In 1776, John Cadwalader was a thirty-four-year-old merchant and prominent member of the Philadelphia gentry who had risen to command the volunteer militia known as the Philadelphia Associators. In his capacity as a militia colonel, he would play a distinctive—and today largely unappreciated—role in what historians have termed the “Ten Crucial Days” of the Revolutionary struggle, which reversed the momentum of that contest during the winter of 1776-1777. At a moment when the rebellion appeared to be teetering on the precipice of final defeat, Cadwalader arguably made his greatest contribution to what George Washington termed the “glorious Cause”[1] of American independence. Like his friend Washington, he was drawn to the Patriot enterprise by a perceived threat to his economic interests; and like the more senior Virginia planter, the young Philadelphia merchant enjoyed the finer things in life but was willing to risk his own in that endeavor.

A Prosperous Beginning

The family patriarch, the first John Cadwalader (1677-1734), was born in the town of Bala, Merioneth County, Wales, and left for the New World in 1697, seeking to freely practice his Quaker religion. John wed Martha Jones (1679-1747) in 1699, and the couple had three daughters and a son, Thomas. John began his professional life in America as a schoolteacher in Merion, Pennsylvania, but soon moved to Philadelphia. He inherited money from his father and uncle, and established himself as a merchant and a man of civic affairs, which included service on the Common (City) Council for fifteen years. Upon his death, John left his family substantial money and land.

Dr. Thomas Cadwalader (1707-1779), the only son of John and Martha, was born in Philadelphia, educated at the Friends Public Schools (now the Penn Charter School) in Philadelphia, and in Europe where he studied medicine. Before Thomas left for Europe, he helped Benjamin Franklin organize the Library Company of Philadelphia. Thomas married Hannah Lambert in June 1738, and together they had eight children. Moving to Trenton, New Jersey, he served as commissioner of the pleas and peace and subsequently chief burgess of Trenton, and donated five hundred pounds to erect a public library. After moving back to Philadelphia, Thomas became one of the first doctors at the Pennsylvania Hospital and served as a lieutenant-colonel in the militia. He actively opposed British rule after 1765, signing agreements against both the Stamp Act and tea tax.

Thomas’s elder son, John Cadwalader, was born in Trenton on January 10, 1742 and spent his early years living there before the family returned to Philadelphia in 1750. Having attended the Academy of Philadelphia from its opening in 1751, he and his younger brother Lambert were members of the class of 1760 at the College of Philadelphia (today’s University of Pennsylvania) but apparently finished their studies in England and toured Europe afterwards. Once back in Philadelphia, they established themselves as importers of dry goods under the firm name of John and Lambert Cadwalader, and would achieve financial security and a comfortable lifestyle from their highly successful mercantile business in the largest port city in British North America.

Following John’s marriage on September 25, 1768 to wealthy Elizabeth “Betsy” Lloyd, of Wye, Maryland, the brothers closed their business. Betsy’s father, Col. Edward Lloyd, bought the couple a large townhouse and property near the corner of Second and Spruce streets, and they began to furnish it with the finest of locally-made furniture and a series of family portraits by Charles Willson Peale. Soon their redecorating and furnishing efforts turned the residence into a magnificent colonial mansion that became a luminous setting for the city’s social and financial elite.[2]

Throughout his life, Cadwalader was known as a fashionable man, buying the latest in expensive clothing and home furnishings. This engendered some criticism, particularly when, prior to the start of the War of Independence, Elizabeth ignored the boycott on British goods and continued to buy clothing, fabric, and hair accessories from London.[3] Her husband occupied a myriad of roles within Philadelphia society and pursued many pleasures. An avid fisherman and hunter, he had an affinity for horse racing and owned a variety of carriages, presiding over the Jockey Club founded in 1766, while enjoying dancing, the theater, and ice skating, as well as betting on horses and gambling at cards. Cadwalader’s memberships included St. Peter’s Church, the Gloucester Fox Hunting Company, the American Philosophical Society, and various social clubs. He was also a leader in erecting the City Tavern, a favorite meeting place of the Founding Fathers, and one of its original trustees. As his associations and activities suggest, the future Revolutionary had a taste for “the good things in life,” and these included rich food, fine claret, champagne, Madeira, and expensive clothing.[4] Indeed, the 1772 painting by Charles Willson Peale of Cadwalader, together with Elizabeth and his oldest daughter Anne, depicts a young man whose girth suggests an affinity for gastronomic delights.

