The war for all practical purposes was over when hostilities ended with a cease fire negotiated by the Americans, British, French, and Spanish in January 1783.[1] In New York, on June 19, British Brig. Gen. Samuel Birch wrote Commander-in-Chief Sir Guy Carleton that he had failed in his mission to locate and apprehend Capt. Cornelius Hatfield.[2] Carleton promised to comply with New Jersey Gov. William Livingston’s request that an “immediate search to be made for Cornelius Hatfield, that effectual justice may be done.”[3] Hatfield was usually seen around Gen. Cortlandt Skinner’s headquarters on Staten Island, a place that served as an island fortress garrisoned by Loyalist battalions.[4] General Birch had “taken much pains to discover if Hatfield was in the garrison and the only information I have been able to obtain, is, that he embarked privately on a schooner, and sailed two or three days before the last fleet for Nova Scotia.”[5]

The man being sought was the Loyalist partisan Cornelius Hatfield, an articulate and intelligent man with boundless energy, and skill in violence. The only description of Hatfield’s appearance that exists is from an unsourced nineteenth-century history that says “he was fine looking man, with dark hair, fair skin, and fine, ivory-like teeth,” and that he received a “fine education. He was very active and strong.”[6] A Loyalist who knew him said that “Hatfield was a very zealous Loyalist . . . but a loose, drinking sort of man and not of the coolest sense.”[7] Hatfield’s bravery was never in question, as demonstrated when he and about a dozen men under his leadership captured a twelve-gun sloop while under a hail of musket and artillery fire from a Rebel picket.[8] A Patriot spy in New York said that Hatfield “swears he will hang every one of those committeeman and others that have sworn the King and Congress and then taken arms against the King.”[9]

People at the highest levels of the American Revolutionary government grew to fear Cornelius Hatfield. When it was learned that Hatfield left New York in a small schooner to bring dispatches to Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in September 1781, Continental Congress President Thomas McKean warned Delaware President Caesar Rodney that if “Cornelius Hatfield should be apprehended, I am to request that he may be securely confined and guarded.”[10]

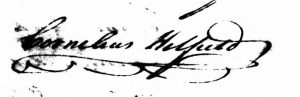

A native of Elizabethtown, New Jersey, Cornelius Hatfield was commissioned a captain by Gen. Henry Clinton on February 19, 1779, leading an independent company of Loyalists that he described as partisans.[11] At this time, New York was still the nerve center of military operations in North America despite the conflict’s shift to the Southern colonies and West Indies. Hatfield’s career was most prolific in “an odd sort of battleground, on which vengeful partisans warred while their respectful armies remained essentially above the fray,” according to historian Thomas Allen. Hatfield was considered a “Refugee” whom Allen defines as a displaced class of Tories that occasionally returned to their homelands as raiders.[12]

The officers who employed Hatfield swore on their reputations that he was courageous and “zealous” in all his missions. Loyalist Gen. Cortlandt Skinner said of Hatfield, “I have a very high sense of his merit and services as a brave partisan and steady Loyalist.”[13] In addition to valor, his superiors defined as virtue his contentment to stare up at the rungs of promotion as long as he was able to strike at Britain’s enemies. Lt. Gen. James Robertson declared that Hatfield “asked for no office, or solicited any reward.”[14] Skinner said “I have several times offered him money for his services but he always refused it, declaring he wished for nothing more that the restoration of government.”[15] General Clinton endorsed his subordinates’ opinions of Hatfield.[16]

Elizabethtown was the strategically important “gateway to New Jersey and Philadelphia.” The town was fortified and garrisoned by the Patriots early in the war. Staten Island, occupied by British forces in the summer of 1776, was only several hundred feet across the Arthur Kill from Elizabethtown’s main landing.[17] That December Hatfield started providing the Loyalists on Staten Island with information during the British invasion of Northern New Jersey.[18]

After northern New Jersey was vacated by the British, Staten Island remained under occupation. Hatfield started providing General Skinner with intelligence face-to-face in addition to the occasional ink and paper in 1777. The messaging became more sophisticated as Hatfield and Skinner worked out a signal system. Skinner said that Hatfield provided him with “the movements of the Rebel Army in the Jerseys and settled signals with me to be made from his Father’s house, in sight of Staten Island that I might know of the arrival of Troops in Elizabeth Town, their movements towards Sandy Hook, or attempts on Staten Island.”[19] Hatfield had his own parcel but also farmed the land of his father Cornelius Hatfield, Sr. which was in close proximity to the shore at Halstead’s Point.[20]

