It’s one thing to make speeches about declaring independence, or to assemble militias and discuss battle tactics against the enemy.

It’s quite another thing to pay for it all.

So how do you pay for a war that no one expected to last eight years?

Great Britain possessed world-wide colonies, tremendous wealth, the ability to tax its subjects, and excellent credit ratings in the well-established world credit market. But how did the fledgling American confederation of 13 states and a weak Congress go about funding their own rebellion?

History books and many teachers will imply that the French money and supplies before and after the Battles of Saratoga made all of the difference in America winning the war. While the French assistance certainly helped, it actually did a disservice to the Americans who basically paid for their own rebellion… the merchants, suppliers, planters and growers, average families, and of course the soldiers of the Continental Army. Let’s look at the total picture of how the War for Independence was paid for – 100 percent of which was paid for by Americans themselves through taxes, bonds, IOUs, and by paying off all foreign loans.

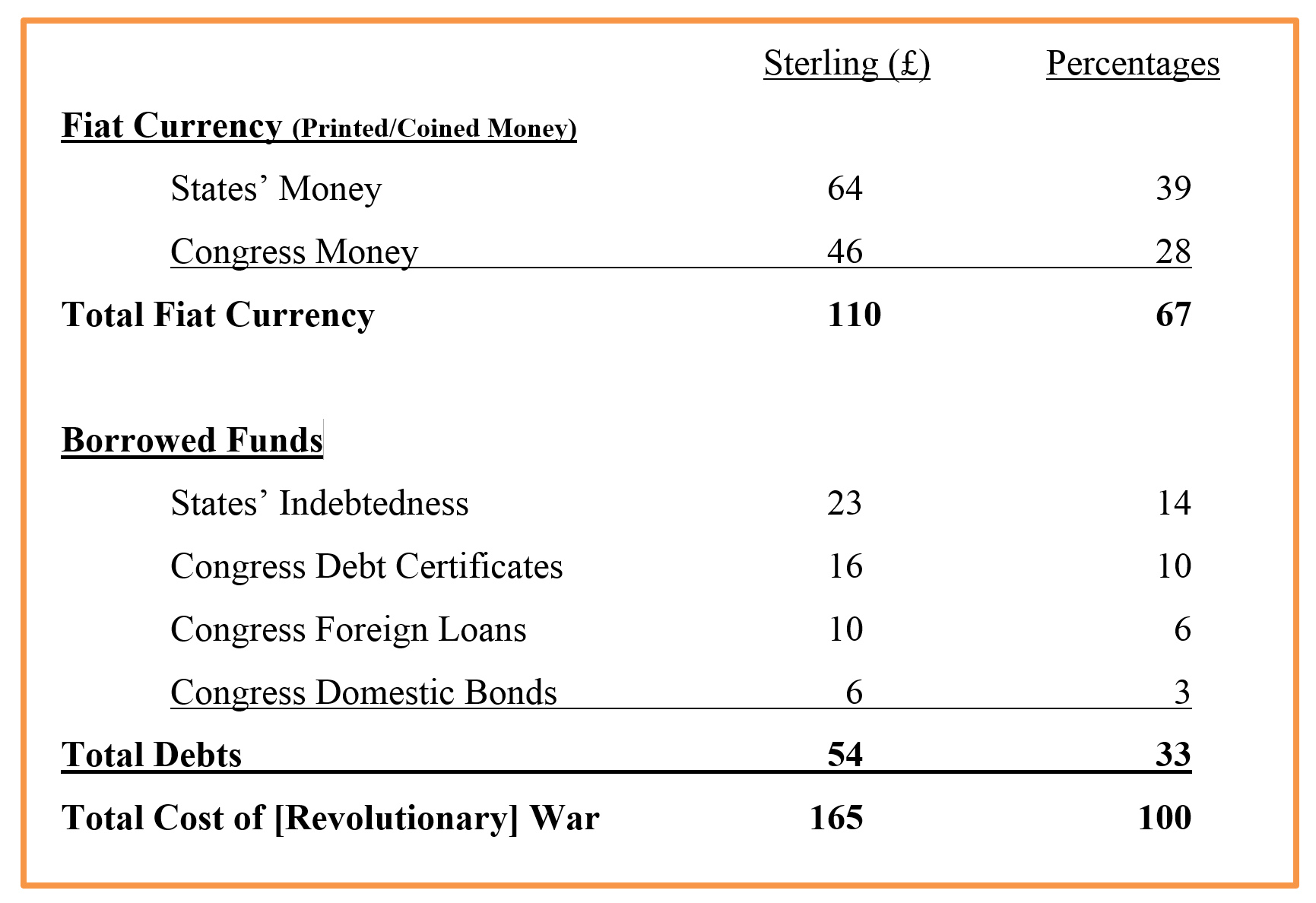

Estimated Funding Sources: War for Independence[1] (in millions of pounds sterling)

[infobox maintitle=”Glossary of terms to know for this article” subtitle=”

- Specie – any precious metal used as currency, like gold or silver

- Fiat Currency – any currency that’s valuable only because the issuing government says it is

- Face Value – the value of a currency that’s printed on the money itself” bg=”yellow” color=”black” opacity=”off” space=”30″ link=”no link”]

