Following their victory at the Battle of Long Island (Brooklyn) on August 27 1776, the British established their headquarters in New York City where it remained throughout the war. They extended their control eastward into Long Island, intending to use it as a combination barracks, larder, and fortress. The British studded the Island’s northern shoreline with fortifications intended to enforce the British occupation, shield their Manhattan nerve center from attack from the east, and launch attacks against rebel held ports across Long Island Sound in Connecticut.

Some of these forts were manned only briefly, others more or less permanently. Due to its distance from New York City and its heavily Whig population, Suffolk County, comprising the eastern two-thirds of the Island, posed the greatest challenge to the British. Ultimately the British constructed a number of forts in, or near, the western sections of the County, contenting themselves in mounting foraging – effectively plundering – expeditions further east after their Sag Harbor base was destroyed by Return Jonathan Meigs in 1777. The key British bastions were constructed in the fjord-like harbors set along the north shore of Huntington and Oyster Bay in neighboring Queens County. Beginning in 1777, Lt. Colonel John Graves Simcoe turned Oyster Bay village into an armed camp, and used its harbor to ship out forage, food, and wood for the British army in New York City. Further east the British constructed Fort Slongo, and in 1780, established a new outpost, Fort St. George, at Mastic along the Great South Bay on Long Island’s south shore.

But the British presence in Suffolk was anchored by Fort Franklin, strategically positioned on a bluff situated on Lloyd’s Neck, a peninsula which extended northward from Huntington. Named for Benjamin Franklin’s Loyalist son, William Franklin, the fort controlled access from Long Island Sound into the waters of Oyster Bay and Cold Spring Harbor. Additionally, the fort’s garrison and guns, along with satellite encampments, provided protection for Tory raiders—the whaleboat men who descended on rebel towns across Long Island Sound in Connecticut. These guerrillas and plunderers camped in the woods and fields of east of Fort Franklin and used the inlet between the neck and the “mainland’ to shelter their watercraft.

Loyalists provided the bulk of the troops in the garrisons east of Queens County, and Fort Franklin was no exception. When it was established in 1778, the post was garrisoned by the third battalion (Ludlow’s) of General Oliver DeLancey’s Tory regiment who remained there until 1780.[1] In 1781 the Associated Loyalists, founded by the Fort’s titular namesake, made it their base of operations. Occasionally detachments from other units, such as the Loyal New England Regiment, a small group from Rhode Island, served at Fort Franklin.

Delancy’s men chose their spot well, constructing a formidable squarish earthworks surrounded by abbatis.[2] Fort Franklin was difficult to attack. Raiders attempting to take it from the west would have to come by sea, land on a narrow beach, and scale the high bluff on which it sat. The ground to the south fell off sharply creating an excellent field of fire, and the terrain to the north was almost as good. Only the level eastern approaches afforded any prospect of success, and even that was dubious due to the size of the garrison, which numbered 5-800 men. The strength of the fort, and its value to the British, is made clear by the fact that it remained in operation until the last winter of the war and was never taken—though not for lack of trying on the part of Revolutionary forces.

The land and waterways of Huntington, dominated by Fort Franklin, became a hive of Tory activity. The stronghold became an important element in General William Tryon’s raids on Connecticut coastal town in July 1779. Tryon’s attacks, part of General Henry Clinton’s plan to draw Washington out of the Hudson Highlands, began with an attack on New Haven on July 7. Three days later he landed at Fairfield, Connecticut and then crossed Long Island Sound to Huntington to refit and resupply.[3] On July 11 he appeared at Norwalk, Connecticut where he attacked and burned the town, before again returning to Huntington and the protection of Fort Franklin’s guns.[4]

Major Benjamin Tallmadge of the 2nd Continental (Connecticut) Dragoons was among those who witnessed Norwalk’s destruction. A native of Setauket, Long Island, Tallmadge, already running a major espionage ring in New York and Long Island, thirsted for opportunities to retaliate against British raids and shake their hold on his natal home. As he later recalled to his daughter, “I had long conceived the idea of capturing all these fortifications & driving the Enemy out of Suffolk County from which [they] drew such vast supplies of forage, grain and fresh meat.”[5] Fort Franklin, which anchored the British defenses in western Suffolk was a prime target. Tallmadge’s agents on Long Island kept him well-informed of British deployments and strength, and he wrote to General Robert Howe, commander of the revolutionary forces in Connecticut that he “intended to kill or take the whole gang of Marauders & Plunderers …which have for so long a time infested the coast on the sound.”[6]

