The Fifth Virginia Convention convened in Williamsburg in May 1776 with a weighty agenda before it. The 169-year-old colony declared its independence from Britain and proposed that Congress do the same. It adopted a new constitution and a Declaration of Rights that would immediately be the model for the Declaration of Independence and later provide the foundation for the Bill of Rights. Patrick Henry became the Commonwealth of Virginia’s first governor.

The Old Dominion’s leaders remained anxious about the frontier as Indian tensions persisted. John Connolly, once the leading political and military figure at Fort Pitt, had been exposed as a scheming Loyalist. The dispute between Virginia and Pennsylvania faded when the two states’ Congressional delegations sent a joint letter to local leaders urging that “for the defence of the liberties of America” the territorial dispute be put on hold. Among the signers were Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin. The appeal was heeded, though imperfectly.[1]

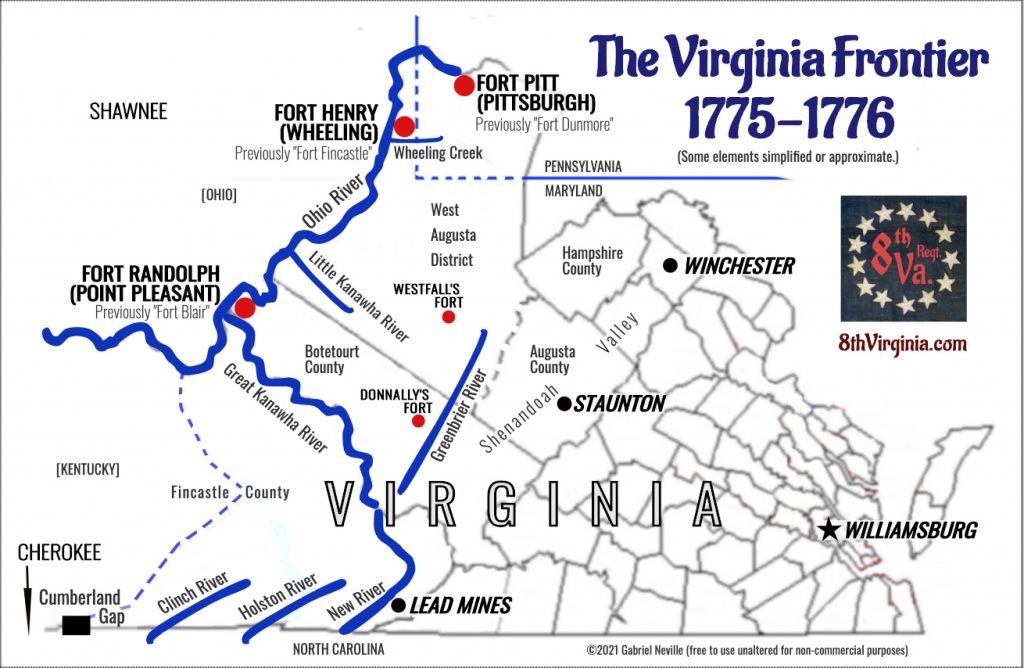

Since the 1775 independent companies’ one-year enlistments were coming to an end in September, the Convention ordered (in language indicative of the transition of government) that “four hundred men be employed for the defense of the north and north-western frontiers . . . two hundred at Point Pleasant, fifty at the mouth of Little Kanawha, fifty at the mouth of Wheeling, and one hundred at Fort Pitt, for so long as the committee of safety, or others having the executive powers of government during the recess of the legislature, shall judge them necessary.” The five new companies formed in the fall. Before long they were reassigned to Continental service, but not everyone was willing to go.[2]

Fort Pitt Company

One hundred enlisted men. Unit carried over from 1775.

Capt. Andrew Waggener

1st Lt. Presley Neville

2nd Lt. Conway Oldham

Ens. Daniel Hollebeck

First Point Pleasant Company

One hundred enlisted men. Unit carried over from 1775.

Capt. Matthew Arbuckle

1st Lt. Andrew Wallace

2nd Lt. Samuel Woods

Ens. John Gallagher

Ens. James McNutt

Ens. John Williams

Second Point Pleasant Company

One hundred enlisted men, raised in Botetourt County.