The Patriots of Elizabethtown started to suspect that Cornelius Hatfield was assisting the British.[21] The tipping point for the Patriots came when Hatfield journeyed south to Middletown (present-day Mattawan) and “was apprehended under suspicion that we were going to the enemy with a vessel he was loading at Middle Town.” Hatfield was arrested while loading a boat with substantial quantities of provisions including Iron. Patriots concurrently intercepted a letter directing a “C.H.” to liaise with a “J.H.” of an armed escort ship off Sandy Hook for the purposes of transporting the cargo to Virginia. The letter also “contains general other matters that looks unfavorable to Hetfield.”[22]

Gen. William Maxwell, the military authority in Elizabethtown during the winter of 1778-1779, was told by Gen. George Washington that “the principal object of your position is to prevent the Enemy stationed upon Staten Island from making incursions upon the main and also to prevent any traffic between them and the inhabitants.”[23] Maxwell was determined to fulfill his mission and therefore placed Hatfield in the Elizabethtown provost.

A writ of habeas corpus dated December 17, 1778 from the New Jersey Supreme Court had been obtained by advocates for Hatfield, but was refused on several occasions by Maxwell.[24] An effort to turn Cornelius Hatfield over to the civilian authorities was persistent and most likely driven by Hatfield’s father Cornelius, Sr., a very well respected, wealthy, and influential man.[25] Elizabethtown at this time was populated with 1,200 people mostly descended from the original town “Associates” who had carved-out the first English-speaking settlement of New Jersey.[26] A late eighteenth century map of the town and environs reveals a quilt of properties owned by descendants of the Associates.[27] Decades of the cementing influences of intermarriage bound the community together. The timing of the cargo shipment and the “C.H.” letter implicating Hatfield were considered by his advocates to be “circumstantial.”

Maxwell, battlefield experienced, refused several attempts to honor Hatfield’s writ of habeas corpus. The general fanned the flames of discord by hurling “several undeserved insults” at one advocate serving the writ,while another received “reproachful language” and was grabbed by “his neck or hair and shoved” out of his quarters. Hatfield’s advocates wrote Continental Congress President John Jay imploring that Hatfield should have a civil trial, and requesting a formal reprimand of Maxwell.[28]

Washington ordered Maxwell to turn Hatfield over to the civilian authorities, but it was too late.[29] On January 9, 1779, Governor Livingston informed Washington that Cornelius Hatfield had escaped. Livingston expressed good riddance and tried to provide a silver lining: “While the Magistrates had the charges against Hetfield under consideration, he made his escape from the guard; and unless his treason (of which I have no doubt) could be more clearly proved than I imagine it would have been upon his trial, it is perhaps best for the public, that he has been thus driven to take sanctuary with the enemy where I believe he can do us less mischief.”[30] General Skinner was on Staten Island waiting with open arms and said that as soon as Hatfield escaped “he joined me and immediately commenced an active partisan.”[31]

Hatfield’s first large scale raid serving as a guide for the British occurred a few weeks after he received his commission in January 1779. With 1,000 British troops he landed in New Jersey near DeHart’s Point.[32] General Clinton ordered the raid because “I was tempted by the uncommon mildness of the season to beat up the enemy’s quarters” and “surprise one of their brigades that lay at Elizabeth Town.”[33] Between 2 and 3am the alarm sounded and the “Whig”-leaning townsfolk hid on the far western outskirts of town. Some of the British troops split from the main group and headed toward Governor Livingston’s home a mile west of town, but the governor was away on business and his family had received warning and fled.

