The biggest myth of Paul Revere’s ride may not be that Revere watched for the lantern signal from the North Church spire, as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem described. Nor that he was a lone rider carrying Dr. Joseph Warren’s warning all the way from Boston to Concord. Nor even that Revere yelled, “The British are coming!”

Instead, the biggest myth might be that Paul Revere’s ride was crucial to how the Battle of Lexington and Concord of 19 April 1775 turned out. Rural Massachusetts Patriots were already on alert, especially after they spotted British officers riding west through their towns. Other riders were spreading the same news. Hours passed between the first alarms and when the opposing forces actually engaged, giving Patriots time—more than enough time in some cases—to assemble in militia companies. The broad militia mobilization did not actually stop the British from returning to Boston. Thus, Revere’s warning might not have been necessary to how things worked out at the end of the day.

Let’s imagine that Revere wasn’t able to complete his ride—that as he traveled from Charlestown into Cambridge a British patrol succeeded in capturing him, as one nearly did. Then Revere would not have alerted Patriots in the towns along his route through Medford to Lexington. He would not have arrived in Lexington shortly after midnight with a warning for John Hancock and Samuel Adams. He would not have headed further west to Concord. How would subsequent events have been different?

Hancock and Adams would still have received Dr. Warren’s message because William Dawes arrived with it about half an hour after Revere. Dawes’s arrival would have prompted a general militia alert in town, as Revere’s did. Indeed, some militiamen were already active. “Early in the evening” Sgt. William Munroe had mustered an eight-man guard at the parsonage where Hancock and Adams were staying, having heard from a young local named Solomon Brown that there were “nine British officers on the road,” carrying arms.[i]

Furthermore, there were at least four hours between Dawes’s arrival and dawn. The Lexington militia and the people at the parsonage discussed the news from Boston at length. They sent messengers out to other communities. Brown and two other riders headed west to Concord (British officers stopped them). Other men rode east to confirm whether troops were coming along the road from Boston. Capt. John Parker had more than enough time to assemble his men. In fact, at some point between three and four o’clock he dismissed them to catch some sleep nearby.[ii]

In those hours, Hancock argued with Adams, the Rev. Jonas Clarke, his aunt, and his fiancée about whether he should leave Lexington or face the enemy. Eventually that crowd convinced Hancock to leave. Given the class lines of eighteenth-century society, it seems unlikely that the voice of a mechanic like Revere would have been crucial in that discussion. Eventually Hancock and his companions would still have rolled out of Lexington.

But let’s imagine that Hancock had insisted on staying in the Lexington parsonage, hunkered down with a militia guard. In that case, the British troops would have passed right through town on their way to Concord. That’s because Gen. Thomas Gage never ordered his officers to search for Hancock and Adams. Gage’s intelligence files and orders were entirely focused on the weapons that the Massachusetts Provincial Congress had amassed in Concord and elsewhere.[iii] No British soldiers went near the parsonage. Revere’s original warning to Hancock and Adams was unnecessary.

Might Revere have had a bigger effect to the west? After he and Dawes delivered their messages at the parsonage, they decided to ride to Concord. Along the way, they met Dr. Samuel Prescott and started to alert more householders that the regulars were on the march. Let’s imagine that, if Revere never showed up, Dawes didn’t choose to go on. And Dr. Prescott, riding home from a visit with his fiancée, was stopped by British officers. In sum, let’s imagine that the news of regulars coming out of Boston never reached Concord.

Again, that may not have had a big effect because Concord was already on alert. Revere had brought militia colonel James Barrett a general warning from Boston a couple of days before. The Barretts were already moving the cannon, gunpowder, and other military supplies from their farm to more remote hiding-places.

To be sure, the whole Concord militia didn’t assemble until Dr. Prescott rode into town around two o’clock in the morning. However, as at Lexington, there was a significant stretch of time between the first alert at Concord and when its militia company had to face the British troops. In fact, when those regulars arrived between eight and nine o’clock in the morning, the Concord militia companies pulled back to Punkatasset Hill, a mile north of the town center, before moving to a field above the North Bridge.[iv]

Our public memory emphasizes the minutemen, ready at a minute’s notice to defend the countryside, but once those troops assembled they followed more typical military orders: “Hurry up and wait.” Two hours passed after the regulars’ arrival. Militiamen from other towns joined the Concord companies. Only when they saw smoke rising from the Concord town center did those Middlesex County companies move against the British companies beside the North Bridge. That clash produced the first deaths among the regulars, and more casualties among the provincials. And then the militia companies withdrew again to another high ground. The British force remained in Concord for another two hours.