When Colonel Lloyd took his son-in-law to visit George Washington’s estate at Mount Vernon in August 1769, the occasion marked the beginning of an enduring friendship between the Virginia planter and the twenty-seven-year-old Philadelphian that featured unalloyed mutual respect. When Colonel Lloyd died in January 1770, there ensued a bitter dispute between Betsy and her older brother Edward over their father’s estate of forty-three-thousand acres, one-third of which had been verbally promised to Betsy. Edward eventually capitulated to John’s arguments on behalf of his wife, but relations between them remained strained. Meanwhile, Betsy had three daughters, Anne, Elizabeth, and Maria, but died of complications eleven days after the latter’s birth, on February 15, 1776. She went to her final rest at St. Peter’s Churchyard in a lavish red cedar coffin.[5]

As merchants, John and his brother Lambert grew frustrated with the taxes imposed on the colonies by Parliament. They signed the Nonimportation Agreement of 1765 boycotting English goods and aligned themselves with the most staunch Whig faction in Philadelphia along with their first cousin John Dickinson, author of the celebrated Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania published in 1767-1768, which decried Britain’s attempts to raise revenue from its North American provinces. In 1774, Cadwalader contributed financially to the provision of food and other supplies to the inhabitants of Boston, who were distressed by Parliament’s decision to close their port in retaliation for the dumping of East India Company tea into its harbor, and the following year he rewarded a sailor who had deserted a Royal Navy ship. In addition, he served on the city’s Committee of Safety in the years leading up to the Revolution.

The Associators

The Military Association of Philadelphia, whose members were known as the Philadelphia Associators, was a private corporation first organized in 1747 by Benjamin Franklin as a voluntary fighting force at a time when Pennsylvania had no militia law. During the French and Indian War, they maintained a pair of forts and a large arsenal of artillery and small arms. By then, the Association, working through the Pennsylvania Provincial Council, had secured a legal distinction between itself and any militia that might be created by legislation.[6] Mustered anew at the onset of the Revolution, the Associators represented a cross-section of the population in Philadelphia as well as volunteers from rural Pennsylvania counties, and among their officers was Capt. Charles Willson Peale.[7] Self-trained, self-funded, and self-equipped, they came from all walks of life and represented a variety of religious sects.

After the first Continental Congress adjourned in late 1774, the Associators organized new companies on a temporary basis to train their members and prepare for self-defense. Each company elected its own officers and voted on a uniform, with its name determined by the color of the latter. John Cadwalader was chosen captain of the Philadelphia Greens. By October 1774, he had organized eighty-four men into the volunteer “Greens” or “Silk Stocking Company,” which trained at his house. After news of the fighting at Lexington and Concord arrived in April 1775, Cadwalader became colonel of the 3rd Battalion of the Philadelphia Association of Volunteers. Its members wore a brown uniform faced with white, a white vest and breeches, white stockings, half-boots, black knee garters, and a small round hat with a ribbon and sporting a tuft of deer, while carrying a large black cartridge box that bore the word “Liberty” and the number of the battalion on its flap in large white letters.[8] The Associators organized five infantry battalions and two batteries of artillery in the city, while other battalions were raised in the rural counties. The foot battalions of the Philadelphia Associators trained twice daily on the commons west of the city, led by officers who represented the elite of municipal society and politics. These included Cadwalader’s cousin and congressional delegate John Dickinson, who commanded the 1st Battalion.

