While brutal internecine warfare was waged in various sections of New Jersey, nowhere in the state were the effects both in length and degree felt as harshly than in the central coastal county of Monmouth.[1] The guiding principle of the war here was lextalionis, that is, the law of retaliation, whereby a punishment resembled the offense committed in kind and degree (the biblical “an eye for an eye”).[2] As one historian stated: “It is ironic that this small, rural, conservative colony was destined to experience some of the bitterest civil war in all the Provinces.”[3]

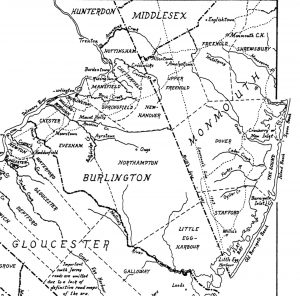

Playing an important part in this irregular warfare was New Jersey’s nearly 130-mile Atlantic coastline with numerous barrier beaches, inlets and bays.[4] Adding to this was the fact that the British, from 1776 until they departed New York City in 1783, controlled Sandy Hook at the northern end of New Jersey’s coastline.[5] Aside from protecting New York Harbor, it served as a refuge for Loyalist irregular forces and a place where they could sell plunder from their raids.[6] Another geographical factor that contributed to the extended operations of Loyalist raiders in this region was the adjacent one-million-acre section of coastal plain known as the Pinelands (also referred to as the Pine Barrens) that make up approximately 22 percent of New Jersey’s area.[7]

The Loyalist Refugee raiders in this region became collectively known as “Pine Robbers” or “Pine Banditti” because they used the extensive Pine Barrens as either their base of operation or a place to evade capture. According to historian David Fowler: “Pine Robbers were mostly poor, un-propertied elements in society who saw the war as a chance to improve their lot.”[8] An interesting aspect of these Loyalist raiders was that they included a number of runaway slaves, operating in mixed race units.[9] A more graphic description of these Loyalists is found in Barber and Howe’s Historical Collections of New Jersey (1844):

THE PINE ROBBERS: Superadded to the other horrors of the revolutionary war in this region the pines were infested with numerous robbers who had caves burrowed in the sides of sand hills near the margin of swamps in the most secluded situations which were covered with brush so as to be undiscernible. At dead of night these miscreants would sally forth from their dens to plunder, burn and murder. The inhabitants in constant terror were obliged for safety to carry their muskets with them into the fields and even to the house of worship. At length so numerous and audacious had they become that the state government offered large rewards for their destruction and they were hunted and shot like wild beasts until the close of the war when they were almost entirely extirpated.[10]

There seemed to be two distinct groups of these refugee gangs: those who operated along the fringe areas of the Pinelands, using them to evade capture; they were in the main eliminated by the end of 1779. Another set of gangs based their operations in the heart of the Pinelands and continued their activities until the end of war.[11]

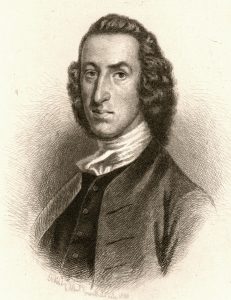

An early notice of the activities of these “banditti” who operated on the fringe of the Pinelands, can be found in a proclamation of Gov. William Livingston:

WHEREAS it has been represented to me, That a Number of Persons in the County of Monmouth, and particularly those hereinafter mentioned have committed divers Robberies, Violences and Depredations on the Persons and Property of the Inhabitants there of, and in order to screen themselves from Justice, secrete themselves in the said county: I HAVE, therefore thought proper, by and with the Advice of the Council of this State, to issue this Proclamation, hereby promising the Rewards herein mentioned to any Person or Persons who shall apprehend and secure, in any Gaol of this State, the following Persons or Offenders, to wit: For Jacob Fagan, and Stephen Emmons alias Burke Five Hundred Dollars each; and for Samuel Wright, late of Shrewsbury, William Van Note, Jacob Van Note, Jonathan Burdge and Elijah Groom, One Hundred Dollars each . . . Given under my Hand and Seal at Arms, in Princeton, the fifth Day of October, in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy-eight.[12]

