The last level of British authority at the colony level was the colonial governors. They came in various forms, military and civil, appointed and proprietary, and occasionally elected by the colonists. As British authority started to break down, the colonial governors were some of the most prominent people to be chased from their respective colonies. Did they go quietly, or did they drag their heels all the way? Where did they go and where did they end up? Did they plot their return, stubbornly clinging to power, or did they fade quietly into the sunset?

It’s worth revisiting how each colonial governor reacted to the fast-changing conditions of the 1770s and what eventually happened to them, so I decided to survey all twelve (Delaware was administered by the colonial governors of Pennsylvania as the Lower Counties on Delaware). Here is a capsule story for each:

Connecticut: Jonathan Trumbull

Trumbull was unique among the colonial governors in that he supported the revolution, making him the last governor of the colony and the first governor of the state. He was also one of two that were elected, Joseph Wanton of Rhode Island being the other. On October 10, 1776, the Connecticut General Assembly approved the Declaration of Independence but resolved that civil government would otherwise continue as established under its charter. During the revolution Trumbull assumed much more extensive powers than the state charter outlined for the governor due to his role in the war. Connecticut was a significant supplier to the war effort, supplying an estimated 60 percent of the manpower, food, clothing, and munitions for the Continental Army.

As the war neared its close, Trumbull experienced declining popularity due to rumors of war profiteering (including possibly trading with the British) and statements he made that demonstrated a less than strong commitment to revolutionary principles. When he decided not to run in 1784, he had failed to attain 50 percent support in three of his last four elections. Completing the precipitous decline, he died of a stroke at his home in Lebanon, Connecticut on August 17, 1785. Despite events in the latter part of his life, Trumbull was a revered figure in death, with many places in Connecticut named in his honor.[1]

Georgia: Sir James Wright

Wright owned over 500 slaves and was well on his way to becoming the state’s largest and wealthiest landholder when the Revolution arrived.[2] Georgia was an exception among the original thirteen colonies, remaining in the British camp longer than the others. It was the only colony to actually sell stamps under the Stamp Act and did not send delegates to the First Continental Congress. The momentum of the revolution became too strong in 1776 and, after having briefly been imprisoned in his home by rebel forces, Wright escaped and sought refuge on board the British warship Scarborough. When further attempts to regain control of the state proved unavailing, he returned to England.

Wright was not finished, using his time in England to petition for a full-scale invasion of Georgia. This eventually came, coinciding with the British southern strategy in 1778 that regained Savannah. Wright was able to re-assume his governorship, returning in July 1779, the only colonial governor to return to his post. He helped repulse several attempts by the rebels to recapture Savannah, including one joint Franco-American attack.

When the war was finally lost, he reluctantly withdrew for good in July 1782, retiring to England. He died on November 20, 1785 and is interred in Westminster Abbey.[3]

Maryland: Sir Robert Eden

Eden may have been the only colonial governor given the opportunity to leave on his own, and he took it. Eden’s power base came from his marriage to Caroline Calvert, the sister of Lord Baltimore, in 1763. Three years later he was governor of Maryland. Although sympathetic to some of the colonists’ complaints, Eden was strongly against armed opposition to the Crown. In 1774 he prorogued the Maryland Assembly and was largely powerless after that. Despite this, he remained in office into 1776.

Though pressed by the Continental Congress to arrest and detain Eden, the Maryland Council of Safety asked him to step down as governor and did not forcibly eject him, opting instead for a largely non-contentious transfer of power which occurred in June 1776. In August 1783 Eden returned to Maryland to recover some property (his lavish lifestyle and gambling problems put him in dire financial straits on both sides of the Atlantic), and he died there in 1784 at age forty-two. He is buried in Annapolis.[4]

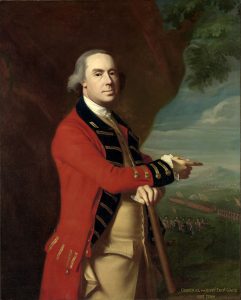

Massachusetts: Thomas Gage

Though Thomas Hutchinson took much of the wrath as royal governor, Gage took over just as events reached a boiling point. Gage was commander in chief of the British forces in America from 1763 to 1772. He left for England in 1773 to take care of personal business and reluctantly returned in April 1774 after being named governor, replacing Hutchinson. After the humiliating defeat of Lexington and Concord and the pyrrhic victory at Bunker Hill, Gage was recalled to England by King George in 1775, and his actions received severe criticism.

