It seems that almost every author who mentions British soldiers in their discussion of the American Revolution includes adjectives like “young” and “inexperienced” without any basis for those descriptors. They apparently take for granted that soldiers were young, and soldiers sent to fight in America were inexperienced. Neither of these generalities is true. Sure, there were some young men and some inexperienced men in the British ranks, but they were not the majority. Let’s look at some data gleaned from British muster rolls, pension records and other sources to get a better picture of age and experience demographics of the redcoats who served in America.

When the war began, there were several thousand British soldiers already stationed in America. If we take a sampling of those who marched out of Boston towards Concord on 19 April 1775, we find that they had quite a bit of military experience. They were Grenadiers and Light Infantry – two companies from each regiment in Boston, composed of men selected for their experience and ability. The muster rolls of one regiment, the 23rd Regiment of Foot (which had the title Royal Welch Fusiliers) give the soldiers’ names in that regiment’s Grenadier and Light Infantry companies in early 1775, and we can trace the names backwards through the rolls to find out how long each man had been in the regiment.[1] The results are revealing:

|

Military Service of two Companies of the 23rd Regiment, 19 April 1775 |

||

|

Years of service Advertisement |

Grenadier Company |

Light Infantry Company |

|

1 to 5 years |

10 |

7 |

|

6 to 10 years |

16 |

23 |

|

11 or more years |

13 |

10 |

Some British officers who were on the expedition to Concord complained that their men lacked discipline, sometimes firing without orders and rushing too impetuously towards the enemy. Many writers interpret this as a lack of military experience, when it more likely shows a lack of combat experience. Probably only a few of these men had been in battle before, but they certainly knew basic military procedures after years in the army.

This example is a little unfair, because it shows Grenadiers and Light Infantry – soldiers carefully selected for their experience. For a better look at the army in general, let’s turn to another regiment, the 22nd Regiment of Foot. This is a good choice because there was nothing special about the way this regiment recruited, where it had served recently, or anything else to make it highly distinctive. Every regiment was a unique assemblage of men, but the 22nd provides a pretty good example of most British regiments that served in the American Revolution. The 22nd arrived in Boston in late June 1775, shortly after the battle of Bunker Hill. They had been in Ireland for the previous two years, and in Scotland for a few years before that. They had been brought up to full strength before embarking for America, partially by recruiting and partially by taking in men transferred from other regiments. When this newly-deployed regiment disembarked in Boston, it included 416 sergeants, corporals, drummers, fifers and private soldiers. Here’s how long they’d been in the army:[2]

|

Military Service of 416 Men of the 22nd Regiment, 1775 |

|

|

1 year or less |

41 |

|

2 to 5 years |

128 |

|

6 to 10 years |

167 |

|

11 to 20 years |

36 |

|

More than 20 years |

14 |

|

Not known |

30 |

A similar study of any regiment in America early in the war would show similar amounts of military experience. Again, few of these men had wartime experience, but they certainly were well-versed in the basics of hygiene, weapons handling, maintenance of clothing and equipment, marching both in formation and for travel, and living in the field. They had a lot of adapting to do, but they didn’t lack basic martial knowledge.

With that amount of experience, how old were these men? We think of men joining the army in their late teens, but detailed study of available data on the 22nd and other regiments reveals that most British soldiers enlisted later than that. Recruiters could take men at any age, preferring those who were at least seventeen, that is, close to fully grown. The majority, however, enlisted in their early twenties, often after having completed trade apprenticeships, meaning that even new soldiers were seldom young soldiers.[3]

Age information is more difficult to come by than experience information; to date, we’ve found the ages of just under half the 22nd Regiment’s men who landed in Boston:[4]

|

Ages of 183 Men of the 22nd Regiment, 1775 |

|

|

15 – 20 years old |

3 |

|

21 – 25 years old |

20 |

|

26 – 30 years old |

65 |

|

31 – 35 years old |

50 |

|

36 – 40 years old |

24 |

This may seem surprising, but again it is completely typical of British regiments that served in America.