So, who were these outlawed men and what were the most “grievious actions” they committed? Jacob Fagan, Lewis Fenton, and their compatriots were the classic Loyalist “Pine Robbers”: desperate, socially marginal, generally young men of questionable motivation and sometimes ambiguous allegiance who hailed from Monmouth County and whose violent acts added appreciably to the strife-ridden atmosphere in that county.[13]

Jacob Fagan, believed to be from the town of Shrewsbury in Monmouth County, began his criminal career in May 1776 when an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette of May 22, 1776 offered

Six Dollar reward—for the return of a horse taken by a Jacob Phagin alias Jameson, described as being “19 or 20 years of age, a lusty well set fellow, about 5 feet 5 or 6 inches high, straight black hair, with some freckles in the face.” Aside from the horse, he is also accused of stealing the same night: “one pair of leather breeches, about half worn, one pair of striped holland trowsers one ditto of ozenbrigs, one ozenbrig shirt, one pair of shoes, one pair of ribbed worsted stockings, and one striped silk and cotton jacket.[14]

This is the first notice of beginnings of a criminal career that had him referred to as a “monster of wickedness.”[15]

In 1777 Fagan joined the 2nd Battalion of the New Jersey Volunteers under the command of Lt. Col. John Morris. In 1778, Fagan was “detached” from the unit to go on a recruiting mission in Monmouth County.[16] It was during this period, following the Battle of Monmouth and the ensconcing of British forces in New York, that Loyalist refugee gangs became most active in the fringe Pineland townships of Shrewsbury, Freehold and Upper Freehold. In September 1778, Fagan committed his most infamous crime: the attack on the family of Capt. Benjamin Dennis.[17] The story of the attack is found in a number of histories of Monmouth County; the source is attributed to Captain Dennis’s daughter Amelia, who was fourteen years old at the time.[18]

The Dennis home was located near Howell’s Mill along the southern bank of the Manasquan River, and it was believed that Fagan had lived in the area and was familiar with the Dennis homestead. Jacob Fagan, Stephen Emmons (alias Burke), and John Van Kirk (alias Smith) entered the Dennis house while the captain was away.[19] At home at the time of the invasion was Mrs. Hannah Dennis, their daughter Amelia, and ten-year old son John. According to the story, “Smith” went in first to warn the Dennis family of Fagan’s plans. Amelia took a pocket book with $80 and fled with her brother into a nearby swamp. The bandits began ransacking the house in search of money and other valuables and became infuriated when nothing was found; Mrs. Dennis refused to reveal the hiding place. With the result, she was taken outside and hung by her neck from a cedar tree branch with a bedcord. While this was happening, Amelia saw a neighbor approaching in a wagon and with her brother ran towards him. The robbers noticed her flight and fired at them but missed. Meanwhile, Mrs. Dennis was able to free herself and escaped. The neighbor abandoned the wagon; the gang plundered it and departed. Following this incident, Captain Dennis moved his family to Shrewsbury.[20]

Not satisfied with the outcome of this first attack on the Dennis homestead, Fagan decided to return the next night and do a more thorough search of the property for valuables that he believed Captain Dennis had hidden.[21] In on the planning, Van Kirk relayed the information to Captain Dennis and an ambush was set up. “Smith” was driving a wagon with Fagan and Emmons walking behind. As they neared the ambush site “Smith” gave a signal and the militia opened fire on Fagan and Emmons. They ran into the woods but Jacob Fagan was mortally wounded and died.[22] Supposedly his body was found by “friends” and buried in the Pines; his remains, however, were not to have “eternal rest.”