From 1775 to 1783, America used a variety of methods to pay for the war; some of which would seem very familiar to us even today. Here they are in order of percent contributed to the war effort:

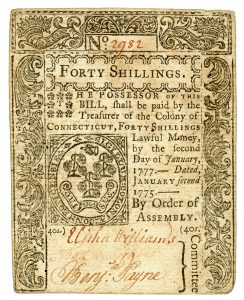

1 // The 13 States Printed Their Own Money (39%): We know that the thirteen colonies/states acted as individual sovereign countries in their time. That included the right to tax its citizens and to print money. So to pay for the food and supplies of its own militias, the states printed lots of money. But because taxes were such a hot button, for obvious reasons, the decision to tax residents to give value to the new currency was put off to sometime in the future (most states started in 1777). Some states also confiscated and sold Loyalist properties. But taxes also served as a mechanism to take currency out of circulation, therefore preventing inflation and keeping prices stable. That technique worked for a while until, as discussed below, the value of the federal Continental dollar started a tailspin and the confidence of all printed money started to drop.

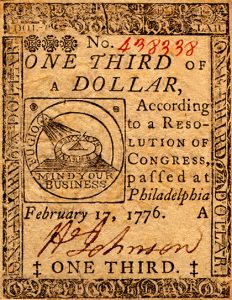

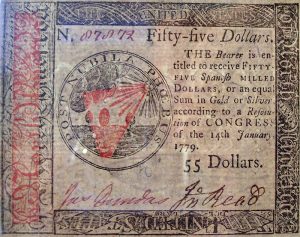

2 // Congress Printed Its Own Money (28%): Since Congress didn’t have the power to tax and there was no organized national bank, printing money was the primary source of funding Congress used during the Revolutionary War starting in 1775. And it printed a lot of money – the printing presses worked non-stop from 1775 to 1781! Lacking precious metals to mint coins, Congress printed paper notes that represented the equivalent value in specie. All types of weird denominations of a dollar were created, like “One Third of a Dollar” and so on. The two biggest problems with the so-called Continental dollars were that 1) there were so many printed and out there in circulation and 2) that they weren’t backed by specie (which is like gold or silver) even though the dollar’s face value said “This Bill entitles the Bearer to receive ONE Spanish milled DOLLAR or the value thereof in Gold or Silver…” But that wasn’t true at all. The dollars were actually backed by nothing and as the war dragged on, people figured that out, which is why the term “Not worth a Continental”[2] came into being. The never-shy Mercy Otis Warren called the dollars, “immense heaps of paper trash.”[3] The printed currency also carried such snazzy sayings as “Mind Your Business,” “Death to Counterfeiters,” and “A Lesson to arbitrary Kings, and wicked Ministers.” Each piece of currency was personally signed and numbered by an official to make them look more valuable and to discourage counterfeiters. But after a while, counterfeiting became a very serious problem with Continental dollars and, as a sabotage tactic, the British became pretty good at it. In fact, some eagle-eyed citizens got to the point where they could spot counterfeit dollars because they looked too good.

It turns out that as the war waged on, the confidence in the Continental dollar started dropping like a rock because they were so numerous and backed by nothing. After all, it is thought that in 1775 there was only $12 million in specie in the whole 13 colonies and none of it was in Congress’s hands. Since Congress printed $12 million in Continental dollars just getting the presses going and the ink flowing, you could see why a currency crisis was in the works. In all, during the Revolutionary War, Congress printed almost $242 million[4] in face value Continental currency. The true specie amount was about $46 million, as shown in the above chart.

3 // The 13 States Issued Their Own Debt Certificates (14%): Most of these were like state-issued war bonds. Also called “bills of credit,” they were “interest bearing certificates” with the buyer putting up their land as collateral. The patriotic buyer would then (or so they were told) get their principal back plus interest – assuming America won the war! As support for the common defense, states would also issue these as “requisition certificates” to vendors or suppliers to pay for food and supplies if the Continental Army happened to be camped in their state.

4 // Congress Issued Its Own Debt Certificates (10%): These certificates were also called (in politically correct verbiage of its time) “involuntary credit extensions” because they paid no interest and their value, tied to the Continental dollar, dropped like lead daily. These were mostly given out by the Continental Army quartermaster corps to citizens when buying or confiscating materials. In the last two years of the war, the Continental Army soldiers were also paid in these, so you can see why there was much grumbling – and mutiny. Some discharged soldiers sold their certificates to investors for literally pennies on the dollar.

5 // Congress Received Loans from Europe (6%): Before Saratoga, France had been smuggling small amounts of gunpowder and supplies to us through a dummy corporation. Although there was some bickering about whether these were loans or gifts, America tried to repay France in tobacco and IOUs. After the victory at Saratoga, from 1778 thru 1783, Ben Franklin and Silas Deane negotiated with France to give America six huge loans which just about broke the French Treasury. Following Yorktown, the world credit rating for England fell while the rating for America shot straight up. So in Amsterdam, John Adams easily raised $2.8 million for America at a favorable 5% interest rate (signifying low risk), and another $2.2 million from Dutch investors and the Spanish Crown. Some of the loans were used to keep the Continental Army intact in 1782-1783, but a lot of the money was spent in Europe to buy military supplies or to just make interest payments to keep America’s credit door open. With the signing of the peace treaty, even British investors wanted in on loaning America money!