Effective July 1, 1776, Pennsylvania reorganized its battalions as regiments in accordance with Continental Army standards, and the various units among the Associators were soon geographically dispersed. Cadwalader was at the head of his battalion for the reading of the Declaration of Independence in the State House yard on July 8. Along with a large number of other current or former Associators now serving with Washington’s army, he was taken prisoner when Fort Washington—under the command of Col. Robert Magaw, who led Pennsylvania’s 5th Battalion—fell to Maj. Gen. William Howe’s British and Hessian army on November 16, one of the worst defeats of the war for the Whig cause. However, Cadwalader was immediately released without parole by General Howe at the insistence of Lt. Gen. Richard Prescott— captured by the rebels during the Canadian campaign in late 1775 and exchanged for Maj. Gen. John Sullivan in September 1776—in consideration of favorable treatment he had received from Cadwalader’s father while a prisoner in Philadelphia.[9]

Ten Crucial Days

By December 1776, Cadwalader had been elected senior colonel of the Philadelphia Associators. He led over a thousand men, who mustered on December 20 and joined up with the Continental Army at Bristol in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. These troops brought no combat experience with them, but received orders to cross the Delaware River from Bristol on Christmas night to support Washington’s attack against the Hessian brigade occupying Trenton. The Associators were stymied in that undertaking by the buildup of ice on the river, which was more severe in their area, below where the main American force crossed. Even so, the latter overwhelmed the Hessian garrison in Trenton on December 26 in what Washington termed “a glorious day for our country.”[10]

Notwithstanding their victory, Washington and his generals elected to interrupt their offensive and return to Pennsylvania after their foray on the 26th, being uncertain as to the location and size of enemy forces in the area but knowing the latter had occupied nearby Princeton and Bordentown, and taking into consideration the effect that captured barrels of rum had had on many of their men while celebrating after the battle.[11] The commander-in-chief explained to congressional president John Hancock that his withdrawal was necessitated by the inability of Cadwalader’s force, along with that of Gen. James Ewing and Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam, to cross the river to support his attack because “the Quantity of Ice was so great,” without mentioning the rum found in Trenton: “I am fully confident, that could the Troops, under . . . Ewing and Cadwallader, have passed the River, I should have been able, with their Assistance, to have driven the Enemy from all their posts below Trenton. But the Numbers I had with me, being inferior to theirs below me, and a strong Battalion of Light Infantry being at Princetown above me, I thought it most prudent to return the same Evening, with the prisoners and the Artillery we had taken.”[12]

Meanwhile, Cadwalader’s men urged him to undertake an unplanned river crossing on December 27 and thereby created the catalyst for a critical sequence of events, without which Cadwalader inferred that the raid on Trenton would have limited significance. According to Maj. James Wilkinson, who was by Washington’s side during the assault on the Hessians, “The militia of Philadelphia, who showed a good countenance in the worst of times, were deeply chagrined because they could not co-operate with the continental troops on the 26th December; but being elated by our success, they became impatient for action, and crossed the Delaware near Bristol, to the number of 1,800, under [Colonel] Cadwalader, and took post at Crosswicks.”[13]

The deliberations of the commander-in-chief and his generals at their December 27 council of war were informed by the knowledge that Cadwalader’s contingent—comprising about 1,100 Philadelphia Associators and a brigade of about 350 New England Continentals under Col. Daniel Hitchcock of Rhode Island— had crossed the river to New Jersey that morning about two miles above Bristol. Writing to Washington from Burlington, the colonel reported this unexpected development in a dispatch that arrived at army headquarters just before the council of war convened, in which he advised that the enemy was fleeing and that the way was open to drive them from the western half of New Jersey:

If you should think proper to cross over, it may be easily effected at the place where we passed—A pursuit would keep up the Panic—They went off with great precipitation, & press’d all the Waggons in their reach—I am told many of them are gone to South Amboy—If we can drive them from West Jersey, the Success will raise an Army by next Spring, & establish the Credit of the Continental Money, to support it.[14]

With Cadwalader’s dispatch in hand, Washington realized the opportunity beckoned for him to follow up the attack on December 26 with a broader offensive that could change the whole dynamic of the contest. Orders were issued for the army to cross the river back to New Jersey, which it did over the next three days.