The next day, a group of outraged Whigs heard of Fagan’s burial, went to the gravesite, disinterred the body and took it to Freehold. There it was placed in a tarred cloth and suspended from a chestnut tree about a mile from the Freehold Courthouse on the road to Colt’s Neck. The New Jersey Gazette of October 14, 1778 gave the following description of Fagan’s fate:

About ten days ago Jacob Fagan, who having previously headed a number of villains in Monmouth county that have committed divers robberies and were the terror of travellers, was shot. Since which his body has been gibbeted on the public highway in that county, to deter others from perpetrating the like detestable crimes.[23]

In an interesting aftermath, Captain Dennis applied for himself and his men the reward offered in Governor Livingston’s Proclamation of October 5, 1778. Their request was denied. In a letter to the New Jersey Assembly, Gov. Livingston explained why:

Trenton, December 30, 1778

Gentleman

I lay before you a Petition of Capt. Dennis in behalf of himself & party of his Company for the reward lately promised in a proclamation by the Governor & in pursuance of a Resolution of both houses encouraging the apprehension of Jacob Fagan & other Felons, but as the said Fagan was killed by the said party previous to the date of the proclamation & therefore not in consequence of it, the Petitioner cannot be entitled to the reward thereby promised. As Capt. Dennis’s men have nevertheless done a signal service to their Country by destroying the infamous robber, it is in the power of the Legislature to make them such recompence for their risque & trouble as may be a suitable encouragement for others to undertake the like Enterprizes.[24]

Following the death of Jacob Fagan, his cohorts, Stephen Emmons (alias Burke), Stephen West, and Ezekiel Williams, continued their criminal activities. In January 1779, with the help of the infiltrator John Van Kirk (alias Smith), Captain Dennis conceived a plan for their demise. Van Kirk informed Dennis that the gang was planning to go to New York to sell their plunder. Van Kirk reported they would set out by boat from Wreck Pond on the Jersey Shore.[25] In the New Jersey Gazette of February 3, 1779 was a description of the end of the remainder of Fagan’s gang:

Extract of a letter from Monmouth Court-house, January 29, 1779.

The Tory-Free-Booters, who have their haunts and caves in the pines, and have been for some time past a terror to the inhabitants of this county, have, during the course of the present week, met with a very eminent disaster. On Tuesday evening last Capt. Benjamin Dennis, who lately killed the infamous robber Fagan with a party of his militia, went in pursuit of three of the most noted of the Pine-Banditti, and was so fortunate as to fall in with them, and kill them on the spot. — Their names are Stephen Bourke, alias Emmons, Stephen West and Ezekiel Williams. Yesterday they were brought up to this place, and two of them, it is said will be hanged in chains.[26]

Governor Livingston outlined John Van Kirk’s role in bringing down these felons and noted that: “The Tories are so highly exasperated against him that death will certainly be his fate unless he speedily quits Monmouth.”[27] The “Letter from Monmouth Courthouse” in the New Jersey Gazette said: “The Whigs are soliciting contributions in his favour and from what I have already seen, have no doubt they will present him with a very handsome sum.”[28] The deaths and public display of the bodies of Jacob Fagan and his gang were not a deterrence to the Pine Robbers operating in Monmouth County—the next Pine Banditti to strike terror in the hearts of the Whigs was Lewis Fenton.

Lewis Fenton was from Freehold Township, Monmouth County where he was apprenticed as a blacksmith. According to Barber and Howe the first mention of criminal activity by Fenton was a 1777 report that he robbed a tailor shop of clothes and was threatened that if he did not return them within a week he would be “hunted and shot.” Supposedly his reply to this threat was: “I have returned your d–d rags. In a short time I am coming to burn your barns and houses, and roast you all like a pack of kittens.”[29]

His first action as a “Pine Banditti” occurred in June 1779 with his alleged involvement in the assassination of Capt. Benjamin Dennis. Dennis was returning to Shrewsbury from Coryell’s Ferry (Lambertville, New Jersey) when he was ambushed and killed, supposedly by Fenton, in July 1779.[30] Fowler states: “This act has traditionally been laid at Fenton’s doorstep and, while there is no hard evidence to back up the accusation, it is not farfetched.”[31]

