Leaving Colonel Francis Lord Rawdon to command in the field from Georgetown to Augusta, Lt. Gen. Charles Earl Cornwallis, the British General Officer Commanding in the South, marched from Winnsborough, South Carolina on January 8, 1781 at the start of his second campaign to conquer North Carolina.[1]

With him were 1,147 rank and file present and fit for duty, comprised of the Royal Artillery (40), the Royal Welch Fusiliers (286), the 33rd (328), the 2nd Battalion of the 71st (237), and the Royal North Carolina Regiment (256). If we allow for officers, NCOs, staff and drummers, the force under his immediate command totalled 1,350 men.

Detached to the west of Broad River was Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton with orders to press Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, who commanded a mixed body of revolutionary Continentals and militia. Under Tarleton were 977 rank and file present and fit for duty, comprised of the British Legion (451), the 1st Battalion of the 71st (249), the light company of the 71st (69), the Royal Fusiliers (167), and the 3rd company of the 16th, which was attached to the guns (41). When allowance is made for officers, NCOs, etc, his detachment came to 1,150 men.

By the 18th, the day on which he was joined by Major Gen. Alexander Leslie, Cornwallis had advanced to Turkey Creek. There and then he also received the distressing news that on the previous day Tarleton had come up with Morgan at the Cowpens and been comprehensively defeated in the ensuing battle. All his men were killed or captured apart from 223 officers and men of the British Legion cavalry who fled. The day was lost due partly to the impetuosity of Tarleton but pre-eminently to the superlative generalship of Morgan, who, despite fewer numbers, inferior troops and unpromising terrain, disposed and led his men in a masterly way.

“The late affair,” Cornwallis confessed to Rawdon, “has almost broke my heart.”

So what remained of Cornwallis’s depleted force? Well, Leslie had brought from New York a reinforcement of 1,140 rank and file present and fit for duty, composed of the Brigade of Guards (690), the Regiment of Bose (347), and a detachment of Hessian Jägers (103). Riding into camp were also the remains of the British Legion cavalry (174). Together, when we allow for officers, NCOs, etc., the total for all ranks came to 1,565. When this figure is added to the figure of 1,350, being the number of troops brought by Cornwallis himself from Winnsborough, his total depleted force comprised 2,915 men.[2]

Crippled though he was by Cowpens and the loss of his light troops there, Cornwallis resolved to press ahead with the winter campaign. Unfortunately for the Crown, it was a gamble that would not pay off.

In reaching his decision Cornwallis was influenced by a combination of three factors. Militarily, he hoped to overtake Morgan and release the Cowpens prisoners, but if he could not prevent Morgan from forming a junction with Major Gen. Nathanael Greene, the revolutionary commander-in-chief, he hoped to intercept the combined force between the barriers of the Yadkin and the Dan, compelling a general action which, given the disparity in seasoned troops, he was confident he would win.

Politically, he was conscious of the continuing imperative to make progress swiftly. In Britain there was a growing war weariness pervading all sections of society, compounded by the ruin of foreign and colonial trade, the knock-on effect on the rest of the economy, the weight of much increased taxation and public indebtedness, the collapse of private prosperity, and a rapid decline in the public finances. All in all, for a country of only eight million people, the costs of the war, both financial and otherwise, were becoming unsustainable.

Personally, he was aware how badly it would reflect on him if he made no attempt to release the Cowpens prisoners and abandoned the invasion of North Carolina a second time. Not only would his reputation be damaged but the effect on public opinion would undermine further the tenuous British hold on South Carolina and Georgia. As Rawdon had asserted on a similar occasion, “as much is to be done by opinion as by arms.”

It is now necessary, if my conclusions at the end of this article are to be placed in context, to summarise the rest of the campaign, together with the motives of the opposing commanders as events unfolded.