Warfare tends to be hard on soldiers, so the demographics of a regiment changed during years of service in the American Revolution. Men died of wounds and illness, men were discharged due to age and infirmity, men deserted. New men arrived, either recruited or transferred from other regiments. Let’s look at the same regiment six years later, bearing in mind that the 22nd had been on several campaigns but had not suffered exceptionally, nor been sheltered in any unusual way; once again, it is a good typical example. From 1775 to 1781, almost 200 men had left the regiment by death, discharge, desertion or transfer, and almost 450 new men had arrived by recruitment or transfer.[5] The authorized full strength of the regiment had been increased substantially; there were now 670 men in the regiment. Although many were new, they weren’t all new to the army. Almost 100 were transferred from regiments that had been sent home, or were escaped prisoners of war who had rejoined the army (including, for example, many that had surrendered at Saratoga in October 1777). Among the recruits, most of whom had arrived in America in 1776, were many who had seen prior military service (including, for example 13 of the 40 German recruits who joined the regiment in 1776[6]). Even the 33 recruits who arrived in 1781 had mostly been enlisted at least a year before and had been in training ever since.[7]

We have not, at this time, determined the levels of experience for the regiment in 1781; the large number of new men with unknown backgrounds makes the task difficult. As for age, we know how old 262 out of 670 men were in 1781. Even though many men had left since 1775, and new men had arrived, the age distribution remained similar to what it had been when the regiment first landed in America:

|

Ages of 262 Men of the 22nd Regiment, 1781 |

|

|

15 – 20 years old |

3 |

|

21 – 25 years old |

28 |

|

26 – 30 years old |

30 |

|

31 – 35 years old |

83 |

|

36 – 40 years old |

65 |

|

41 – 45 years old |

33 |

|

46 – 50 years old |

17 |

|

51 – 60 years old |

4 |

|

> 60 years old |

1 |

All of this information pertains to one regiment, but it is echoed in data for almost every British regiment that served in America in the 1770s and 1780. The British army in the American Revolution were supplemented by German allies, loyalist regiments raised in America, and Indian allies, but its nucleus was composed of career soldiers. They were a diverse lot, but two things about them are clear: they were not young, and they were not inexperienced.

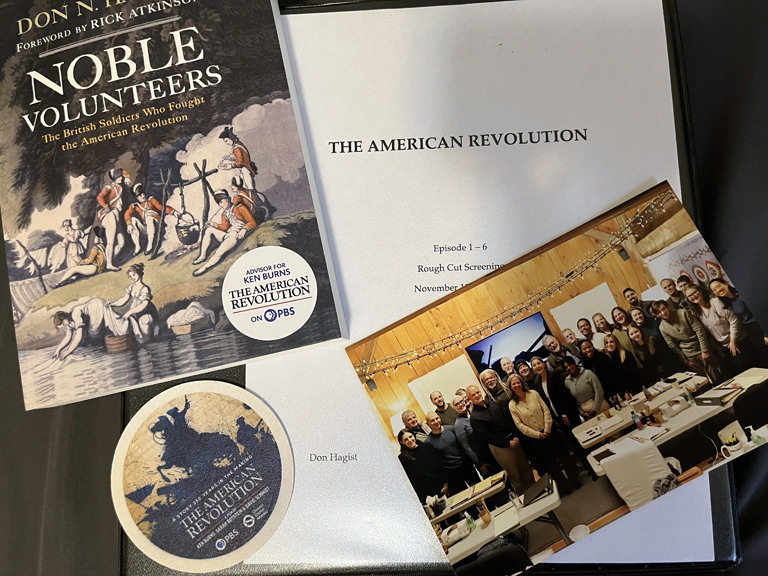

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Soldiers of the 25th Regiment of Foot in Minorca, circa 1771. If they don’t look young, they shouldn’t – they weren’t. Detail from painting by Cecil C. P. Lawson, Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, after original in the National Army Museum, Chelsea, England.]

[1] Muster Rolls, 23rd Regiment of Foot, WO 12/3959, /3960, British National Archives. The data presented here assumes that each man began his military service when he first appears on the rolls of the 23rd Regiment; in reality, men usually enlisted in recruiting parties months before appearing on the muster rolls, and some had prior military experience in other regiments.

[2] All data is from Muster Rolls, 22nd Regiment of Foot, WO 12/3871, /3872, British National Archives, supplemented by muster rolls from other regiments in cases where men transferred.

[3] For a detailed discussion of recruitment and training, see Don N. Hagist, British Soldiers, American War (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2012).

[4] Age data is compiled primarily from British army pension records, WO 116, WO 119, WO 120 and WO 121, British National Archives, supplemented by other available data for individual soldiers.