On the evening of September 5, 1779 Tallmadge embarked a mixed force of 130 dragoons, boatmen and rebel refugees who had fled Long Island to Connecticut, across the Sound to Lloyd’s Neck where they made landfall about ten o’clock.[7] The raiders quickly captured two of the houses being used as quarters by the Loyalists, and then turned their attention to a number of huts which sheltered other enemy whaleboat men. Although some of the Loyalists resisted with musketry, Tallmadge’s men soon secured the entire encampment, scooping up prisoners, documents, and supplies. But whatever hopes Tallmadge held for capturing the fort and the guard on the isthmus connecting the neck to the mainland were dashed by the shooting which destroyed all hopes of surprise.

Having suffered no casualties himself, Tallmadge reembarked, taking his prisoners and booty, the latter of which would be sold and the proceeds distributed among the raiders.[8] His major regret was that a Tory captain named Glover, whom he identified as a major participant in British depredations in Connecticut, held British rank and could not be executed. He consoled himself that at least “one so atrociously guilty can be exchanged for some of our friends “in British captivity.”[9]

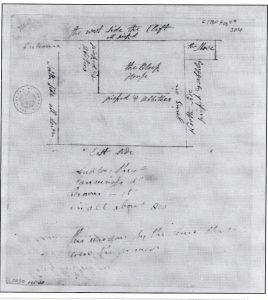

Tallmadge continued to distinguish himself in operations in the no-man’s land of Westchester County and on Long Island where he destroyed Fort St. George in 1780, and oversaw the capture of Fort Slongo the following year. But Fort Franklin remained the itch he could not scratch. In August, 1780, his main Long Island agent, Abraham Woodhull, sent him a detailed map of the fort, and he and General Samuel Parsons of the Connecticut militia, began planning a strike against the bastion. But concerns about the reliability of Parsons’ Long Island informants, later revealed as double agents, led Tallmadge to demur, and the raid was scrubbed.[10]

In the meantime, the “whaleboat war,” named after the vessels most often used by cross-Sound raiders from both sides, increased in volume and degenerated in nature. Using the maneuverable twenty foot craft, commonly equipped with a sail and swivel gun, rebel and Tory parties crisscrossed the marine no-man’s land of Long Island Sound to wreak havoc on their opponents. Some of the attacks were officially sanctioned, and had some military purpose, however much participants might have enjoyed punishing their enemy or enriching themselves in the process. More troubling were the growing number of raids mounted by freebooters taking advantage of the turbulent, sometimes near-anarchic situation, to engage in naked brigandage.

On September 23, 1780, Brigadier General Gold S. Silliman of the Connecticut militia sent a letter to Colonel G.G. Ludlow, commanding a battalion of DeLancey’s Loyalists at Fort Franklin, in hopes of suppressing the uncontrolled pillaging. “[T]his predatory kind of War I conceive,” Silliman wrote, “tends not in the least to close the great dispute between Britain and America.”[11] He proposed to suppress plundering expeditions from Connecticut if Ludlow would do the same on Long Island. Ludlow was willing to make the effort, but neither commander could make much headway against the numerous plunderers and personal score-settlers.[12]

In April 1781Tallmadge pushed Washington for permission to launch another raid against Fort Franklin. The commanding general had developed great confidence in the twenty-seven year old dragoon leader’s combat abilities. The previous summer he had authorized Tallmadge to restructure his dragoon troop as a semiautonomous legion (mixed horse and infantry.) He now readily acceded to Tallmadge’s request to storm the fort, but warned it should not be undertaken if the British fleet was in the vicinity. He suggested that Tallmadge confirm the enemy dispositions on Lloyd’s Neck, and then proceed to Newport, Rhode Island to arrange naval support from the French who were based there.[13]

