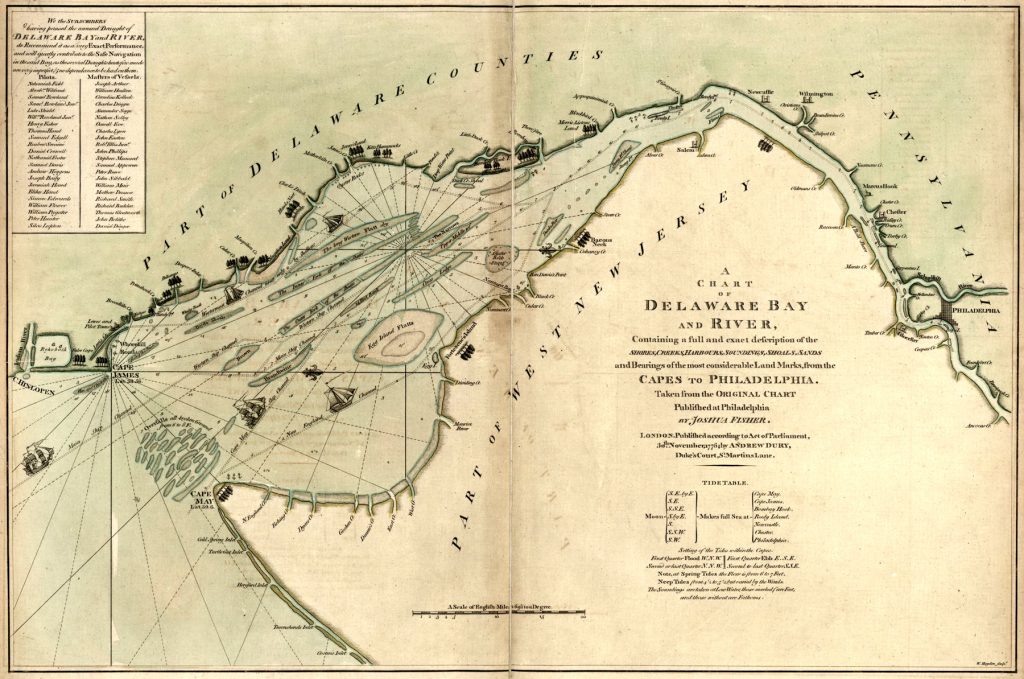

On June 30, 1775, the Pennsylvania General Assembly recognized the direct threat Philadelphia faced should the Royal Navy take control of the Delaware and acted to further strengthen their defenses with the creation of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety. By September this new committee implemented preliminary resolutions to inhibit the Royal Navy’s ability to reach Philadelphia while preparing for the inevitable arrival of enemy naval forces on the Delaware Bay. All Pilots of the Bay and River Delaware were ordered by the committee on September 16, to “lay up their Boats on or before the 20th day of September inst. and cautiously avoid going on any navigable water or other place on Land or Water, where they may probably fall within the Power of British Men of War, armed Vessells or Boats.”[1] The difficult navigability of the Delaware served as a natural defense for Philadelphia and without the aid of local pilots, the Royal Navy would face grave difficulties in reaching the city. Lewistown, Delaware, sitting prominently at the mouth of the Delaware River and Bay, would serve a critical role in relaying the actions of enemy vessels on the Delaware directly to the Committee of Safety in Philadelphia.

The Alarm Committee, a sub-committee of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, was created on March 9, 1776 and included three seasoned captains: William Richards, Nathaniel Falconer, and Thomas Reed. These men were “fully impower’d to fix signals for giving alarm at Cape Henlopen, and at such other places on either side of the Bay and River Delaware, as they shall judge proper, and also to engage for Men and Horses to be in readiness to convey intelligence by Land.”[2] To effectively create this system, they relied upon the services of Pilot of the Bay and River Delaware and resident of Lewistown, Henry Fisher. Fisher was tasked with serving as the committee’s eyes and ears on the Delaware and to give “advice to this Board [Committee of Safety] of every British Man-of-War or armed Vessel that may arrive at the Capes of Delaware.”[3] Fisher’s orders from the committee gave him the authority to supervise and oversee the pilots of the lower Delaware, take necessary action to ensure they avoided capture, and to efficiently communicate all British actions on the Delaware to the committee.

