It was an unfortunate expedient, but one that had grown unavoidable. On September 8, 1776, George Washington penned a lengthy report to Congress in which he detailed the pending decision to abandon New York City. Although Washington acknowledged that quitting New York would clearly have an adverse affect on the American war effort, he summed up the magnitude of his unenviable decision with a stark admission. “On every side there is a Choice of difficulties and every Measure on our part…to be formed with some Apprehension that all our troops will not do their duty.”[1]

Subsequent to the crushing American defeat on Long Island during the final week of August, such fears regarding the reliability of his troops were by no means groundless. By the middle of the month Washington had begun the transfer of his demoralized army to Harlem Heights, a far more defensible position that commanded the northern reaches of Manhattan Island. He likewise did his best to guard the island’s eastern flank from an expected British invasion, but such a dreaded move materialized on the morning of September 15. A staggering naval bombardment scattered American troops on Kip’s Bay in short order, and landing parties seized the rebel lines largely uncontested. The wholesale stampede of Washington’s inexperienced troops resulted in one of the most embarrassing episodes of the war. Private Joseph Plumb Martin, a private serving in a regiment of Connecticut state troops, joined the pell-mell retreat but candidly explained that “The demons of fear and disorder seemed to take full possession of all and everything on that day.”[2]

Exasperated by his troops’ lackluster battlefield record but intent on ascertaining British intentions, Washington ordered out a scouting party for the morning of the 16th, and called on some of his most reliable troops, a company of New England rangers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton. A native of Connecticut, veteran of the French and Indian War, and hero of Bunker Hill, Knowlton was an officer who never called “‘Go on, boys!’ but always ‘Come on, boys!’” recalled one of his men.[3] The colonel was to take his men south from Harlem Heights, cross a narrow valley known as the Hollow Way, and probe British positions thought to be in the vicinity of Bloomingdale close to the Hudson River.

Washington, headquartered at the home of Tory Colonel Roger Morris, woke early on the morning of Monday the 16th and quickly got to work, penning a report to Congress which detailed the embarrassing debacle of the previous day. The army’s current position, he wrote, was strong enough that “the enemy would meet with a defeat in case of an attack, if the generality of our troops would behave with tolerable resolution.” But after repeated battlefield drubbings, Washington dejectedly confessed that “experience, to my extreme affliction, has convinced me that this is rather to be wished for than expected.”[4]

Before he could finish the report, however, he was informed that three British columns were advancing on the American position. Washington immediately ordered Joseph Reed, his adjutant general, to investigate. Reed rode out beyond the lines and found that although reports of a large British demonstration were unfounded, Knowlton’s Rangers were engaged in a lively skirmish with the enemy. The Connecticut men had headed out before dawn and probed about a mile south before running into British pickets who opened fire and roused an advance post of light infantry. Soon pressed by superior numbers, Knowlton drew his men off in good order and made a fighting withdrawal, halting behind a stone wall to engage in a sharp firefight. When the rangers were forced to fall back, Reed joined Washington, who had just arrived on the field.

As the two men conferred, they were greeted by a familiar sight: American troops in full flight before the enemy. As Knowlton’s men scampered across the Hollow Way, British light infantry followed close on their heels and, wrote Reed, “in the most insulting manner sounded their bugle horns as is usual after a fox chase. I never felt such a sensation before – it seemed to crown our disgrace.”[5]

The rangers were pursued by some of the finest troops at Howe’s disposal, elements of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of Light Infantry as well as the famed Black Watch, the 42nd Regiment of Foot. When Knowlton’s winded men ran into the safety of the American lines, Washington was finally able to get a better grasp of the tactical situation. Although only a portion of the Britons exposed themselves to view, the rangers announced that the enemy party “consisted of about three hundred, as near as they could guess,” hidden behind a stand of trees beyond a hill to the front. The light infantry’s ill-advised use of a fox-hunter’s call was clearly an insulting gesture that demanded a response. By nature an inherently aggressive field commander, Washington accommodated and quickly decided to pounce on the redcoats, who had clearly rendered themselves vulnerable by advancing so far beyond their own lines.[6]

He planned not to drive the redcoats back, but to destroy them in detail; as he later put it, “I formed the design of cutting off such of them as had or might advance to the extremity of the wood.”[7] To the field in his front, Washington would throw out a feint, about 150 volunteers primarily drawn from General John Nixon’s brigade of Massachusetts and Rhode Island troops, to fix the enemy in position. While the redcoats were thus occupied, another column, consisting of Knowlton’s Rangers and three rifle companies of the 3rd Virginia under Major Andrew Leitch, would swing around the enemy’s right and attack from the rear. While Knowlton readied his rangers, Colonel Reed, who was to accompany the flanking party as a guide, rode off with orders for Leitch to bring up his troops.

