It has been said of Edward Hand that he was “the stuff of which the hard core” of Washington’s army was made.[1] Indeed, he may have been the most unsung Patriot military hero of the American Revolution. On the second day of 1777, Hand organized a remarkable defensive action along the road from Princeton to Trenton, New Jersey, against an Anglo-German force that heavily outnumbered his contingent. In the process, he may very well have prevented the destruction of Washington’s army and facilitated one of the most remarkable military maneuvers in history. The rebel troops halted the enemy thrust at the Battle of Assunpink Creek, or Second Battle of Trenton, and then counterattacked at Princeton in the capstone engagement of the “Ten Crucial Days” winter campaign of 1776-1777, which reversed the military momentum that had previously favored His Majesty’s forces.

Coming to America

The son of John and Dorothy Hand was the descendent of English ancestors who probably came to Ireland in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Edward was born on December 31, 1744 in Clydruff, a small village west of Dublin, but little is known about his formative years. He moved to Dublin and pursued medical studies at Trinity College while in his early twenties; however, no record exists of his having matriculated.[2] Hand enlisted as a surgeon’s mate (assistant physician) in the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment of Foot in 1767. For someone who aspired to be a physician in Ireland, this type of military service was preferred to the alternate route available for medical training, that of a five-year apprenticeship with a Dublin physician; and in the eighteenth century, Trinity graduates often occupied positions in the medical department of the British army.[3]

Hand sailed with his regiment for North America on May 19, 1767 and reached Philadelphia in July after a journey of three thousand miles across an ocean noted for its severe weather. He investigated Native American medical practices and horticulture during his frontier duty at Fort Pitt (the site of Pittsburgh today) and profited from several land transactions. These enabled the young soldier to purchase an ensign’s commission in 1772, and he became a supply officer at Fort Pitt. However, Hand eventually became disenchanted with British colonial policy, which reminded him of what the Irish viewed as England’s overbearing posture. Many of Hand’s fellow migrants from the British Isles, including the Irish and Scots-Irish, came to the New World bitterly resentful of the British government. They felt abused by edicts from London—forcing Presbyterians to pay taxes to the Church of England; excluding Presbyterians from the military, the civil service, and teaching; restricting Irish trade with other English colonies; and limiting Irish wool exports to only England or Wales—to the point where their loyalty to the Crown had lapsed. Indeed, sympathy for the Revolutionary cause among those of Irish descent was such that they, in particular the Scots-Irish, would in time constitute a significant presence in the Continental Army.[4]

Hand’s sympathy for the colonial perspective on their relations with Britain led him to sell his officer’s commission and resign from the army in 1774. He settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania—a community of about three thousand people—and turned to the practice of medicine. The newcomer met Katherine Ewing (1751-1805), whom he married in 1775, and they went on to have three daughters (only one of whom lived to adulthood) and a son. The former soldier established himself as a competent physician and industrious vestryman, and an active and responsible man of public affairs.[5] As the colonies’ dispute with Britain deepened, Hand was exposed to opinions in newspapers and various tracts in support of the Patriot cause that he could relate to his own experience. The views expressed recalled those of his fellow Anglo-Irishmen in their dispute with Parliament during Hand’s time as a student in Dublin and presumably appealed to him.

Going to War

Upon the Revolution’s outbreak, the soldier-turned-physician helped organize a local militia unit known as the Lancaster County Associators and was subsequently commissioned a lieutenant colonel in command of a rifle unit known as the 1st Pennsylvania Continental Regiment. Because of his military and medical experience, Hand was welcomed by rebel organizers when he enlisted in the cause. After Hand’s promotion to colonel, his regiment joined the newly designated Continental Army in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just outside Boston, in August 1775. Hand’s unit constituted the first detachment of soldiers to join the rebel forces from beyond the boundaries of New England; and Dr. James Thacher, a Continental Army surgeon, observed of the newcomers, “Several companies of riflemen, amounting, it is said, to more than fourteen hundred men, have arrived here from Pennsylvania and Maryland; a distance of from five hundred to seven hundred miles. They are remarkably stout and hardy men; many of them exceeding six feet in height. They are dressed in white frocks, or rifle shirts, and round hats. These men are remarkable for the accuracy of their aim; striking a mark with great certainty at two hundred yards distance. At a review, a company of them, while on a quick advance, fired their balls into objects of seven inches diameter, at the distance of two hundred and fifty yards.” Thacher reported that these sharpshooters “are now stationed on our lines, and their shot have frequently proved fatal to British officers and soldiers, who expose them selves to view, even at more than double the distance of common musket shot.”[6]