Capt. William McKee

1st Lt. William Moore (killed in action)

1st Lt. James Thompson (promoted)

2nd Lt. James Thompson

2nd Lt. James Gilmore (promoted)

Ens. James Gilmore

2nd Lt. John Moore (promoted)

Ens. John Moore

Little Kanawha Company

Fifty enlisted men, raised in Augusta County.

Capt. Michael Bowyer

Lt. Robert Gamble

Ens. John McDowell

Wheeling Company

Fifty enlisted men, raised in Hampshire County.

Capt.-Lt. Stephen Ashby

1st Lt. Lt. Ebenezer Zane

2nd Lt. Benjamin Casey

Ens. Richard Routt

The captains at Fort Pitt and Fort Randolph were authorized to give a twenty-shilling bounty to men who reenlisted and to otherwise recruit as necessary. The additional Point Pleasant company was raised in Botetourt County. The Little Kanawha company was raised in Augusta County. The new Wheeling company was raised in Hampshire County. This time, no regulars were raised for the southwest frontier. Instead, Col. William Christian was sent with a militia army to deal with the Cherokee by burning their crops and villages. Remnants of William Russell’s 1775 company may have participated.[3]

Changes were also made to Virginia’s frontier political geography in 1776. The western “district” of Augusta County was finally separated and divided into three new counties: Ohio, Monongalia, and Yohogania. Fincastle County, too, was eliminated and divided into Kentucky, Washington, and Montgomery counties.

The Fort Pitt Company

John Neville had commanded the senior West Augusta company for 1775-1776 and held command over all of the Ohio River companies. He was elevated to major and Lt. Andrew Waggener was promoted to succeed him on June 20, 1776. Waggener’s uncle, Thomas Waggener, had been a junior officer under Lt. Col. George Washington at Jumonville Glen and Fort Necessity in 1754. Though Neville’s men had come from Winchester, it is clear from pension records that most or all of the new enlistees came from the settlements around Fort Pitt. Neville’s son, Presley, became the company’s senior lieutenant. Conway Oldham and Daniel Hollebeck served as lieutenant and ensign, respectively.[4]

John Gerard’s pension claim reveals the path followed by many of Neville’s original enlistees. Gerard was a volunteer when he first arrived at Fort Pitt. The men were then enlisted as a company of provincial regulars in the fall of 1775. He then reenlisted in 1776 (perhaps truncating his original enlistment) for two years, the standard term for 1776 enlistments in Virginia. Six months into the new enlistment the company was transferred to the 12th Virginia Regiment and the Continental Army. The terms of their State enlistments still applied, resulting in a remaining service commitment of eighteen months.[5]

Philip Main lived in West Augusta when he joined the company. He recalled that “he enlisted on George’s Creek up the Monongahela [River] above Redstone old Fort” and “was first marched to what was then called Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) was then sent under Lieutenant Connaway Oldham to guard provisions down the Ohio River to the mouth of Big Canawa [River.] after staying a few weeks at the mouth of Canawa, returned to Fort Pitt & was stationed there until the next spring.” More on the expedition to Point Pleasant is found in a petition from three soldiers who reported that while “on the Fort Pitt Station” they “were Ordered on Command by the Commanding Officer, to Escort a Quantity of Provisions for the Garrison at Fort Randolph.” However, “on the Night of the 25th of December l[o]st the Boat by running on a snag stove; by which each of them lost their Rifles, together with sundry Cloathing.” A stump or log in the river punctured the side of their boat, causing them to lose their most valuable equipment.[6]

When reassigned, Waggener’s men headed back to Winchester to rendezvous with Col. James Wood. “In the month of April 1777,” Main recalled, they “marched from Fort Pitt through Virginia by the way of Winchester, from thence to Lancaster Pennsylvania from thence to Philadelphia, crossed the Delaware above Trenton at Carrells [Coryell’s] Ferry & joined the Grand Army at Bonbrook [Boundbrook] in Jersey.”[7]

Andrew Waggener was promoted to major, taken prisoner, exchanged, and witnessed the victory at Yorktown. All four of his brothers died in the war. Presley Neville married Gen. Daniel Morgan’s sister and played a key role in the growth of Pittsburgh. Conway Oldham was killed at the Battle of Eutaw Springs.[8]