When the decoy party advanced into the Hollow Way, British troops were quickly lured into the open, and the bulk of Nixon’s Brigade was advanced in support. Captain John Chilton, a company commander in the 3rd Virginia, recalled that the redcoats were seen “peeping from their heights over the fencings and rocks and running backwards and forwards.” The British expected to receive an attack up the hill, but when the Americans halted the British, wrote Chilton, the British “came down skipping towards us in small parties,” eventually taking up positions behind an overgrown fencerow. The Americans were under strict orders to hold their fire, but when the enemy reached the distance of 250 or 300 yards a jittery young officer prematurely opened fire and the entire line, from right to left, unleashed a ragged volley.[8]

Colonel George Weedon of the 3rd desperately shouted for the men to hold their fire, but could not be heard above the din of musketry; even Captain Chilton thought that Weedon was calling for the men to “keep up our fire.” The troops delivered “about four” volleys, wiped their muskets, and coolly sat down in their ranks. It was no mean feat for relatively green troops. “We…let the enemy fire on us near an hour,” recalled Captain Chilton, who praised his men in a glowing letter to his friends in Virginia. “Our men observed the best order, not quitting their ranks, though exposed to a constant and warm fire…they behaved like soldiers who fought from principle alone.”[9]

While the British were thus occupied, Knowlton and Leitch succeeded in working around their right largely undetected, but the inescapable fog of war frustrated the attack. Their line of march brought the troops not to the British rear, but flank. Colonel Reed thought that the mistake was occasioned by over-zealous pressure on the British front as well as well-meaning but confused American officers who misdirected Knowlton’s column.[10] Although the impact of the attack was somewhat blunted by the mishap, it was by no means inconsiderable. Knowlton’s troops drove hard into the enemy and unleashed a punishing fire; during the sharp exchange of gunfire, Leitch was struck twice but stayed on his feet, urging his men to press the attack. A third wound finally brought him down, and the major was carried from the field mortally wounded and in considerable pain; he had taken two balls in the abdomen and one in the hip.[11]

Not long after Leitch was carried from the field, Knowlton fell with a ball in the small of his back. A nearby officer, Captain Stephen Brown, rushed to his side and asked the colonel if he was badly wounded. “Yes,” Knowlton replied, “but I do not value my Life if we do but get the Day.” Brown ordered two men to carry Knowlton from the field, but observed that the stricken colonel “seemed as unconcerned and calm as tho’ nothing had happened to him” and urged Brown to maintain pressure on the British.[12] Knowlton was carried to the rear, where Joseph Reed placed him on his own mount; the colonel’s wound was clearly mortal. “When gasping in the agonies of death,” remembered Reed, Knowlton could think of little more than victory, and “all his inquiry was if we had driven in the enemy.”[13] He was dead in an hour.

Although the rebels had failed to strike the British in the rear and block their line of retreat, it was clear that the enemy was left staggered by the attack and Washington, sensing victory within reach, committed fresh troops to the fight, hurriedly sending up a mixed bag of reinforcements. As a regiment of Connecticut state troops arrived in the Hollow Way, the British were apparently attempting to form up in better cover. Private Joseph Plumb Martin recalled that the redcoats “were entering a thick wood, a circumstance as disagreeable to them as it was agreeable to us at that period of the war.”[14]

Such overwhelming pressure afforded the enemy little chance to regroup. Senior officers watched in admiration as the Maryland regiments of colonels Charles Griffith and William Richardson went into action. They were green troops, but the ferocity of their attack shattered the British line. “Tho’ young,” observed Lieutenant Colonel Tench Tilghman,” the Marylanders “charged with as much bravery as I can conceive.”[15] British troops broke in considerable confusion, but their officers succeeded in rallying them on a good position a little farther to the south, in a buckwheat field atop high ground.

What ensued was a stand-up fight that lasted nearly two hours; the tremendous crash of musketry could be heard for miles. The British likewise fed troops into the fight, sending up support from the British and Hessian grenadier battalions and the 33rd Foot, as well as a company of Hessian Jaegers and a pair of three pounders. However, it is likely that British reinforcements arrived on the field in piecemeal fashion; considerably outnumbered and unable to form an effective response to the American juggernaut, Crown forces again broke for the rear.