The crime that would have put Fenton on a “Most Wanted List” was the murder of Thomas Farr and his family. Farr was the elderly tax collector for Upper Freehold Township; he lived near what was then known as the Crosswicks Baptist Church (today the Old Yellow Meeting House). The New Jersey Gazette carried an account of the attack on the Farr residence:

On Saturday se’nnight, about 12 o’clock at night, the house of Mr. Thomas Farr, near Crosswick’s Baptist meeting-house, was attacked by several armed men, who demanded entrance. Mr. Farr suspecting, from their insolent language, and the unseasonable time of night, their intention was to rob the house; and the family consisting only of himself, his wife and daughter, barricaded the door as well as he could, with logs of wood, and stood by one of them to support it against the assailants, who, by this time, were beating against the door with the ends of rails; but finding that they could not get. in there, fired several balls through the front door, one of which broke Mr. Farr’s leg, and occasioned him to fall, when they went to the back door, and forceably entered the house, mortally wounded Mr. Farr with bayonets, and shot his wife dead upon the spot. Their daughter made her escape after being badly wounded, to a neighbouring house. The villains finding she was gone to alarm the neighbours, and perhaps being struck with the enormity of their own barbarities, precipitately went off without any plunder, and have not yet been discovered.[32]

This crime resulted in the following Proclamation by Governor Livingston:

Proclamation

Whereas it has been duly represented to me, in council, by the oaths of credible witnesses, that in the night of the thirty-first of July last, Thomas Far and his wife were most barbarously murdered in the house of the said Far, in the county of Monmouth, by a number of persons unknown; and also that in the night of the twenty-first of June last, the house of a certain Andrews, in the said county, was violently and feloniously broke open and plundered by one Lewis Fenton, and a number of other persons unknown, and other felonious outrage and violence committed upon the persons then in said house, being the good subjects of this state; which said Fenton is also suspected to have headed the gang of those who murdered the said Far and his wife—I have therefore thought fit . . . hereby promising the reward of Five Hundred Pounds to any person who shall apprehend and secure the said Lewis Fenton . . .

Given under my Hand and Seal of Arms, at Millstone, the eighteenth day of August, in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and seventy-nine, and in the 4th Year of the Independence of America,

Wil. Livingston[33]

Following the issue of the Proclamation, the hunt for the perpetrators of the Farrs murders began in earnest, it was reported in the New Jersey Gazette on September 22, 1779 that “A few days ago four of the gang of villains, associates of the infamous Lewis Fenton, were made prisoners, by a party of our militia, in Monmouth county, and safely lodged in the county gaol.”[34] But Lewis Fenton remained at large and his eventual downfall came about in an attack on an eighteen-year-old youth, William Van Mater, who

was knocked off his horse on the road near Longstreet’s mill, in Monmouth county, by Lewis Fenton and one Debow, by whom he was stabbed in the arm and otherwise much abused, beside being robbed of his saddle. In the mean-time another person coming up, which drew the attention of the robbers, gave Mr. Van Mater an opportunity to make his escape.[35]

Van Mater then made his way to Freehold where he informed the sergeant of the guard of 1st Light Dragoons, Matthew Cusick, of what happened to him.[36]

A plan was devised where William Van Mater would drive a wagon said to contain “wine and spirits” to a tavern near where he was attacked. Hidden in the wagon were Sergeant Cusick and a few dragoons. Once near the area of the original assault, he was again stopped by Fenton, who demanded the wagon and its contents. A dragoon stood and shot Lewis Fenton through the head.[37] The body was thrown into the wagon and taken to Freehold where his corpse was put on display like other Loyalist Banditti. Later Sergeant Cusick and his party applied for and received the reward of £500.[38] David Fowler noted that: “In Shrewsbury and in Freehold Townships at least, the death of Fenton in September 1779 does seem to mark a watershed for the perpetration of such crimes.”[39]

