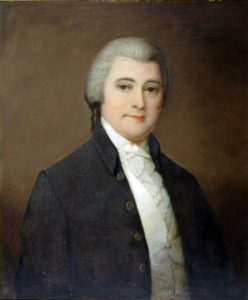

It is easy to suggest that William Blount made no significant contribution to the development of the United States. His achievements, although not negligible, were only on par at best, and far less than many of his more famous contemporaries. Blount served in the North Carolina militia during the American Revolution, but with little acclaim as a paymaster. From a prominent and influential Southern colonial-era family, he was an unremarkable member of his state’s House of Commons and later the state’s Senate. He served as a delegate to the Confederation Congress, unsuccessfully seeking its presidency, and to the Constitutional Convention where his contributions were little better than negligible. As Territorial Governor of the Southwest and Superintendent of Indian Affairs, he performed adequately. As one of Tennessee’s first federal senators, Blount finally achieved historical immortality, but for reasons he did not originally envision. He has the infamous distinction of being the first federal official, elected or appointed, to be impeached under the new republic’s Constitution for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” The trigger for the impeachment was a letter in Blount’s own hand implicating him and his followers in a scheme to forcibly seize Spanish Florida and Louisiana for the British Crown.

This monumental first test of the Constitution’s impeachment authority cannot be labeled a partisan political battle, as many charged, one of many that embroiled the nation at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. Although partisan politics did eventually engulf the affair, President John Adams and his administration ethically and morally followed the duties and dictates of their offices instead of sweeping the matter under the carpet. Their action was supported by the one individual who could be viewed as above biased party and private interests: former President Washington endorsed the government’s pursuit of the affair, writing that, “It will be much regretted, much, if this business is not probed to the bottom.”[1] Adams believed his actions were validated: “A conspiracy was fully proved, to dismember the empire, and carry off an immense portion of it to a foreign dominion.”[2]

Most historical interpretations stress that Blount, despite his wealth, political connections, and influential friends, was nothing more than a greedy land speculator who abused the power and prestige of his appointed and elected offices. According to Buckner F. Melton, Jr., Blount displayed “a shrewdness and a degree of self-interest that would continue to rival his loyalty to the established political regime” with these traits growing “even stronger with time.”[3] John C. Miller contends that Blount was originally “a Federalist who had become rich by using political office to further his business interests.”[4] William H. Masterson echoes this belief that “his first army office, political place and power were to Blount the handmaidens of business power” and “he was a businessman in politics for business.”[5] Arthur Preston Whitaker labels Blount “literally a land-jobber.”[6] Andrew R. L. Cayton feels that “it was the pursuit of personal profit that gave” Blount “the direction for his life and “ordered the rest of his existence” with his “eyes always on the bottom line.”[7] One biographical work makes a weak attempt to vindicate or excuse Blount from the conspiracy that bears his name. General Marcus J. Wright’s 1884 work states that Blount was “defamed and traduced for a brief period in his life by the followers of a strong partisan administration.”[8] The consensus among historians about Blount’s continual quest of wealth is neatly summed up by the denouncing question asked by Abigail Adams: “When shall we cease to have Judases?”[9]

William Blount, a third-generation American and eldest of eight siblings, was born in 1749 on his influential family’s Rosenfeld Plantation located near the Pamlico Sound region of North Carolina. The Blount family interests included cotton and tobacco farming with slave labor; the raising of cattle and hogs; the production and sale of maritime tar, pitch and turpentine; the mining of minerals, metals and additional ores; corn and the milling of other grains; saw mills and distilleries; and money lending. From his boyhood, Blount and his brothers “were accustomed to versatility of enterprise.” As with many rural Southern families, the Blounts were integrally linked economically, commercially, and socially with their relatives and they “acted in concert with a constant family interest.”[10]