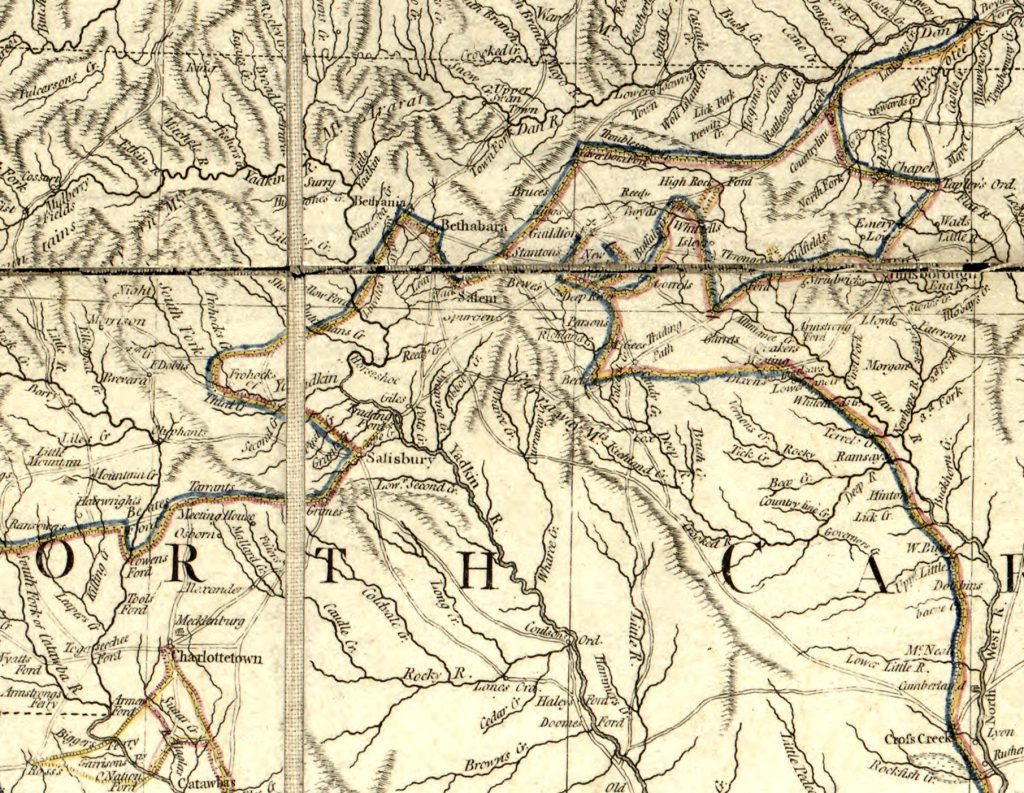

To begin with, Cornwallis’s pursuit of Morgan did not get off to a propitious start. He remained for two days after Cowpens at Turkey Creek. In the meantime Morgan rapidly retreated, sending his prisoners across the Catawba at Island Ford under an escort of militia and Lt. Col. William Washington’s dragoons, while with the rest of his force he passed Ramsour’s Mill to a lower ford, Sherrald’s, where he crossed on January 23. There he was almost immediately joined by the prisoners, whom he soon sent on over the Yadkin to Virginia.

If Cornwallis had marched promptly to the northward, he might have intercepted Morgan at Ramsour’s, but it was not to be. Apart from his delay in moving off, he mistakenly marched to the north-westward, eventually reaching Ramsour’s by the 25th. There he remained for three days, during which he came to a momentous decision which, no matter the immediate improvement in his mobility, might well inhibit his remaining in the back parts of North Carolina unless his supplies were in due course replenished from Wilmington. Charles Stedman, a British commissary who was there, recounted the event: “Lord Cornwallis, considering that the loss of his light troops could only be remedied by the activity of the whole army, resolved to destroy all the superfluous baggage. By first reducing the size and quantity of his own, he set an example which was cheerfully followed by all the officers under his command, although by so doing they sustained a considerable loss. No waggons were reserved except those loaded with hospital stores, salt, and ammunition, and four empty ones for the accommodation of the sick or wounded. The remainder of the waggons, baggage, and all the store of flour and rum were destroyed . . . And such was the ardour both of officers and soldiers, and their willingness to submit to any hardship for the promotion of the service, that this arrangement, which deprived them of all future prospect of spirituous liquors and even hazarded a regular supply of provisions, was acquiesced in without a murmur.” In the evening of the 29th Cornwallis arrived at the banks of the Catawba, but a heavy rain fell in the night and swelled the river so much that it was impassable for the next two days.

