At the onset of the Revolutionary War, coastal towns north of Boston such as Salem, Marblehead, Beverly, and Gloucester were patrolled by British naval vessels supporting troops stationed ashore and looking for smugglers. The fourteen-gun sloop-of-war Falcon commanded by Capt. John Linzee was one of these vessels.[1] Having arrived in America early in the year, it was one of several ships that provided British seaborne cover for landing troops and artillery support during the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. According to the ship’s log for that day:

Wegh’d and Shifted to the Entrance of Charlestown River and by Springs on our Cable got our Broad side to Bear on the Rebells and began to fire with Round Grape & Small Arms. Continued to fire on the Rebells till 4 PM at which Time Charles Town took fire. Our Boats Empd Carrying Wounded men over to Boston.[2]

Exactly one month after the battle, on July 17, Vice Admiral Samuel Graves gave the following orders to Linzee:

You are hereby required and directed to put to Sea as soon as possible in his Majesty’s Sloop under your Command and cruise between Cape Cod and Cape Anne in order to carry into Execution the late Acts for restraining the Trade of the Colonies And to seize and send to Boston all Vessels with Arms Ammunition, Provisions, Flour, Grain, Salt, Melasses, Wood, &c. &c. And you are here by required and directed to look into the Harbor within the Bay of Boston, and anchor therein and sail again at such uncertain times as you think are most likely to deceive and intercept the Trade of the Rebels. . . . In case of your meeting any such Rebel Pyrates either in Harbor or at Sea, you are here by required and directed to use every means in your power to take or destroy them.”[3]

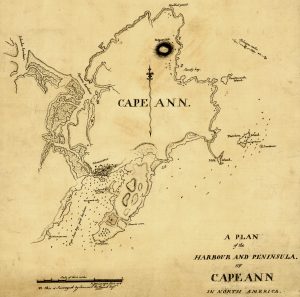

On August 5, 1775, Falcon sailed into Ipswich Bay and heaved to at Squam Harbor at the mouth of the Annisquam River. Linzee ordered the ship’s boat and crew to go ashore at Coffin’s Beach to seize sheep in a nearby pasture, mutton for the ship’s victuals. Annisquam farmer Maj. Peter Coffin, suspecting Linzee’s planned theft, alerted men working on his land as well as his neighbors. Armed with muskets the small group of defenders trekked to the beach, hid behind sand dunes, and fired upon the Falcon’s small boat as it approached.[4] The officer commanding the landing party suspected that there was a company of soldiers lying in ambush. When a militiaman’s bullet struck the brass of the lieutenant’s sword belt, the officer had second thoughts about his mission and returned to Falcon empty handed.

If a British naval ship intercepted a foreign merchant ship that was improperly documented or transporting contraband, the sale of the vessel and its cargo could financially benefit the officers and crew. For this reason, Linzee altered the lieutenant’s mission to go to a pier in Squam Harbor and inspect a deeply laden schooner suspected to be a West Indiaman with valuable merchandise onboard. Unfortunately for the British naval captain, the vessel was loaded with sand. These events led to disparaging comments in one community newspaper.[5]

Shortly thereafter, Falcon rounded Cape Ann to sail south and back into Massachusetts Bay. Linzee continued to cruise along the north shore ports and, when the opportunity presented, he impressed roughly ten seamen to serve onboard Falcon.[6] On August 8, the sloop encountered two schooners, apparently from the West Indies, bound for Salem. He took one as a prize and chased the other into Gloucester Harbor. The fleeing vessel ran aground in the inner harbor on flats near Five Pound Island. Local citizens learned of this uncommon event and then noticed the British warship with a schooner in tow. Perceiving the threat, a man climbed to the steeple of a meetinghouse and rang its bell non-stop to signal danger and alert the militia to muster.