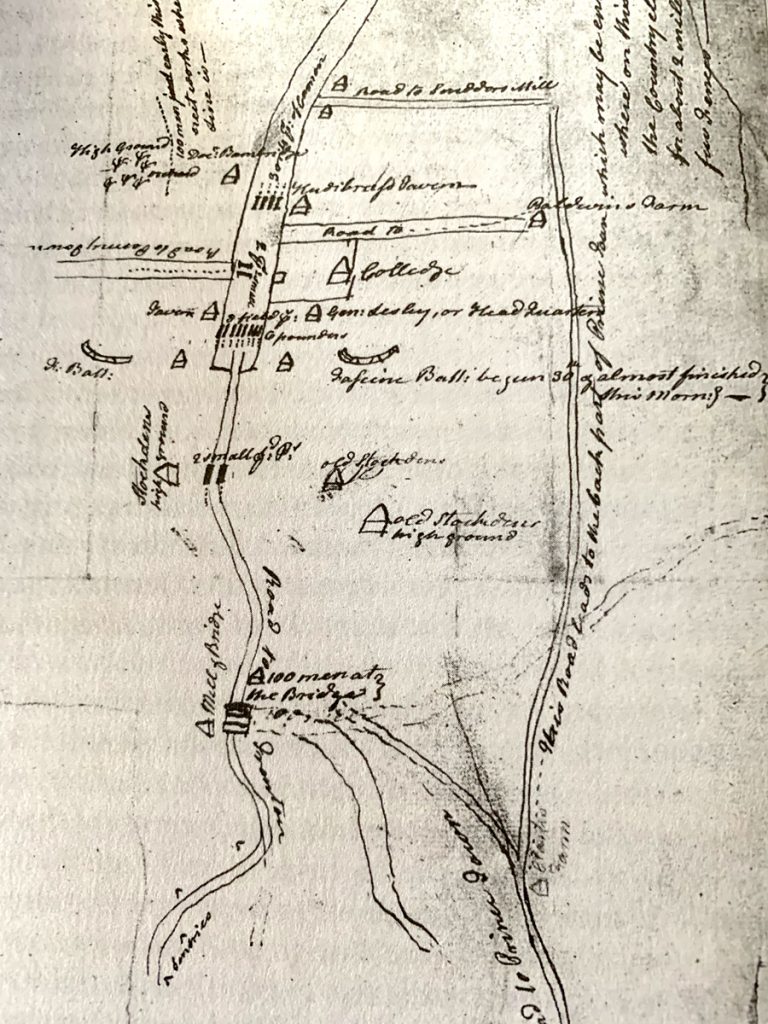

Once Washington returned to Trenton, he received intelligence from Cadwalader about the disposition of British troops gathering in Princeton. The colonel had met with a “very intelligent young Gentleman” who was detained overnight by the redcoats there but released on the morning of December 30. This youthful Patriot, whose identity is unknown, informed Cadwalader of the buildup of enemy troops and described in great detail how they were positioned. Based on this report, Cadwalader drew a crude map of the town that indicated the strengths and weaknesses of the British alignment: “I have made a rough Draught of the Road from this place; the Situation of the Cannon & Works begun & those intended this Morng.”[15] From this sketch, Washington discerned an opportunity to make a successful move against his adversary. The British in Princeton were establishing strong defenses that included artillery and breastworks to guard against a possible incursion from the north, west, or south, but they had neglected to fortify the eastern side of the town, and so it lay open to attack from that direction. Cadwalader’s map included a route from Trenton by which Washington’s army could approach Princeton from the east, where their adversary was most vulnerable.

Armed with this information, Washington held another council of war on the evening of January 1. He and his officers needed to consider how to respond to the large enemy force in Princeton, which was preparing for an all-out assault on the rebels in Trenton. It was decided to bring Cadwalader’s force—the Philadelphia Associators and the smaller brigade of New England Continentals—from their encampment at Crosswicks to Trenton in order to strengthen the army’s position in the coming battle. Cadwalader’s brigade—about 1,150 Philadelphia Associators—included three battalions of infantry, a rifle battalion, a light infantry company, a Delaware light infantry unit, some fifty Continental Marines, and an artillery company.[16] They reinforced the front line of Continental regulars when the British and Hessian forces attacked Washington’s force at the Second Battle of Trenton (or the Battle of Assunpink Creek) on January 2. The Americans held off the enemy and overnight marched to Princeton, approaching from the east in accordance with the map Cadwalader had drawn for Washington, to win the capstone victory of the “Ten Crucial Days.”