On April 19, Tallmadge sailed across the Sound and met with his agents who provided him with fresh maps of Fort Franklin and Fort Slongo, as well as a return of Crown land and naval forces in the area.[14] In his report to headquarters, he estimated Franklin’s garrison at 800 men, “chiefly [Tory] refugees and deserters from the American Army” of whom 500 were properly armed.[15] The British stronghold was further protected by one sixteen gun vessel, two small frigates, and a galley. Tallmadge reckoned that if he could obtain the support of two French frigates they could secure the Sound crossings long enough for him to take both Fort Franklin and the smaller Fort Slongo about eight miles eastward.[16]

Back on the mainland and confident of success, Tallmadge sped off to Newport bearing “a very flattering” letter of introduction from Washington to the French. Both the Comte de Rochambeau, commander of the French Army, and Chevalier Destouches, his naval counterpart, were sympathetic, but the ships that might have made the venture possible were unavailable. Once again, Tallmadge found himself thwarted by the stronghold on Lloyd’s Neck.

Indeed, Fort Franklin had become an increasing cause of concern to revolutionary forces and civilians in Connecticut. In June, a recently formed Tory unit, the Board of Associated Loyalists, replaced Ludlow’s Regiment at the fort. Despite its corporate-sounding name, the Associated Loyalists, organized the previous November under the leadership of William Franklin, were keen for action, having already carried out raids on Norwalk, Branford, and New Haven early in the year. In June, the aggressive Tories struck anew near Guilford, Connecticut, and then captured a twelve-oared gunboat off Setauket, Long Island.[17]

American commanders determined to destroy the Tory stronghold, and this time they were successful in enlisting French aid. Tallmadge was away in Litchfield county procuring supplies for his men, and was not present when the allies made a fresh attempt on Fort Franklin. On the morning of July 10, a small French fleet of eight ships entered Huntington Harbor carrying a 450 man expeditionary force, mostly French, but including Americans, some who had been on previous raids with Tallmadge.[18] The troops, commanded by Baron Angelsy, landed on the east side of Lloyd’s Neck about 8:00AM and began the two mile march to the fort. Lt. Colonel Joshua Upham, Franklin’s commander, had been tracking the invaders since their ships first entered the harbor, and was ready to meet them when the Franco-American troops drew up in open ground 100 yards from the fort.

As the French and American troops slowly moved forward, Upham opened up with grape shot from his two twelve pound cannon. The volley, he reported to William Franklin, “threw them into confusion, and occasioned a very sudden, and I humbly conceive, very disgraceful retreat to their ships.”[19] Whether it was rational calculation or timidity, Angelsy, suffering three casualties, called off his attack and, as Upham observed, fell back to his ships and sailed up the Sound. The Loyalists suffered no losses, and Franklin remained defiantly in British hands.[20]

The British presence at Fort Franklin came to an end not as the result of revolutionary action, but as a consequence of the Crown’s decision to concede American independence. On August 2, 1782 Sir Guy Carleton, the latest British commanding general in America, informed Loyalist leaders in New York that a treaty granting independence was in the works. The effect on the Tory population was devastating, and the demoralization spread to Tory military units. Fort Franklin was no exception. Tallmadge received reports from his Long Island agents that Fort Franklin was in deteriorated condition with only about 200 men left in the garrison whose dwindling numbers were “without discipline.”[21] The fort received no supplies from the British commissary, and survived entirely on the illegal trade with Connecticut, a trade Tallmadge was striving to suppress. Despite their weakened and dispirited condition, the British kept an armed brig and galley in Huntington waters to protect the increasingly vital smuggling.

Sir Guy Carleton disbanded The Associated Loyalists in 1782 following a bitter controversy about their role in the execution of an American officer in New Jersey. Fort Franklin did not last much longer, and it was abandoned by the end of the year. There would be no more permanent British posts in Suffolk County, though in December 1782, a mixed forced of Tories under Benjamin Thompson occupied Huntington village and erected a redoubt atop the community burial grounds. Tallmadge organized an expedition to destroy it, but was stymied by rough seas in the Sound which forced him to abort the raid. By spring, Thompson had ridden away, and the British contracted their Long Island positions into Queens and Kings County, calling these in to Manhattan as they prepared for their final embarkation.