The First Point Pleasant Company

Two hundred miles downriver from Fort Pitt, Matthew Arbuckle remained in command of the garrison at Fort Randolph, guarding the mouth of the Kanawha (or “Great Kanawha”) river. Any north-flowing river emptying into the Ohio was a likely route for Indian warriors crossing to the south. The opposite was true as well. Frontier leader John Stuart recalled that the garrison was needed “to prevent and intercept the Indians from crossing the Ohio to our Side, as well as to prevent any Whites from crossing over to the side of the Indians, and by such means to preserve a future peace.”[9]

Stuart also remembered that after Virginia established self-rule

another company was ordered to the Aid of Capt. Arbuckle’s Garrison, to be commanded by Capt. William McKee[.] But the Troubles of the War accumulated so fast that it was found too inconvenient and expensive to keep a Garrison at so great a Distance from any Inhabitants, as well as a Demand for all the Troops that could be raised to oppose British Force. Capt. Arbuckle was ordered to vacate the Station and to join Genl. Washington’s Army, but he was not willing to, having engaged, as he alleged, for a different service.[10]

The Convention had in fact been clear that the transfer was not mandatory. Stuart wrote, “A Number of [Arbuckle’s] Men, however, marched and joined the Main Army until the Time of their Enlistment expired.” Militiaman Jacob McNeil likewise remembered that “At the fort were regular soldiers—many of whom were marched elsewhere.” Leading them was Lt. Andrew Wallace who was promoted to captain in the spring, perhaps in Arbuckle’s stead. Though some simply served out their terms, others were convinced to reenlist for three years—the standard term for 1777 enlistments in Virginia. Lawrence Conner “enlisted as a Soldier under Capt. Arbuckle, to go on an expedition against the Shawanee Indians, for two years, and before said two years had expired he reenlisted as a Soldier under Capt. Wallace, of the 8th Regiment, of the Virginia Continental State line.” (The 12th Virginia was redesignated the 8th in September 1778.)[11]

Those who stayed with Arbuckle were not idle. Chief Cornstalk reappeared and warned that most of the Shawnee were now allied with the British. Arbuckle, following a common practice, held the peace-minded chief as a hostage to fend off an attack. At Fort Pitt, meanwhile, the new commandant, Gen. Edward Hand, was planning his own offensive against the Shawnee. When militiamen from Botetourt County arrived at Fort Randolph to rendezvous with Hand, one of their officers was ambushed, killed, and scalped while hunting turkeys on the Virginia side of the Ohio. “As pale as death with Rage,” several vengeance-seeking militiamen stormed the fort and killed the innocent Cornstalk. “A few days after this Catastrophe,” Stuart wrote, “Genl. Hand arrived, but had no Troops, and we were discharged.” Arbuckle must have known that the departing militia had just made life much harder for his garrison.[12]

Captain Arbuckle remained active on the frontier until he was killed in a storm by a falling tree in 1781. Andrew Wallace was killed at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.

The Second Point Pleasant Company

The career of the junior Point Pleasant Company tracks closely with that of the senior one. When Arbuckle declined to join the Continental Army in 1777, Irish-born Capt. William McKee did the same. Subaltern officers Lt. James Thompson and Ens. John Moore opted to go while Lt. James Gilmore remained behind. Enlisted men were also allowed to choose. James Bryans remembered that he “enlisted . . . in the year 1776 under Captn. Wm. McKee for the term of two years—that Captn. McKee was stationed at Point Pleasant in Virginia. That during the time of his service, Captn. Andrew Wallace came to Point Pleasant, & such soldiers as chose had permission to join him & serve out the time of their inlistment in the regular army—that he . . . [joined] the said Wallace & became attached to the 12th Virginia Regiment.”[13]

Many who remained behind believed (or later said they believed) they belonged to the 12th Virginia as well. Pension applicant Goolsberry Childers enlisted “for the term of two years in October or November 1776 in the Company commanded by Capt Wm McKee . . . & attachd to the 12th Virginia Reg’t. on Continental establishment, that he marched under his said Capt in march 1777 to Point Pleasant where he remained in the service untill the fall of the year 1778.” John Entsminger said that “he never joined his regiment and that the colonel never visited the garrison where he was stationed.”[14]