Occasionally it’s brought up that the United States completely defaulted on its loans from France. That’s not entirely true. In 1785 the cash-strapped Congress halted interest payments to France and defaulted on scheduled payments due in 1787 because the states were forwarding so little money. But with the establishment of the Constitution and the order that it brought to American finances, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton was able to take action. “In 1795, the United States was finally able to settle its debts with the French Government with the help of James Swan, an American banker who privately assumed French debts at a slightly higher interest rate. Swan then resold these debts at a profit on domestic U.S. markets. The United States no longer owed money to foreign governments…”[5]

6 // Congress Sold Bonds to Wealthy, Patriotic Americans (3%): Similar to World War II savings bonds, these war bonds paid about 6% interest – again, assuming America won the war. Although some bonds were sold in Massachusetts, Connecticut and Pennsylvania (the possible site of the new government if America won the war), these bonds weren’t a huge success. For one, private loans paid more interest and if defaulted upon, could at least be recovered in an English court even if America lost. And two – well, a lot of the wealthiest Americans were Loyalists. The bonds were a bet that America would win the war. But if America lost, it was thought that just holding the bonds could indicate to the victorious British Crown that you supported the traitors. Not a good thing.

Downward Dollar Plunge and Near Bankruptcy

In tag team timing, from 1777 – 1780 Congress first took the lead in financing the war. By 1780, the states had their financial plans working well enough that they took the lead from 1780 – 1783 while Congress completely reorganized its financial house. It needed to! In July 1777, a Continental dollar had already dropped two-thirds of its value. It stabilized a little with the French alliance, but then again started a downward spiral. By 1780, Congress revalued its dollar as officially only one-third of its 1775 value. But the new and improved dollar still plummeted to the point where, by 1781, it took 167 dollars to equal the previous one dollar.[6] So what did Congress do? They couldn’t tax, so they printed even more dollars to be able to buy an ever-shrinking amount of goods and services. Prices were skyrocketing with severe depreciation and hyperinflation happening everywhere. States were still demanding that taxes be paid. It was a crisis, which threatened the existence of the new republic.

By 1781 and in desperation, Congress put strong-willed financier and Congressman Robert Morris into the new office of Superintendent of Finance. Some of the first emergency actions Morris took were to devalue the dollar, and then he squeezed about $2 million in specie from the states. But in a very controversial move, he suspended pay to the Continental Army enlisted soldiers and officers. Instead, he decreed that the army be paid in debt certificates or land grants until the peace treaty was signed. In 1782, the new consolidated national debt was so enormous that Morris suggested Congress only pay the interest on the debt, saying (this may sound familiar in today’s world) “… leave posterity to pay the principle.”[7]

Morris is a much checkered personality in American history and because of his bad personal land speculations leaving him owing $3 million, he ironically spent 1798-1801 in debtor’s prison. But it should never be forgotten that more than once Morris used his own fortune or credit to keep the country afloat during its worst hours. “My personal Credit, which thank Heaven I have preserved through all the tempests of the War, has been substituted for that which the Country has lost… I am now striving to transfer that Credit to the Public.”[8]

Economic Aftermath of the Revolutionary War

America’s Revolutionary War was very expensive. Not only did it sap economic resources in the country, the depreciated currency acted (as wise Ben Franklin put it), “among the inhabitants of the States… as a gradual tax upon them.”[9] And this was to a people who had been used to a life of light taxation before hostilities broke out. In the “be careful what you wish for” department, two economic historians speculated, “… that Britain was probably a ‘victor’ in defeat, for, after independence, U.S. taxes rose precipitously. From 1792-1811, U.S. per capita tax rates were over 10 times higher than the imperial taxes levied by the British from 1765 to 1775.”[10] But we know it wasn’t about taxes alone. It was about liberty and rights. “The colonists paid a high price for their freedom.”[11]

The predictable recession broke out following the Revolutionary War, with data showing the “period of contraction” (a.k.a. recession) running consecutively from 1782-1789.[12] Indeed, for a point of reference we all can relate to, financial history professors McCusker & Menard point out that during the Great Depression (between 1929-1933), per capita GNP fell by 48 percent. It’s estimated that those same economic markers (between 1775-1790) fell by 46 percent.[13]

The British war cost added a new national debt of £250 million onto their huge debt left from the French and Indian War of £135 million. The new debt carried an annual interest payment of £9.5 million alone. The loss of the war brought down the Lord North government within the halls of Parliament.

The Spanish war costs were pretty marginal reflecting their cursory involvement in the whole thing. It totaled to about 700 million reales, which Spain covered by taxing their colonies and issuing royal bonds.

The French war cost equaled over 1.3 billion livres in loans and supplies to America, plus the huge extra expenses to equip and send the French army and navy to America, and to attack British outposts around the world. Added to the 3.3 billion livres France owed from the French and Indian War, the resulting economic chaos eventually led to the French Revolution, which brought down the heads (literally) of the monarchy and nobility.

The American war costs, as shown in the above table, totaled approximately £165 million in 1783 values. It’s always tricky to convert 200 year old currencies gathered using imprecise war records – but that amount could roughly add up to about $21.6 billion in 2010 dollars.[14]

In America, the chaos of funding the American Revolution glaringly showed the weaknesses in the Articles of Confederation and a weak central government. George Washington had known all too well the many times in war he had begged for any money or supplies from a helpless Congress or indifferent states.