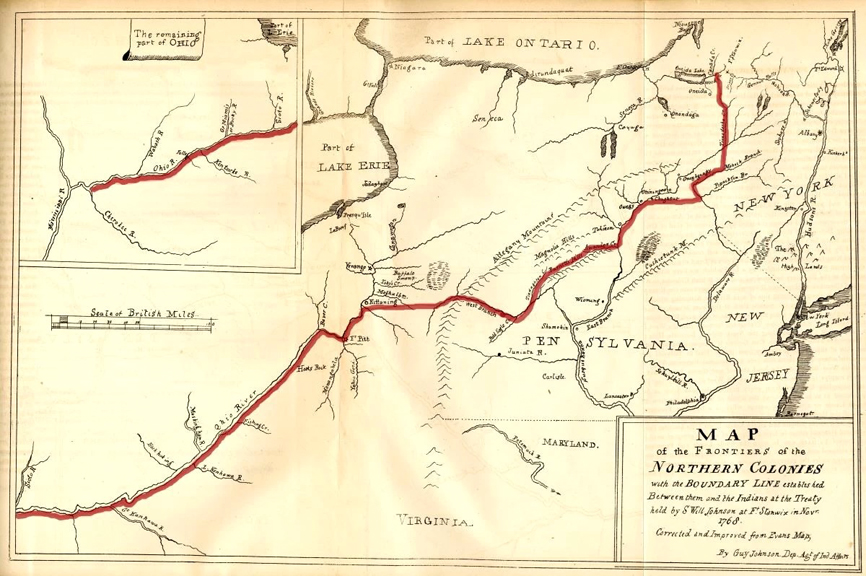

Thus, in all there were six hours between when the British marched west out of Lexington and when they started their withdrawal east from Concord—plenty of time for locals to spread the word of the fatal shots on Lexington Common and for a significant number of militia companies to assemble and march. Only then, in the afternoon of 19 April, did the Massachusetts forces start their concerted attack on the British column.

It’s certainly true that without Revere’s early warning, especially along his route to Lexington, the alarm would not have spread as far and as fast as it did. But in the early afternoon the militiamen who engaged the British came from towns close to Lexington and Concord. They were probably close enough to hear the reports about the British officers on the roads and the killing on Lexington Common. In short, most of those companies would probably have mustered even without Revere. There would still have been enough militiamen to inflict significant damage on the tired British column as it returned east.

When those regulars got back into Lexington, they were very pleased to find their reinforcements under Col. Percy. He used field artillery to keep the provincials at a distance, allowing time for another stop. It was after 3:00 when Percy led the combined British forces east from Lexington again. During their march through Cambridge to Charlestown, they faced a wider array of Massachusetts companies, both in front and in the rear.

Would all of those militiamen have arrived in time for the fighting if Revere had been stopped early in his ride? Another messenger left Charlestown at the same time as Revere, headed north, and spread the news to the New Hampshire border by 2:30 A.M. However, Revere himself or men he talked to carried the alarm to other towns north of Cambridge.[v] It’s therefore difficult to say which militia companies would have been left out of the fight if Revere had been stopped.

The alert certainly reached Danvers, Beverly, and Lynn in Essex County in time for their companies to respond and for some of their men to set up an ambush in west Cambridge (now Arlington). Unfortunately for those overenthusiastic provincials, the British light infantry flanked their position and killed eleven men.[vi]

The British march through west Cambridge was the bloodiest for both sides, and it probably would have been easier for the regulars if their scouts had halted Revere seventeen hours before. However, while that afternoon fighting was a matter of life and death to men on both sides, it had only a limited effect on the strategic situation at the end of the day. By then the most crucial events of the day had already occurred.

If we take the long view, the outcome of the British march on 18-19 April would probably have been the same:

- The British troops would still have failed to destroy the Provincial Congress’s most important supplies in Concord. With most of those arms already moved, the British mission was a failure before it began.

- Somewhere along the march, miles inside unfriendly territory, the regulars would have encountered local militiamen. In the high tension that had prevailed in Massachusetts since the Powder Alarm of September 1774, that encounter would probably have led to shooting, followed by a sustained clash with significant numbers of casualties.

- The British troops would still have completed their withdrawal to Boston; it’s not clear the provincials ever really wanted to block that movement.

- In the evening of 19 April the much larger provincial forces would still have put British-occupied Boston under military siege to prevent any further march.

- Both sides would have felt that the other had started the violence and/or carried it out brutally and unfairly. The American cause would be energized by a sense of grievance, and Crown officials would see the provincials as fanatics—just as events really did turn out.