On March 20, Captain Falconer’s application for £300 for “fixing Signals, such Guns, Ammunition, and Implements” was approved by the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety. [4] Under the direction of the committee, a series of thirteen coastal alarm posts were established between Lewistown and Philadelphia. Each post was fitted out with a smaller signal gun often accompanied by a small vessel or pilot boat, as well as a crude cabin for the sentries operating the post.[5] These thirteen posts included Cape Henlopen, Mushmellon (Mispillion Creek), Motherkill (Murderkill River), Bombay Hook, Step Water Point (Port Penn), Long Point, Dalby Point, Chester, Thompson Point, Billingsport, Gloucester, Market Street Wharf, and Point no Point (Frankford Creek).[6] A handful of pilots, now unable to ply their trade on the river, were employed with their boats at a number of posts, including Henry Fisher at Lewistown, George Jackson at Mispillion, as well as Samuel Edwards and John Marshall at the Murderkill.[7] In addition to each alarm post, a series of stations for express riders was established at Cedar Creek, Dover, Cantwell’s Bridge, Wilmington, and Chester. These alarm posts and express stations would work in coordination to relay any danger to one another and ultimately north to Philadelphia. “Discovering any Ship or Vessell standing in for the Land,” the keeper of the lighthouse at Cape Henlopen would light an agreed-upon signal immediately notifying Lewistown.[8] Beginning with Henry Fisher’s personal pilot boat, stationed at the mouth of Lewes Creek, each station would fire their signal gun and riders would be dispatched to promptly relay the alarm. This express, with riders carrying urgent messages, had the ability to relay a message from Lewistown to Philadelphia in twenty-one hours.[9]

Throughout the remainder of 1775 and into early 1776, the committee continued to take additional action, preparing for the Royal Navy’s impending arrival. In September 1775, the committee loaned six six-pound cannons to Lewistown as well as 200 pounds of gun powder, 600 pounds of lead, 20 rounds of grape shot and 12 round cannonballs. Additionally, the buoys on the river and bay that marked shoals and channels were removed, thus making navigation of the river increasingly difficult.[10] In November 1775, the committee wrote to Delaware River and Bay Pilot James Maul, instructing him to be stationed “near the mouth of the Delaware” and to “take on board your Pilot Boat four Persons besides yourself, three of whom to be Men, and such as you have Reason to believe will be sober and attentive to their Duty, and proceed to the Thoroughfare below Reedy Island, which is to be your general Station, with liberty sometimes to run down the Thrum-Cap Road.”[11] Sighting any British vessels, Maul was also advised by Fisher to immediately notify the commander in New Castle, Delaware, with the message then carried to Fort Island (Fort Mifflin) and the Committee of Safety. Even after Maul was relieved of his station in March 1776, the committee “desired to have his place supplied immediately, by another pilot of sufficient ability and Industry,” thus highlighting the importance of a sentry on the water.[12]

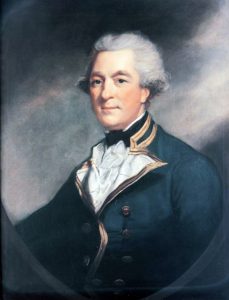

While Fisher and the Committee of Safety worked towards strengthening the defenses of the Delaware, the British Admiralty began to deploy vessels to the Delaware Bay. British Vice Admiral Samuel Graves wrote to Capt. Andrew Snape Hamond of the Royal Navy ship Roebuck on January 26, 1776 with orders to sail to Virginia and take command of British ships and vessels on that station. Hamond was also tasked “to endeavor to Guard the Entrance of the River Delaware by Cruizers until the Navigation is Open, and His Majesty’s Ships can Anchor in the River.” Additionally, he was to “prevent any Supplies getting to the Rebels, to annoy them by all means in your Power,” and “to procure as many good Pilots as you can for the River and the Coast of the twelve United Colonies, and bear them on a Supernumerary List for Victuals only to be supplied occasionally to the Kings Ships.”[13]