The establishment of the Constitution in 1787 brought fiscal stability to America, which was near collapse just after it had earned and paid for its liberty. It brought order to the national finances. It created a common market, common currency, it regulated trade and commerce, consolidated and funded the national debt, established a national bank, and gave Congress the authority to tax.

Okay, so maybe “gave Congress the authority to tax” wasn’t such a good idea.

Thanks to the office of the Historian of the U.S. Department of State and its Special Assistance group for supplying valuable source material regarding the American payment of foreign loans during the post-war period.

[1] The table has been produced based upon “Ferguson’s estimate of the total cost of the war”: Edwin J. Perkins, American Public Finance and Financial Services, 1700-1815 (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1994), 103, Table 5.4. Economic historians will recognize the invaluable research and work of two individuals in particular that this article draws from: Merrill Jensen, and especially his graduate student E. James Ferguson, who in the 1950s and 1960s, developed, tested, and published much of the statistical work that is still used today in the study of the Founding Era finances. Edwin J. Perkins is another good authority.

[2] Proceedings of the Twenty-First Continental Congress of the Daughters of the American Revolution, 21 (1912), 799.

[3] Mercy Otis Warren, History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution interspersed with Biographical, Political and Moral Observations, II; Lester H. Cohen, ed., (Indianapolis, IN: LibertyClassics, 1988), 287.

[4] To be exact – Congress issued $241,552,780 in face value Continental currency during the Revolutionary War. Eric P. Newman, The Early Paper Money of America. 3rd edition (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 1990); 16. E. James Ferguson puts this face value total at $227.8 million which includes the 1780-81 new emissions, saying “The actual sum in circulation may never be known” E. J. Ferguson, The Power of the Purse: A History of American Public Finance 1776-1790 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 43. Counterfeited currency was also in circulation.

[5] U.S. Department of State – Office of the Historian; Milestones: 1784–1800, “U.S. Debt and Foreign Loans, 1775–1795”, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/loans; (accessed January 12, 2014).

[6] Jack P. Greene and J.R. Pole, eds., The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1994), 364, Table 1. Taken from E. J. Ferguson, The Power of the Purse: A History of American Public Finance 1776-1790 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 32.

[7] C.P. Nettles, The Emergence of a National Economy 1775-1815, (New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1962), 33. In Jack P. Greene and J.R. Pole, eds., The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, 370. Morris spells “principal” as “principle”.

[8] Robert Morris to Benjamin Harrison, 15 January 1782, in The Papers of Robert Morris, 1781-1784, E. J. Ferguson, ed. In Charles Rappleye, Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution, (New York: Simon & Shuster, 2010), 259.

[9] Jared Sparks, ed., The Works of Benjamin Franklin…with Notes of a Life of the Author, II, (Boston, MA: 1836-1840), 424. From John J. McCusker & Russell R. Menard, The Economy of British America 1607-1789, (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 373.

[10] Lance Davis and Robert Huttenback, quoted in Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, Second Edition, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 208.

[11] McCusker & Menard, The Economy of British America 1607-1789, 374.

[12] McCusker & Menard, The Economy of British America 1607-1789, 63, Table 3.4.

[13] McCusker & Menard, The Economy of British America 1607-1789, 373-374.

[14] This computation converting from 1783 sterling pounds (£) to 2010 dollars ($) was done converting “real value” over time. The generally-accepted Web site used was MeasuringWorth.com http://www.measuringworth.com/ (accessed January 12, 2014). Edwin J. Perkins in The Economy of Colonial America (Appendix) computed $14.9 billion in 1985 real value dollars.

41 Comments

John,

Great job in describing a terribly complicated subject. There were so many moving parts to financing the war that it is very difficult to wrap one’s mind around it.

I would just add that there was an additional aspect to all of this that involved extracting valuable resources directly from towns to feed, clothe, and equip their soldiers. I know that in Massachusetts the stresses imposed on them was massive as the Provincial Congress assessed each town both specific numbers of men and amounts of goods (x number of shoes, y number of socks, z number of cattle and horses, pounds of beef, etc.). In an economy that heavily depended on country goods, it really beat them down heavily. Then, with all the ensuing economic problems persisting during the Confederation it all came crashing down with the so-called Shays’s Rebellion in 1786-87.

With regard to your reference to the counterfeiting going on, we have the British to thank for a lot of that, aided and abetted by Americans trying to profit from all the economic problems. The Brits put into place a massive operation to the continental currency and it had a significant impact. On the issue of alternative forms of currency, I am pasting below parts from my first book that dealt with the Shays time period:

By the 1775 to 1781 time period, there was a bewildering array of various types of money in circulation: gold and silver coins (quickly disappearing from usage), copper coins, colonial notes, counterfeit colonial notes, continental notes, secret issues of continental notes, counterfeit continental notes, continental four percent loan certificates, quartermasters’ certificates, registers’ certificates, loan-office certificates, lottery tickets, notes from private banks, Tory notes, private bills of exchange, private issues (“tokens” or “shin-plasters”), and “country pay.” A refusal to recognize those varying currencies, or to condition acceptance by paying a reduced amount to the presenter, opened a person to a charge of being “an enemy of his country.”