Meanwhile, on learning of Cowpens, Greene had set his troops in motion from Hick’s Creek towards Salisbury, while he himself galloped across country to take personal command of Morgan’s force. He reached Morgan at Sherrald’s Ford on the 30th. When the Catawba began to drop the following day, he decided to hurry on with Morgan and his men to the Trading Ford on the Yadkin, leaving Brig. Gen. William Lee Davidson with some militia to dispute Cornwallis’s passage of the Catawba. At dawn on February 1 Cornwallis crossed the river under a galling fire at Cowan’s Ford and joined up with Lt. Col. James Webster,[3] who had passed higher up at Beattie’s. Davidson was killed. Brig. Gen. Charles O’Hara[4] with the van pressed ahead to the Trading Ford, which he reached on the 3rd just as the last of the enemy crossed on boats which Greene with admirable foresight had collected. With no boats available on the western bank, and with the swollen river unfordable, Cornwallis halted for two days at Salisbury to collect provisions, after which he turned north to the Shallow Ford ten miles up river, where, having been delayed by the height of creeks on a necessarily circuitous route, he crossed in the evening of the 7th. On the same day Greene’s men from Hick’s Creek arrived at Guilford. Joining up with them, Greene convened a council of war there on the 9th, which, taking into account that his combined force amounted to only 1,426 Continental infantry and 600 poorly armed and constantly fluctuating militia, decided not to risk a general action but to retreat immediately over the Dan. Detaching a light corps under Col. Otho Holland Williams[5] to mislead Cornwallis that he was headed for the upper fords of the river, he pressed ahead with his main body to Irwin’s Ferry on the lower reach. There he crossed on the 14th, followed by Williams’ corps during the night, having again assembled, with admirable foresight, all the available boats. In hot pursuit the British van arrived a few hours later.

We have already related the destruction of Cornwallis’s baggage, stores and wagons at Ramsour’s Mill. Another more serious consequence of Cowpens now ensued. If Cornwallis had not lost his light troops there, his total force would now have come to some 3,400 men (including artillery) when allowance is made for casualties incurred at Cowpens and during his advance. Now that Greene had been driven into Virginia, it would have made sound strategic sense to keep him where he was while Cornwallis was left to assemble in relative security the numerous loyalists in North Carolina and re-establish British authority there. To this end a compelling course would have been for him to divide his force so that half remained on the Dan while the rest withdrew into the interior and set about reinstating government under the Crown. With so large a British force remaining on the Dan, Greene would have run the grave risk of being caught in the process of repassage if he had attempted it. Diversions might have been made and he may have succeeded, but even so, he would have faced entrapment between Cornwallis’s two divisions and either a general action in which Cornwallis had a marked superiority in seasoned troops or, if at all possible, another ignominious flight across the Dan. Neither of Cornwallis’s divisions would have been easily defeated in detail.

Yet dividing Cornwallis’s force was no longer an option. Reduced as he was to 2,800 men (including artillery), he saw no alternative, after halting for a while, but to proceed by easy marches to Hillsborough, where he arrived on the 20th. Erecting the King’s standard, he invited by proclamation all loyal subjects to come forward and take an active part in restoring order and constitutional government.

With no force opposing a repassage of the Dan, Greene rightly concluded that it was essential to disrupt Cornwallis’s operations, prevent the loyalists from assembling, and impress the revolutionaries with his presence. On the 19th Lt. Col. “Light Horse Harry” Lee and his Legion were dispatched across the river with orders to intimidate the loyalists, to rouse the drooping spirits of the revolutionaries, “to alarm the enemy by night, and to harass them by day.” Four days later he joined up with Brig. Gen. Andrew Pickens and his militia, who had remained in North Carolina. On the 20th Lee was followed across by Williams with a light corps, who was ordered to observe the motions of the British and embrace the first opportunity of giving them an advantageous blow. Reinforced by Brig. Gen. Edward Stevens and several hundred Virginia militia, Greene passed with the main body on the 22nd, intent—when reinforced further—on “ruining” Cornwallis.