The murder of Cornstalk destroyed any chance for peace with the Shawnee. A few days after the trouble-making militia went home “a small party of Indians appeared near the fort,” Stuart recalled. “Their Design was to retaliate the Murder of the Cornstalk.” McKee ordered Lt. William Moore to pursue them. “Moore had not proceeded over one quarter of a Mile, until he fell into an Ambuscade and was Killed with several of his Men.”[15]

In May of 1778, McKee took command of the garrison while Arbuckle was visiting his home in the Greenbrier River valley. A small band of Indians approached the fort and then retreated in feigned terror, repeating the tactic they had used on Lieutenant Moore. When that failed, Stuart reported that “their whole Army rose up at once, and showed themselves, extending across from the Bank of the Ohio, to the Bank of the Kanahway, and commenced to Fire on the Garrison.” According to William Pryor, “they killed one man Paddy Shearman and wounded Lieut Gilmore.” After hours of shooting and a pointless parley, the Indians decided to find an easier target. They rounded up the garrison’s cattle herd, killed what they couldn’t use themselves, and headed south up the Kanawha toward the Greenbrier settlements—Arbuckle’s home.[16]

Veteran John Jones remembered that the Shawnee, “being compelled to abandon the attack” on Fort Randolph “directed their march to Donnally’s fort . . . on the frontier of the inhabited part of the County of Greenbrier.” (Greenbrier County was created the same year from Botetourt and Montgomery counties.) According to William Pryor, McKee was warned by Cornstalk’s sister Nonhelema, known as the “Grenadier Squaw.” He offered furloughs to any two men who would volunteer to outrace the war party and warn the Greenbrier settlements. Two men set off but returned the same night, too frightened to proceed.[17]

after they returned Philip Hammond and myself agreed to go, when my elder brother [John] Pryor saying that he was more experienced in Indian Warfare and finding that Hammond preferred that my brother should go I gave way, and they were dressed in Indian style by the Grenadier Squaw, and followed the Indians and passed them at the meadow within ten or twelve miles of Donnelleys fort.[18]

Warned in time, the settlers—Arbuckle included—defended themselves in the stockaded community stronghold. The Shawnee put down their firearms and approached silently at dawn with war clubs and tomahawks. Hammond and “an old Negro” named Dick Pointer raised the alarm as the attackers splintered the door with their weapons. Pointer provided critical service, holding the attackers off by firing swan shot at them with a musket while the other men awoke, went downstairs, and ran from the far end of the fort. A day-long fight ensued, after which the Indians gave up. Four settlers and seventeen Indians were killed. The attackers, said Zedekiah Shumaker, were “dreadfully worsted.”[19]

Back at Fort Randolph in the fall, Captain Arbuckle placed a man named Morgan under guard. He had lived for many years among the Indians, initially as a prisoner, and had an Indian wife. Morgan’s father had offered a $300 reward for his return. The man escaped near the end of the year when the garrison’s two-year enlistments were about to expire. “Capts Arbuckle and McKee,” Shumaker said, feared “that he would give information to the Indians of our situation.” With soldiers at liberty to go, the garrison was weakening every day. The officers decided it was better to close the fort than to string things out with a vulnerable force. “this induced the officers to leave the fort sooner than they intended, and I was discharged.”[20]

Private Jones spent the next two years as a “spy,” patrolling a sixty- or seventy-mile stretch of western Greenbrier County. Years later, when he applied for a veteran’s pension, he was unable to “state with precision the character of his engagements under Capt. Arbuckle, whether he belonged to the Virginia Continental line[,] State volunteers or Virginia Rangers.” This would be a problem for many of the Fort Randolph men. Captain McKee survived the war and later served as a delegate to Virginia’s convention to ratify the U.S. Constitution. Persuaded of its merits, he voted to ratify despite instructions from his constituents that he oppose.[21]

The Little Kanawha River Company

The fifty-man company organized for the mouth of the Little Kanawha was led by Capt. Michael Bowyer, Lt. Robert Gamble, and Ens. John McDowell. Bowyer was a native of Augusta County, a member of the committee of safety, and co-author of the early revolutionary Augusta Resolves.[22]