Paul Revere was undoubtedly brave, shrewd, and tenacious during his ride on 18-19 Apr 1775. His adventure makes a very dramatic story, even without Longfellow’s embellishments. That same drama may lead us into thinking that Revere must have been very important to the battle that followed. But larger movements of people were already under way, or would almost inevitably have occurred without him. When we step back and imagine the day without him, Paul Revere’s ride may not have changed events all that much.

[Featured Image at Top: “Painting depicting the midnight ride of Paul Revere” – 1937. Artist A.L. Ripley. Source: National Archives]

[iii] Thomas Gage Papers, American Series, Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Gage’s draft and final orders for the march can be read in Allen French, General Gage’s Informers: New Material Upon Lexington and Concord, Benjamin Thompson as Loyalist and the Treachery of Benjamin Church, Jr. (Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press, 1932), 29-32.

8 Comments

Mr. Bell, I would agree with your analysis that previous knowledge of General Gage’s intentions were well known by the Patriot leadership and that troop movements within Boston in preparation for the actual mission were also reported by various methods. My one differing point would be regarding your view that Revere’s role would be diminished due to class consideration. Revere was a longstanding and trusted member of the Sons of Liberty, and more importantly a middle level, or better, leader in the intelligence element, the “Mechanics”. Thus his role, in my opinion, would have carried weight regardless of the class distinction.

Thank you for yet another interesting article.

Thanks for the comment. I agree that John Hancock and Samuel Adams knew Paul Revere well by 1775, and considered him a political colleague—of a sort. There’s an anecdote from a couple of years before about James Otis asking Revere and printer John Gill to watch the door while he discussed a political matter with John Adams. I doubt Hancock and Samuel Adams were that blunt, but I think there would still have been a class divide between Harvard-educated gentleman and a craftsman who sold his wares to them. They would have valued Revere’s information, but I’m not sure they would have asked for his advice.

I suspect Hancock saw his decision to leave the parsonage as a conflict between two genteel responsibilities. Should he, until recently ranked as a colonel in the militia, command citizen-soldiers in the field? Or should he behave as part of “the cabinet,” as Samuel Adams declared, and leave to ensure civil government remained? On that question, I think he would have taken the advice of other gentlemen—a social rank Revere didn’t reach until after the war.

Then again, Hancock’s best friend as governor was a hatter, so he might have had a more populist touch.

John,

As usual, well done treatment of another interesting issue. I agree that there were indeed many people already afoot before Revere even started out.

As the Journals relate, there was a flurry of activity by the Committees of Safety and Supplies on April 17, including the transfer of quite a bit of materiel being disbursed out to several towns (see, pgs. 515-518). For the town of Groton, that meant that four cannon were designated to be moved there, and they arrived the afternoon of April 18.

This was a surprise to the town’s minutemen and they began to wonder what was happening. They had a quick meeting and took a vote on how to proceed, with some deciding to remain in town awaiting further developments while nine others struck out immediately for Concord, “We traveled all night, carrying lighted pine torches part of the way, and we reached Concord at an early hour of the morning.” Those men were not at Lexington, but reportedly were present at the North Bridge. (see, http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002053503604;view=1up;seq=365)

So, as you note, people were already gathering before word got to that part of Middlesex County and the redistribution of warlike materiel surely got the attention of many in other towns. Revere probably just confirmed a lot of what the locals already knew.

Thanks for the comment and pointer, Gary. Yes, one of the goals of this article was to shine more light on the broad-based mobilization in the Massachusetts countryside. The alarm system worked sort of like the internet, with messages being routed through lots of channels and servers rather than along one designated line that could break or be cut.

Excellent and enjoyable analysis!

A very provocative description of the back story on Paul Revere’s ride, thanks!

I realize this is a bit off topic: does anyone know what happened to the bodies of the British soldiers who were killed? What happened to the wounded? Anybody take care of them? Were they taken prisoner or returned to Boston? Who cared for the dead/wounded colonials?

More on my blog:

http://historybottomlines.blogspot.com/

There are multiple burial sites for British soldiers along the route of their withdrawal from Concord to Arlington. At first those sites were kept quiet, but currently they’re marked with stones and plaques and often honored in ceremonies.

The wounded were cared for by local doctors. At least one wounded regular died, but others were exchanged in May for locals taken prisoner. And some prisoners/deserters simply melted into New England society.

Because the British army left the field, locals faced no opposition in burying their own dead and treating their own wounded. At the Battle of Bunker Hill, the British won the field and captured a number of wounded provincials. The military authorities put those prisoners into the Boston jail. Many died, although whether that was because of substandard care or simply standard care is not clear.

Thanks!