Meanwhile Cornwallis was greatly disappointed in his expectations of being joined by the loyalists, almost all of whom, as Tarleton explained, were prepared to assemble only in perfect security: “Soon after the King’s standard was erected at Hillsborough, many hundred inhabitants of the surrounding districts rode into the British camp to talk over the proclamation, inquire the news of the day, and take a view of the King’s troops. The generality of these visitants seemed desirous of peace but averse to every exertion that might tend to procure it. They acknowledged the Continentals were chased out of the province, but they declared they soon expected them to return and the dread of violence and persecution[6] prevented their taking a decided part in a cause which yet appeared dangerous.” An exception was Dr. John Pyle, who assembled some 2 or 300 loyalists between the Haw and Deep Rivers and began marching for Hillsborough. Mistaking Lee and Pickens’ men for Tarleton’s, they were inhumanly butchered on the 25th. “This affair,” concluded Pickens, “has been of infinite service. It has knocked up Toryism altogether in this part.” A final nail was soon after placed in the coffin of Cornwallis’s expectations when another body of assembled loyalists was mistakenly attacked on March 4 by Tarleton’s men, who killed four and badly cut up twenty or thirty. “In the case of Pyle’s men,” commented Major Joseph Graham, who was there, “they were cut up by the Americans and thought it was the British; in this case they were cut up by the British and thought it was the Americans. These miscarriages so completely broke the spirit of the loyalists in those parts that no party was known afterwards to attempt to join the British in these or the adjoining counties.”

The attitude of the loyalists encountered by Cornwallis at Hillsborough is perhaps best described in the following anecdote related by his commissary, Stedman:

The commissary, who considered it as his duty not only to furnish provisions to the army but also to learn the disposition of the inhabitants, fell in about this time with a very sensible man, a Quaker, who, being interrogated as to the state of the country, replied that it was the general wish of the people to be reunited to Britain; but that they had been so often deceived in promises of support, and the British had so frequently relinquished posts, that the people were now afraid to join the British army lest they should leave the province, in which case the resentment of the revolutioners would be exercised with more cruelty; that although the men might escape or go with the army, yet such was the diabolical conduct of those people that they would inflict the severest punishment upon their families. ‘Perhaps,’ said the Quaker, ‘thou art not acquainted with the conduct of thy enemies towards those who wish well to the cause thou art engaged in. There are some who have lived two and even three years in the woods without daring to go to their houses but have been secretly supported by their families. Others, having walked out of their houses under a promise of being safe, have proceeded but a few yards before they have been shot. Others have been tied to a tree and severely whipped. I will tell thee of one instance of cruelty: a party surrounded the house of a loyalist; a few entered; the man and his wife were in bed; the husband was shot dead by the side of his wife.’ The writer of this replied that those circumstances were horrid but under what government could they be so happy as when enjoying the privileges of Englishmen? ‘True,’ said the Quaker, ‘but the people have experienced such distress that I believe they would submit to any government in the world to obtain peace.’ The commissary, finding the gentleman to be a very sensible, intelligent man, took great pains to find out his character. Upon enquiry he proved to be a man of the most irreproachable manners and well known to some gentlemen of North Carolina then in our army, and whose veracity was undoubted.

It was on February 25 that Cornwallis received certain intelligence that Greene, having been reinforced, had recrossed the Dan. Judging it no longer expedient to separate his force, he recalled a detachment commanded by Tarleton. Destitute of forage and provisions, and too distant—after Greene’s return—to protect the great body of loyalists residing between the Haw and Deep Rivers, he next day quit Hillsborough, passed the Haw, and encamped near Alamance Creek. With Lee and Williams hovering around him, and with Greene constantly moving nearby between High Rock Ford, Boyd’s Mill and Speedwell’s Iron Works, he had no option but to remain compact, controlling no ground beyond his pickets. “From that time,” wrote O’Hara to the Duke of Grafton, “the two armys were never above twenty miles asunder, they constantly avoiding a general action and we as industriously seeking it. These operations obliged the two armys to make numberless moves, which it is impossible to detail.” On his tactics during this period Greene commented as follows: “I have been obliged to practice that by finesse which I dare not attempt by force. I know the people have been in anxious suspence waiting the event of an action, but let the consequence of censure be what it may, nothing shall hurry me into a measure that is not suggested by prudence or connects with it the interest of the department in which I have the honor to command.”