It became so bad in New York that in November 1776 one paper printed an advertisement, “Wanted – by a gentleman full of curiosities, who is shortly going to England, a parcel of Congress notes with which he intends to paper some rooms. Those who wish to make something of their stock in that commodity, shall, if they are clean and fit for the purpose, receive at the rate of one guinea per thousand for all they can bring….”

Again, great job in making sense of a complicated topic!

Thank you for your comments, Gary. And you’re right – counterfeiting, along with your phrase, “a bewildering array of various types of money in circulation”, combined with bartering makes it so hard to pin down real economic numbers for this time period. Thank you again.

Do you have any information or reference that identify the names or entities of the Dutch and Amesterdam lenders?

American success in the Revolutionary War is often presented in terms of the dedication and determination of soldiers and military leaders. The fact that this financing could be effected so quickly a sustain the war effort in spite of being so financially tenuous is a testament to just how acclimated the colonists were to some measure of self rule, and that a majority, even if not an overwhelming majority, either supported or at least accepted becoming independent from Great Britain. Without a reasonable amount of support from the population, this financing structure could not have worked at all, given the inability of the colonial governments to earn significant amounts of money from exporting goods.

Don,

That’s an interesting thought. However, in my research on Pennsylvania’s government during the war (a limited frame of reference, admittedly), they just overtaxed those who did not support the war to the point of bankrupting them. And in 1778-1779, they just confiscated the land and sold it at auction (and all the goods therein) to help fund the war costs for their state.

Additionally, it is hard to gauge the amount of people who strongly supported the cause of self-governance. While it certainly was popular, one has to wonder how many paid the tax to avoid being bothered by local authorities; keeping in mind that if anyone spoke ill or defamed the local committees, they could be thrown in jail and fined for the costs of their court proceedings (as happened often). It is hard to deny your tax collector when your neighbors are holding a gun in your direction.

Tom

Sorry, meant to include some actual evidence; PA Archives Ser 3 Vol 6, for example, lists all the excise fines for drafted militia not showing up for duty. Cumberland County, for example, fined one battalion (just one of many) some £7,000! Some men were charged a £100 fine for not reporting for duty. Every county charged about the same under the militia law ordinances. When one factors in countless additional fines and taxes, many worse than this, it is easy to see how they were able to meet certain war needs–especially later on in the war.

Excuse the bald-faced hucksterism, but I did an earlier article on what was happening in Groton, Mass. in 1781 when my uncle (who was a town selectman at the time and a former tax-collecting constable) led three riots in town opposing the collection of taxes which were expected to be paid in specie. He went on to lead the rebellion, but was cut down by government troops and which allowed Daniel Shays to step in: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/05/the-groton-riots-of-1781/

Gary,

I am writing an article on the draft riots in PA following the institution of the militia laws, because I think it is important to recognize that many American colonists did not support or condone what was happening in the country. Thanks for sharing the link.

I guess these protesters would constitute that 1/3 part of the population that Adams described as just wanting to get on with their lives and not be bothered.

It was an eyeopener to me to see this discord in the countryside and even more so when you consider the way that the coast-based Massachusetts authorities pursued those who were supposed to be their followers. That being said, in reading many of the Groton town meeting minutes of these years, I got the impression that the local authorities cut the residents some slack when they could not come up with the required requisitions. In fact, they forwarded letters to Boston seeking their understanding on the hardships they were causing.

So, from what I was reading, I see several levels of concerns playing off of one another ranging from not only physical locales, but economic and political class (read: elites) of those pursuing the taxes/requisitions, their myopic view of the effects it was having, and their inability (“refusal”?) to empathize – all of which was taking place in an environment virtually devoid of a court system that cared for the common man. It was a stacked deck all the way around.

Question: are we seeing the nascent fruits of independence as previously accepted concepts of class are being forced to give way to the demands of the populace, now possessed of a voice, of sorts? Do the haves really want to give way to the have-nots? Probably not!

So, by 1786, there was such a significant disconnect between the two camps that Shays Rebellion (that storm in the atmosphere that Jefferson talked about) just had to take place.

Just a reminder, Gary, that Adams’ famous passage about 1/3 of the population didn’t refer to the American Revolution; it’s been taken out of context for decades. See our discussion here:

https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/02/john-adamss-rule-of-thirds/

Oh Don, I was relying on that unspoken 1/3 hidden within the 2/3 that Adams was referring to in the 1813 letter to McKean! 🙂

I thought it prudent to share with you this letter from John Lesher, of Lancaster, dated 9 Jan 1778:

“Gentlemen,

I conceive it to be my Duty to acquaint you that I conceive I am no more master of any individual think I possess; for, besides the damages I have heretofore Sustained by a number of Troops & Continental Waggons, in taking from me 8 Ton of Hay, desroy’d Appics sufficient for 10 hhds [hog heads] Cyder, Eating up my Pasture, Burning my Fences, &c., and 2 Beeves I was oblig’d to buy at 1s. per lb., to answer their immediate want of Provisions, and at Several other times Since I have Supply’d detachments from the Army with Provisions. There has lately been taken from me 14 Head of Cattle & 4 Swine, the Cattle at a very low Estimate, to my infinite Damage, as they were all the Beef I had for my workmen for carrying on my Ironworks; I had rather deliver’d the Beef and reserv’d the Hides, Tallow, &c., but no Arguments will prevail, all must be deliver’d to a Number of Armed men at the point of the Bayonet. As my Family, which I am necessitated to maintain, consists of near 30 Persons, not reckoning Colliers, Wood Cutters and other day Labourers, my Provisions & Furnace, which I am about carrying on must of consequence be dropt, which will be a loss to the Public as well as myself, as there is so great a Call for Iron at Present for publick Use, & some Forges and Furnaces must of necessity fail for want of Wood and Ore.