Apprehensive of a British counterattack, Washington wisely reckoned that he had best pull his men out, and dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Tilghman with orders for the troops to disengage. “We remained on the battle ground till nearly sunset,” recalled Private Martin, “expecting the enemy to attack us again, but they showed no such indication that day.”[16] Indeed General William Howe harbored no desire to bring on a general engagement. His troops had clearly been chewed up in the unexpected clash with the rebels, and he cast blame for the debacle on his light infantry, who had brought on the action “without proper discretion.” Sir Henry Clinton was unambiguous in his assessment. “The ungovernable impetuosity of the light troops drew us into this scrape.”[17]

The grim cost of such a victory became readily apparent the following day. An American fatigue party under the command of Lieutenant Samuel Richards headed out into the Hollow Way on the “mournful duty” of burying the dead. Some of the corpses had sustained ghastly head wounds and rumors quickly spread that they had been bludgeoned by Hessian troops.[18] “There were thirty three bodies found on the field,” wrote Richards, “they were drawn to a large hole which was prepared for the purpose and buried together.”[19] All told, the Americans lost about 33 men killed and perhaps 100 wounded. The British no doubt got the worst of it. At least 16 redcoats were buried on the field and a deserter reported 89 wounded; their actual casualties were no doubt higher. One officer reported finding 60 large bloodstains on former British positions and Private Martin wryly offered that the actual figures would remain elusive “as the British were always as careful as Indians to conceal their losses.”[20]

In the American camp, officers noticed that in the aftermath of the action at Harlem Heights their men experienced a palpable and desperately needed shift in morale. Novice Continentals who had hitherto known only embarrassing defeat were clearly elated that they had, for the first time during the war, put some of the King’s best troops to flight. It had by no means been a battle of epic proportions, but Washington saw that the fight had produced “a surprising and almost incredible effect upon our whole army…every visage was seen to brighten, and to assume, instead of the gloom of despair, the glow of animation.”[21] George Weedon, whose Virginians had coolly exchanged volleys with redcoats in the Hollow Way, was more blunt in his assessment of the fight’s effect on the enemy. “Upon the whole,” he reported, “they got cursedly thrashed.”[22]

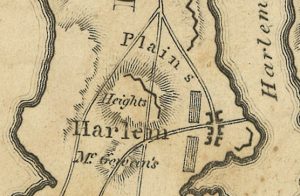

[Featured Image at Top: Detail of 1776 map of the British Armies in New York. See full map.]

[1] Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six: The Story of the Revolution as Told by its Participants (reprint, Edison New Jersey, Castle Books, 2002), 460. Letter, Washington to President of Congress, September 6, 1776.

[2]Joseph Plumb Martin, Memoir of a Revolutionary Soldier (reprint, Mineola, NY, Dover Publications, 2006), 21.

[3] Barnet Schecter, The Battle For New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution (New York, Walker & Company, 2002), 197.

[4] George F. Scheer and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats (Mentor, 1959), 208.

[5] William B. Reed, ed., Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed (Philadelphia, Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847), vol. 1, 237. Letter, Reed to his wife September 22, 1776.

[6] Henry Phelps Johnston, The Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16,1776: With a Review of the Events of the Campaign (New York, The Macmillan Company, 1897), 130-131, 176.

[7] Johnston, Harlem Heights, 133.

[8] Schecter, Battle for New York, 198-199.

[9] Schecter, Battle for New York, 199.

[10] Reed, Joseph Reed, 237.

[11] Johnston, Harlem Heights, 172.

[12] Johnston, Harlem Heights, 155.

[13]Reed, Joseph Reed, 238.

[14] Martin, Memoir, 25.

[15] Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 470. Letter, Tilghman to his father, James Tilghman, September 19, 1776.

[16] Martin, Memoir, 25.

[17] Johnston, Harlem Heights, 89.

[18] Johnston, Harlem Heights, 155.

[19] Thomas Addis Emmet, The Battle of Harlem Heights, (By the Author, 1906), 1-2.

[20] Martin, Memoir, 25, Schecter, Battle for New York, 201.

[21] Schecter, Battle for New York, 201.

[22] Commager and Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six, 471. Letter, Weedon to John Page, President of the Virginia Council, September 20, 1776.

5 Comments

Thanks for an engaging article about this small, but memorable action for those of us New York City dwellers who read about the war. Most NYers go about their business without the slightest awareness how the topography of Manhattan radically changed from one end of the Island to the other and from East River to the Hudson. If you go to Harlem Heights (today’s Morningside Heights or West Harlem) and let the streets and buildings drift away, you can easily appreciate how well-situated Washington’s army was placed. The Morris mansion referred to in the article is the Morris-Jumel Mansion and is a small, but interesting, well run and growing group intent on preservation. It’s location on a small bluff alongside a cliff further illustrates the land at the time of the battle. I also commend Joshua for his sources, including Schecter’s book which is the best volume on the subject I’ve read.

Col. Knowlton’s involvement in this battle demonstrated his and his unit’s aggressiveness and courage in combat. His unit, by that time known as “Knowlton’s Rangers”, is considered by the U.S. Army as its first intelligence unit and is the reason that the year 1776 is on the army intelligence emblem. However, often forgotten is that he also accepted Nathan Hale as a volunteer spy for a mission with little if any planning, poor operational security from the start and with a dubious mission objective. While for a very brief period he provided some useful tactical reconnaissance intelligence, his skills were clearly more in the combat command field.