At Princeton on January 3, Cadwalader’s militia, who had had no sleep for two nights owing to their march from Crosswicks to Trenton and from there to Princeton, assisted in the final attack that drove the heavily outnumbered British from the field during a brief but fierce battle. They were part of Gen. Nathanael Greene’s division; and one of their units, the Dover Light Infantry from Kent County, Delaware, was commanded by Capt. Thomas Rodney, whose older brother Caesar Rodney had become one of Delaware’s most prominent Revolutionary War figures. Captain Rodney’s description of the action suggests its ferocity: “the enemies fire was dreadful and three balls, for they were very thick, had grazed me; one passed within my elbow nicking my great coat and . . . another carried away the inside edge of one of my shoesoles, another had nicked my hat and indeed they seemed as thick as hail.”[17] He also noted the heroics of another officer in Cadwalader’s brigade, Capt. Joseph Moulder of the Philadelphia Associators’ 2nd Company of Artillery, whose two four-pounder cannon fired deadly rounds of grapeshot into the British lines and halted their advance long enough for Washington to rally his troops—a feat memorialized in the artistry of James Peale.[18] According to Rodney, these “two pieces of artillery stood their ground and were served with great skill and bravery.”[19] Cadwalader, he observed, had led his column into battle “with the greatest bravery to within 50 yards of the enemy, but … was obliged to recoil” as his inexperienced militia bolted in the face of a fearsome onslaught by the British 17th Regiment of Foot. The colonel “fell back about 40 yards and endeavored to form the brigade, and some companies did form and gave a few vollies but the fire of the enemy was so hot, that, at the sight of the regular troops running to the rear, the militia gave way and the whole brigade broke and most of them retired to a woods about 150 yards in the rear.”[20] The rebels’ numerical superiority nonetheless enabled them to launch a successful counterattack that carried the day, and Cadwalader’s brigade, positioned in the center of the American alignment, joined in the charge. He reported that his men “bravely pushed up in the face of a heavy fire,” and as the 17th Regiment broke and ran, the merchant-turned-warrior shouted, “They fly, the day is our own.”[21]

Writing from the army’s encampment at Morristown, New Jersey, on January 15, Cadwalader advised the Pennsylvania Council of Safety that “The Militia of the City of Philadelphia and of the State of Pennsylvania have enabled General Washington to strike a blow which has greatly changed the face of our Affairs, and if they can be induced to continue a few Weeks longer there is the strongest probability that the enemy will be compelled to quit New Jersey entirely.”[22] Later that month, Washington issued discharge orders “for the present” to Cadwalader’s contingent, expressing “his Thanks to the Officers and Men of this Brigade, who nobly step’d forth at the most inclement Season of the Year, and by their Example, infused a Spirit into many of their Brethren of the province of Pennsylvania, the Effects of which the Enemy have already felt, and if properly kept up and supported must end in their total Ruin.”[23]

Afterwards

The colonel of the Philadelphia Associators declined a congressional appointment as brigadier general of the Continental Army in early 1777, notwithstanding Washington’s efforts to convince him otherwise, but did accept appointment as brigadier general of the Pennsylvania militia in August of that year and led troops in the Brandywine and Germantown engagements. Before the 1777-1778 winter encampment at Valley Forge, Cadwalader urged Washington without success to undertake another hibernal campaign rather than retiring to winter quarters, arguing that a surprise offensive would provide a much-needed morale boost to the army.[24]

During the Anglo-German occupation of Philadelphia that winter, his house on Second Street was taken over by Hessian general Wilhelm von Knyphausen, who apparently was scrupulous in his care of the residence and left its owner an inventory of its contents upon his departure.[25] Cadwalader served at the Battle of Monmouth, and on July 4, 1778, demonstrated the extent of his support for Washington’s generalship when he fought a duel with the commander-in-chief’s nemesis, the discredited former general Thomas Conway, over the latter’s alleged “cabal” among certain army officers against Washington’s leadership, inflicting a nonfatal wound to Conway’s mouth.