The members of Hand’s 1st Pennsylvania Regiment carried an American-made long rifle that posed a lethal threat to enemy combatants. In addition to their skilled marksmanship, these soldiers were noted for their utility, as they could be employed effectively in a variety of tactical settings: as snipers or scouts, in joint operations with regular troops, or as light infantry units were in European armies.[7] The colonel made a considerable effort to properly equip his men and instill in them a sense of esprit de corps. He ordered a silk standard or color for the regiment—made in Philadelphia and delivered to his unit by the fall of 1776—which he described as “a deep green ground, the device a tiger partly enclosed by toils, attempting the pass, defended by a hunter armed with a spear . . . on a crimson field the motto Domari nolo,” a Latin expression for refusing to yield or be subdued.[8]

Rifles were made mostly in Pennsylvania and used there and in the Chesapeake colonies by men who hunted for much of their fresh meat, but anecdotal information about this firearm’s accuracy spread far and wide. Its long barrel was etched or “rifled” with seven or eight internal grooves, unlike smooth-bore muskets, and the effect was to make the rifle accurate at a range of about two hundred and perhaps even three hundred yards, several times the range of a musket.[9] The singular nature of these instruments was recognized by the Continental Congress when it established the Continental Army in June 1775 in support of New England’s uprising against the British troops in Boston. Rifles were scarce in the colonies and, while popular in the more rural areas, largely unknown around Boston. John Adams informed his wife Abigail that the Continental Congress in which he served “is really in earnest in defending the Country. They have voted Ten Companies of Rifle Men to be sent from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, to join the Army before Boston. These are an excellent Species of Light Infantry. They use a peculiar Kind of [Firearm ca]ll’d a Rifle—it has . . . Grooves within the Barrell, and carries a Ball, with great Exactness to great Distances. They are the most accurate Marksmen in the World.”[10]

Hand’s riflemen repeatedly demonstrated what their long rifles could do in the face of superior enemy numbers. One of the more memorable displays occurred on October 12, 1776, when Maj. Gen. William Howe, the British army’s commander, landed four thousand troops at Throgs Neck above Manhattan Island in an effort to trap Washington’s force there by sealing off the main crossing to the mainland. A small detachment of Hand’s Pennsylvanians frustrated the British army and held them while another 1,500 American infantry came to their support, forcing the redcoats to abandon the effort and seek a better landing site, which they found at Pell’s Point a few days later, but too late to prevent Washington’s escape from Manhattan. Under orders from Maj. Gen. William Heath, Hand and a detachment of riflemen tore up the bridge that connected Throgs Neck to the mainland and concealed themselves behind a long pile of cord wood near its western end. According to General Heath, “Col Hand’s riflemen took up the planks of the bridge, as had been directed, and commenced a firing with their rifles.”[11] The British withdrew to the top of the nearest hill and dug in there, abandoning their objective. As historian Christopher Ward put it (dramatically, if not hyperbolically), some twenty-five American riflemen behind a wood-pile temporarily stopped the British army.[12]

By the end of 1776, Hand’s regiment had fought in nearly every important engagement since joining Washington’s army.[13] They were at the Battle of Long Island in August and endured the near-disastrous New York campaign and long retreat across New Jersey to Pennsylvania that autumn. Serving in the brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Matthias-Alexis de Roche Fermoy, a French volunteer in the patriot cause from Martinique, Hand’s soldiers consolidated with the German Continental Regiment under Col. Nicholas Haussegger, engaging the Hessian brigade at the First Battle of Trenton on December 26. Their charge toward the road leading to Princeton, northeast of the town, foiled an attempt by Col. Johann Rall’s troops to escape in that direction by skirting the Continentals’ left flank and helped seal the fate of the enemy garrison.

