For a few terrifying minutes the air was filled with the sound of gunshots, war-whoops and the screams of the dying. It was over quickly. Within plain sight of Fort Laurens, but beyond musket range, 19 members of a work party were ambushed and overwhelmed by Indians and British. Seventeen were killed outright, their scalped bodies lay clearly visible to the fort’s defenders.[1]

Fort Laurens named for President of the Continental Congress Henry Laurens, stood on the west bank of the Tuscarawas River one mile south of present day Bolivar, Ohio. It was built in the late fall of 1778. Originally the plan was to march through present day Ohio, attack the Indian villages along the Sandusky river then proceed on to attack the British at Detroit. After numerous delays and scaling down of the mission the Patriot forces left their base on the Ohio River and proceeded as far as the site of Fort Laurens where they intended to stay the winter then move on to the Sandusky River 90 miles to the northwest in the Spring of 1779.

Supplies of everything from food, clothing and even nails were short almost immediately. The 152 men and 20 officers faced a cold, bleak winter of short rations. Rumor had reached Colonel Gibson, the fort commander, that hostile Indians from the Sandusky region were planning on attacking the fort. However, on the morning of February 23rd he had no idea that his fort was surrounded by 180 British and Indians.

The work party walked into the ambush on an open plain just south of the fort. The seventeen men killed lay where they fell; the two men captured were taken away. One was released after the war. The fate of the other is unknown.

The attackers were not powerful enough to directly assault the fort. However, they laid siege and tried to starve the garrison into surrender. They almost succeeded. The men were reduced to literally eating their roasted moccasins and belts.

After a few weeks the Indians began to tire of the siege and drift away. They had less incentive to take the fort than the men inside had to hold out. A relief force arrived on March 23 and the siege was raised.

The bodies of the ambush victims, now decayed and gnawed by wolves, were collected and buried in a mass grave in a rough cemetery 200 feet west of the west side of the fort near others who had died of various causes. There, the bodies would remain for two centuries.

In the 1970’s during archaeological work the fort cemetery was discovered and along with it the remains of the ambush victims. A thorough skeletal analysis “examining the variety and pattern of lesions[2] found on the victims of the ambush” was published in 2003.[3] The opportunity to examine the remains of Revolutionary War casualties is very rare.

In the skeletal analysis it was determined that one grave contained 15 individuals. Of these 15, 13 were buried in a group. The 13 buried together are believed to be victims of the ambush of February 23, 1779. Only 12 of the 13 skulls were complete enough to study.

Some of the individual remains included small bones of the hands and feet and others only had large bones present. The missing bones may be due to decay or the scavenging of animals. It should be remembered that the ambush victims were unburied for over four weeks.

All bones were examined for evidence of gunshot wounds. Despite being examined by x-ray no evidence of gunshot wounds was found on any of the bones. Neither lead fragments nor lead wipe were found. Of course, it is quite possible that a victim was shot and the lead bullet failed to contact any bone. In addition, it is possible that traces indicating gunshot wounds may have been on the bones that are missing.

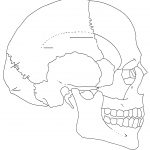

The bones were also examined for evidence of blunt force trauma which would be caused by a “relatively low-velocity impact over a relatively large surface area.” The brutality of the attacks was unmistakable. Five of the twelve skulls had a least one blunt force lesion. All such wounds were either on the right side or on the midline of the skull. Four of the six blunt force fractures were circular with approximate diameters of 30 mm ( 1 3/8 inches).

Sharp force trauma can be divided into two groups: coarse and fine lesions. Coarse lesions can be caused by a heavy bladed weapon chopping or stabbing. These weapons leave a broad bevel to the cuts on the bones. Fine lesions are those made by sharp bladed weapons used for cutting, leaving a narrow, shallow bevel in the bone.

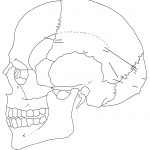

All but one of the skulls show evidence of coarse lesions. There were a total of 28 coarse lesions on the 12 skulls. The blows can be broken down as 4 on the front of the skull, 9 on the right side, 11 on the left side and 4 on the back of the skull. 23 of the 28 were delivered perpendicular to the surface of the skull. Five blows were determined to be glancing.