Cadwalader left military service in 1778 and retired to his first wife’s plantation on the banks of the Sassafras River in Kent County, Maryland, which he named Shrewsbury Farm. On January 30, 1779, the former soldier married Williamina Bond, with whom he would have three children, but only two survived their infancy. After the war, he served three terms in the Maryland House of Delegates but continued to care for the Second Street house while serving as a trustee of the Academy and College of Philadelphia. Cadwalader was only forty-four-years-old when laid low by exposure to winter’s chill while duck hunting on the Sassafras. He succumbed to pneumonia at his Kent County estate on February 10, 1786, and was buried in the Shrewsbury Church cemetery.

The Measure of the Man

John Cadwalader’s life has been described as brilliant but short.[26]According to one modern-day account, he was in his day respected as a man of energy, strong convictions, and the highest integrity.[27]Following the victory at Princeton in 1777, Joseph Reed, the Continental Army’s adjutant general and a fellow Pennsylvanian, opined that the colonel “conducted his command with great honour to himself and the Province.”[28] Washington “found him a Man of Ability, a good disciplinarian, firm in his principles, and of intrepid Bravery.”[29] Moreover, he judged his friend to be “a military genius, of a decisive and independent spirit, properly impressed with the necessity of order and discipline and of sufficient vigor to enforce it.”[30] Even a political adversary such as Thomas Paine lamented Cadwalader’s untimely death in words inscribed on the latter’s tombstone:

His early and inflexible patriotism will endear his memory to all true friends of the American Revolution. It may with strictest justice be said of him, that he possessed a heart incapable of deceiving. His manners were formed on the nicest sense of honor and the whole tenor of his life was governed by this principle. The companions of his youth were the companions of his manhood. He never lost a friend by insincerity nor made one by deception.[31]

A dozen years after Cadwalader’s passing, his younger brother Lambert conveyed a poignant tribute to his widow:

He was so perfectly free from duplicity or finesse of any kind, in fine, there was something so uncommonly excellent in the wholeof his character, that I may safely aver, tho’ I knew him most intimately from his childhood, that I have never known any one in whom there was so little to blame and so much to praise.[32]

Aside from any overall assessment of his character and ability, no estimation of Cadwalader’s value to the Revolutionary endeavor can fail to acknowledge the significance of his exploits during the “Ten Crucial Days” campaign: the dispatch to Washington on December 27, 1776 that prompted the army to cross from Pennsylvania back to New Jersey to renew its offensive; the map Cadwalader drew of Princeton for Washington that informed the army’s overnight march to Princeton on January 2-3, 1777; and his leadership at the Battle of Princeton, the climactic victory of this remarkable offensive. Put simply, Cadwalader’s contribution at a pivotal moment in the war was significant and perhaps decisive.

[1]George Washington’s Address to Congress, June 16, 1775, in George Washington, This Glorious Struggle: George Washington’s Revolutionary War Letters. Edward G. Lengel, ed. (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2007),4.

[2]Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader (Philadelphia, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964), 60.

[3]“John Cadwalader.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

[4]Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia, 2.

[6]Joseph Seymour, The Philadelphia Associators, 1747-1777 (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC, 2012), 81.

[7]Pennsylvania Archives, Sixth Series. Thomas Lynch Montgomery, ed. Vol. 1 (Harrisburg, PA: Harrisburg Publishing Company, 1906), 447.

[8]Silas Deane to Elizabeth Deane, June 3, 1775, www.silasdeaneonline.org/documents/doc12.htm.

[9]William M. Dwyer, The Day is Ours! November 1776—January 1777: An Inside View of the Battles of Trenton and Princeton (New York: The Viking Press, 1983), 117.

[10]James Wilkinson, Memoirs of My Own Times, Vol. 1 (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1816. Reprint: Sagwan Press, 2015), 131.

[11]David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 256-257.

[12]George Washington to John Hancock, December 27, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0355.

[13]Wilkinson, Memoirs of My Own Times, 182.

[14]John Cadwalader to Washington, December 27, 1776, founders.archives.gov/?q=Project%3A%22Washington%20Papers%22%20Author%3A%22Cadwalader%2C%20John%22&s=1511311111&r=5.