With the demise of the Fagan and Fenton gangs, attacks by Loyalist gangs who used the Pinelands as a place to evade capture virtually came to an end in Monmouth County Townships of Shrewsbury, Freehold, and Upper Freehold, but raiders from Sandy Hook continued to operate in this area. With regards to the Pine Robber phenomenon, it continued until the end of the War of Independence but now was mainly centered in the heart of the Pinelands. A good summary of the internecine warfare in this region appeared in an 1859 Atlantic Monthly article: “Most barbarous cruelties were practiced on both sides, in the contests which continually took place between Whigs and Tories, and the unnatural seven-years’ war possessed nowhere darker features than in the neighborhood of the New Jersey Pines.”[40]

[1]The New Jersey Counties across from New York, particularly Bergen and Essex were also the scenes of depredatory British raids.

[2]For a good overview of this phenomenon see: Michael Adelberg, The American Revolution in Monmouth County: The Theatre of Spoil and Destruction(Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010).

[3]David J. Fowler, “Loyalty Is Now Bleeding in New Jersey: Motivations and Mentalities of the Disaffected,” The Other Loyalists: Ordinary People, Royalism, and the Revolution in the Middle Colonies, 1763-1787, Joseph S. Tiedemann, Eugene R. Fingerhut, Robert W. Venables, ed. (Albany: State of New York University Press, 2009), 49.

[4]The geography of the Jersey Coast also provided bases for extensive privateering.

[5]During the Revolutionary War, Sandy Hook was an island while today it is a peninsula connected to the New Jersey mainland.

[6]In the New Jersey Gazetteit was described as: “Sandy Hook, where the horse-thieves resort.”Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, vol. V, Austin Scott, ed. (Trenton: State Gazette Publishing Co. 1917), 320.

[7]In 1978 the United States Congress established the Pinelands National Reserve; in 1979 Governor Brendan Byrne signed the Pinelands Preservation Act.

[8]David J. Fowler, “Egregious villains, wood rangers, and London traders : the Pine Robber phenomenon in New Jersey during the Revolutionary War,” Ph. D. Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 1987, 304.

[9]See Joseph Wroblewski, “Colonel Tye: Leader of Loyalist Raiders – and a Runaway Slave,” Journal of the American Revolution, February 17, 2021.

[10]John W. Barber and Henry Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey(Newark, NJ: Benjamin Olds, 1844), 351.

[11]The most notorious leaders of these gangs were John Bacon, William Giberson and Joseph Mulliner.

[12]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey,5 Volumes, (Trenton: John L. Murphy, Publisher, 1901-17), 3: 465-466. In various retellings of the events involving the Fagan Gang, sometimes Stephen Emmons is listed “alias Burke,” while in others it is Stephen Burke “alias Emmons.” Unknown to Governor Livingston, Jacob Fagan had been killed in September.

[13]Fowler, “Egregious Villains,” 143.

[14]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey,

1: 104. One Perrin Phagin, sixteen or seventeen and believed to be a cousin, was also accused of this crime. There was additional six dollar reward for “bringing the thieves to justice.” They were arrested, convicted and given “twenty lashes” each as a punishment. Fowler, “Egregious Villains,” 146.

[15]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 1: 104 n1.

[16]On the rolls of Capt. Cornelius McCleese’s Company, in July 1778 he was listed as “taken prisoner June 26, 1778.” On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, royalprovincial.com.He may have been taken prisoner but escaped. Fowler, “Egregious Villains,” 149.

[17]Captain Dennis was a member of the Monmouth County Militia.

[18]Amelia married John Coryell eventually moved to Philadelphia where she died in 1844 at the age of eighty.

[19]In reality John Van Kirk – alias “Smith” was a Patriot operative who infiltrated the Fagan gang.