Linzee wished to refloat and take possession of the stricken schooner. Not far from the distressed vessel was an earthen embankment strategically broken at several places to form a fort designed to keep pirates from raiding the vulnerable village. Unfamiliar with the harbor’s hidden shoals and underwater wrecks, Falcon’s captain noticed an elderly dory fisherman, William Babson of Gloucester, nearby. He took Babson prisoner and ordered him serve as their pilot.[7] Babson was reluctant to help the British captain, claiming poor eyesight. Linzee asked him to name the owner of a house on shore, which Babson did; Linzee then threatened him by saying, “I find that you can see well enough, if you let the ship strike bottom, I will shoot you on the spot.”[8] Falcon came to anchor between the headland called Stage Head and Ten Pound Island.

The streets around the clapboard houses of the town appeared almost empty as the meetinghouse bell tolled ceaselessly. Suddenly a cacophony of other sounds emanated from out in the harbor: the shrill sound of a bosun’s whistle, the rat-a-tat-tat of a drum and a chorus of officers shouting to men scurrying upon the sloop’s deck. Linzee ordered several boats over the side along with a party of sailors and marines. They were placed under the command of his first lieutenant. Meanwhile, spring lines were bent upon the anchor cable to enable Falcon to winch around and deliver port and starboard six-pounder broadsides onto the town.

Ashore, the militia prepared to interdict the British landing party. They had no cannon and little ammunition and powder. They did have two swivel guns that they mounted on carriages and moved to defensive positions. Each patriot brought along a musket to protect the grounded schooner. Local citizens gathered at a wharf near the stranded ship and on an overlook adjacent to the narrow bottom of the inner harbor. Soon two barges holding fifteen men each reached the schooner and the British sailors attempted to board and seize the stricken ship. At this point musket fire from on shore opened up on the landing party, killing three and wounding the lieutenant in the thigh. After the boat returned with the dead and the wounded officer, Linzee sent the previously-captured schooner with a British prize crew plus a cutter and other small boats with orders to fire their muskets upon any “damned rebel” within range. Then the captain ordered a cannonading of the town from the anchored naval sloop, especially toward the most thickly settled area in an attempt to draw attention away from the schooner, but “the Rebels paid very little Attention to the firing from the Ship.”

Captain Linzee’s next attempt at distraction was to set the town on fire. His report implies that he sent a party ashore to accomplish this by planting gunpowder in a suitable location but, according to his report,

I made an Attempt to set fire to the Town of Cape Anne and had I succeeded I flatter myself would have given the Lieutt an Opportunity of bringing a Schooner off, or have left her by the Boats, as the Rebels Attention must have been to the fire. But an American, part of my Complement, who has always been very active in our cause, set fire to the Powder before it was properly placed; Our attempt to fire the Town therefore not only failed but one of the men was blown up and the American deserted. A second Attempt was made to set fire to the Town, but did not succeed. The Rebels coming to the Fort obliged the four man to leave it. I then began a second time to fire on the Town but the Houses being built of Wood could do no great Damage.”[9]

The infuriated captain then sent a boat to the promontory Fort Point with orders to torch the fish-flakes near the beach.[10] This potentially destructive foray was frustrated by militia men that surrounded the site and captured the British landing party. During this landing former Gloucester resident Duncan Piper, an impressed seaman, loudly called out his own name as they reached shore, likely saving himself from being shot as an enemy.[11]

Broadsides continued to be fired into the town. Some wooden houses received a shot and one lodged into the First Parish meetinghouse.[12] The only additional loss of life the bombardment produced was that of an ill-fated hog. A local clergyman recorded:

Lindsey, Capt of a man of war, fired it is supposed near 300 Shot at the Harbor Parish. Damaged ye meeting House Somewhat, Some other buildings, not a Single Person killed or wounded with his Cannon Shot. We Retook two vessels . . . his barge & another Boat, also we took together with Them about thirty of their men, with the loss of only two of our Men. HIs Boatswain likewise in attempting to set the town on fire by firing the train of powder some combustible Matter prepared, providentially the fire was communicated to ye powder iron in his hand which occasioned an explosion and it is said he lost Hand if not his Life.[13]

The ship-to-shore battle was an American victory. The Gloucester men liberated both schooners and captured the cutter, barges and thirty-five men, several of whom were wounded, one of whom died soon after. Twenty-four of the men were sent to the American prison camp at Cambridge and the rest, who had been impressed into the navy from this and neighboring ports, were released to their homes. The captured prisoners were exchanged in the months that followed.[14] Local men Benjamin Rowe and Peter Lurvey were killed in the battle.