When it was all over, three plumes of smoke billowed into the night sky marking the locations of a flaming blacksmith shop, soldier’s barracks, and academy. Maxwell’s militia didn’t start to make a defense until the British were marching eastward to their waiting craft which were accompanied by a handful of gunboats lobbing ordinance at the pursuing militia.[34] General Clinton denied that the purpose of the raid was the capture Livingston in a reply to a letter sent by the governor complaining of what he deemed “dark proceedings.”[35]

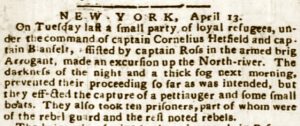

The summer after Hatfield’s commission in 1779 started off on a high note for the partisan captain. On an evening in June, Hatfield with five of his men crossed over to Elizabethtown and proceeded to the residence of Lt. John Haviland of the Essex County militia. Haviland was captured in the dead of night, transported to New York and imprisoned on Long Island.[36] The Loyalist newspapers reported these types of captures with jollity. The New York Gazette commented on a different headhunting raid: “Yesterday Capt. Cornelius Hatfield, with adroitness peculiar to himself, after an incursion upon the Jonathans in Jersey, brought off a lieutenant and 5 or 6 others, of which we shall give more particulars, when our sprightly partisan arrives in town, and makes his report.”[37]

Hatfield claimed two years after the war that he “captured nearly three hundred officers of rank and soldiers, the chief part of which were at different times exchanged for British of the same rank.”[38] The capture of Col. Matthias Ogden and Capt. Jonathan Dayton in November 1780 was his most significant haul. Hatfield learned from one his contacts in Elizabethtown that Ogden and Dayton were staying the evening in Connecticut Farms, about four miles away. This was too great an opportunity to pass up—both Ogden and Dayton were high-ranking officers and influential citizens of Elizabethtown. “With only two or three of his party, he made a circuit of many miles and brought off a rebel Colonel and Captain.”[39] Hatfield and his Refugees found the officers in Connecticut Farms “horizontal, Cheek by Jowl” as a Loyalist newspaper gloated.[40] No fish was too big for Hatfield to attempt to catch, not even the enemy’s commander-in-chief. Hatfield hatched a plan to capture General Washington who was staying at a mansion away from the main Continental Army encampment at Morristown, and the British army staged a major expedition to effect his plan. General Skinner wrote that the “troops marched to make the attempt but were prevented by a severe fall of snow, otherwise in all probability he would have succeeded.”[41]

General Skinner stated that Hatfield “was well acquainted with the creeks and inlets into New Jersey and kept a good correspondence with his friends” and “always procured of the enemy’s strength and situation, and almost every day informed me of the placing of their sentinels and by that means he has often gone at my request into Elizabeth Town and brought off particular people.”[42] Hatfield had miles of tall marsh-grassed coastline to conceal his landings. Elizabethtown had three major landing points on the coast facing Staten Island: DeHart’s Point to the North; Elizabethtown Point in the Center (one mile from town, the main road ran there to the west); and the more preferable Halstead’s Point to the south.[43]

Hatfield and his partisans using the cover of darkness attacked small Rebel patrols on the roads, and sentinels at the landings and homes of the inhabitants. Tory sympathizers provided Hatfield with intelligence and their homes served as sanctuaries. The sense of surveillance was so apparent to the locals that one of Hatfield’s neighbors told Connecticut soldier Joseph Plumb Martin “they know your situation better than you do yourselves.” Martin said that “with all the vigilance we could exercise, we could hardly escape being surprised and cut-off by the enemy. They exerted themselves more than common to take some of our guards, because we had challenged them to do it.”[44] A New Jersey militiaman recalled “skirmishes with small parties of the enemy . . . were very frequent, and occasionally men were killed on both sides. Cornelius Hatfield, a noted Tory and Refugee, gave us much trouble by taking off our sentries at night, and often killed our scouts, by intercepting them, knowing the ground.”[45]

In accordance with Gen. Guy Carleton’s promise to Governor Livingston in 1783, Hatfield was finally tracked down and incarcerated in New York’s Provost on August 15.[46] His arrest had nothing to do with his escape from rebel captivity or the raids he led as an officer. Back in June, Livingston wrote Carleton requesting “Hatfield to be apprehended and secured” in order to be brought into New Jersey to be tried for petty robbery.[47]

An affidavit including sworn testimony of the victim of Hatfield’s alleged crime landed on Carleton’s desk. An elderly man named Joseph DeHart, for whose family DeHart’s Point was named, testified to an Essex County judge that Cornelius Hatfield and a group came into his home on the evening May 6, 1783, and “seized the Deponent, one of who presented a Pistol at his Breast and ordered him to deliver up all he had in Money and swore by his maker that if he did not deliver up all his Silver and Gold, he would blow him through.” DeHart’s wife Elizabeth retrieved Joseph’s pocketbook, but the contents were considered wholly immaterial to the intruders and they tossed it aside. One of the intruders told DeHart that “they knew he was to have received of his Uncle Samuel, Twenty Pounds the day before, and said they were come for it, and ordered him to deliver it up.” DeHart claimed ignorance of the money and was unable to produce it, at which point the intruders left his home.[48]