[20]The story of the attack on the Dennis household can be found in a number of nineteenth century New Jersey histories, including: Barber and Howe, Historical Collections, 352-353; Edwin Salter and George C. Beekman, Old Times in Old Monmouth(Freehold, NJ: Monmouth Historical Society, 1887), 36; and Franklin Ellis, History of Monmouth County, New Jersey(Philadelphia: R.T. Peck, Co., 1885), 198.

[21]It was believed that goods confiscated from a Loyalist privateer was stored on the property.

[22]Stephen Emmons escaped unhurt.

[23]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 2: 477. This area was used for public executions; at least thirteen Loyalist were hanged here and along the road to Colt’s Neck.

[24]The Papers of William Livingston, vol. 2: July 1777 – December 1778, Carl E. Prince, Mary Lou Lustig, Dennis P. Ryan and Brenda Parnes, ed. (Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1980), 487 – 488. In December 1778 the Assembly awarded Captain Dennis and his company the sum of £187.10.

[25]Wreck Pond, also known as Rock Pond, today is located between the Jersey shore towns of Sea Girt and Spring Lake. For a graphic description of how these Pine Banditti were dispatched see Edwin Salter, Old Times in Old Monmouth(Freehold, NJ: The Monmouth Democrat, 1874), 37.

[26]“Extract of a letter from Monmouth Court-house, January 29, 1779,” Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 3: 53.

[27]The Papers of William Livingston, 3: 30 – 31. In footnote 6 – 31, it mentions that Van Kirk applied for compensation for his role in the killing of Fagan, et. al. but was turned down.

[28]“Extract of a letter from Monmouth Court-house, January 29, 1779,” Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 3: 54. He did relocate to Hopewell, New Jersey in Hunterdon County.

[29]Barber and Howe, Historical Collections, 351.

[30]Steven Davidson, “The Pine Barrens: Jacob Fagan’s Gang,” Loyalist Trails UELAC Newsletter, October 28, 2012. In this article, Davidson states that Fenton was accompanied by Thomas Emmons believed to be a relative of Stephen Emmons; however, Thomas Emmons along with a John Wood had been tried in Freehold in June 1779 and was executed in July.

[31]Fowler, Egregious Villains, 161.

[32]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 3:548 – 549. The attack occurred on July 31, 1779. For a detailed description of the reasons and implications see: David Fowler, Egregious Villains, 163 – 164.

[33]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 3:571. The actual spelling is Farr. In the Proclamation Gov. Livingston offered a reward of three hundred poundsfor others involved in the Farr murders and a two hundred-fifty poundsreward for those involved in the Andrews robbery. In George C. Beekman, Early Dutch Settlers of Monmouth County, New Jersey(Madison, WI, Moreau Bros., 1901), 74, he stated that £500 was equated to $2500.

[34]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 3: 641.

[35]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey,3: 649. The area today is in Howell Township, known Adelphia (formerly Blue Ball).

[36]Henry Lee’s troops were sent to Monmouth County in September 1779 to watch for the French Fleet that was expected to come to New York Harbor. George Washington to Henry Lee, Jr., September 13, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-22-02-0338.

[37]Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey, 3: 649-650. For further descriptions of the killing of Fenton in nineteenth century histories, see: Barber and Howe, Historical Collections, 351 – 352; George C. Beekman, Early Dutch Settlers of Monmouth County, New Jersey, 74 – 75.

[38]The Papers of William Livingston, 3: 163n3. William Van Mater was so impressed with Lee’s Dragoons, he enlisted with them and served for three years.

[39]David Fowler, Egregious Villains, 171.

[40]“In the Pines,” Atlantic Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, Art and Politics, vol. III (May 1859), 566.

2 Comments

I’ve read a great deal about partisan and/or criminal activity in the Carolinas during the Rev War and have always wondered why it was also severe in New Jersey. Your article gives an interesting and convincing rationale for that. Thank you for your research and for an excellent article!

Readers: this should have been at the end of footnote 14: (Note: ozenbrig is a tough linen cloth from Germany). I had a few inquires as to what ozenbrig is.