The Road to Assunpink Creek

Washington dispatched a body of soldiers halfway up the road to Princeton on New Year’s Eve, Hand’s thirty-second birthday, to disrupt the enemy’s anticipated advance toward Trenton. He knew he could not defeat the large force that would be marching down from Princeton under Lt. Gen. Charles Earl Cornwallis, but hoped his outnumbered troops would make the enemy pay dearly for any success they achieved. This forward deployment of rebel units included about a thousand men commanded by General Fermoy and comprised Hand’s regiment, Haussegger’s regiment, a Virginia Continental brigade, and a pair of field guns manned by the 2nd Company of the Pennsylvania State Artillery. Before sunrise on New Year’s Day 1777, the troops under Fermoy’s command occupied a position called Eight Mile Run—known as Shipetaukin Creek today—about six miles south of Nassau Hall in Princeton, which housed the College of New Jersey (after 1896, Princeton University). The rebel pickets there skirmished with British and Hessian patrols, who pushed the outnumbered Americans back but at a heavy cost.

On the morning of January 2, the lead elements of General Cornwallis’s column—the Hessian jägers (riflemen)—began to encounter scattered resistance before they had ventured far from Princeton, as small parties of rebel skirmishers began a harassing fire. Proceeding along the Princeton Road, Cornwallis’s vanguard encountered its initial resistance at Eight Mile Run, and by mid-morning, the advancing column had begun to enter into a daylong series of running battles. A mile below Maidenhead (after 1816, Lawrence Township), the Princeton Road crossed a stream called Five Mile Run, known as Little Shabakunk Creek today, where the rebels offered only token resistance. A mile beyond that was a larger waterway known as Big Shabakunk Creek. In the woods behind this larger stream, some three miles north of Trenton, the bulk of Fermoy’s men waited. As the enemy approached, General Fermoy suddenly mounted his horse without speaking a word to anyone and fled towards Trenton, thereby leaving his command to Colonel Hand as the next senior officer present. That may have been the best possible thing for the Patriot cause under the circumstances.

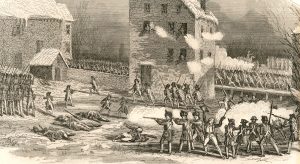

When the flank and advance guards of Cornwallis’s force approached the Big Shabakunk Creek, rebel snipers unleashed a deadly fire that broke the enemy vanguard and sent it reeling backwards into their main body, creating great confusion among these troops. Hand was “determined to waste as much time as possible for the enemy at this point.”[14] The longer it took the British commander to get to Trenton, the less time he would have to attack Washington’s army arrayed behind the Assunpink Creek before the onset of darkness limited his tactical options. Hand’s riflemen used to their advantage every kind of wooded cover as they forced Cornwallis’s main body to halt repeatedly while troops from the advance guard were deployed to drive off the unseen rebels. The soldiers under Hand’s command fell back in the face of superior numbers but fought a stubborn delaying action for most of the afternoon. They utilized every tactical means available to hinder the enemy: cannon fire, ambushes, irregular warfare, and regular infantry maneuvers.[15] Hand’s small force held off the enemy until about 3 p.m.[16] Then, facing continued heavy pressure and outnumbered by more than six to one, they began a slow withdrawal in good order toward Trenton.

At a ravine called Stockton Hollow, about half a mile north of Trenton, the rebel skirmishers made their final stand with about six hundred men. Washington, accompanied by Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene and Brig. Gen. Henry Knox, rode out from town to personally encourage the skirmishers’ continued resistance and emphasized the importance of delaying the enemy until nightfall. The commander-in-chief thanked the defenders for their efforts, “gave orders for as obstinate a stand as could be made on that ground, without hazarding the [artillery] pieces, and retired to marshal his troops for action, behind the Assunpink.”[17] When the full weight of the imperial force was brought to bear on this last point of resistance, Hand was forced to give ground to avoid being outflanked. Daylight was fading as the British and Hessians entered Trenton, and Hand’s men retreated through the town toward the Assunpink Creek bridge held by Washington’s main body.[18]

As daylight faded, the British and Hessians launched a series of probes in an effort to secure the bridge and exploit any possible weakness in Washington’s defenses; however, they were beaten back with heavy losses each time. When darkness fully descended, the two sides exchanged cannon fire to little effect for some time. Cornwallis called for reinforcements from his units in Princeton and Maidenhead and made plans to continue his assault in the morning, but the Battle of Assunpink Creek was over. His Lordship’s opportunity to continue the engagement was lost when the American army vacated its position overnight and marched around the enemy’s left flank to Princeton under the cover of darkness. There, on January 3, Hand’s riflemen assisted in overcoming an outnumbered redcoat contingent’s spirited resistance to win the final Patriot victory in their remarkable winter offensive.