On August 24, 1783, nine days into his imprisonment, Hatfield wrote a letter to General Carleton presenting his version of the events that had taken place at Joseph DeHart’s home:

My former residence, and that of my Friends is near the Complainant at Elizabeth town, and on the Night he charges me to have been at his House . . . I was in the country on a visit to see these Friends and on my return Home hearing a Noise at the House of the Complainant, I went to it from the Road and found that some Persons had been there and endeavored to frighten the Complainant who is a poor weak illiterate Man, easily imposed on. On my entering the House I made myself known the Complainant and advised him to go to Bed, and make himself easy as no Injury was intended him . . . He accordingly went to his Bed, and appeared happy that I interfered for his Relief. This is simply all the circumstances I am acquainted with relative to this Transaction.

Hatfield reasoned in his defense that it took a full month for the incident to be reported and escalated. The length of time allowed DeHart to be “urged to it by Persons who are inimical to me for my uniform opposition to Congressional Measure.” Hatfield called Joseph DeHart “of all men the most ignorant and does not understand the simplest English Term,” making him ripe for manipulation. He argued that it was not logical that Hatfield did not conceal his identity from DeHart, and he believed he was entitled to have DeHart testify in person. The letter to Carleton included an impassioned assessment of his own character:

During the whole progress of the late War I have been an active and zealous assertor of the King’s Cause and as such, been frequently employed in the most important enterprises . . . My character as a man of probity and no plunderer much less a robber is too firmly established.[49]

Hatfield’s detractors in Elizabethtown could refute him by pulling court records related to an incident in June 1778. Hatfield was indicted by the New Jersey Supreme Court for trespassing, assault, and theft of a sword from an Elizabethtown man named Jacob Foster. Also, though on the record long after the trial, a Newark man named Zopher Lyon claimed Hatfield robbed him of goods in 1780. Hatfield and his cousin John Smith Hatfield helped Lyon by piloting a large craft to New York to purchase “wares & merchandise.” Later, when Lyon and another man were moving the goods in a small boat along the Bergen Shore, they were boarded by “three men in disguise having their faces covered in black handkerchiefs.” One of the men put a pistol to Lyon’s chest and demanded the cargo. Lyon “verily believes the voice to have been the aforesaid Cornelius Hatfield.”[50]

In addition to his own personal plea Hatfield had witnesses, mostly from his own family and relatives, provide sworn statements for his defense.

The Revolutionary War participants of the Hatfields in Elizabethtown were the fourth and fifth generation grandchildren of Elizabethtown settlers Matthias and Maria Hatfield.[51] Joseph Plumb Martin said of the family: “There was a large number in this place and its vicinity by the name of Hetfield who were notorious rascals.”[52] When General Washington was asked permission that one of the “rascals” be allowed to come through the lines to visit his brother in Elizabethtown, the commander-in-chief replied: “From the information I have had of the character of this family of people—I am by no means satisfied that they would answer any valuable purposes if they were employed—and therefore I wish it to be declined.”[53]

A trio of Loyalist brothers, Abraham, Jacob, and James Hatfield, settled in Canada when the war ended.[54] There were the Tory brothers Job and John Smith Hatfield, the latter at Cornelius’ side more than any of his other cousins.[55] Cousin Abel Hatfield was suspected by members of the Rebel intelligence apparatus as being a part of the “perfidious treachery of that family” in the form of manipulating Patriot military officers with misinformation provided by General Skinner.[56]

The Hatfields did send soldiers into the field for the cause of American Independence. Job and John Smith Hatfield’s brother Morris fought for Independence with courage and distinction, suffering a severe wound.[57] Joseph Hatfield served in both the War of Independence and the War of 1812.[58] [59] One Hatfield was suspected of straddling both sides of the fence: Aaron’s brother Moses Hatfield—a major in the New York Militia who as a commissary for the army, was investigated for mismanagement and graft.[60] Treasonous suppositions from the highest levels including General Washington where strengthened when Moses was arrested for going into the British lines without a pass.[61]