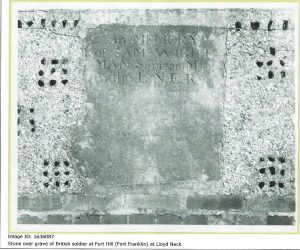

Little remains of the British forts on Long Island today. Anything of value on Fort Franklin was likely appropriated by local inhabitants, and all that remains is—maybe– one embankment wall, and the gravestone of a Loyalist soldier who had died there. The grounds, with spectacular views of Oyster Bay, Cold Spring Harbor and Long Island Sound, became the site of a large and opulent home known as Fort Hill House. But of the fort itself, there is barely a trace, and its role during the Revolution is little remembered today.

[1]William Kelby (ed.), Orderly Book of the Three Battalions of Loyalists Commanded by Brigadier General Oliver DeLancey, 1776-1778.1917, Reprint, (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc., 1972), x.

[2] Revolutionary War Papers, Huntington Town Archives.

[3] Mark V. Kwasny, Washington’s Partisan War, (Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1996), 244.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Letter, Benjamin Tallmadge to Mrs. Maria (Tallmadge) Cushman March 20, 1824 in “Personal Reminiscences of Major Benjamin Tallmadge.” Manuscript and Archives Division, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. New York Public Library, 187.

[6] Letter, Benjamin Tallmadge to General Robert Howe, September 6, 1779, Benjamin Tallmadge Collection, Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield Connecticut.

[7] Letter, Benjamin Tallmadge to General Robert Howe, September 6, 1779.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Tallmadge, Benjamin, Memoir of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge, Publications of the Society of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York, Vol. I (New York: Gillis Press, 1904), 51.

[11] Kwasny, Washington’s Partisan War, 277.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Letter, George Washington to Benjamin Tallmadge, April 8, 1781, http://www.familytales.org/dbDisplay.php?id+ltr_gwa4450.

[14] Letter, Benjamin Tallmadge to George Washington, April 20, 1781. BTC. LHS.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Tallmadge, Memoirs, 65.

[17] New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, July 2, 1781.

[18] Richard F. Welch, General Washington’s Commando. Benjamin Tallmadge in the Revolutionary War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014), 100.

[19] Letter, Joshua Upham to William Franklin, July 13, 1781 printed in New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, July 16, 1781.On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, http://royalprovincial.com/history/battles/aslep4.shtml

[20] Kwasny, Washington’s Partisan War, 298.

[21] Letter, Samuel Culper [Abraham Woodhull] to BT, July 5, 1782. George Washington Papers. Library of Congress.

2 Comments

It’s always enjoyable to read well-researched and written articles about the AmRev places where you grew up and this one was thoroughly enjoyable. I spent many years growing up on Long Island Sound which, from the standpoint of the War, allows you to experience much of what Richard portrays. On both the Westchester/Connecticut and Long Island shorelines, there were far too many inlets to protect yet many places to land a small to medium size raiding party. The Sound, even today, is notorious for its random currents, dramatic weather (including fogs) and water route to and from NYC. Even though most of the places are gone, in many instances modern place names honor the events of the Revolution, just like NYC and Boston. One of the reasons I enjoyed TURN so much is that is was located on eastern location and a viewer could appreciate the importance of Long Island Sound. If you drove around Oyster Bay and Huntingon there is an immediate appreciation of the strategic importance the North Shore (as we referred to it as party-seeking teenagers) held duriing the War and why this article resonates so much for me. Thanks for the great read.

Very nice article! Love the photo of Choke Point.

I’ve done my own research on Upham and the Associated Loyalists. They were quite a nuisance to Connecticut.

There is also some evidence that suggests an attack on Fort Franklin was being planned during the late summer of 1781 out of New London. But Arnold’s attack on its harbor and subsequent burning of some privateers being fitted out for the operation, forced them to cancel it.