On the Rise

Hand earned a series of promotions as the Revolution unfolded. He became a brigadier general in April 1777 and was assigned to command the American troops at Fort Pitt, where the threat posed by hostile tribes and the lack of support from local militia made life challenging. Hand advised Washington that “the Western Indians are united against us” and “the Militia are [called] and Promise to turn out on an Expedition that must for the Security of the Frontiers, be Carried in to the Indian Country, but they cant be induced to do duty here.”[19] The commander-in-chief replied: “I am sorry your force is not more adequate to the uses you have for it, and that such coldness appears in the neighbouring inhabitants as to preclude the assistance you had a right to expect from them.”[20] Hand subsequently reported to Washington, “When I last did myself the Honour to write to your Excy I fully Expected to be able to penetrate the Indian Country. But Alas! I was disappointed the Whole force I was Able to Collect, including Draughts from, Hampshire, Berckley, Dunmore, Loudon, Frederick & Augusta Did not exceed 800 men—I am therefore obliged to Content myself with Stationing Small Detachments on the Frontiers to prevent as Much as possible the Inroads of the Savages & rely on the Successes of Our Arms to the Northward, & Your Excellys Operations for the Rest.”[21]

Notwithstanding such difficulties, when Hand wrote his wife, Katherine, from the fort in December 1777 (the letter being addressed to “My Dearest Kitty,” the nickname he conferred upon her), the general reported: “Every thing is quiet here now. God grant it may continue so, and that I may soon have the Happiness to fold you & our Dear little Babes in my longing arms.”[22] Hand was relieved of his assignment at the fort in August 1778, in accordance with his wishes, and wrote Washington from Lancaster on the 25th “that I last Evening arrived here from Fort Pitt & in a very few days intend to wait on the board of war to give that Honorable Body a State of Affairs on the Western frontiers & settle the Accounts of that Departmt during my Command there.”[23]

In October, Washington ordered Hand to relieve Brig. Gen. John Stark on the northern frontier: “You are forthwith to proceed to Albany and take the command at that place and its dependencies—The forts on the frontiers, and all the Troops employed there will be comprehended under your general command and direction . . . . The principal objects of your attention will be the defence of the frontiers, from the depredations of the Enemy, and the annoyance of their settlements, as much as circumstances will permit; in which you will be aided by the militia of the Country.”[24] Upon arriving in Albany, Hand informed Washington that, “As the Greater part of the Troops on the Frontier are Almost naked, and the Winter Approaching, I intend Send[ing] an Officer from each Corps to head Quarters for a Supply of Cloat[h]ing for them.”[25] Hand was occupied with defending against raids by hostile Indian tribes in New York’s Mohawk Valley, a threat magnified by the Cherry Valley Massacre that November, and he led a brigade as part of the expedition under Maj. Gen. John Sullivan against the Iroquois of the Six Nations that was launched in mid-1779 at Washington’s direction.

When the campaign against the Iroquois ended, Hand returned to Lancaster for the winter but was summoned to camp at Morristown, New Jersey, by the commander-in-chief in February 1780 and served as President of court martials. He left that desk job in June to lead a contingent of five hundred men against a small army of Hessian troops advancing towards Morristown, but the enemy force aborted its effort and withdrew at news of an anticipated landing of French troops at Newport, Rhode Island. That September, Hand was ordered to serve on a board with several of the army’s highest-ranking officers in order to render a verdict on the ill-fated British Major John André, who would be hanged as a spy for assisting Benedict Arnold’s attempted surrender of the fort at West Point.

On January 8, 1781, Hand was selected as adjutant general (chief administrative officer) of the Continental Army by a vote of Congress—the last man to occupy that position during the war. He replaced Col. Alexander Scammell, who had notified Washington in November of his desire to resign the office, which prompted the commanding general to recommend Hand to the President of Congress. Washington’s letter of January 23 to Scammell’s successor broke the news: “I have the pleasure to congratulate you, on your appointment as Adjutant General to the Army. This has been announced to me two days ago officially from Congress.”[26] As adjutant general, Hand served at Washington’s side and assumed responsibility for the transmission of most general orders to the army, personnel administration, supervision of outposts, and security matters. When General Cornwallis’s besieged force capitulated to the Franco-American army at Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19, 1781, Hand accompanied General Washington and the French commander, the Comte de Rochambeau, as they rode out to one of the captured British redoubts to receive the official document of surrender.[27]