Cornelius Hatfield himself was the middle-son of Cornelius Hatfield Senior and Abigail Price. Cornelius’s older brother Abner was recommended for a quartermaster’s position in December 1775 but there is scant evidence that this went through.[62] His younger brother Caleb appears to have not been actively involved in the war. Cornelius had twin sisters named Abigail and Joanna, the latter married to Patriot light horse captain John Blanchard.[63]

Appearing on Cornelius Hatfield’s behalf in 1783 were his sister Abigail, his cousins James, Job, John Smith Hatfield, and an unrelated partisan named Abraham Jones. All five simply reinforced Hatfield’s version of events—all were with him that night with the exception Abigail who claimed that she overheard DeHart’s wife Elizabeth state that her brother did visit the couple’s home that evening but that Cornelius was courteous and that legal authorities of Essex County were exaggerating events.[64] Separately, a lawyer named George Ross certified that “I have never heard or do I believe that Cornelius Hatfield junior ever made the practice of entering houses of people with a design to plunder, on the contrary . . . he has protected houses of individuals from robbery and plunder, several instances of which I was a witness.”[65] Cornelius Hatfield’s combined defense to General Carleton rested on the idea that Joseph DeHart was not intellectually sound and had been manipulated by leading Patriots. Hatfield’s exoneration, as he most likely saw it, rested on whether he would be brought to a civil trial in New Jersey or a court martial in New York.

Two events involving Cornelius Hatfield guaranteed that he would never receive a fair trial in New Jersey. In January 1780, Hatfield guided an expedition in-force over the iced-over Arthur Kill from Staten Island.[66] Lt. Col. Abraham Van Buskirk’s force consisted of 120 Royal Provincials supplemented by twelve dragoons and Hatfield’s partisans. The Loyalists crossed the ice at night and split into two divisions before entering Elizabethtown. What General Washington called “the late misfortune and disgrace at Elizabethtown” unfolded in the last few hours before midnight.

Van Buskirk’s raid achieved total surprise.[67] Before the raid, Captain Hatfield learned the positions of the Continentals and militia and formulated the plan of attack. General Skinner said “he pointed out to me the manner in which the Maryland Troops under Major Eccles, posted at Elizabeth Town could be surprised . . . Mr. Hatfield conducted with so much secrecy the post was completely surprised, the Major and all his officers made prisoner with about 80 of his troops and 40 militia without the loss of one life or even a shot being fired.”[68] The beautiful Presbyterian church “ornamented by a steeple” and the structure where “their pilgrim fathers had worshipped God” was put to the torch by Van Buskirk’s men. Cornelius Hatfield’s father was a member of the board of trustees of the church – and the land for which the church was built, a donation to the village by Hatfield’s great-grandfather Matthias.[69]

Cornelius Hatfield and his cousins were also mutually involved in a brutal incident that stirred passions in New Jersey long after the war. A Rahway man named Stephen Ball, a “London Trader,” was committing illicit commerce with the British when he brought his goods to Staten Island in February 1781. Refugees including the Hatfields seized Ball, brought him to Bergen Point and hung him. Sources primarily attribute the murder to John Smith Hatfield, though all the partisan Hatfields were placed there. The hanging was in retaliation for the execution of a Refugee by the Patriots. General Skinner refused to endorse the hanging.[70]

Fortunately for Hatfield, Carleton rebuffed Livingston and ordered a court martial in New York. Joseph DeHart was invited to testify under protection but failed to appear. British Lt. Col. James Gordon, president of the court, summarized the decision: “The Court having considered the charge brought against the prisoner in Cornelius Hatfield together with the several exhibits produced before them, no Viva Voce [oral] evidence, for or against him having appeared, is of the opinion that he is not guilty . . . that the prosecution is not only groundless but insidious and malicious in the utmost extreme.”[71]