[5] Note that many individuals came and went during this period; for example, more than a third of the 63 recruits that arrived in 1779 died of illness within their first year in America. Muster Rolls, 22nd Regiment of Foot.

[6] Don N. Hagist, “Forty German Recruits: The Service of German Nationals in the 22nd Regiment of Foot, 1776-1783,” http://www.revwar75.com/library/hagist/FORTYGERMANRECRUITS.htm

[7] Hagist, British Soldiers, American War, 10-11.

19 Comments

Based on the social strata of 18th C British society I’m not surprised that the ages bulk in the 31 to 45 range. While writers may focus on the young and inexperienced notion, the army/navy was also considered the greatest in the world. So which is it? One would think the young/inexperience concept is embraced by those who want to minimize American military achievement while the greatest army is embraced by those holding out victory as “Almost a Miracle.” As service length suggests a better trained force it would appear that Don’s article would support the greatest army concept. This was probably true of all European armies who would also show similar metrics. the article also begs the question, what of the officer corps. Since commissions could be purchased as well as earned on a battlefield, could the officers be a younger grouping? Or, since being an officer was a career election, often by the sons who didn’t inherit the manor, would their grouping tend to be the same or older? Thanks, Don.

Your “almost a miracle” conclusion is accurate, Steven, at least where battlefield victories are concerned. Much emphasis is placed on the battles that Americans won – or at least held their own in – without much mention that those victories were few and far between. But winning a war takes much more than winning on the battlefield, as Americans today should be keenly aware. I think there’s a tendency to assume that, since Americans won the war, it must’ve been due to inferior performance of the British military, which is not necessarily the case.

I haven’t studied the officer corps, but there are some good studies available that will address your questions (watch for the upcoming review of Protecting the Empire’s Frontier: Officers of the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment of Foot during Its North American Service, 1767-1776 by Steven M. Baule (Ohio University Press, 2014)). British officers generally obtained commissions in their late teens, a bit younger than the average enlistment age for soldiers, but did indeed often serve for long careers. The subalterns (ensigns and lieutenants) were liable to be young (in their late teens and early twenties), but the captains, majors and lieutenant colonels were more likely to have ten or more years in the service – with the usual range of exceptions, of course.

Neat article, Don. You are at your best when discussing the common Brit soldier.

Also a neat picture to head the article. Lots of interesting detail–some guys looking at viewer (where’s the discipline?), a disdainful look on the closest rear ranker, earlier style tricorne? with point over left eye as it should be, gold regiment, bastion lace, belt around waist rather than over shoulder (latter later practice, isn’t it?), painted leggings rather than ankle spats, locks appear to have cock down with hammer closed on it. I notice a grenadier in line with a herd of hatmen. What’s the occasion? How common might this be? Is he functioning as the squad’s nco?

Great observations on this image, Mike.

This detail is from a copy of one of the famous “Minorca Paintings” attributed to Giuseppe Chiesa, depicting the 25th Regiment of Foot in the early 1770s. The originals are in the National Army Museum and are among the most widely studied images of British soldiers from this era because, although not large in size, they are rich in detail. This copy is a fair rendering but easily distinguished from the original. All of the nuances of head position are per the original. The hats in the original look more like the cocked hats we’d expect. These men appear to be standing in formation to receive orders for some routine duty – attentive but relaxed. Regimental orders routinely call for “a man from each company” or “fifty men from the regiment” or what have you, rather than assigning duties by companies. With this in mind, it is completely natural for grenadiers to be mixed in with battalion men.

During the American Revolution, grenadier and light infantry companies spent much of the war detached from their regiments in composite battalions – meaning that you’d be likely to see a formation like this one in Boston before hostilities broke out, but not while the war was in full swing.

My 6th Gr-Grandfather John Worthington was 57 years of age (born in 1723) when he was taken a Prisoner of War (1781) while in the British Legion under command of Lt. Col. Banastra Tarleton. Yes indeed there were old men especially those called back into service in the British Legion. One of my other Gr-Grandfathers was Benjamin Martin so I’m rather found of the fictionalized movie “the Patriot” even if the characters and events were fictionalized.

This is a great observation, Donald – the Loyalist troops raised for British service also had a very broad age demographic, just like the regulars, even though the loyalist regiments were raised only for service during the war.

