slavery, and the Origins of the British Atlantic Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

[5] John Adams. “Boston Massacre Trial Notes.” Boston Public Library Photostream, n.d. https://m.flickr.com/#/photos/boston_public_library/sets/72157623742255962/; John Adams, “Notes on the Boston Massacre,” Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, n.d., http://www.masshist.org/database/1744; Hiller B. Zobel, The Boston Massacre (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996).

[6] Samuel Blodget. “A Prospective View of the Battle Fought near Lake George.” Engraving, Hand Colored. London, 1756.

[7] The Battle of Bunker Hill took place on June 17, 1775 in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

[8] In May 1775, Patriots led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold had captured Fort Ticonderoga and its military stores from the British. Henry Knox led men and oxen from Ticonderoga to bring much needed artillery to Boston. The effort required a grueling march up and over the Berkshire Mountains.

[9] You may also view portions of the exhibit from the comfort of your home by visiting the We Are One digital exhibition: http://maps.bpl.org/WeAreOne

2 Comments

Elizabeth,

Thank you for sharing this information as it certainly sounds like an incredible exhibition; one I am in great hopes of being able to attend. For those of us that like to actually hold books in our hands and not look at computer screens, will there be any publication (i.e., a coffee table book) that highlights these most interesting artifacts?

Thanks Elizabeth for sharing important background details re BPL’s featured events & artifacts and for your comments on the exhibition. Might you recall if any of Jonathan Carver’s maps were included – of particular interest is Carver’s “Travels through the interior Parts of North America …”?