With the formal termination of hostilities by the Treaty of Paris in September 1783, Hand was made a brevet major general in recognition of his service. Four months later, Washington wrote his former comrade-in-arms to express “my entire approbation for your public conduct, particularly in the execution of the important duties of Adjutant General” and to convey “how much reason I have had to be satisfied with the great Zeal, attention, and ability manifested by you in conducting the business of your Department; and how happy I should be in oppertunities of demonstrating my sincere regard & esteem for you.” The letter included an implicit invitation to visit Washington’s Virginia home at Mount Vernon: “It is unnecessary I hope to add with what pleasure I should see you at this place.”[28]

Afterwards

Hand’s tenure as adjutant general of the army ended on November 3, 1783, and he returned to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where in 1794 he would build Rock Ford, a Georgian-style brick mansion on several hundred acres of land he had purchased. He lived there, along with his family and their servants and laborers—both enslaved and free, for the remainder of his life. Hand practiced medicine, served as a member of the Congress of Confederation (1784-1785) and the Pennsylvania Assembly (1785-1786), and subsequently as a delegate to the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention (1790). Tradition has it that he played host to President Washington when the latter visited Lancaster in 1791. At his death on September 3, 1802 at age fifty-seven (attributed to cholera morbus, a term then applied to various cholera-like symptoms), Hand was interred in St. James Episcopal Cemetery in Lancaster.

Today, the site of Edward Hand’s last home—known as Historic Rock Ford—comprises thirty-three acres at the southeastern edge of Lancaster City and is enveloped by Lancaster County Central Park. The mansion, a registered National Historic Landmark recorded in the Historic American Building Survey, is regarded as one of the most important examples of Georgian domestic architecture in Pennsylvania and the most intact building in Lancaster County from before 1800. It features an exceptional display of period furnishings and decorative arts, and is complemented by the John J. Snyder, Jr. Gallery of Early Lancaster County Decorative Arts situated in a reconstructed eighteenth-century barn.[29] In their efforts to educate the public about Hand’s life and legacy and the realities of eighteenth-century American life, the Rock Ford staff and volunteers have made this site a fitting shrine to a young nation’s spirit and enterprise.

For the past sixty years, the actions of Hand and his skirmishers against General Cornwallis’s army on the second day of 1777 have been celebrated each January in an event sponsored by Lawrence Township, New Jersey, to highlight its role (as Maidenhead) in the War of Independence. Since 1981, the part of Colonel Hand has been performed by township resident Bill Agress, joined by other re-enactors, history enthusiasts, Boy Scouts, township officials, and local residents. After a ceremony at the municipal building, they march south along Route 206 (which Hand’s men would have known as the Princeton Road, the Princeton-Trenton Road, or the Post Road) to Notre Dame High School adjacent to Shabakunk Creek,where Hand orchestrated his soldiers’ delaying action.

In final reflection, Edward Hand’s defining moment will always be that January day when his outnumbered force, and unusually mild temperatures and rain that turned the road to Trenton into a muddy morass, impeded the advance of a formidable adversary. As has been written elsewhere, one could say the weather was guided by the hand of fate and the defenders by the Hand of Pennsylvania.[30]

[1]Richard Ketchum, The Winter Soldiers (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1973), 341.

[2]Michael Williams Craig, General Edward Hand: Winter’s Doctor (Lancaster, PA: Rock Ford Plantation, 1984), 1.

[3]Richard Reuben Forry, Edward Hand: His Role in the American Revolution (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1976), 20.

[4]Michael Stephenson, Patriot Battles: How the War of Independence Was Fought (New York: Harper Perennial, 2008), 29-30.

[6]James Thacher, A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783, Describing Interesting Events and Transactions of This Period, with Numerous Historical Facts and Anecdotes, from the Original Manuscript (Boston: Richardson and Lord, 1823), 37-38.

[8]James L. Kochan and Don Troiani, Don Troiani’s Soldiers of the American Revolution (Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2007), 91-92.

[9]John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 89.

[10]John Adams to Abigail Adams, June 11-17, 1775, in Margaret A. Hogan, and C. James Taylor, eds., My Dearest Friend: Letters of Abigail and John Adams (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), 59.

[11]William Heath, Memoirs of Major-General William Heath, William Abbatt, ed. (New York: William Abbatt, 1901. Reprint: Sagwan Press, 2015), 62.

[12]Christopher L. Ward, The Delaware Continentals, 1776-1783 (Wilmington, DE: The Historical Society of Delaware, 1941), 76.