Blount’s career of public service was almost continuous from 1777 until the end of his life in 1800. In 1780, as the fighting of the Revolution erupted in the Carolinas, he began a four-year stay as a member of his state’s House of Commons and moved to the state’s Senate for a two year-term in 1788. Blount had previously shown interest in political office in 1779, when he ran for the Assembly against Richard Dobbs Spraight, coincidentally later a fellow delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention; however, the election was declared illegal as both candidates strongly advocated dishonest voting.[11] Until finally securing his election to North Carolina’s Lower House, Blount continued to occupy his time with business, militia matters, and with his family’s vast holdings, providing considerable statewide authority during a time of unchecked inflation. Blount even earned the resentment of his own cousin, Declaration of Independence signer Thomas Hart, who intimated that his relative was a usurer.[12] Blount was later appointed a delegate to the Confederation Congress in 1786 and 1787 and concurrently was a member of the Constitutional Convention.

James Madison’s sole comment on Blout indicates that he was most attuned to Blount’s character: upon the completion of the Constitutional Convention, Madison wrote that Blount “declared that he would not sign, so as to pledge himself in support of the plan, but he was relieved by the form proposed and would without committing himself attest to the fact that the plan was the unanimous act of the States in the Convention.”[13] Blount’s evasive short answer speaks volumes on his ingrained trait of playing both sides of the fence for his own benefit.

On May 26, 1790, the area between Kentucky and the present states of Alabama and Mississippi, formerly claimed by North Carolina, was Congressionally designated the Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio. The Northwest Land Ordinance mandated that before statehood, a territory must be governed by five presidentially-appointed federal officials: a governor, a secretary, and three judges. Blount, as the original “wheeling and dealing, land speculating, sharp-nosed manipulator, politician and financier” knew how to attain what he wanted, usually employing “the shortest route.”[14] Blount seemingly grabbed the governorship (along with the title of Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Department) easily from President Washington by convincing a number of influential associates to intercede with the president on his behalf. Once his commission was confirmed, Blount fully utilized his authority to build a network of personal obligation and influence throughout the territory with officials including justices, sheriffs, constables, clerks, registrars, and every militia officer below the rank of general. He reportedly boasted that “no lawyer could plead in the Southwest Territory without a license from him.”[15] The position evidently pleased the family and its vital land investments. To his brother, John Gray Blount, Blount openly admitted, “I thank you for your Congratulations on my Appointment and I rejoice at it myself for I think it of great Importance to our Western Speculations.”[16] Blount’s various appointments guaranteed him absolute control of his domain. He was also a “shrewd politician who knew all of the clever little devices for retaining the loyalty and support of his appointees; and he knew particularly how to play upon the vanities of his superiors.”[17]

Washington was no fool when it came to the intrigues of the Blount family and the western territories in general. The president correctly analyzed the regional political situation as delicate, and was “anxious to conciliate frontier leaders so that no new separatist movement” would split territories from the control of the Federal government.[18] Prior to ratification of the Constitution, James Wilkinson participated with many local veterans in the so-called 1788 “Spanish Conspiracy” with a goal of establishing an independent western republic allied with Spain, going so far as swearing allegiance to the Spanish Crown.[19] Washington, always the ultimate strategist, undoubtedly knew of Blount and his family’s dubious business dealings and carefully planned his political movements. To counter the corruptive regional influence of Blount, Washington commissioned Wilkinson as a regular army brigadier general, countering Blount’s power while concurrently maintaining Wilkinson under observation. Washington considered this as a long-term stratagem to solve or reduce his western problems by establishing “such a system of national policy as shall be mutually advantageous to all parts of the American republic.”[20]

Although the Blount family used every opportunity to enrich themselves using Blount’s position, Blount functioned in a strong manner to carry out the orders arriving from the capital in Philadelphia. As a demonstration of his executive authority, he issued a proclamation to the residents of the Southwest Territory:

Whereas I have received certain information, that a number of disorderly, ill disposed persons, are about to collect themselves together, with an intention to go to the Upper Cherokee towns, on the Tennessee to destroy the same, and kill the inhabitants thereof, regardless of law, human and divine, and subversion of the peace of the Government.