It may interest you that your ancestor was not “called back into service.” Service in Loyalist regiments (and for the most part in regular British regiments) was strictly voluntary. Your ancestor didn’t serve because he was called, he served because he chose to!

Redcoats in North Carolina, say, while outnumbered by local Tories serving under them, must at times have been surprised at the youth of the Patriots. I keep seeing a scattering of 1832 pension applicants saying they volunteered at 14, 15,16, 17 years old. (Of course, the very youthful would have been the ones most likely to survive till 1832.) I assume the young Patriots would have faced young Tories as well as the older Redcoats–or not? Does anyone know how youthful the Tory soldiers were?

My ancestor was a Captain in the 5th Regiment of Foot, Francis Marsden was his name. He fell wounded at Bunker Hill aged 22 and died 5 years later. I understand before joining the 5th he was in the West Yorkshire Militia back at home so was a career soldier. He was the only son however. Seems rather young age for a Captain but the family had money then (and connections like as not).

22nd Regiment are “The Cheshire Regiment.” And still exist. One of the few never to have been amalgamated.

That was true, Ragnar, up until 2007. The 22nd (Cheshire) Regiment was the last county regiment to remain unamalgamated, and also the last to continue using its number. But the sweeping changes to British army organization proposed in 2004 and completed in 2007 saw the creation of the Mercian Regiment, with the former Cheshire Regiment as its 1st Battalion. The Mercian Regiment uses the buff color and oak leave badge of the Cheshire Regiment.

Thanks Don. I had heard rumours, but I never heard the final outcome.

Does anybody know what the painting of the redcoats in the article is from? I’d like a copy of that.

Soldiers of the 25th Regiment of Foot in Minorca, circa 1771. Detail from painting by Cecil C. P. Lawson, Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, after original in the National Army Museum, Chelsea, England.

You can see a digital image of the original painting on the National Army Museum’s web site (link).

If this link doesn’t work properly, go to the web site and select Collections, then search for 25th Regiment. You’ll find several of the paintings in this remarkable series.

Hi Don, I cited this article of yours in my forthcoming book “Igniting the American Revolution” (Chicago: Sourcebooks, 2015). http://amzn.to/1HCrpzg

Great article again, Derek

Great,Derek! Glad the information is useful!

I think what accounts for the “inexperience” of the British army of the 18th century, could be explained by our current understanding and orientation of modern military training, as well as in the difference of how we view military service today. (This among other factors.)

True British soldiers of the 18th century were certainly not inexperienced in their familiarity with their own military protocols. They also weren’t inexperienced in their contribution to society at large either. Many of them were tradesmen, who went in as tradesmen and came out as tradesmen. Nor were they inexperienced in their sense of belonging within their own group / support system / microcosm of society.

What seems strange to us today though, is that your average 18th century redcoat was not at all psychologically prepared via any sort of training to cope with combat. Matter of fact, your average colonial civilian was probably better prepared psychologically speaking, at “killing things / people” than your average British soldier. (Not a lot of wolves, bears, coyotes, rattlesnakes, or “hostile” natives etc left in Britain by 1750.)

Psychological preparation to deal with the stress of combat would not be formally addressed in training until after Word War II.

After World War II, the American army was trained quite differently than it had been in previous generations: (which I’m sure today rings true for most modern militaries). The change in training increased the potential “kill rate” of individual soldiers. (Kill rate being number of enemy combatants one soldier is mentally and physically prepared to take out.) Some of the increase in “kill rate” obviously has to do with changes in weapons technology. The other factor though is in how soldiers are now trained in how to fight a war. Today, more can be accomplished with fewer soldiers who are better equipped (both in terms of armaments and mentality) than in the past.

Most civilians who’ve never been in the military, are aware of the “effectiveness” of modern warfare (generally considering every war starting with World War I). Wars today are more costly, more deadly and generally involve bigger armies, more nations, more people (on account of the notion of “collateral damage” of (or purposeful attack / terror bombing) of civilian targets / national infrastructure.) than was common in the past. Most civilians know militaries today are “more effective”, but they don’t know why.

“Effectiveness” today is mostly accomplished by desensitizing soldiers to the death and destruction going on around them, hopefully long enough to get them through the war; only to address the huge psychological repercussions when they get back home. Of course this approach isn’t wholly successful, seeing how higher percents of military people returning from wars today suffer from chronic PTSD.