“Gentlemen: The Case in this neighbourhood is truly alarming, when the strongest Exertions of Ecconomy & Frugality ought to be Practised by all Ranks of Men, thereby the better to enable us to repel the Designs of a daring Enemy, who are now in our Land. It strikes me with Horror to see a number of our own Officers & Soldiers, wantonly waste & destroy the good Peoples Properties; by such conduct they Destroy the Cause they seek to maintain. Instead of Judicious men appointed in every Township, or as the Case may require, to Proportion the Demands equal according to the Circumstances of every Farmer & the general benefit of the whole, these men, under the Shadow of the Bayonet & the appellation Tory, act as they Please, our Wheat, Rye, Oats & Hay taken away at discretion and Shamefully wasted, and our Cattle destroy’d. I know some Farmers who have not a Bushel of Oats left for See, nor Beef sufficient for their own Consumption, while some others lose nothing, as a man who has 100 head of Cattle lost not one; such Proceedings I think to be very Partial. Many Farmers are so much discourag’d by such Conduct, that I have heard several say they would neither Plow nor Sow if this takes place; the consequence may be easily forseen, unless some Speedy & Effectual method be taken to put a stop to such irregular Proceedings, and encouragement & Protection extended to the good People of this Commonwealth. I Shudder at the Consequence.”

Think=thing in the second line. See = Seed (8 lines from the bottom). That is what I get for typing it out over my lunch break. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Tom,

Those are great quotes and they add a lot in gaining an understanding of the incredible challenges the common farmer was facing as he watched his livestock and means of living taken away. That is not to say that the army was wrong in doing it as it has to get its resources from someplace to do its work, but it does reveal a split in who was doing the suffering, the lowly farmer or the farmer of means with connections.

Clearly, the hardships were not being evenly spread across the population. As in so many things in life, it is not what you know, but who you know.

Thank you, Don. When debates happen about what level of support (i.e. percentage of population) the revolution had in British America, your point: “Without a reasonable amount of support from the population, this financing structure could not have worked at all” is an important additional factor to help weight the Whig side of the rebellion equation. Good point and thank you for adding this!

Thanks for a highly informative article. I’m curious as to whether, with all the currency speculation and insecurity in the buying power of the Continental money, other economic means to pay for goods and services develop? In particular, was there a black market for goods or a barter systrem? What did the common man’s economy look like? Not necessarily looking for a detailed response but perhaps some recommended books/articles would be appreciated.

Steven – bartering was a primary form of commerce in colonial America making up the great term you used, “a common man’s market”. Bartering along with a much lesser amount of smuggling in a black market (within a more wealthy class of people) also helped to make up a wildly-varied economic system.

In terms of any books you’d asked for re. a “a common man’s market” examination, you can’t beat T. H. Breen’s “The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence”.

There are also sections in three books I used for this article which all touch on “a common man’s market”: Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, Second Edition / John J. McCusker & Russell R. Menard “The Economy of British America 1607-1789 / Edwin J. Perkins “American Public Finance and Financial Services 1700-1815. Thank you again for your interest!

Thanks, John. They’re now on my list.

Glad to pass the word on the books along, Steven! Thank you again for your interest.

Great job, John. This is a very fine article here. I enjoyed it. Not so incidentally, the financial and economical problems were, as you hinted at, solved by taxing Loyalists and disaffected citizens. In Pennsylvania, those apathetic to the war often were the primary victims of it, having their property impressed and suffering from insanely high taxation.

I have often wondered whether the Sons of Liberty had any inclination of the amount of taxes that their fellow citizens would have to front if a war began while they protested the Stamp Act. It’s certainly one of those interesting ironies.

Likewise, Vermont funded its military and state government with proceeds from sales sequestered (confiscated) Loyalist land holdings.

Gene,

I think that at a certain point this became common practice in most (if not all) of the colonies. Given the difficulties of 1778-1780, economically, it shouldn’t be surprising. It is something most people do not know about.

Tom – you’re right. It might be one of those ironies where the single focus at a time period is to WIN A WAR. And then IF the Americans won, would the confederation of states be able to govern and tax 13 very different states? I’m reminded of the times the United States has entered into a war in a region and after winning… have no clue of what to do next?

To echo John, the American leadership was not unaware of the contradictions in some of their actions. Right or wrong, their objective was to win the war. Consider the following letter excerpts:

“I am perfectly of your opinion, that the only object of importance at present, is the Defence of the Country. Until that is effectually secured, Leagues, Confederacies, and Constitutions are premature, except as temporary expedients. I wish that sentiment prevailed more generally, and that it was not already too confidently believed by those, at a distance from the scene of action, that every thing was done, and that we should every one live quietly under his own Vine and Fig-tree.”