A soldier named Christopher Barlow remembered, “In this service there was but a single company embodied, and we were not attached to any Redgiment, and had no colonel or major during the time for which he enlisted. . . . This force was sent out to the frontiers of the state of Virginia, for the purpose of guarding the settlers from the invasions of the Indians, who were . . . in the frequent habit of committing depredations upon the settlements of the whites.”[23]

One of Bowyer’s soldiers was a secret Loyalist. William Grant wrote a detailed but occasionally exaggerated account of his experiences for the British after he defected in September of 1777.

At that time I taught a school in Augusta County, but being zealous for government was determined not to go, finding I was not able to withstand their power, which was very arbitrary in that part, I thought it better to enter into the service against the Indians than to go into actual service against my Countrymen. Accordingly some troops were raising at that time by Act of the Convention of Virginia (to be stationed at the different passes on the Ohio to keep the Shawneese &c in awe and to prevent their incursions) upon these terms, vizt that they should enlist for the term of two years, that they should not be compelled to leave the said frontiers or be entred into the Continental service without their own mutual consent, as also that of the legislat[ure].

Taking this to be the only method of scree[n]ing myself from being deemed a Tory and also of preventing my being forced into the Continental service, I enlisted the third of Septemb[e]r into Capt. Michael Bowyers’s Company of Riflemen, to be stationed at the mouth of the Little Kennarah upon the River Ohio.[24]

The company assembled at Staunton, the Augusta County seat. Lieutenant Gamble recalled, “our destination then was to form at the mouth of the Little Kanawha, or other parts of the Western Country which Circumstances might require for the Term of two years . . . But in consequence of sundry murders committed by the indians on the waters of & on Tygarts Valey Governor [Patrick] Henry sent an Express which ordered [us to go to] Tygarts Valey.” Private Barlow was more specific, recording that they “marched to Tigers Valley on the head or near the head waters of the Monongahala River, at West Falls [Westfall’s] fort.”[25]

Gamble wrote, “The Legislature in December 1776 attached this company with others similarly situated to the 12thVirginia Regiment commanded by . . . Colo James Wood. In consequence they were marched to join the american army; when in Winchester proposals of reenlistment was made & many of the Men enlisted for three years or during the Warr.” Several men “declined reenlisting but proposed if they were permitted always to serve under my command that they would serve three years.” Unlike the men from Fort Randolph, it appears that Bowyer’s entire company joined the main army in New Jersey. Sergeant Grant’s scheme for avoiding Continental service had failed. The company joined the regiment in time to fight at Brandywine in September.[26]

Years later, Gamble singled out one of the reluctant enlistees for praise. At Brandywine Thomas Galford was wounded “by a musket Ball in the knee. His left thigh shrunk & caused him to halt in consequence[.] I had him appointed orderly Sergeant which rank he held when discharged. But a reluctance to be Called a pensioner induced him to decline application for support altho in low Circumstances.” Captain Bowyer settled in Greenbrier County and later corresponded with Thomas Jefferson about the mysterious giant fossilized bones that were located nearby at Big Bone Lick. The bones have since been identified as those of a mastodon.[27]

The Wheeling Company

The Wheeling company of 1776 was led Capt.-Lt. Stephen Ashby, who was older than average for his position—born about 1725. A note on a list of 12th Virginia officers provides important information on the formation of this company. The Hampshire committee “elected Stephen Ashby Captain, Benjamin Casey Lieutenant and Richard Routt Ensign.”[28]

The Officers appointed raised a part of the Quota assigned them and marched them to the station in Expectation of making up the Defficiency out of a Lieutenant’s Command which was then stationed at the Place and Commanded by a Lieutenant Ebenezer Zane. By the testimony of Lieut. Col. Nevill the men commanded by Lieut. Zane wou’d not agree to enlist in the Service of the State unless Zane could have a Command, that he (Col. Nevill) thinking it for the good of the service, that the Numbers should be augmented to a full company Directed Lieut Zane to enlist his Quota of men, which he completed, and that he did appoint him to act as first Lieutenant of the Company, that he took the earliest Opportunity of acquainting the Governor with his Proceeding which met with the Governor’s entire approbation.[29]