During the war, Hatfield and his cousins had been divested of their property via formal inquisition and seizure by Essex County “for joining the army of the king of Great Britain, and other treasonable practices.”[72] Following the Treaty of Paris, the Hatfield Loyalists along with thousands of Americans headed north to New Brunswick, Canada, to start a new life. On November 21, 1784, Cornelius Hatfield experienced the only thing resembling a victory celebration. The former Partisan had the honor of piloting the sloop Ranger bringing the first lieutenant governor of New Brunswick across St. John’s Bay to his new province. The celebration of Gov. Thomas Carleton’s arrival “received an enthusiastic welcome from the Loyalists. A salute of seventeen guns was fired from the Lower Cove battery as the Ranger entered the harbor, and as he landed a similar salute was thundered from Fort Howe. A great concourse of the inhabitants received him with shouts of welcome The crowd gave him three cheers, and cries of ‘Long live our King and Governor.’”[73]

Unlike his cousins, Cornelius Hatfield chose the British capital as his new home, arriving in London in 1785. He immediately applied for relief from the Loyalist Claims Commission. The former Elizabethtown villager was living on the outskirts of London near the Marylebone Tollgate when he was granted a backdated temporary pension “for his uniform Loyalty and spirited exertions in favor of Government during the American War,” and was subsequently granted a military pension. Hatfield, from a town of 1,200, carved out a life in metropolitan London, and at forty years of age married forty-two-year-old Briton Joan Hinkley in December 1797 at the Old Church, St. Pancras, London. Curiously, the couple had three children by the time they married, and two more born “legitimately.”[74]

Cornelius Hatfield never gave up on his inheritance in his father’s will and his own son Sidney was named heir to the farm in Elizabethtown. Hatfield’s father Cornelius, Sr. passed away in 1795 and Hatfield made the first of two trips to the United States in 1796 which led to the accusation of armed robbery by Zopher Lyon.[75] His journey in 1807 resulted in a media sensation when the headline “A Tory caught” appeared in print throughout the United States.[76] Hatfield, who was called “an obnoxious refugee character” by The Vermont Journal, was in Newark when he was recognized and arrested for the hanging of the “London Trader” Stephen Ball. Hatfield had a team of three lawyers for his defense, and ironically, one them was Aaron Ogden—the younger brother of Col. Matthias Ogden whom he had captured at Connecticut Farms.[77] Hatfield was lucky in that the charges were dropped because the terms of the Treaty of Paris stipulated that British or American citizens could not be tried for actions committed during the war.[78]

During this 1807 visit, Essex County deed books show that “Captain Cornelius Hatfield of Great Britain (but at present in America)” sold fifteen and half acres of land to Caleb Halstead. Hatfield retained rights to a substantial portion of his father’s land because in 1829, his son and heir Sidney, sold the “farm formerly belonging formerly belonging to Cornelius Hetfield.” Sidney Hatfield, a painter, moved to the United States after Cornelius’s death in 1823. The son and heir of one of the most zealous Loyalist-Refugees of the Revolutionary War lived in New York for a time, then moved to Augusta, Georgia where he died in 1840.

Cornelius’s wife Joan passed away in March 1818 and was buried in St. James, Piccadilly.[79] His will, written on February 24, 1823, began, “I Cornelius Hatfield late of the borough of Elizabeth Town State of New Jersey America but now residing at No. 4 Great George Street Hempstead Road Parish of St. Pancras County of Middlesex Great Britain being sound in mind to make this my last Will & Testament.”[80] Capt. Cornelius Hatfield, Jr. passed away at sixty-eight years of age on August 13, 1823. He was buried four days later in the same cemetery as his wife in St. James, Piccadilly.[81]

[1]Treaty of Paris, 1783, U.S. Department of State Archive, 2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/ar/14313.htm.

[2]Samuel Birch to Sir Guy Carleton, June 23, 1783, Joanna McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, American Loyalist, Some of his story and an outline of his descendants (Blurb.com, 2016), 72, www.blurb.com/ebooks/pc62960b2818cd883ae0b.

[3]Guy Carleton to William Livingston, June 20, 1783, ibid., 71.

[4]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, November 19, 1785. Treasury, Class 1, Volume 634, folios, 182-183, Great Britain, The National Archives (TNA).

[5]Samuel Birch to Carleton, June 23, 1783, McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, 72.

[6]Richard Bayles, History of Richmond County, (Staten Island) New York, From is Discovery to the Present (New York: L.E. Preston & Co., 1887), 244.

[7]E. Alfred Jones, The Fighting Loyalists of New Jersey: Their Memorials, Petitions, and Claims, Etc. from English Records (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2008), 162.