We hear from Cape-Ann, that a Vessel bound in there from the West-Indies, being discovered off the Harbour last Tuesday, several of the inhabitants went off in a Boat to assist in bringing her in. Soon after, about 30 armed [men] from the Man of War commanded by Capt Lindzee, boarded and took possession of the Vessel; but she running aground on the Cape, was vigorously attacked by a number of men from the town of Glocester, who soon obliged the Enemy to give up the vessel to the proper Owners, and to surrender themselves Prisoners. The whole Number was immediately sent to Ipswich Goal, in which 26 of them were confined. The Rest (4 or 5 in number) were discharged, it appearing that they had been cruelly forced into the Enemy’s Service. Lindzee was so enraged that he fired several Cannon Shot into the town of Glocester.[15]

William Babson, man who reluctantly piloted Falcon into the harbor, died shortly thereafter from unknown causes, perhaps from stress at being forced to help in Linzee’s plan.[16] The morning after the cannonading, Falcon warped out of Gloucester harbor and sailed for Boston. When Admiral Graves was informed of the Cape Ann rebels’ enmity, he ordered other coastal towns set ablaze in retaliation. This further fanned the flames of rebellion leading to the appalling burning of Maine’s Falmouth (now Portland) in the eastern Massachusetts province.[17]

[1]Captain John Linzee, as commander of the Royal Navy brigantine Beaver, came to the defense in the pre-revolutionary war destruction of the schooner Gaspee in Rhode Island. Steven Park, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee: An attack on the Crown Rule before the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2017).

[2]William Bell Clark,ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution volume 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1964), 703 (NDAR). By anchoring close to shore and using spring lines, Captain Linzee was able to rotate Falconso that both sides of the vessel could bring her sixteen guns to bear on the battle field’s targets.

[4]Melvin T. Copeland and Elliott C. Rogers, The Saga of Cape Ann (Freeport, ME: The Cumberland Press, 1960, 157.

[5]“How is the glory of Britain departed! Her Army which not long since was the terror of many nations, is now employed in cutting the throats of his majesty’s loyal subjects and sheep stealing! -Felons indeed!” Massachusetts Spy, August 16, 1775.

[6]Joseph E. Garland, The Fish and the Falcon (Charleston SC: The History Press, 2006), 108.

[7]Linzee had recently impressed several north shore seamen. Those from or near Cape Ann likely were knowledgeable about Gloucester’s harbor. It is puzzling that Linzee opted to abduct Babson to pilot his sloop into the port unless he did not trust these particular sailors under his command.

[8]Garland, The Fish and the Falcon, 109.

[9]John Linzee to Samuel Graves, August 10, 1775, ibid., 1110-1111.

[10]Fish-flakes were net-covered wooden platforms used to sun dry heavily salted codfish.

[11]John J. Babson, History of the Town of Gloucester Cape Ann (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860 and Magnolia MA: Peter Smith Publisher, 1972), 395.

[12]The 1775 cannon ball is preserved and on display at the Cape Ann Historical Society in Gloucester.

[13]Diary of Reverend Daniel Fuller, Pastor of the Second Parish Church, in James B. Conolly, The Port of Gloucester (New York, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1940), 59.

[16]Garland, The Fish and the Falcon, 109.

[17]Louis Arthur Norton, “Henry Mowat: Miscreant of the Maine Coast,” Maine History, 43 (January 2007): 1-20.

Recent Articles

John Dickinson and His Letters

North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution

The Two “Empires of Liberty:” The Fascinating Story of an American Phrase

Recent Comments

Ms. Spiegel, This is so beautifully done, IMHO, that I would love...

From your review, the naval and military professors produced an excellent primer...

Thank you, D Malcolm and good luck on your dissertation. In addition...