Like Arbuckle and McKee, Zane felt his first duty was to his community around Fort Henry. The note above concludes: “Lieut. Zane has since the above Proceedings Declined to accept of a Continental Commission.” Captain Ashby took the company to New Jersey without him. When the Virginia Line was consolidated in September of 1778, Ashby was entitled to keep his commission but opted to retire, deferring to a younger man.[30]

Status and Pension Issues

Like Stephenson’s company a year before, all five of the 1776 independent companies were taken into Continental service. Recruiting had grown difficult as the most eager men were already enrolled and as the initial rage militaire subsided. The General Assembly consequently turned to its independent frontier companies, formally noting that there were “in service of this commonwealth five companies of land forces stationed at different posts on the river Ohio, whom it may be expedient to engage.” The governor was authorized to take “so many of the companies stationed on the Ohio as shall be willing to be of the armies of the United States.” A January 1777 (but extendable) deadline was set for the formation of the new regiments. All five frontier companies were assigned to the 12th Virginia under Colonel Wood.[31]

The legislature, however, had said that the companies should join the Continental Army if they were “willing.” Sergeant Grant’s understanding was that they could “not be compelled to leave the said frontiers or be ent[e]red into the Continental service without their own mutual consent, as also that of the legislat[ure].” He was right. The same promise had been made to the soldiers of Colonel Russell’s 13th Virginia. (Russell’s regiment was raised entirely in the West Augusta District and its successor counties, and was consequently known as the West Augusta Battalion.) The question of posting was not just a matter of personal pique or convenience. Russell explained the issue to General Washington a year later at Valley Forge.

That the Soldiers of that Regiment had assurances by the Officers who enlisted them to be continued on that side of the Mountain, is a fact, perhaps unknown to your Excellency, but true it is such engagements drew in many married Men to enlist, who have since been forced down here, leaving their helpless Families in a most miserable condition. Their Wives and Children were soon after forced to fly into Forts, to escape the danger of a savage Enemy, at a time when provisions were scarce in that part of the Country and must have suffered much since.[32]

Ignorant of or not concerned with this, Congress resolved on January 8, 1777

That, pursuing the idea of Congress for quickly reinforcing the army, the governor of Virginia be desired . . . to order Colonel Wood’s [12th Regiment] and the West Augusta [Russell’s 13th] batallions to march immediately by the nearest routs to join General Washington in New Jersey; leaving proper recruiting officers behind to complete the batallions, if they are not already full, and to follow on with their recruits.[33]

Yet, by the terms of their engagements, they could not be forced to go. Arbuckle, McKee, and Zane refused to, as did some enlisted men. Pay rolls for the 12th Virginia reveal, consequently, that the regiment could not report a full complement of ten companies until October. The unique example of Sergeant Grant, on the other hand, shows that enlistees in at least one company were not given a real choice.[34]

The enlisted men were aware of their rights in other ways as well. Frontier soldiers typically provided their own rifles. When they joined the main army, the men were required to exchange them for muskets. In May, Maj. George Lyne of the 13th Virginia wrote to the Board of War on behalf of fourteen soldiers in Capt. Bowyer’s company, begging “leave to petition That their Rifles, Powder Horns, etc. may be rec[eive]d by the Commissary General of Military Stores & that they receive for them a reasonable price.”

The matter stands as thus: by an Ordinance of our Convention the Company amongst others was raised for the purpose of defending our Frontiers and not to be drawn from thence without their consent, and each man that furnished himself with [a] Rifle was to receive for the use 20s [shillings] Per Annum, since which these men have been taken into the Continental Service & marched with their consent from Monongahalia to this place that they had neither an opportunity of seling them, or lodging them at their homes; No man’s Goal in support of the common cause ought to operate to his prejudice, that I trust they will receive the value of their Rifles & refer to the Capt[ain]’s list inclosed.[35]

Status questions for those who remained on the Ohio inevitably arose. Were they state troops or Continentals? Companies of the 13th Virginia had been left at Fort Pitt and were regarded as Continentals, so why not Arbuckle’s and McKee’s men? There is no evidence that this question was litigated at the time, but when pension laws came into effect it became an important question.