– Samuel Johnston (President of the North Carolina Provincial Congress, 1775-1776) to Thomas Burke (Delgate from North Carolina to the Continental Congress), 19 April 1777

“I sent an order for the Charlestown artillery to march to Purisburgh; but Gen. Bull informs me, they will not stay longer than the first of March. I fear our militia law will ruin our country. [I]n contending too much for the liberties of the people, you will enslave them at last; remember, my friend, it has always been the maxim of all communities, to abridge the people of some of those liberties for a time, the better to secure the whole to them in future.”

– Brigadier General William Moultrie to Charles Pinckney (President of the South Carolina Senate), 11 February 1779

Also, at least in SC, the fine or tax that exempted someone from militia service was not a law passed by the revolutionary government, but one that had been on the books since 1747, and that the new government continued (as they did many other provincial laws). By 1777-78, however, the Whigs had become more stringent about not only requiring inhabitants sign an oath, but that they provide active participation as well. So while the fine/tax was still a legal option, the Whigs went out of their way to make it clear that it really wasn’t an option.

John, thanks for an interesting article. I would, however, suggest a bit more clarity in discussing financial assistance in the form of vital military supplies provided by France, and to a lesser degree Spain, before the formal alliance. These supplies, especially gun powder and weapons, provided through Hortalez and Company were valued at millions of livres and little of this covert aid was ever repaid. Robert Morris was tasked with obtaining agricultural goods from the various colonies to ship to Europe to sell to pay for these supplies. However, as in his other efforts to get funds from colonial governments, this proved quite difficult.

Of course, starting with World War I, American has repaid this debt with interest in both blood and treasure.

Thank you, Ken. And you’re correct about covert foreign aid before Saratoga. Because of word restraints in article submissions and not wanting to stray too far off the primary focus, the best I could do to touch on the subject you raised was to say, “Before Saratoga, France had been smuggling small amounts of gunpowder and supplies to us through a dummy corporation. Although there was some bickering about whether these were loans or gifts, America tried to repay France in tobacco and IOUs.” The entire case you bring up would be very interesting, I feel, to readers and worthy of an article by itself. Thank you again.

Thank you John for writing this excellent article. It peaked my interest as I am an accountant/auditor and not really reading up on this topic of the American Revolution, I knew next to nothing about it. I know how tough it is to write an article talking about currency, the economy, loans, debt, the buying and selling of loans, the different currencies used, what actually “backed” the printed monies, etc., you did a great job of informing and keeping the readers attention.

I will get copies of the four books you mentioned in the comment above, thanks for providing them. Do you recommend a book about Robert Morris? I always have heard people refer to him at the “financer of the revolution.”

Brian Mack

Fort Plain Museum

Thank you for your kind words, Brian, and yes – the four books I mentioned to Steven are all available through Amazon Books, maybe your local new or used book store, or possibly the publishers. It’s funny that you mentioned an additional book (on Morris) that I also own and used for this article, but to a much lesser extent as you can gather.

It’s the 2010 rather-epic bio of Morris by Charles Rappleye: “Robert Morris – Financier of the American Revolution”. At 600 pages, it pretty well chronicles the life and times of Morris, and shows the complex character that he was. Since he came into the national economic picture quite a bit later in the story, the other four books give you a birds-eye snapshot of the whole situation before, during, and after the Revolutionary War. Any of them or all five books would make up quite a specialized library of the subject! Thank you again.

A most interesting discussion triggered by John’s truly important article – but we are barely scratching the surface. Consider Gary Shattuck’s article on the “Groton riots” he referred to in the discussion – this sort of thing was happening absolutely everywhere in some form or another. Paying for the war, both during and after the fighting, heightened local antagonisms on the micro level; in aggregate, these internal struggles made the young nation ungovernable. We cannot even begin to understand the politics that culminated in the Constitution unless we look hard at the struggles over taxation to pay for war debts of every sort. Consider this: in a six month period shortly before the Federal Convention of 1787 (what we now call the Constitutional Convention), from October 1786 through March 1787, the states turned over a grand total of $663 to the federal treasury to keep the Confederacy afloat. To use a modern idiom, the federal government, such as it was, had been shrunk to the size where it could drown in a bathtub. People like Madison saw the handwriting on the wall. Unless the system of public finance was radically altered, “the United States, in Congress assembled” would go under. In April 1787, when Madison compiled a memorandum listing the “Vices of the Political System of the United States,” his first item addressed the heart of the problem: “1. Failure of the States to comply with the Constitutional requisition.” He elaborated: “This evil has been so fully experienced both during the war and since the peace, results so naturally from the number and independent authority of the States, and has been so uniformly exemplified in every similar Confederacy, that it may be considered … fatal to the object of the present system.” Figuring out a workable system of federal taxation was first and foremost on the framers’ minds. We don’t like to hear it, but to taxes we owe our Constitution – and it all started with the need to pay the war debts John lays out.

So very true. It also explains our relentless pursuit of international trade while seeking to gain some semblance of credibility with foreign powers (a contest lasting until 1815). Finances, to include those involving self interest, in one form or another from the Stamp Act to Jay’s Treaty to the Embargo were continually at the heart of the matter. That must always be recalled whenever we use terms such as “freedom” and “independence,’ remembering to do so in the context of those times, not now as so many seem to want to cling to.