Now I, the said William Blount, Governor in and over the said territory, do hereby command and require the above described persons, and every one of them, immediately to desist from such their intention, and to disperse and retire peaceably, to their respected abodes, within one hour from the moment of promulgation of this proclamation.[21]

The Native American’s military prowess in the Southwest Territory was never a cause for celebration by Blount or the federal government. Depending on inexperienced militias, combat with the Native American tribes had proven disastrous for the country. Military defeats made Blount’s policies, in his dual role as Superintendent of Indian Affairs and Governor, precarious. By the time of his 1793 Proclamation, Blount, and thousands living in the territory, concluded that the federal government “was not in a position to be realistic about, even if it had accurately been informed of, actual conditions on the Southwestern frontier.”[22] To Blount and other influential territorial individuals the “federal government in Philadelphia was a remote, impersonal operation that not only failed to assist the beleaguered westerners,” but it also consistently “disgraced itself abroad by consenting to treaties that negated American commercial rights or land claims” with an ultimate result of “humiliating a proud and free people.”[23] Blount’s political alliances shifted to the expanding Republican Party under Thomas Jefferson, but his primary loyalties never wavered from his family and their quest for wealth. Captivated by accounts of gigantic sales of western land to European investors by major Eastern speculators, the Blounts felt compelled to re-affirm their efforts “to acquire fantastic amounts of acreage for the purpose of overseas disposal.”[24]

The national government was able to successfully “turn the corner” in the Northwest by applying a newly rejuvenated military. By the mid-1790s, a well-organized and well-equipped Legion of the United States had crushed a Native American coalition. With the Northwest secured, the national government laid the foundations for law, order, and rapid commercial development in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Unlike the Southwest Territory, the investment of resources in the Northwest Territory had completely displayed not only the power of the national government, but also its “value.” The cost was the ill-will and alienation of Blount and his constituents who felt alienated and left out.[25]

Countless stories of Southwest territorial schemes, intrigues, and designs had started almost immediately following America’s independence. While details varied from scheme to scheme, “the common theme was the aggrandizement of the Southwest, either at the expense of one of the contiguous powers (including the United States), or with the help of one of the contiguous powers, or both.”[26] Frontiersmen, Eastern investors, and foreign opportunists saw this region as a place for riches and subsequent societal advancement. Blount was, in this respect, no different from many others. From the various plots, conspiracies and general discord in the region, European colonial powers stood to benefit with opportunities to expand or better secure their empires. This was especially true for the Spanish Crown, which was heavily involved in the region with their crucial settlement of New Orleans serving as a lynchpin on the strategic Mississippi River. Jefferson’s views on this key settlement were, “There is on the globe one single spot the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which three-eighths of our territory must pass to Market.”[27] Many Americans worried that a Franco-Spanish alliance could result in Spain’s ceding Louisiana to its partner. The exchange of declining Spanish reign for vibrant French authority filled with revolutionary fervor concerned Blount and the majority of residents in the Southwest: their trade, travel, and property rights—the foundations of their wealth and prosperity—were in grave jeopardy. Since the spring of 1796, Federalist leaders hypothesized that a secret clause had been inserted into the 1795 Peace of Basel which promised the cession of Louisiana to revolutionary France. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering commented,

We have often heard that the French government contemplated repossession of Louisiana; and it has been conjectured that in their negotiations with Spain the cession of Louisiana & the Floridas may have been agreed on. You will see all the mischief to be apprehended in such an event. The Spaniards will certainly be more safe, quiet and useful neighbors. For her own sake Spain should absolutely refuse to make these cessions.[28]

As a result of regional and national reactions to these real and imagined geopolitical changes, Congress passed a deterrent, to prevent any hot-headed reactions that could have dramatic international repercussions, known as the Neutrality Act of 1794, stipulating that any person organizing a military expedition within the United States territory aimed at a foreign domination was guilty of a high misdemeanor.[29] This act, which carried a maximum penalty of three years imprisonment and a three thousand dollar fine, soon impacted the investigations of William Blount.