For a time Gage had no role in the army other than the colonelcy of a regiment. In 1781 he was assigned to command forces guarding against a potential French invasion of Great Britain, which never came. Gage died on the Isle of Portland on April 2, 1787. [5]

New Hampshire: John Wentworth

Wentworth was a classmate of John Adams at Harvard University. He was well-liked but the rising revolutionary tide ultimately undermined his authority and power. His credibility suffered significantly when he hired New Hampshire carpenters late in 1774 to build barracks to house the overflow of British soldiers from Boston. His attempt to pack the state assembly with friends in 1775 was met one morning with a cannon ominously aimed at his front door. Wentworth and his family realized their tenuous situation and fled to Fort William and Mary, in New Castle, New Hampshire, under the guns of the British warship Scarborough at Portsmouth. When Scarborough went to Boston, the Wentworths went with it. The former royal governor stayed on only to flee to Halifax when the British abandoned Boston in March 1776, then sailed alone for England in 1778.

Wentworth returned to North America in 1783 and held the position of Surveyor of the King’s Woods in Nova Scotia. He and his wife returned to England in 1791, soon to learn that the military governor of Nova Scotia had died. They returned to Nova Scotia in 1792 as John was named the first civilian governor. Wentworth was knighted and awarded a Baronetcy in 1795. He was recalled to England in 1808, but when debt collectors caught up to him, he fled back to Nova Scotia in 1812 under an assumed name to secure the property needed to get him out of debt.[6] While he was gone, his wife Frances died at Sunninghill, Berkshire, England, February 14, 1813, at age sixty-eight. With no reason to return to England, John stayed in Canada where he died on April 8, 1820, at age eighty-four the longest and last surviving colonial governor.[7]

New Jersey: William Franklin

William Franklin is probably the most famous of the colonial governors. The illegitimate son of Benjamin Franklin, the two went in decidedly different directions when it came time to be counted for the Revolution, and their famous split was both bitter and lifelong. Franklin the younger was originally appointed as governor by the King in 1762. In his “Two Roads” speech to the New Jersey Assembly, Franklin drew a harsh dichotomy between “one evidently leading to Peace, Happiness, and a Restoration of the publick Tranquility the other inevitably conducting you to Anarchy, Misery, and all the Horrors of a Civil War.”[8]

The Continental Congress declared William Franklin “a virulent enemy to the people of this country and a person who may prove dangerous”, and exiled William from New Jersey. He was sent to solitary confinement in Litchfield, Connecticut after violating terms of his house arrest. He unsuccessfully petitioned Governor Trumbull for mercy and, when he found out his wife was gravely ill, wrote to Washington for permission to see her. Washington would not countermand an order of the Continental Congress, and Franklin’s wife died while he remained imprisoned. Finally, suffering from ill health himself, he was exchanged in 1778 and went to New York and on to England.

The rest of William’s life was pretty much defined by the delicate dance between father and son, seeing who would forgive first. Neither ever did, or more accurately Benjamin didn’t. Ironically, William never saw himself as his father’s enemy by his actions towards his father. Throughout the war, he continually inquired about his father’s well-being, although Benjamin never returned the favor. William’s letters were always dotted with flattering references to Benjamin Franklin, and he refused to criticize his father, even when friends invited him to do so. He was almost obsessed with efforts to remind himself of his once-proud connection to the great Benjamin Franklin. If he was, as Benjamin Franklin insisted, his father’s enemy, he was an unnatural—and loyal—enemy, indeed.[9]

William died in 1813 and was buried in London’s St. Pancras Old Church yard. The location of his grave has, over the years, been lost.[10]

New York: Andrew Elliot

If things had gone as they did in the other states, we’d be talking here about William Tryon and his exploits in the early-mid 1770s, including maybe his role in a failed plot to kidnap or assassinate Washington. However, the British took New York City and didn’t relinquish it until the end of the war. This means another man, Andrew Elliot, served as the accidental and last royal governor of New York for a brief term of April to November 1783. In between Tryon and Elliot, James Robertson was the military governor, but despite Robertson’s much longer tenure, it was Elliot who served the office last.

Within two years of the British conquest of Manhattan, Elliot became the de facto head of the occupation regime’s civil government, wielding more power than any other colonial official before him.[11] His positions included customs collector and receiver of quitrents, superintendent of imports and exports and of the police, lieutenant-governor, and finally, on April 27, 1783, acting governor.