In early March of 1776 Hamond wrote to British Vice-Admiral Molyneux Shuldham, expressing that he had “not yet been able to procure a Single Pilot for Philadelphia,”[14] although at this time he had acquired a number of skilled pilots for both Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay. In that same correspondence, Hamond wrote:“I confess, however that, I am of opinion as the River is now become rather formidable, a much larger force is necessary for that service, than I am able to carry thither from hence.”[15] He then suggested, “Not less than three or four Ships of good force with a small one to cruise off Capes can promise much success in opening the passage up to narrow a River which the Rebels have employed their whole art and industry for this year past to block up.”[16] Lacking the reinforcements requested, Roebuck set sail from Hampton Roads, Virginia, and arrived on the Delaware Bay on March 25, 1776.

Cruising the shoal-laden Delaware without a local pilot at the helm was a dangerous undertaking. At the time of her arrival on the Delaware, Roebuck acquired five pilots, now listed on her muster book. These included Virginia pilots Daniel Cook and David Chambers, Chesapeake Bay pilots Robert Stevens and Robert Lightbody, and most importantly, James Jones, “Pilot for the River Delaware.”[17] Even with a skilled local pilot at the helm, Roebuck ran ashore on the beach, yet was able to back off without damage.

In Lewistown, Fisher wrote to the Committee of Safety, urgently notifying them of the recent arrival on the Bay. At this point, Fisher was unsure of Roebuck’s intentions, yet assured the committee that those in Lewistown “shall do our outmost to prevent their getting any Pilot or Pilots from this place.”[18] The following morning, Fisher’s letter was read to the Committee of Safety during a special meeting at the London Coffee House in Philadelphia. In response, the committee proposed naval action to parry the British advances. Commodore Andrew Caldwell was summoned before the committee and ordered to “send four of the armed Boats, well filled & manned, immediately down the River, as far, if necessary, as Reedy Island.” The officers of these vessels were given the orders to “exert their utmost Endeavours to take or destroy all such Vessels of the Enemy as they shall find in the River Delaware.”[19] While the Committee of Safety enacted a naval solution for the protection of Philadelphia, the situation less than one hundred miles south on the Delaware Bay was escalating.

In the early morning of March 26, Roebuck, at anchor in Old Hoar Kill Road in the Delaware, spotted “a Sail Standing up the Bay” and saw that a “pilot boat came out of Lewes Town in order to give intelligence at Philadelphia.”[20] Captain Hammond immediately “sent the Boats manned and Armed after her.” Roebuck’s crew “had no difficulty in coming up with her,”[21] and returned that evening with a prize. This captured pilot boat was Henry Fisher’s personal vessel that had been stationed as the alarm boat at the mouth of Lewes Creek. Although Roebuck’s crew captured Fisher’s vessel, Roebuck failed to take any pilots from this prize. The crew of the pilot boat managed to row ashore at the Broadkill (Creek) in their skiff, leaving Fisher’s vessel for the taking.[22] The following day, March 27, Fisher’s pilot schooner was armed and manned with seamen from Roebuck and put under the command of Lt. George Ball.[23]

Hamond followed his orders to “annoy them by all means in your Power,” as Roebuck continued to pluck vessels off the Bay as prizes. In the captured pilot boat, Lieutenant Ball captured the Dove, of Plymouth, Massachusetts, which was heading for Philadelphia on March 28.[24] Additionally, the Maria, a tender of Roebuck, gave chase to a sloop anchored off the Hens and Chickens’ Shoals and returned with the Dolphin as her prize in the early hours of March 29.[25]

Henry Fisher wrote to the Committee of Safety on April 1, providing a heavily detailed summary of the activity that occurred in Lewistown and on the Delaware Bay the previous week. Unfortunately, the alarm system that had been implemented to notify Philadelphia of any British vessels failed to work. In his correspondence, Fisher shared that:

The Pilot Boat stationed near Lewes Creek’s mouth did not discover the signal at the Light House, nor See the Ship that evening as it was near dark before she came to the Pitch of the Cape, and when the Alarm Guns were fired the People on Board the Boat, altho’ they heard them very plain, imagined as they said that we were cleaning the Guns with a proof charge.[26]

Despite having lost his pilot boat on March 26, Fisher shared the details of its re-capture on March 29. The Royal Navy helmsman of the pilot boat inadvertently fell asleep and the vessel drifted ashore at Cape Henlopen. Roebuck’s Lieutenant Ball and all three of his seamen were then taken prisoner by Fisher’s men, with the pilot boat “stripped of every thing of value” including “Ten Musquets and five Pilstels which had been hove over the side where the boat lies.” [27] On March 29, vessels dispatched by the Committee of Safety began to further deter British naval actions. Per Fisher’s report, the Sloop Hornet appeared near Indian River in addition to the Brig Lexington that came down under Cape May.[28]

Following the arrival of Roebuck, Fisher kept sentries on guard at Cape Henlopen, Lewistown, and Pilot Town. Additionally, the militia with “several companies from all part of the county who live within twenty or five & twenty miles of Lewes” now began to arrive for the defense of Lewistown. Despite the turmoil of the preceding week, Fisher assuredly stated that those defending Lewistown “seemed all quite unanimous and hearty in the Cause determined to defend their Country.”[29] Roebuck’s early transgressions on the Delaware Bay prompted additional action from the Committee of Safety and identified their shortcomings in defending the lower Delaware. The men captured from Roebuck were interrogated in Lewistown by Henry Fisher, who shared their warning with the Committee of Safety on April 2: “You may dayly expect several large ships, therefore I hope that you may be upon your Guard as from what I can learn they are to come up your river.”[30]

Fisher’s correspondence further solidified the committee’s concern that the Delaware Bay remained vulnerable and that a stronger maritime presence was necessary. William Price, Philadelphia mariner and late lieutenant of the ship of war Britania during the Seven Years War, also petitioned the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, on April 1, and recommended a resolution towards securing the lower Delaware. Price proposed the Committee fit out “two good sailing sloops or schooners” to “cruise in the bay and along the shore within and about the shoals, as far North as Egg harbour and as far South as the Capes of Virginia, by which means they will be sufficient to take and destroy separately whatever tenders they have or may fit out, and protect the Vessels going out or coming into this river.”[31]

Finally, on April 3, the Committee of Safety proposed fitting out “two or more fast sailing vessels of small draft of water were properly equipt, they might protect the trade of this and neighboring colonies in the Bay of Delaware, now infested with Tenders and small armed vessels of the Enemy.”[32] Later that day, the proposal was approved and the Marine Committee was “directed and empowred to fit out, with all expedition, two armed cutters, for the service of the continent.” [33]

The committee also agreed to send military reinforcements to Lewistown on April 3, ordering the “commander of the battalion raised in Delaware government, be directed to send two companies of said battalion to Lewistown.”[34] These two companies would further reinforce the existing military defenses at Lewistown, consisting of Capt. George Latimer’s independent company, Capt. Charles Pope’s company of the 1st Delaware Regiment, and militia forces all assembled to better protect the “Defenceless Situation of the County of Sussex.”[35]

While military forces were marching to the defense of Lewistown, various alarm stations along the Delaware required attention. Capt. Nathaniel Falconer, of the Alarm sub-committee and responsible for the signal stations, submitted an application to the Committee of Safety on April 4 requesting arms and ammunition for the station at Bombay Hook, including five muskets, ten rounds of powder and ball, and eight swivel shot.[36] To further reinforce the alarm post at the Cape Henlopen lighthouse, Fisher stationed thirty men to protect the signal. In addition to the existing thirteen alarm posts, Fisher began to fit out a new post at the False Cape (Indian River). Twenty-four men, including pilots, maintained a constant watch for the enemy at the false cape, but were now in need of both powder and signal guns. [37]

On April 7, 1776, Easter Sunday, Lewistown was presented with the opportunity to demonstrate their bolstered forces and “Yankee Play” to the British.[38] A month prior Lewistown pilot and merchant captain Nehemiah Field set sail from the port of Lewistown for St Eustatia aboard his schooner Farmer. [39] For the sum of thirty pounds, Field was hired by the Council of Safety to deliver a cargo of corn and return with any powder and arms that he could procure. Field’s voyage began prior to Roebuck’s arrival, but he promptly learned of British presence upon his return. On April 7, the alarm post at the lighthouse sent an express to Lewistown announcing Captain Field’s return and demanding assistance to unload his schooner.