The Blount Conspiracy originated with John Chisholm, a former American Loyalist who served as a British soldier; the nebulous plot centered on seizing the remains of Spain’s decaying Southwest American Empire, with the support of the British government. This requested support was in the form of warships and military supplies; the project would be aided by Blount’s sympathetic Native American allies. The reward for Great Britain’s actions would be the transfer of the seized land’s title to the British Crown. In late 1796 Chisholm, a confidant of Blount who detested the Spanish because of his imprisonment in Pensacola, approached British Minister Robert Liston in Philadelphia with his grand aspirations, primarily an assault on Spanish West Florida. Although Liston did not consent to endorse this ill-counseled venture, he did little or nothing to dissuade the “hotheaded” Chisholm.[30] By the time Blount entered the fray with his add-on project using the Native Americans, Liston had already informed his London superiors that over fifteen hundred whites, “principally British Subjects, attached to their Country and their Sovereign” were “ready to enter into a plan for the Recovery of the Floridas to Great Britain” but needed warships, supplies, and commissions.[31] Blount sounded out his regional cohorts with his grand plan which was “on a much larger Scale” than the one first proposed by Chisholm. Basically, there would be a three-pronged offensive on Spain’s Southwest empire: the first thrust would utilize men “collected on the Frontiers of New York and Pensylvania” instructed to “attack New Madrid [in present-day Missouri], leave a Garrison in it, and proceed to the Head of the Red River and take possession of the Silver Mines;” the second attack, commanded personally by Blount, was to use men from Tennessee and Kentucky, “with those of the Natchez and Choctaws” to seize New Orleans; and the last, under Chisholm, consisting “of the Cherokees and the Creeks with the white men of Florida” would take Pensacola.[32] In return for its support, Britain was offered the seized territory and New Orleans would be declared a free port open for unrestricted use by interests such as those of Blount and his confederates.

It is ironic that Blount himself provided the crucial piece of incriminating evidence proving that there was truth to the conspiratorial rumors that spread throughout the Territory and the eastern United States. President Adams and the members of his administration heard these same tales. To verify information, a presidential summons was issued which ultimately deprived Blount of meeting personally with his frontier supporters; he made the ill-fated choice of committing his thoughts and instructions on his plan to paper. On April 21, 1797 he wrote a detailed letter to longtime friend and Indian interpreter James Carey at Col. James King’s Iron Works in Tennessee. Blount confessed, “Among other things I wished to have seen you about, was the business Captain Chesholm mentioned to the British Minister last Winter in Philadelphia.” He felt that “the plan then talked of will be attempted this fall; and if it is attempted, it will be in a much larger way than then talked of; and if the Indians act their part, I have no doubt but it will succeed.” Blount provided his future prosecutors with the confession they required for “high crimes and misdemeanors” with his own ill-conceived words: “A man of consequence has gone to England about the business, and if he makes the arrangements as he expects, I shall myself have a hand in the business, and probably shall be at the head of the business on the part of the British.” He admitted to Carey “that it was not yet certain that the plan will be attempted; yet, you will do well to keep things in a proper train of action, in case it should be attempted, and to do so will require all of your management,” Carey ultimately did not heed Blount’s cautious warning that “he must take care, in whatever you say to Rogers, or any body else, not to let the plan be discovered by Hawkins, Dinsmore, Byers, or any other person in the interest of the United States or Spain.”[33]

Blount realized the seriousness of the incriminating letter, but felt that Carey could be completely trusted in both his loyalty and judgment. He advised Carey “to take care of yourself. I have now to tell you to take care of me too; for a discovery of the plan would prevent the success and much injure all the parties concerned.”[34] Blount, always the schemer, believed he had a fall-back plan if his enterprise was unearthed. He felt that culpability, especially in regard to the use of and relations with the Native Americans, could be taken off of him and heaped “upon the late President, and as he is now out of office, it will be of no consequence how much the Indians blame him” for all of these actions.[35]

Blount’s trust in Carey was poorly placed—Carey gave the letter to a government agent, who passed it up the chain of command. It reached Secretary of State Pickering in the middle of June, and then President Adams. News of the “extraordinary letter of Governor Blounts to Cary” quickly made the rounds throughout the government.[36]

In politics, his personal life and in all affairs, President Adams maintained a reputation of independent action. Concerning Blount, Adams took evils, such as political opportunism and factionalism, literally, and with him they amounted “to an obsession.” Upon his inauguration to the presidency, Adams brought a long public career, “devoid of Political experience, a detestation of political parties—Federalist and Republican alike—and a deep suspicion of the great European powers.”[37] These are the views that Adams brought to the table as the Blount Conspiracy quickly unfolded during the beginning of his administration.