[13]Ketchum, The Winter Soldiers, 341.

[14]James Wilkinson, Memoirs of My Own Times. Vol. 1 (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1816. Reprint: Sagwan Press, 2015), 137.

[16]Henry Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, January 7, 1777, in William S. Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton(Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1898), 449.

[19]Edward Hand to George Washington, September 15, 1777,

[20]Washington to Hand, October 13, 1777, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Correspondent%3A%22Hand%2C%20Edward%22%20Correspondent%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22&s=1111311111&r=8.

[21]Hand to Washington, November 9, 1777,

[22]Hand to Katherine Ewing Hand, December 17, 1777, in the Edward Hand Papers (Collection 261), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[23]Hand to Washington, August 25, 1778, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Correspondent%3A%22Hand%2C%20Edward%22%20Correspondent%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22&s=1111311111&r=10.

[24]Washington to Hand, October 19, 1778, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Correspondent%3A%22Hand%2C%20Edward%22%20Correspondent%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22&s=1111311111&r=13.

[25]Hand to Washington, October 29, 1778, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Correspondent%3A%22Hand%2C%20Edward%22%20Correspondent%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22&s=1111311111&r=16.

[26]Washington to Hand, January 23, 1781, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Correspondent%3A%22Hand%2C%20Edward%22%20Correspondent%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22&s=1111311111&r=65.

[27]Craig, General Edward Hand, 95.

[28]Washington to Hand, January 14, 1784, https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Correspondent%3A%22Hand%2C%20Edward%22%20Correspondent%3A%22Washington%2C%20George%22&s=1111311111&r=87.

[29]https://historicrockford.org.

[30]David Price, The Road to Assunpink Creek: Liberty’s Desperate Hour and the Ten Crucial Days of the American Revolution (Lawrenceville, NJ: Knox Press, 2019), 194.

9 Comments

Thank you for this excellent, thorough, and most informative biographical sketch of Edward Hand. Your mention of the unusual regimental standard really caught my attention, and I was quite interested to learn that it survives to this day, due to sophisticated and complex preservation efforts: http://statemuseumpa.org/pennsylvania-icons-revolutionary-war-flag/

I’m glad you enjoyed the article. Thank you for sharing the information about the regimental standard.

Excellent article on a great patriot. I assume Charles Scott of the 5th Va Regt was leading Adam Stephen’s Va Brigade in his absence. Must have been the addition of these 500 hundred or so that brought Hand’s strength to 1,000. I think we can say Fermoy’s sudden departure contributed to a more favorable result.

Thank you for an excellent article shedding some light on a great American hero!

Having visited his home in Lancaster several times, it is well worth the visit.

David, I thoroughly enjoyed your finely written and well-researched feature on General Edward Hand. Articles like yours shed light on the second tier of generals that deserve attention for their important contributions. That is why I wrote my feature for JAR several years ago on Gen. Jedediah Huntington of Connecticut, which I hope you’ll read and comment on. One fun connection between Generals Hand and Huntington is that they helped co-found the Society of the Cincinnati in the late spring of 1783. I have the source material if you are interested. Again, congratulations on a fine piece added to our historical record. Cheers, Damien

Damien, thanks for your comments and for alerting me to your fine article. I think Huntington & Hand must have also served together on the board that determined Major Andre’s fate. Since you’ve written so much about Connecticut in the Revolution, you’ll be pleased to know that I’m highlighting the role of Thomas Knowlton in my next book – “The Battle of Harlem Heights, 1776” – which will be part of Westholme’s “Small Battles” series. I also wrote a JAR article about him last year (“Thomas Knowlton’s Revolution”). There’s more info. about the upcoming book on my website at dpauthor.com. Best wishes.

Yes indeed, David, Generals Hand and Huntington both served on the Andre trial. You may have also seen and read my feature on Washington’s Councils of War, which of course includes Hand among other generals. Another interesting contribution of Hand was in the federal period, when his expertise with rifles led to his procuring rifles for the small, fledgling U.S. Army in the 1790s. Thanks for your heads up about your Knowlton feature and your book, too!

Mr. Price, you can find additional information in the Pennsylvania Archives; 2nd Series, Volume X, P 4, about Mr. Hand.

The archives can be accessed on Wikipedia.

Go to Wikipedia, in upper right corner, enter “Pennsylvania Archives” and press enter. The PA Archives will come up and you can chose the series and volume you want.

Thank you for that information.