[15]Cadwalader to Washington, December 31, 1776, founders.archives.gov/?q=Project%3A%22Washington%20Papers%22%20Author%3A%22Cadwalader%2C%20John%22&s=1511311111&r=7.

[16]Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 409.

[17]Thomas Rodney, Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney, 1776-1777, Caesar A. Rodney, ed. (Wilmington, DE: The Historical Society of Delaware, 1888. Reprint: Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010), 35.

[18]Arthur S. Lefkowitz, Eyewitness Images from the American Revolution (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 2017), 149-151.

[19]Rodney, Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney, 35.

[21]“Extract of a letter from an officer of distinction in General Washington’s army, dated Pluckemin, Jan. 5, 1777,” in New Jersey Archives, Second Series. William S. Stryker, ed. Vol. 1 (Trenton, NJ: The John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901), 260-261.

[22]“Selections from the Military Papers of General John Cadwalader,” in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 32:1, 1908: 159.

[24]Cadwalader to Washington, December 3, 1777,founders.archives.gov/?q=Project%3A%22Washington%20Papers%22%20Author%3A%22Cadwalader%2C%20John%22&s=1511311111&r=10.

[25]Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia, 65-66.

[26]“John Cadwalader.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

[27]Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia, 2.

[28]Joseph Reed to Thomas Bradford, January 24, 1777, in William B. Reed, President Reed of Pennsylvania: A Reply to Mr. George Bancroft and Others (Philadelphia: Howard Challen, 1867), 109.

[29]Washington to Hancock, January 23, 1777,founders.archives.gov/?q=%20Author%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22%20Recipient%3A%22Hancock%2C%20John%22&s=1111311111&r=203.

[30]The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources. John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. Vol. 37 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1932), 548.

[31]“Brig. Gen. John Cadwalader, 1742-1786.”The Historical Marker Database.

[32]Lambert Cadwalader to Williamina Bond Cadwalader, August 17, 1798, in Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia, 70.

6 Comments

Great article! Did you come across any new information regarding Cadwalader being encouraged to aid Colonel Samuel Griffin in Mount Holly? Griffin wrote Cadwalader at 3am on December 23 requesting artillery and reinforcements to match those of Hessian Colonel Carl von Donop at Petticoat Bridge/Black Horse. We know Washington, thanks to Colonel Joseph Reed, was convinced to have Cadwalader’s force meet up with Griffin after crossing the river. Obviously, this did not happen because Cadwalader’s artillery did not make the crossing, and Griffin’s militia retreated to Moorestown/Haddonfield after von Donop captured Mount Holly on December 23.

Thanks, Adam. I didn’t come across anything re Griffin but then I wasn’t specifically looking for it. I obviously kept the discussion of “Ten Crucial Days” matter to a fairly general level so as to accommodate length requirements for the article.

Dear Mr. Price,

I noticed that you wrote a fine history of Welsh people in early America; Cadwalader, Lloyd, Merion and so forth are all Welsh names. So is Price. You may have an ancestor, Arthur Price, Episcopalian archbishop of Ireland (died 1752). His claim to fame is that when he died, he called his servants in to give them a farewell present, The servants were all members of the Guinness family, and what he gave them was the top-secret family recipe for stout-porter (a Welsh drink) and a bundle of money to build their famous brewery. Arthur’s recipe has helped keep the Irish economy afloat for 270 years!

John, my forbears came from Eastern Europe and I’m sure our surname was anglicized along the way. But thank you for that wonderful story.

David:

Growing up in Trenton (1950s) it was a real treat when my parents or school took us to Cadwalader Park for an outing with its deer park, monkey house (today the site of the Trenton City Museum), and a black bear den! The Park was designed by Fredrick Law Olmsted. I assumed it had been named for the Revolutionary War hero John but it was named for his father Dr. Thomas Cadwalader on the land that had been part of his large estate. I found this article about another “Trentonian” both enlightening and interesting.

Thank you for the nostalgic feedback, Joseph. I don’t have such Trenton roots myself but did work in the city for 34 years as a NJ state employee.