Secretary of State Pickering investigated British involvement with Blount by quizzing the Minister Robert Liston. Liston, who by now had learned that the British Foreign Secretary Lord Grenville had declined any support, could truthfully deny his government’s involvement by providing an official dispatch attesting to this fact—although he may have been vague as to what the British actually knew of the conspiracy and when they knew it.[38] Liston may have stretched the truth when he said that he had always been unsympathetic to the plot, but that the importance of the proposals made it impossible to reject them on his own authority.[39]

Former President Washington was clearly angered and he urged that the appropriate action be taken:

The interscepted letter, of which you were at the trouble to send me a copy, if genuine is really an abomination; disgraceful to the Author; and to be regretted, that among us, a man in high trust, and a responsible station, should be found, so debased in his principles as to write it . . . I hope the original letter, if it carries the marks of genuineness, has been carefully preserved and forwarded to the proper departments, that the person guilty of such atrocious conduct may be held to public view in the light he ought to be considered by every honest man, & friend to his Ctry.”[40]

Washington’s letter undoubtedly portrayed the deep emotions of many Americans with the feelings of betrayal as Americans rather than as members of one particular political party or another.

The wheels of justice began to turn quickly throughout the remainder of June. Adams queried Attorney General Charles Lee for his official opinion on the Blount matter as the facts quickly began to solidify. Lee requested assistance from the United States attorney in Philadelphia, William Rawle, and prominent Federalist William Lewis. On June 22 they unanimously agreed that Blount’s infamous letter was evidence of a crime—specifically, a misdemeanor—and that Blount was subject to impeachment for this offensive action.[41] The sword hung over the unaware Blount for nearly two weeks until his letter was presented to the President of the Senate, Thomas Jefferson, on July 3 and was read before the body with Blount absent. As the Senate chamber predictably exploded in an uproar, Blount entered and was treated to another reading of his document with Jefferson seemingly uncomfortably pressing if the senator was indeed the letter’s author.[42] Blount admitted to writing a letter on or about that date to James Carey, but he stalled the proceedings by saying he was unable to ascertain if the letter read to the Senate was a correct copy or not and requested a day, and a copy of the Senate’s document, to check his personal files. With his request granted, Blount had some breathing space and departed the chamber. Simultaneously, downstairs in Philadelphia’s Congress hall, the House of Representatives immediately formed a committee to investigate the entire matter. Initially the affair was kept confidential, but the patience of the Senate soon expired as Blount continued to stall and they formed their own investigating committee. When Blount was requested by Jefferson to appear before the Senate, it was discovered that he had fled Philadelphia.

For the next eighteen months, Blount and his actions consumed the Congress. Blount had quickly reconsidered his actions and returned to Philadelphia within a day to personally witness the first practical Congressional impeachment discussions. His primary issues settled on whether civil officers were subject to impeachment, and if so whether a senator was a civil officer. The dominant Federalists mainly took the Hamiltonian viewpoint that “all was granted except that which was denied” while the Republicans contended all to “be prohibited which was not expressly granted.”[43] Whether Blount’s reckless actions were private or public and if they were in any form related to duties as a federal senator required debate and scrutiny. Blount’s attitude and his brief flight from justice clearly won the majority of condemnation from both sides of the aisle and the principal questions centered on: (1) how to deal with him; (2) why an investigation was in order; (3) who should conduct it; and (4) when should it take place.[44] By July 6, Blount’s position was quickly failing as any attempts to delay the inevitable impeachment process had ended. During the investigative process, even with Blount going on the offensive with the hiring of two brilliant Philadelphia attorneys, the Senate had enough and decided, with a twenty-five to one vote, that Blount was unworthy to hold his seat. Blount’s situation went from bad to worse as he was impeached, expelled, and continued to face the prospects of a senatorial trial. He also confronted a criminal action in a Federal District court in Pennsylvania. Matters for Blount continued to be bleak as a misdemeanor charge for disturbing the peace and tranquility of the United States was instituted and that charges could be made by the Attorney General that Blount had violated the Neutrality Act, which would elevate this case to federal circuit court. Blount decided to cut and run to his sanctuary of Tennessee.