On September 25, 1778 Captain Arbuckle made out a discharge for Pvt. Simon Acres. The soldier had, he wrote, “served as a soldier in my Company of Regulars belonging to the 12th Virginia Regiment.” Arbuckle evidently believed he was a captain in the 12th Virginia. Supporting a bounty land claim for Arbuckle’s heirs, William McKee likewise said Arbuckle “serv’d in the capacity of a Captain being together with all the troops stationed on the Ohio incorporated into the 12th Virginia regt. on Continental Establishment.”[36]

Others were not so sure. Private Pryor confessed in 1832 that he “enlisted under said Arbuckle in the latter part of the year 1776 for two years but whether he belonged to the State troops or continental does not know.” John Jones and Christopher Barlow said much the same. One veteran evidently used the confusion to falsely claim Continental status. John Jemison said he “enlisted a soldier in the Continental Army on the 16 October 1775 . . . and was attached to the company commanded by Captain Matthew Arbuckle, and the 12thVirginia Regiment, commanded by Colonel John Neville—that said term of enlistment was for one year.” The 12th Virginia, however, didn’t even form until four months after Jemison’s enlistment expired.[37]

Conclusion

Officers and men from the frontier companies fed into four Continental regiments: Virginia’s 7th, 8th, 12th, and 13th. The latter three were frontier-based regiments and men in the latter two signed on expecting to be defending their homes. James Crockett of Captain Russell’s 1775 one-year company recruited a new company for the 7th Virginia. The 8th Virginia included one entire company (Capt. John Stephenson’s from 1775) that had been formed for service at Fort Pitt, and a company recruited by Capt. James Knox and James Lt. James Craig (who were, like Crockett, veterans of Russell’s company). The 12th Virginia included parts of all five of the two-year 1776 companies, leaving behind those officers and men who refused to go. The 13th Virginia’s senior company was formed by Capt. Robert Beall and Lt. Simon Morgan (veterans of Stephenson’s company) who reenlisted a number of Stephenson’s men.[38]

Virginia’s independent frontier companies were created to respond to significant and immediate threats that faced the colony at the time of the Royal government’s ouster. When the Continental Army’s Quebec campaign failed, the British regained the ability to supply Indians and apply pressure to the Americans in the west. The Continental Army established a garrison at Fort Pitt in 1777 under General Hand, taking control of the upper Ohio and aiming to take the British base at Detroit. Still, Virginia State forces like Joseph Crockett’s remained active in the wilderness throughout the war. The most famous of the later units was George Rogers Clark’s Illinois Regiment.

After Independence, the new nation stretched to the Mississippi and Virginians migrated west in huge numbers. While Kentucky remained a Virginia county until 1792, the Old Dominion agreed to cede the headwaters of the Ohio to Pennsylvania in 1780. It gave its claims across the river to the national government after the war. Five states and a portion of Minnesota were created from the territory. These post-Revolutionary developments so important to the future of the United States were by no means certain when the war began. The groundwork for these successes was laid by the independent Provincial companies that asserted Virginia’s western claims almost from the day Lord Dunmore left the colony.

[1]Patrick Henry, et al., “Virginia and Pennsylvania Delegates in Congress to the Inhabitants West of Laurel Hill,” July 25, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives.

[2]William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large, Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619, 13 vols. (Richmond, J. & G. Cochran, 1819-1823), 9: 135-136.

[3]Hening, Statutes, 9: 136-137; Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 49; Gail S. Terry, “William Christian (ca. 1742–1786),” Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia (LVA); David Gamble pension S32264.

[4]Andrew Waggener bounty land warrant file, LVA;The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Benjamin L. Huggins, ed. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013) 22: 382–383n3; Papers of Washington, Colonial Series, W. W. Abbot., ed (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983) 1: 107–115, 209-210; Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of the officers of the Continental Army during the war of the revolution (Washington, DC: Rare Book Shop Publishing, 1914), 563;Thomas Bull pension S32153; Heitman, Register, 563. All pensions applications accessed at Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, revwarapps.org.

[5]John Gerard pension S42740.