This is an excellent article, but reliance solely on American sources introduces some bias.

The British light infantry did not sound hunting horns to be insulting; those horns were used for signaling, just like cavalry bugles. Infantry had traditionally used drums for that purpose, but those instruments were unwieldy for the fast, fluid movements of the light troops. In 1772, shortly after light infantry companies were permanently established in British regiments, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland gave recommendations for them including, “All Officers Commanding Companies, or any body of Light Infantry, are to fix upon signals for extending their Front to the Right or to the Left, or to both Flanks, or to Close to the Centre, to retire, or to advance, and these signals must be made by a loud whistle, a posting horn, or some other instrument capable of conveying a sufficient sound to be heard at a considerable Distance, and the stoutest of the Drummers is to be taught to sound these instruments by directions from the Commanding Officer.” [Rules and Orders for the Discipline of the Light Infantry Companies in His Majesty’s Army in Ireland. Given &c. the 15th Day of May 1772]

A few years after the Harlem Heights battle, a British officer wrote a letter home mentioning “the first sound of the bugle horn, which the Light Infantry used instead of a drum. it resembled a huntsman’s horn, and by different notes, easily distinguished, loudly expresses the different words of command, to be heard at two miles distance; twelve or fifteen of them together make the most lofty warlike music in the world.” [Letter written by Lieutenant Colin Campbell, 74th Regiment, New York, 20th November, 1780, in The Story of the Highland Brigade in the Crimea Founded on Letters Written During the Years 1854, 1855, and 1856, by Lieut. Colonel Anthony Sterling (Remington & Company, London, 1895)]

As for allegations that the British understated casualty figures, such claims are often made but there is no evidence to substantiate them. Comparing reported British casualties to muster rolls and other corroborating documents proves the casualty figures to be quite accurate. Eyewitnesses on each side tended to overestimate the casualties of their opponents.

The initial pursuit of the Rangers by the 42nd Highlanders is not supported by documents in the Gen. Thomas Stirling Papers at the Regt. Headquarters. The 42nd Regt. was split into two provisional battalions on arrival in America and only one battalion (of 3 companies) was heavily engaged at Harlem. A memorial for Stirling was prepared on the 1776 campaign which describes the battle as follows:

Memorial

Lt Col: Stirling 42d Regt

…the 15th Sept … next morning the L.I. having discovered a body of the Rebels turn out to attack them & drove them before them sending to the 42’d to support them unfortunately the Lights through too much ardour pursued too far untill they found themselves oppossed by Washingtons Army the 42d marched up to bring them and one [battalion] taking post on an advantageous ground the other [battalion] marched up to the Height of [Vanderwater’s] to cover the Lt Infy as they came off which they effectually did, and tho the Rebels advanced in great force & if they came to the ground they were ordered to in great order bringing of all their killed and wounded the other Battn maintained itself on its Ground till the Rebels retreated The Regt lost 1 Offr K 2 W & 46 K&W ___

Source: “Short account of the movements and engagements of the two battalions of the 42nd from 22nd August to 16th December 1776” (Addressed to Col T Stirling commanding 42nd Royal Highlanders.) BWRA 0398 Stirling Papers /5, Archives, Regimental Headquarters, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) Balhousie Castle, Hay Street Perth PH1 5HR (Note: pages one and two reversed to correct error by original author.).

As a further observation regarding the Light Infantry’s sounding bugle horns following their pursuit of Knowlton’s reconnaissance party, while Joseph Reed believed the bugle calls were intended as an insult, it is clear that others in the American line perceived the calls differently.

Lieutenant Joseph Hodgekins wrote,

“the Enemy Halted Back of an hill and Blood [blowed] a french Horn which whas for a Reinforcement.”

Major Lewis Morris, Jr, recounted “the Enemy advanced upon the Top of the Hill opposite, to that which lies before Deyes’s Doare,[SIC ] with a Confidence of Success, and after rallying their Men by a Buegil Horn and resting themselves a little while, they descended the Hill with an Intention to force our Flanking Party..”

(Both quoted in Henry Johnson’s ‘The Battle of Harlem Heights’, 1897)

It does seem that, down the years, undue emphasis has been given to Reed’s subjective impression, with commentators elaborating imaginatively on the subject, despite no apparent understanding of fox-hunting or huntsman’s calls- let alone light infantry drills in the 1770s.

Perhaps the appeal of the legend lies in the apparent hubris of exulting over an enemy who was not as cowed as the overconfident British believed. The aggression which numerous commentators claim this provoked on the part of Washington and his troops is seen as a fitting nemesis, inspiring an unexpected check to the British advance and a much needed boost to American morale. That last, at least, is true.