In 1783, Elliot and Sir Guy Carleton, the new British commander in chief for the colonies, ventured to Tappan, New York to meet with General Washington and future New York Governor George Clinton. They discussed prisoner exchanges and the evacuation of New York. After the war, Elliot used connections established during the war to weather his losses in property in New York and Philadelphia and obtain a comfortable rural retirement in Scotland, where he lived until his death in 1797.[12]

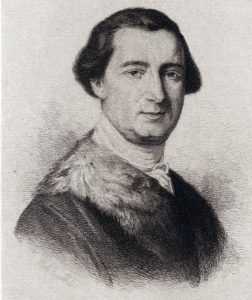

North Carolina: Josiah Martin

Martin was appointed governor by the Crown in 1771. Once the war started, things got hot fast for Martin. His home was attacked by Whig mobs in 1775, causing him to dispatch his family to New York while he took refuge aboard the British warship Cruizer on the Cape Fear River.

When the British opted for their Southern Strategy, attempts were made to restore his administration, much as had been done with Sir James Wright in Georgia. These attempts fell short. Martin, now ill and fatigued, had seen and had enough, leaving first for Long Island (where he had a home) before finally returning to England. He died in April 1786 in London and is buried there at St. George’s Hanover Square Church.[13]

Pennsylvania: John Penn

John Penn was the grandson of original Pennsylvania proprietor William Penn. Having bitterly contended over the years with Benjamin Franklin about the proprietary structure and the tax status of the Penns, the coming of the Revolution only created more problems for Penn. He declined to convene the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1774 in order to avoid the election of delegates to the First Continental Congress. The Patriots responded by taking control of the assembly in 1775 and its last session adjourned on September 26, 1776.

Concurrent with the Declaration of Independence, Pennsylvania created the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, replacing Penn’s government completely. Penn was left to remain neutral in the conflict with the hopes that the colonies might become reconciled again with the King. In 1777, as the war turned to Philadelphia, the Patriots decided to put Penn under house arrest, exiling him to Fredericksburg, Virginia. When the British abandoned Philadelphia in early 1778 and the Patriots returned, loyalty oaths were required. Penn obliged in order to protect, unsuccessfully, his lands and investments. The Penn estate was by far the largest forfeited in America. Lobbying the British government for more compensation for their lost lands was largely unavailing, and John Penn lived the rest of his life with his family quietly at Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, dying in 1795.[14]

Rhode Island: Joseph Wanton

Some might claim Nicholas Cooke, Wanton’s successor, as Rhode Island’s last colonial governor, but given his presiding over the May 4, 1776 passage of the state’s own Declaration of Independence, I am going to say Wanton is the man. Originally becoming governor in 1769, Wanton was re-elected for the sixth time in 1775. As the war got underway, the General Assembly in Rhode Island looked to do its part by raising an army of 1,500 men. Wanton refused to comply and would not commission officers. He also hesitated in taking the oath of office, and the Assembly refused to seat him, eventually formally voiding his election and replacing him with Cooke.

Interestingly, Wanton was not overtly loyalist, he simply did not see war with Great Britain as a good move for either the colony or the country. After his removal as governor, he retired to his home in Newport. As a Quaker, Wanton took a strictly impartial stance, giving aid neither to the British nor the Patriots. As a result, future governments did nothing to threaten him or confiscate any of his property. Wanton died in 1780 and was buried in the Clinton Burying Ground in Newport.[15]

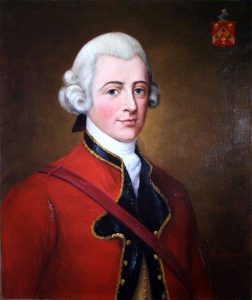

South Carolina: Lord William Campbell

South Carolina had a distinctive split between the aristocratic Low Country people and the backwoods Up Country population, the latter being more inclined towards loyalty to the Crown. When the patriots in the state attempted to form a new Congress in 1775, Campbell bombarded the Up Country with pamphlets disparaging it. Numerous patriot threats and attacks, including one on the house of Henry Laurens, soon convinced Campbell that he was not safe.