Blount’s flouting the national government’s authority by fleeing to Tennessee, and refusing to return to Philadelphia, was a challenge to Congress. He demonstrated the vulnerability of the national government, causing it embarrassment throughout the world. The Senate’s sergeant-at-arms reportedly could not get anyone in Knoxville to assist him in arresting Blount.[45] It is ironic that Blount triumphantly, in the eyes of his Southwestern supporters, managed to continually insult the honor and dignity of the United States whose governance he sought to establish and promote in Tennessee.

Blount’s deeds united, although briefly, many Congressmen of both parties.[46] They were furious with Blount’s flight as it virtually rendered the government impotent. Blount’s guilt was no longer a question for anyone; instead the question was “if the dignity of the government required him to be present for his trial in the Senate,” as the very honor of the country and the legitimacy of the Constitution had been wounded.[47] Congressmen maintained that to prosecute Blount in absentia was to declare the government’s defeat from the onset. On December 21, 1798, Congressman Robert Harper of South Carolina contended that Blount’s reputation, “a man’s dearest possession,” and that of the United States were both in jeopardy. He declared, “Ought the public to be suffered to see the foolish spectacle of the House of Representatives going up to the Senate from day to day, to try a man laughing at them in the State of Tennessee, or the District of Maine?”[48] After much debate, the majority of the House of Representatives voted to continue with the impeachment. In the Senate, the special topic was if a senator was an officer to the government and, therefore, subject to impeachment for his actions, the same worry as to the stateliness of the national government that had repeatedly materialized within its members’ debates. Senator James Bayard of Delaware asserted on January 3, 1799 that the subject of “impeachment . . . is not so much designed to punish an offender as to secure the State.”[49]

Blount escaped further impeachment prosecution on a technicality that he was no longer an actively serving federal senator due to his expulsion. Although he had provided political fodder for both the Federalist and Republican Parties, the episode received a fraction of the political animosity, with its charges and counter-charges, that other individuals experienced. Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott felt that, “Had the Senator from Tennessee been a member of the federal party, much capital would doubtless been made out of his misconduct, as corroborating the standing charges of British influence. He was, however, a ‘republican;’ one whose vote had always been found, on party questions, among the opponents of the administration.”[50]

The repercussions of Blount’s exploits and the impeachment hearings did not fade upon his passing. Blount’s name, like Aaron’s Burr’s or Benedict Arnold’s, entered the American political lexicon as synonymous with words for illicit plots and intrigues. In the nineteenth century Thomas Paine, in a letter to Jefferson requesting logistical data prior to the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory, asked if New Jersey Congressman Jonathan Drayton was “an Agent for the British as Blount was said to be?”[51] Although Paine’s comments were somewhat prejudicial, it is not an overstatement to say that the Anglo-American relationship during this period of covert operations was “close and respectful, if not always open and ingenuous,” as British Prime Minister Pitt’s government quickly renounced Robert Liston’s only major American transgression.[52]

Although Blount’s conspiracy was soon dwarfed by increasingly larger events. The majority of John Adams’ administration was engrossed, to a degree unequaled in the majority of American presidencies, with a single ongoing problem: a crisis in foreign relationships. In his famous correspondence with Jefferson, Adams wondered about, “The escape of Governor Blount” and that there was “something in this Country too deep for me to sound.” He had wondered, “Is a President of the United States to be Subject to a private Action of every Individual?”[53] Adams seemed always to believe that “Blount was able to escape with impunity.” In reviewing propositions for amending the Constitution in 1808, he commented that it was “fully proven” that Blount had tried “to dismember the empire, and carry of an immense portion of it to a foreign domination.” He bemoaned that for the legal process, “much time was consumed, and how much debate excited, before that important subject could be decided! and then the accused person, with all of the guilt upon his head” had avoided further prosecution.[54] Others in the government agreed with Adams that, “This affair of Mr. Blount, has already been productive of very great injury to the United States.” South Carolina Congressman Robert Goodloe Harper speculated that the Spanish had “been long apprised” of Blount’s military attempts on their territory and “it furnished them with a reason or pretext at least, for delaying to deliver up their posts on the Mississippi” or to delay executing a treaty with the United States.[55]