All 12 skulls had fine lesions, those caused by thin, sharp weapons used to scalp the victim. It is interesting to note that only one fine lesion was across the front of one skull. All other fine lesions were on the sides and rear of the skull. There are various forms or techniques involved in scalping. [4] These cuts indicate that the head was held by the attacker’s left hand while the right cut around the hand with a knife thus enabling the left hand to rip off the scalp.

One individual received a blow to the lower rear of the skull with such force that the blade passed through the brain and damaged the interior of the right side of the skull. This same individual had 3 other coarse lesions on the underside of the skull. This individual also received 3 blunt force lesions for a total of seven severe blows to the head.

Nine of the 12 skulls had more than one coarse lesion. Five had three or more. One individual received five such blows, all of which penetrated the bone. Five of the 12 skulls had “at least one blunt wound and one coarse wound.”

Clearly, the attacks on these men were extremely violent. In every case one or two blows from the hatchet or war club would kill. One may speculate that the excessive force, amounting to mutilation, was thought to be a terror tactic to intimidate those who would find the bodies, or in this case, those remaining inside Fort Laurens. For the modern researcher, however, the bones of the victims provide an insight into the violence of frontier combat during the American Revolutionary War.

After the siege was raised by the relief force the fort was garrisoned until August 1779 when it was abandoned. The Indian villages along the Sandusky River were never attacked nor was Detroit. The venture into the Ohio country was a complete failure.

Today a museum stands on the site of Fort Laurens. The outline of the fort is cut into the ground and filled with mulch to enable the visitor to see the size and shape of the fort. The original east wall of the fort was near the Tuscarawas River. However, in the mid 19th century the Ohio canal was dug between the river and the site of the fort destroying the location of the fort’s east wall. In the 1960’s, Interstate 77 was constructed requiring the Tuscarawas River to be permanently diverted to the east. Today the section of I-77 that passes east of the fort occupies the area that was the Tuscarawas River in 1779. The Museum is open May 1 – October 31 from 10-5 Wednesday to Saturday. On Sundays and holidays it is open 12-5.

The remains of one unidentified man from the old fort cemetery has been permanently sealed within a Tomb of the Unknown Patriot of the American Revolution near the original burial site. The remains of the others, including the victims of the ambush, were placed in a crypt within the museum in 1992.

[Featured Image: Rendering of Fort Laurens. Source: Friends of Fort Laurens]

[1] The history of Fort Laurens can be found in Thomas I. Pieper, and James B. Gidney, Fort Laurens 1778-1779, the Revolutionary War in Ohio, (Kent, OH, Kent State University Press, 1976).

[2] A “lesion” may be defined as any localized, abnormal structural change in the body

[3] Unless otherwise noted all discussion of the remains is from: Mathew A. Williamson, Cheryl A. Johnston, Steven A. Symes, and John J. Schultz, “Interpersonal Violence between 18th Century Native Americans and Europeans in Ohio,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 122 (2003): 113–122.

[4] A grimly fascinating analysis of scalping can be found in: Gabriel Nadeau, “Indian Scalping, Technique in Different Tribes,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 10 (1941): 178-194. For a discussion of treating living scalping victims see: Hugh T. Harrington, “How to Treat a Scalped Head,” Journal of the American Revolution [allthingsliberty.com], May 14, 2013.

4 Comments

A fascinating article. Forensic anthropology and archaeology are sciences that help inform the historian. There are so many sites, in New York alone, that deserve the attention of these two sciences to further enlighten the public. It was great to see Gov. Cuomo designate $60m for the “Pathway through History” program that will highlight NY history, including the Colonial and Revolutionary War periods. Stimulating tourism will stimulate more interest in reading about the places and events. I suspect any visitor to Fort Laurens will “buy the book” and note the section “For further reading.” Well, we can always hope.

Great article, Hugh! Lest one forget the savage brutality that some Revolutionary War battles were fought, your article reminds us all again. Not all were “just” musket balls at 60 yards. I like the fact that the Patriots were discovered and given a proper heroic burial including the single soul placed in a Tomb of the Unknown Patriot of the American Revolution. Bravo.

Brutal is right. Ghastly. I’m trying to locate the article by Dr. Williamson online. I’ll post that when/if I get it. Reading the report of the anthropologists is grimly fascinating.

Steven – I’m a great believer in historic tourism. Every state and locality ought to pursue such programs.

Great Article. Very interesting.