There are multiple sociological reasons for this. The nature of warfare has changed, the “rules of engagement” have changed, the locations of where wars are fought has changed (i.e much more urban combat – wasn’t much fighting in the streets of Philadelphia when the British army marched in), social supports that would have been available to soldiers in the past (families and community) have broken down, role of religion, morals, ethics and spirituality in post modern society has broken down, crime in both civilian and military communities has increased.

I did a research project once for one of my college papers on crime in the American Revolution. As it turns out, the data in this article sheds some light on what I’d found.

For example: No where in colonial British orderly books do we read that they had problems with soldiers being sexually assaulted either by other soldiers, NCO, or officers (as we have in our military today). Matter of fact, both armies in the American Revolution were amazingly well behaved. Petty theft of property belonging to others in the same army was the most common crime. Murder and sexual offenses, though rare, when they did occur, again the victims were usually people connected to that army. As per the regular British army, almost never did violent crimes committed by soldiers against civilians cross sides. The vast majority of “war crimes” that took place in the American Revolution were colonial civilians against other colonial civilians.

The Continental army had a higher petty theft rate than the British army and violent crime in the Continental army proper was only marginally higher than the British army. (Colonial militia crime rates, I didn’t have stats on.) Crime rate differences between Continental and British armies I think had to do with severity of punishment, as well as the fact that the British army was better supplied with material goods and support people (soldiers’ wives / families, Loyalist units and Loyalist refugees seeking employment / protection from the British army) than was the Continental army.

Consequently, I have concluded that the plethora of Loyalist refugees that pursued the British army, likely brought to that army a reasonable pool of potential wives for soldiers, which would have cut down on issues inherent with prostitutes. The Continental army had such a problem with venereal disease that George Washington stipulated that all soldiers were personally responsible for paying for their own treatment. The crown did not adopt that policy with the British army until the Napoleonic wars. We also know that the British army was reorganized after the American Revolution and soldiers who had North American wives (and children) and could not afford to pay passage for family back to England, were sent to Canada.

Now looking at this article here about “ages” and “years in service” of British soldiers adds some missing pieces to my hypothesis that the British army in the American Revolution did not have the same problems with prostitutes that the Continental army had. This makes sense seeing how the vast majority of British soldiers were older (and would be more likely looking to start families) than the vast majority of Continental soldiers. (Average age given for Continental soldiers is said to be 18.)

(Back from my “side track” to my original thought about military training.) Here is where our understanding of the point of military service today differs from the understanding in the 18th century and why we are probably more immune to the notion of conscription than would likely have been acceptable in the 18th century. More people today are apt to look at the “point” of military service is to fight wars; where as in the 18th century, I don’t think fighting wars was the focus. I know that seems strange to us because we generally think “what else do armies do other than fight wars”?

In past centuries though, it was not uncommon for standing armies (look at ancient Rome) to be used as police forces. The British army was originally sent to Boston back in 1770 because of riots. King George’s “calling up the troops” would have been the equivalent of “calling out the national guard” today. Now keeping that in mind, how do you think members of the national guard would react to a full scale war waged against them by occupants in American cities? You’d probably get something very similar to the reactions of the British soldiers in Lexington and Concord. Not only were they not prepared for combat, they certainly weren’t prepared for “Wait a minute, these people aren’t suppose to be trying to kill us!”

A question for the author of the article: how likely is it that a Sergeant in the British Army could retire in say the year 1780 at the age of about 55 ?, having been promoted through the ranks. Thanks.

Not just likely, but typical. Most British soldiers of this era enlisted in their early twenties – some much younger, some much older, but the vast majority in the early twenties. In most cases, they served until they were no longer fit for the long marches and rudimentary living conditions of campaigning, after which they were discharged; careers of twenty or thirty years in the infantry were common. Men who were appointed corporal, then serjeant (to use the period spelling) were likely to have long careers if their health allowed it. So if we look only at discharged serjeants during the 1770s and 1780s, we see that an age range of 40 to 60 was typical. A man discharged at that age was eligible to receive a pension, but had to appear in person before an examining board in Chelsea, near London, to do so.

A note on the terminology: non-commissioned officers were “appointed”, not “promoted”; and old soldiers “took their discharge” rather than “retired.” Commissioned officers did get “promoted” and “retired.”

You’ll find many stories of soldiers with long careers on my blog, http://redcoat76.blogspot.com