The exposure of Blount’s illegal plans did not lessen his lust for more land or power. Upon his return to Tennessee in 1798, he received almost a hero’s welcome and was subsequently elected to the state’s senate and to the speakership, the state’s second highest office. Blount may have achieved further political preferment within his home state, his and his family’s vast fortune was substantially reduced. He died on March 21, 1800 at the age of fifty, reportedly of chills and a stroke. His impeachment proved that the new Federal Constitution could successfully function in a civilized manner (under Article Two Section 4) and that a nation could be effectively governed by laws even when threatened by potentially damaging crimes.

[1]George Washington to the Secretary of War, Timothy Pickering, August 14, 1797 quoted in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, 39 vols. (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1931-44), 36: 8.

[2]John Adams in the Review of the Propositions for Amending the Constitution submitted by Mr. Hillhouse to the Senate of the United States in 1808quoted in Charles Francis Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States with a Life of the Author, 10. vols. (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850-56), 2: 536.

[3]Buckner F. Melton, Jr., The First Impeachment: The Constitution’s Framers and the Case of Senator William Blount (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1998), 63.

[4]John C. Miller, The Federalist Era 1789-1801 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960), 189.

[5]William H. Masterson, William Blount (New York: Greenwood Press, 1969), 349.

[6]Arthur Preston Whitaker, The Mississippi Question 1795-1803: A Study in Trade, Politics, and Diplomacy (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), 106-107.

[7]Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert, eds., Launching the “Extended Republic”: The Federalist Era (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996). 157.

[8]Marcus J. Wright, Some Account of the Life and Services of William Blount (Washington: E.J. Gray, 1884), 3.

[9]Abigail Adams to Mary Smith Cranch, July 6, 1797 in Stewart Mitchell, ed., New Letters of Abigail Adams 1788-1801 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1947), 100.

[10]Masterson, William Blount, 7.

[11]Ibid, 40-41. The election reportedly was fierce and violent even by eighteenth century standards in North Carolina. Despite that both candidates countenanced illicit practices, the sheriff’s decisions on eligibility matters were erratic and the ballot box (referred to as a “Tin Cannister without a Top”) was unsealed and unguarded The result was that Spraight was declared the victor, but Blount formally protested; the committee on privileges and elections declared the entire election illegal and the House of Commons subsequently set it aside and neither party was re-elected in time to take his seat during that session.

[12]Melton, First Impeachment, 63.

[13]James Madison, Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1966), 657.

[14]Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767-1821, 2 vols. (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 1: 51.

[16]William Blount to John Gray Blount, 26 June 1790 in Alice Barnwell Keith, ed., The John Gray Blount Papers 1764-1795, 2 vols. (Raleigh, NC: State Department of Archives and History, 1952-59), 2: 67.

[17]Remini, Andrew Jackson, 52.

[18]James Thomas Flexner, George Washington and the New Nation 1783-1793 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1969), 267.

[19]A.P. Whitaker, “Spanish Intrigues in the Old Southwest: An Episode 1788-89,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 12, No. 2 (September 1925), 155-176; Melton, First Impeachment, 80-84.

[20]George Washington to Harry Innes, March 2, 1789 in Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington,30: 215.

[21]Henry Knox to Tobias Lear, February 28, 1793 with William Blount’s January 28, 1793 Proclamation in Philander D. Chase, et al, The Papers of George Washington –Presidential Series, 12 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1989-2005), 12: 2n.

[22]Masterson, William Blount., 217.

[23]Remini, Andrew Jackson, 80.

[25]Hoffman & Albert, Extended Republic, 171.

[26]Melton, First Impeachment, 80.