[8]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/V634.

[9]William Maxwell to George Washington, April 27 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[10]Thomas McKean to Caesar Rodney, September 19, 1781, Letter Books of the President of Congress, 1775-1787, Roll 24, M247, 78-79.

[11]Memorial of Cornelius Hatfield to the Lord Sidney, London, January 2, 1786. T 1/634 folio 180, TNA.

[12]Thomas B. Allen, Tories: Fighting for the King in America’s First Civil War (New York: Harper, 2010), 301, 309, 311.

[13]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/V634.

[14]Certificate of Lt. Gen. James Robertson, London, November 25 1785. T 1/634 folio 183, TNA

[15]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/V634.

[16]Certificate of Lt. Gen. James Robertson, T 1/V634.

[17]Ernest L. Meyer, Map of Elizabeth Town, N.J. at the Time of the Revolutionary War, 1775-1783: Showing That Part of the Free Borough and Town of Elizabeth, Which is now the site of the City of Elizabeth (New York: J. Schedler, 1879).

[18]Memorial of Cornelius Hatfield to the Lord Sidney, T 1/634.

[19]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/V634.

[20]Meyer, Map of Elizabethtown.

[21]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/V634.

[22]Abraham Clark to John Jay, December 21, 1778, Papers of the Continental Congress, Letters Addressed to Congress 1775-1789, Roll 93, M247, p. 287-289 (POTCC).

[23]Washington to Maxwell, December 21, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[24]The Writ of Habeas Corpus, December 17, 1778, McKinnon. Cornelius HATFIELD, 26; Clark to Jay, December 21, 1778.

[25]Abraham Hatfield, Descendants of Matthias Hatfield (New York: New York Genealogical and Bibliographical Society, 1954), 21.

[26]Jean Rae Turner and Robert T. Koles, Elizabeth: The First Capital of New Jersey (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 7.

[27]Meyer, Map of Elizabethtown.

[28]Deposition of William Barnot, December 21, 1778, POTCC, Letters Addressed to Congress 1775-1789, Roll 93, M247, V5, 291-292. 297-298; Deposition of Garret Rapalje, Elizabethtown, December 21, 1778, POTCC, Letters Addressed to Congress 1775-1789, Roll 93, M247, V5, 293.

[29]Washington to Maxwell, December 20, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington

[30]Livingston to Washington, January 9, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[31]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/V634.

[32]Extract of a Letter from an officer at Elizabeth-Town, dated March 1, 1779, The New Jersey Gazette, in William Nelson ed., Archives of the State of New Jersey Second Series, vol. 3 (Trenton, NJ: John L. Murphy Publishing Co., 1906), 106-109 (ASNJ).

[33]Maxwell to Washington, Feb 27, 1779, FN 5, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[35]Maxwell to Washington, Feb 27, 1779.

[36]The New York Gazette: and the Weekly Mercury, June 14, 1779, ASNJ S2 V3: 441.; Lt. John Haviland, New Jersey. Complied Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War 1775-1785, M881, Roll 0645, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

[37]The New York Gazette: and the Weekly Mercury, November 27, 1780, ASNJ S2 V5: 127.

[38]Memorial of Cornelius Hatfield to the Lord Sidney, T 1/634.

[39]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/634.

[40]The Royal Gazette, November 8, 1780, ASNJ S2 V5: 104-106.

[41]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortland Skinner, T 1/634.

[43]Meyer, Map of Elizabethtown.

[44]Joseph Plumb Martin, Private Yankee Doodle: Being a Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary War Soldier, ed. George F. Scheer (Eastern Acorn Press, 1998), 176, 178.

[45]Pension Affidavit of Morris Aber, State of New Jersey, Morris County July 31, 1832. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, M804, Roll 0005, Pension File S.2525, NARA.

[46]The Royal Gazette, September 3, 1783, McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, 68.

[47]Livingston to Carleton, June 12, 1783, McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, 70.

[48]Affidavit of Joseph DeHart, June 5, 1783, ibid., 69.

[49]The Answer of Cornelius Hatfield, August 24, 1783, Cornelius HATFIELD, McKinnon, 78

[51]Hatfield, Descendants of Matthias Hatfield, 43, 76.

[52]Martin, Private Yankee Doodle, 180.