He soon departed for the safer environs of the British warship Tamar located off Charleston. In June 1776 he participated in the British attack on Sullivan’s Island, a small spit of land off Charleston. Campbell was injured aboard the ship Bristol. He never fully recovered and died of his wounds two years later at the age of forty-eight.[16]

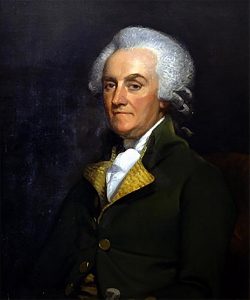

Virginia: John Murray, Earl of Dunmore

The Earl of Dunmore was one of the more controversial governors, in a colony very active in the Revolution. Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” was a challenge to Dunmore.[17] Beginning in the early 1770s, tension built between Dunmore and the House of Burgesses due to the latter’s revolutionary sentiments. He dissolved the Burgesses in 1772, 1773, and 1774, the multiple dissolutions because the Burgesses continued to meet extra-legally. Dunmore tried, with limited success, to gain control over the colony’s military supplies. Eventually, like so many others of his counterparts, he was forced to take refuge offshore, in this case aboard the British warship Foweyin the James River, from which he declared martial law and directed raids on plantations.

Dunmore’s real dagger for the Patriots was his Proclamation, which offered freedom to any enslaved person willing to fight on the British side. On New Year’s Day 1776 Dunmore issued an order to burn the waterfront buildings in Norfolk from which Patriots were firing on his ship, a move that led to the destruction of the entire town by American troops. Soon Dunmore beat a hasty retreat to New York and then on to England in July 1776, once it appeared all was lost for him in Virginia. He continued to draw his royal governor’s pay until the end of the war in 1783.

Dunmore was governor of the Bahamas from 1787 to 1796, and in the process made it one of the destinations for displaced loyalists. He died on February 25, 1809, in Ramsgate, Kent.[18]

[1]Jonathan Trumbull, Museum of Connecticut History, Jonathan Trumbull (museumofcthistory.org).

[2]Greg Brooking, “Sir James Wright and Jenny his ‘free black servant’,” earlyamericanists.com/2014/01/28/sir-james-wright-and-jenny-his-free-black-servant/.

[3]Lorenzo Sabine, Sir James Wright, The American Loyalists (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1847), 726-727. For more on Wright, see Greg Brooking, “‘My Zeal for the Real Happiness of both Great Britain and the Colonies’: The Conflicting Imperial Career of Sir James Wright,” PhD diss., Georgia State University, 2013.

[4]“Robert Eden,” msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/000300/000391/html/391bio.html.

[5]“Thomas Gage,” www.encyclopedia.com/people/history/british-and-irish-history-biographies/thomas-gage.

[6]Judith Fingard, “Wentworth, Sir John,”www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wentworth_john_1737_1820_5E.html.

[7]“Governor John Wentworth,” www.seacoastnh.com/governor-john-wentworth/. For more on Wentworth see Peter E. Randall, ed., “NH: Years of Revolution”, New Hampshire Profiles, 1976.

[8]William Franklin’s Speech to the New Jersey Assembly, January 13, 1775, www.kean.edu/~NJHPP/americanRevolution/theTwoGovernors/documents/theTwoGovernorsDoc2.pdf.

[9]Sheila L. Skemp, “Benjamin Franklin, Patriot, and William Franklin, Loyalist,” Pennsylvania History Vol. 65, No. 1 (Winter 1998), 44.

[10]“William Franklin,” William Franklin | American Battlefield Trust (battlefields.org). For more on the Franklins and their relationship, see Sheila Skemp, Benjamin and William Franklin: Father and Son, Patriot and Loyalist (Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin’s Press, 1994).

[11]Donald F. Johnson, Occupied America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 97.

[12]“Andrew Elliot,” archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/andrew-elliot.

[13]“Martin, Josiah,” www.ncpedia.org/biography/martin-josiah.

[14]Sabine, Sir James Wright, 514-517.

[15]Thomas Williams Bicknell, The History of the State of Rhode Island – Volume III (New York: The American Historical Society Inc., 1920), 1093-1095.

[16]“Campbell, Lord William,” www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/campbell-lord-william.

[17]“Lord Dunmore,” www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/lord-dunmore.

[18]“John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore,” www.encyclopedia.com/history/educational-magazines/lord-dunmore.

One thought on “The Last Royal Governors of the American Colonies”

The connection between Governor Dunmore and the burning of Norfolk, Virginia is now known to have been more tenuous. Patriots had been firing for weeks on Dunmore’s ship in the middle of the night and then galloping away with the small cannons, so he announced that if the mayor did not prevent the firing he might return fire. He did return fire, about ten shots with his tiny cannons with bore about the size of a golf-ball, and the Patriots took that as the signal to burn Norfolk to the ground — and blame it on Dunmore. Every single building in Norfolk was destroyed except for the elegant brick hospital. It was not until the Bicentennial that scholars were able to uncover what had really happened.