[27]Thomas Jefferson to Robert Livingston, April 18, 1802 in Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896), 143-47.

[28]The Peace of Basel consisted of three peace treaties in which France made peace with Prussia and with Spain ending the War of the Pyrenees. The result was that revolutionary France emerged as a major European power; Timothy Pickering to Rufus King, February 15, 1797 quoted in Alexander DeConde, Entangling Alliance: Politics &Diplomacy under George Washington (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1958), 449.

[29]Melton, First Impeachment, 86.

[30]Hoffman and Albert, Extended Republic, 160.

[31]Robert Liston to Lord Grenville, January 25, 1797 in Frederick Jackson Turner, ed., “Documents on the Blount Conspiracy, 1793-1797,” American Historical Review, Vol. 10, No. 3 (April 1905), 576-577.

[32]Declaration of John D. Chisholm to Rufus King, November 29, 1797 in Turner, “Documents,” 599-600.

[33]William Blount to James Carey, April 21, 1797 in the Journal of the Senate, July 8, 1797 in Martin P. Claussen, ed.,The Journal of the Senate including the Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate-Fifth Congress, First Session-John Adams Administration, 2 Vols.(Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, Inc., 1977), 1: 105-108. Native American interpreter John Rogers, Former Congressman Benjamin Hawkins and the new Indian Superintendent, Silas Dinsmore, and Federal Government sutler/agent James Byers.

[36]David Henley to George Washington, June 11, 1797 in Dorothy Twohig., et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington-Retirement Series, 4 Vols. (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1998-99), 1: 179.

[37]Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 534-539.

[38]Melton, First Impeachment, 106.

[39]Gerald H. Clarfield, Timothy Pickering and American Diplomacy (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1969), 132.

[40]George Washington to David Henley, July 3, 1797 in Ibid, 229-230.

[41]Melton, First Impeachment, 106.

[42]Mitchell, Abigail Adams, 100.

[43]Melton, First Impeachment, 115.

[45]Hoffman and Albert, Extended Republic, 182.

[46]The 5th United States Congress was comprised of ten Republicans and twenty-two Federalists in the Senate and forty-nine Republicans and fifty-seven Federalists in the House of Representatives.

[47]Hoffman and Albert, Extended Republic, 82.

[48]Robert Goodloe Harper in Annals of Congress, 5th Congress, 3rd Session, 2478.

[49]James A. Bayard, Annals of Congress., 5th Congress, 3rd Session, 2251.

[50]George Gibbs, Memoirs of the Administrations of Washington and John Adams, Edited from the Papers of Oliver Wolcott, Secretary of the Treasury, 2 Vols. (New York: W. Van Norton, 1846), 2: 552

[51]Thomas Paine to Thomas Jefferson, August 2, 1803 in Philip S. Foner, ed., The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 2 Vols. (New York: Citadel Press, 1969), 2: 1442. Congressman Drayton visited New Orleans in July of 1803 and consequently favored the United States purchase of the Louisiana Territory following his return to the capital. He was later indicted for participation in Burr’s conspiracy.

[52]Bradford Perkins, The First Rapprochement: England and the United States 1795-1805 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1955), 99.

[53]John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, May 1, 1812 in Lester J. Cappon, The Adams-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and Abigail and John Adams (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987). Almost always a highly moralistic and ethical individual, Adams furthered questioned whether this type of supposed responsibility would “introduce the Axiom that a President can do no wrong; or another equally curious that a President can do no right.”

[54]John Adams in Adams, Works of John Adam, 6: 536-537.

[55]Robert Goodloe Harper, July 24, 1797 in Noble E. Cunningham, ed., Circular Letters of Congressman to Their Constituents 1789-1829, 3 Vols. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 1: 103.

Recent Articles

John Dickinson and His Letters

North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution

The Two “Empires of Liberty:” The Fascinating Story of an American Phrase

Recent Comments

Ms. Spiegel, This is so beautifully done, IMHO, that I would love...

From your review, the naval and military professors produced an excellent primer...

Thank you, D Malcolm and good luck on your dissertation. In addition...