[53]Washington to Samuel Holden Parsons, December 23, 1779, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[54]Hatfield, Descendants of Matthias Hatfield, 90-98.

[56]John Vanderhovan to Washington, November 6, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[57]Hatfield, History of Elizabeth, 445; Hatfield, Descendants of Matthias Hatfield, 84-87.

[58]Hatfield, Descendants of Matthias Hatfield, 88-89.

[59]Ibid., 73-75; Pension Affidavit of Aaron Hatfield, State of New Jersey, Borough of Elizabethtown June 3, 1830. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, M804, Roll 1222, Pension File S.13.245, NARA.

[60]Board of War to Washington, January 5, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[61]William Burnet, Sr. to Washington, April 12, 1782, Founders Online, National Archives, Papers of George Washington.

[62]Lord Stirling to the President of Congress, December 3, 1775, American Archives: Consisting of a Collection Authentick Records, State Papers, Debates, and Letters, and Other Notices of Publick Affairs(Washington: Peter Force M. St. Clair Clarke, 1843), 4: 165.

[63]Descendants of Matthias Hatfield, 23, 48-50.

[64]Affidavit of Abigail Vergereau, August 30, 1783, Cornelius HATFIELD, McKinnon, 82.

[65]Ibid., Affidavit of George Ross, August 24, 1783.

[66]The Royal Gazette, February 9, 1780, ASNJ S2 V4: 178-179.

[67]W. Woodford Clayton, History of Union and Middlesex County, New Jersey(Philadelphia: Everts and Peck, 1882), 85-86.

[68]Certificate of Brig. Gen. Cortlandt Skinner, T 1/634.

[69]Hatfield, History of Elizabeth, 77-78, 482.

[70]Hartford Courant, March 6, 1781, https://www.newspapers.com/image/233716974.

[71]McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, 89.

[72]ASNJ S2 V3: 384; ASNJ S2 V3: 508.

[73]D.R Jack, History of the City and County of St. John(St. John, NB: J&A McMillan, 1883), 70-71.

[74]McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, 109; Joanna McKinnon, “Cornelius Hatfield, Jr., Loyalist, of Elizabeth Town and London, and Some of His Descendants,” The Genealogical Magazine of New Jerseyvol. 91 no. 3 (2016), 142, 144, 147-151.

[75]McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, 119.

[76]Lancaster Intelligencer, October 20, 1807, https://www.newspapers.com/image/556417383.

[77]The Vermont Journal, October 26, 1807, https://www.newspapers.com/image/489003666.

[78]Virginia Argus, October 30, 1807, https://www.newspapers.com/image/605064605.

[79]McKinnon, Cornelius HATFIELD, 122-123, 135.

[80]Will of Cornelius Hatfield, Jr., Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: Prob 11, Piece: 1674, TNA

7 Comments

This Cornelius Hatfield is a descendant of Thomas Hatfield (b. ca. 1610) who was born in England and fled to Holland. The descendants of Thomas came to America. The Colonel Matthias Ogden that Cornelius took prisoner was likely a relative of his. Cornelius Hatfield had a grandniece who married Robert Ogden. Another grandniece married Samuel Ogden. The lineage of this family (known as the Matthias Hatfield line) can be seen at https://www.theheritagelady.com/jerry…/hatftreb.htm

Elaine, thank you for the information. Are you a relative of Cornelius Hatfield? I was provided some valuable assistance in this article from the wife of a Cornelius Hatfield lineal relative who lives in New Zealand named Joanna McKinnon.

Congratulations on a riveting and obviously thoroughly researched piece – both narrowly focused as to topic but quite sweeping and expansive at the same time.

Rand, thank you very much! I am happy that I could help shed some more light on this fascinating Loyalist. Cornelius Hatfield could have been a major character in AMC’s Turn!

Enjoyed reading your interpretation Eric.

Thank you so much Jo,

I sincerely appreciate the assistance in researching this article. The results on the work you have done on Cornelius Hatfield are a treasure to History!

This is an interesting article on a Loyalist partisan. There are a number of interesting parallels between Hatfield and Loyalist James Moody. Even more than Moody, Hatfield seems to have relied on a network of close family members. Did Hatfield’s brothers and family form the nucleus of his partisan band?

Thanks for a nice look at one of the “Refugees” of the Revolution!