[6]Philip Main pension S13850; Legislative Petition of James Duncan, Richard Reeves, and William Grilles, LVA; Matthew Arbuckle bounty land warrant file, LVA.

[7]Main pension; see also John Vandman pension W6355.

[8]Martisburg Gazette, May 1813, cited in B.G. McMechen SAR application, June 10, 1898.

[9]John Stuart, “Narrative by Captain John Stuart of General Andrew Lewis’ Expedition Against the Indians in the Year 1774, and of the Battle of Point Pleasant, Virginia,” Magazine of American History, 1 (1877): 740-750, 745; Zedekiah Shumaker pension S7480, and Jacob Kinnison pension S16905.

[11]Lawrence Conner pension S35853; Jacob McNeil pension S5745; Stuart, “Narrative,” 745; Heitman, Register, 566. See also Alexander Reid pension S36872.

[12]Samuel Kercheval, A History of the Valley of Virginia, 3rd ed.(Woodstock, Va: W.N. Grabill, 1902), 200; John Jones Pension W7920; Stuart, “Narrative,” 748; William Pryor pension S8979; Shumaker pension; Daniel Davis pension S8287.

[13]National Archives, Compiled Services Records . . . Revolutionary War, 1076: 783-802, 1077:860-867 (CSR); Heitman, Register, 249

[14]John Entsminger pension S42708; Goolsberry Childers pension S30924; James Bryans pension S39244. See also Thomas Sewell pension S40394.

[15]Stuart, “Narrative,” 748; National Archives,CSR, 1076: 783-802. Stuart only identifies “Lieutenant Moore,” but John Moore is known to have survived.

[16]Stuart, “Narrative,” 748; Pryor pension.

[19]Stuart, “Narrative,” 748-750.

[20]Shumaker pension. See also Pryor pension.

[21]Jones Pension; George Wilson McKee, The McKees of Virginia and Kentucky (Pittsburgh: J.B. Richards, 1891), 66-67.

[22]Jim Glanville, “The Fincastle Resolutions,” Smithfield Review, 14 (2010): 104-106.

[23]Michael Bowyer bounty land warrant file, LVA; John Slaven pension S6110; John McDowell pension S30578; Christopher Barlow pension W8341; Robert McCorkel pension S9430.

[24]“Narrative of William Grant” in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, Procured in Holland, England and France, E.B. O’Callaghan, ed. (Albany: Weed, Parson and Co., 1857), 8: 728-734. E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra, Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1783 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1978), 67.

[27]Slaven pension; The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Barbara B. Oberg, ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 38:621–622, 626–627.

[28]National Archives, CSR, 1074:487, 1077:1224-1225; Benjamin Casey bounty land warrant, LVA; Edward Roberts pension W8560; Jacob Wheat pension W6481; James Johnson pension S36636; Vincent Tapp pension S41231; Lewis Howel pension W9719; Heitman, Register, 475.

[30]Stephen Ashby bounty land warrant BLWt2420-300; all bounty land warrants with BLW numbers accessed at Southern Campaigns Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, revwarapps.org.

[31]Hening, Statutes, 9:179-180.

[32]Papers of George Washington, 13: 656–657.

[33]Journals of the Continental Congress,W.C. Ford, ed., 34 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904-1937) 7:21.

[34]Andrew Waggener bounty land warrant BLWt2323-400; Entsminger pension; National Archives, 12th Va. payrolls for July, August, and October 1777, M246; Reid pension.

[35]George Lyne to Board of War, May 19, 1777, National Archives, M247.

[36]Hening, Statutes, 9:179-180; Matthew Arbuckle, William Arbuckle, and James Thompson bounty land warrant files, LVA. The Thompson file identifies a number of enlisted men.

[37]James Thompson bounty land warrant, LVA; Pryor pension; Christopher Barlow pension; John Jemison pension S36623.

[38]Samuel Murphy pension S22413; Thomas Ravenscraft pension S1248.

One thought on “Virginia’s Independent Frontier Companies, Part 2 of 2”

Really well-done series. Tracking the movements of soldiers in and out of semi-regular, regular, militia, and ad-hoc frontier military units is a demanding task and you’ve done a fantastic job. No doubt I will be referring back to these articles time, and time again.

Thank you!