The inhabitants of Lewistown provided maritime aid, ferrying soldiers from the Delaware Regiment across Lewes Creek so they could march to the support of Farmer. Field’s schooner was now grounded off Cape Henlopen due to gunfire from Roebuck’s tender, not far from where Fisher’s pilot boat remained beached. Prior to the arrival of reinforcements from Lewistown, Roebuck’s tender opened fire on the men stationed at the lighthouse with both swivel guns and cannon fire. After the cargo was unloaded the beached Farmer was able to return “a constant fire” with her two swivel guns loaded with grape shot. For two hours this engagement endured, with Roebuck’s tender sustaining heavy causalities. Finally, shots from the men stationed at the lighthouse and Farmer’s swivels were able to cut one of the halyards on the tender, causing the mainsail to collapse, thus immobilizing the vessel. Roebuck responded by sending a boat to tow her tender back to safety, ending the engagement. Capt. Charles Pope proudly wrote that “the militia officers, at Lewes, acted with a spirt that does honor to their country.”[40] The following week, the Pennsylvania Gazette praised the actions of the defenders at Lewistown, stating that “the cargoe was safely landed from the schooner and secured, without the loss of a man, either killed or wounded. The militia officers at Lewes behaved with that courage and magnanimity which does honour to their country.”[41]

Following the events of Easter Sunday, the defenses of the lower Delaware continued to be strengthened. On April 8 the Continental Brig Lexington and Continental Sloop Hornet made their way down the Delaware River and sailed through the bay avoiding capture by Roebuck. Over a week later two newly commissioned privateers, the sloop Congress and sloop Chance, each sailed down the Delaware and through the Cape May Channel, also evading Roebuck.[42] Captain Hamond was well aware that this stream of vessels, now sailing south from Philadelphia, were “fitted out with the intention of clearing the coast of our [Roebuck’s] tenders.”[43]

During late March and early April 1776, the defensive measures established on Delaware Bay held their own against the initial encroachment of the Royal Navy and Roebuck. The actions of the Committee of Safety and initiatives implemented by Henry Fisher created an infrastructure and communication network that proved vital in relaying information along the Delaware coastline. By mid-April, Roebuck remained off Lewistown, but “the town maintained between fifty and a hundred men on guard night and day at the lighthouse [Cape Henlopen], Arnold’s[44], and the creek’s mouth [Lewes Creek]; and are determined to watch them closely.”[45] In a letter dated April 17, it was stated that “Lewistown is at this time made up of officers and soldiers, and the people all together seem determined to defend our little place.”[46] Although the tides of war would soon shift, in the spring of 1776 the port of Lewistown remained Hearty in the Cause.

[1]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, September 16, 1775,” William Bell Clark ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington DC: Naval History Center, Navy Department, 1969), 2: 120-121 (NDAR).

[2]“Pennsylvania Colonial Records, X, 509, 510,” NDAR, 4:267.

[3]“Instructions from the Committee of Safety at Philadelphia to Mr. Henry Fisher at Lewis Town, Pennsylvania Colonial Records, X, 336-339,” NDAR, 2: 120-121.

[4]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, March 20, 1776,” NDAR, 4:422.

[5]John W. Jackson, The Pennsylvania Navy: 1775–1781: The Defense of the Delaware (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1974), 30.

[7]Ibid., 414; “State Navy Board, April 10, 1777, Pennsylvania Archives, Samuel Hazard et. al, eds. (Philadelphia: J. Stevens, 1852-1935), 2nd series, 1:121.