Ray – well said and well-framed, as one might expect from you! Yes, the ultimate irony is that “… to taxes we owe our Constitution.” Thank you for your big picture summation.

John, I certainly do appreciate and respect the amount of research and analysis that went into your article, as readily demonstrated by the numerous comments/reactions. My focus, as you probably recognize, is on the intelligence aspects of the period and the covert aid program by the French is a rather comprehensive chapter in my book. Thus repeating it in the Journal would take space away from other original articles. The only general point I would hope to make is that French aid, in the 1776-78 period, was vital to maintaining the army in a combat capacity. And, if we are to learn history’s lessons, perhaps we should not be as surprised or upset when other organizations/states we support “covertly” do not replay our costs.

Ken – there’s that ancient axiom that it’s always a different story when it’s your own money that’s not being repaid! (Plus I made a note that I need to pick up your book to read). Thanks again.

British forces were often cut off from supply bases. For example, Cornwalis stayed in North Carolina after Guildford Courthouse partly because he despaired of marching back south without supplies. How did the Patriots prevent the British from just buying supplies from local farmers and businessmen? British sterling would have been very attractive to sellers whose alternative was Patriot script.

Fascinating article. Really breaks it down in a way I can understand.

Can I ask though – what happened once the debt was assumed? The Federal government bought the debt from the creditors by issuing them Bonds, correct? And these creditors accepted that the Federal government would make good on those Bonds. But how did the Federal government then pay back the Bonds? I mean, it’s all well and good for me as a creditor to know I’ll get paid back, but there’s certain people who were owed money and needed it immediately – soldiers and farmers, who couldn’t simply eat the paper.

I assume it was not Bonds alone which helped finance the debt, but the issuing of Notes from the newly founded First Bank of America, correct? And the people issued these Notes as payment from the government could trade those on for material objects owing to confidence in the bank (over-subscribed on the first day!).

Also, those Debts/Bonds would still need to be paid eventually, so how was that done? Was this done in gold from the (1) US Mint, or (2) Notes from the Bank, or (3) from Taxes?

And (2) if done in Notes from the Bank, do you happen to know whether they inflated the supply of Notes in order to do so? I mean, the Bank was only allowed to have $10million loaned out at any one time – much smaller than the domestic debt – and I assume this cap included the amount of promissory notes it could be putting into circulation too?

Or if (1) done in simple Gold from the Mint, where was it getting the gold to Mint all this currency? Surely that has to be paid for somehow also?

Did it simply come down to (3) Taxes, ultimately? Taxes to place value in the Bank, Taxes to buy Gold for the Mint, and Taxes to simply pay Creditors?

This article won’t answer all of your questions, Rory, but it might provide some insight on some of them: https://allthingsliberty.com/2016/08/bond-prices-tell-us-early-republic/

Thank you, Don.

I would like to note of a foreign contribution that more accurately attributes to the naming of American currency made by King Juan Carlos of Spain to George Washington. Through DeGrasse-Sangronis Convention through the authority of Admiral Bernardo Galvez governing of the lower Mississippi Delta settlements and controlling the river’s entry by the British navy. Historical records indicate 500,000 llbs. of gold and “8 Reales” Silver dolár were donated and loaded on 38 French ships in Havana Harbor in August 1781 for the Battle of Yorktown and Battle for the Chesapeake. If you look at the tail of the * Reales coin you can vividly see the two columns and the silk wreaths around them as the first recognition of the $ dollar sign. According to Spanish accounting manifests for bounty and cargo on ship manifest of its time between Havana and in the Old world clearly are commonplace. It is more likely that continental infantry is likely to only fight if paid in the Silver Dolár as a world currency for it was not likely to be counterfeited as it was minted in Spanish Mints in Secure forts Peru and Mexico a century before Britsh colonies arrived in Jamestown. Galvez statue sites on the North Entrance of US Department of State today. Google Cuban Contribution to Yorktown and Bernardo Galvez plea for payment of debts incurred by Patrick Henry in Cuba.

I dare say that the vast majority of people in the united States just assume that the spoils go to the victor and have no idea that all this money was owed to so many different places. Can anyone tell me whether these debts were all paid off, especially in regard to Britain, France, Spain and Holland. There are some who say that those debts have never been repaid and foreign banks have a strangle hold on the States even today. They maintain that those loans from foreign banks were the real reason for the civil war, the great depression even the problems of 2001 (70 year loans coming due). Any help on this would be greatly appreciated.

The debt to Spain was never repaid, and has been estimated based on today’s currency value to be approximately three billions dollars.

Thanks for a very interesting article. It is not common to find an US historian acknowledging foreign assistance for the Revolution. As Hamilton said: “If we are to be saved, France and Spain must save us.”

By the way the equivalence of lives tournoises and Spanish reales is a tricky matter. 1 real is 5 lives, thus the Spanish costs were, according to your article, actually 3.5 million livres. But, unfortunately you do not consider the cost of waging the war in Europe (Gibraltar and Minorca) the campaign of the combined fleets at sea, and the costs of sending 11.000 soldiers plus a fleet of 80 ships to fight in the gulf coast and the floridas under Galvez. A lot of money was used too to pay for the french fleet of De Grasse operating between 1781 and 1782. The costs of the war against England for Spain was huge.