[8]“Instructions from The Committee of Safety at Philadelphia to Mr. Henry Fisher at Lewis Town,” NDAR, 2:122.

[9]Jackson, The Pennsylvania Navy, 29.

[10]Colonial Records of Pennsylvania, Samuel Hazard, ed. (Harrisburg: T. Fenn, 1831-1853), 10: 338, 352.

[11]“Pennsylvania Committee of Safety to James Maul, Philadelphia November 17, 1775, Pennsylvania Archives, 1st series, 4: 680, 681,” NDAR: 2: 1061.

[12]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Philadelphia March 23, 1776, “Pennsylvania Colonial Records, X, 523,” NDAR, 4: 483.

[13]“PRO, Admiralty 1/487; copy in Graves’s Conduct, Appendix, 112, BM. Vice Admiral Samuel Graves to Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, HMS Roebuck,” NDAR 3:112

[14]Andrew Snape Hamond to Molyneux Shuldham, March 3, 1776, NDAR, 4: 152.

[17]Muster Table, HMS Roebuck, Supernumeraries borne for Victuals entry 67, 83, 313, 94, 120, 121, National Archives of the United Kingdom (TNA), ADM 36/8638.

[18]“Henry Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, March 25, 1775. Pennsylvania Archives, 1st series, 4: 724-25.” NDAR, 4: 510.

[19]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, March 26, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 526

[20]“Journal of HMS Roebuck, Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, March 25- 31, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 595.

[21]“Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, March 26, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 529.

[22]“Henry Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, April 1, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 618-619.

[23]“Journal of HMS Roebuck, Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, March 25- 31, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 595.

[24]“List of Vessels seized as Prizes” The London Gazette, May 13, 1777.

[26]“Henry Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, April 1, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 618.

[27]John Haslet to John Hancock, April 7, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 701.

[28]Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, April 1, 1776. Papers CC (Pennsylvania State Papers) 69, I, 113-15, NA.” NDAR, 4: 618.

[29]Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, April 1, 1776, NDAR, 4: 618.

[31]“William Price to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety,” NDAR, 4: 617-618.

[32]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, April 3, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 647.

[33]“Journal of the Continental Congress, April 3, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 648.

[35]Haslet to Hancock, April 7, 1776, NDAR, 4: 701.

[36]“Minutes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, April 4, 1776,” NDAR, 4: 665.

[37]Fisher to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, NDAR, 4: 671.

[38]Pennsylvania Evening Post, April 20, 1776. “Extract of a Letter from Lewestown, 17 April 1776,” NDAR, 4: 1153.

[39]Delaware Archives: Revolutionary War in Three Volumes (Wilmington, DE: Public Archives Commission of Delaware/Chas. L. Story Company Press, 1919), 2: 944.

[40]“Pennsylvania Evening Post, April 13, 1776,” NDAR, 4:742.

[41]“Pennsylvania Gazette, April 17, 1776,” NDAR 4: 871.

[42]“Narrative of Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, April 22, 1776,” NDAR, 4:1202.

[43]Hamond to Henry Bellew, April 8, 1776, NDAR, 4: 728-30.

[44]Likely referencing land on Cape Henlopen near the property of William Arnold of Lewes Town who maintained salt works near Cape Henlopen. See Claudia L. Bushman, Harold B. Hancock, and Elizabeth Moyne Homsey, ed., Proceedings of the Assembly of the Lower Counties on the Delaware 1770-1776, of the Constitutional Convention of 1776, and of the House of Assembly of the Delaware State 1776-1781 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1986,) 284.

[45]“Extract of a Letter from Lewestown,” April 17, 1776, NDAR, 4:871.

Recent Articles

This Week on Dispatches: Raphael Corletta on the Two “Empires of Liberty”

The Milford Connecticut Cartel

Ordinary Greatness: A Life of Elias Boudinot

Recent Comments

Well written and researched. Thanks!

Thanks for a beautifully researched and written article. I have been frustrated...

There seems to be unsung heroes throughout Americas history and this gentleman...