Eventually, on March 11, Greene formed a junction with a Virginia regiment of 18 months’ men and a considerable body of North Carolina and Virginia militia. Thus reinforced, and despite sending Pickens back to South Carolina with a very small number of South Carolinians and Georgians, he now offered battle. It took place on the 15th at Guilford. From a British perspective Cornwallis provides a brief account of the affair in his letter of March 17 to Lord George Germain, the British Secretary of State.[7] It is unnecessary to elaborate here, save to state the motives of the commanders, the disposition of the enemy, a few supplementary facts, and the sequel.

According to Cornwallis, “I was determined to fight the rebel army if it approached me, being convinced that it would be impossible to succeed in that great object of our arduous campaign, the calling forth the numerous loyalists of North Carolina, whilst a doubt remained on their minds of the superiority of our arms.” In effect he was looking for as decisive a victory as at Camden, one that would demolish the revolutionary forces and compel the remnants to retreat over the Dan or, in the case of the militia, to flee to their homes. Such an outcome might well convince the timid loyalists at last to assemble, without whose assistance the reinstatement of constitutional government was a forlorn hope.

Greene explained his motives in a letter of the 18th to George Washington: “Our force, as you will see by the returns, were respectable, and the probability of not being able to keep it long in the field, and the difficulty of subsisting men in this exhausted country, together with the great advantages which would result from the action if we were victorious and the little injury if we were otherwise, determin’d me to bring on an action as soon as possible.” At worst he hoped to leave Cornwallis with no decisive victory and a large number of wounded. In that event, if Cornwallis had to retire, the most serious cases would need to be left behind and fall into the revolutionaries’ hands, whilst the rest, who remained with Cornwallis, would encumber his further operations. Such was indeed the outcome.

The battleground chosen by Greene was approachable from the west along a road through a narrow defile shouldered by rising ground on both sides and lined with dense copses that continued unbroken to within half a mile of Guilford Courthouse. At this point the ground had been cleared on both sides of the road, leaving an open space, broken only by fences, about 500 yards square. Ahead of this first clearing the woods again closed upon the road for another half mile, at the end of which there came another open space of cultivated ground, seamed by hollows, around the courthouse itself. Greene’s first line, composed principally of North Carolina militia, was formed behind a rail fence along the edge of the first clearing. Ordered by Greene to fire only two rounds before retiring, they did so, appreciably thinning the British ranks.

About 300 yards behind the first line was Greene’s second, composed of Virginia militia. “Posted in the woods and covering themselves with trees, they kept up for a considerable time a galling fire, which did great execution.” At last the right gave way, paving the way for the much depleted British left wing to attack the Continentals, who formed Greene’s third and principal line. It was drawn up in a curve along the brow of the courthouse hill a few hundred yards behind the second line and somewhat out of alignment with it. A most bloody contest ensued, which might have gone either way, but true to his resolution not to risk the destruction of his entire army, Greene eventually decided to withdraw, although the remnants of his first line were still active on his left. He did so “with order and regularity.” There was little pursuit, for Cornwallis’s troops were spent with hard fighting and their long march to the battlefield.

Until recently there had been much uncertainty about the number of troops brought by Cornwallis to the battle, uncertainty which an essay of mine has done much to dispel. In it I provide compelling reasons for concluding that his total force came to 2,385 men.[8] Greene’s numbers remain imprecise, but they are generally reckoned to have amounted to some 4,500, of whom about 1,750 were Continentals and the rest militia.

Cornwallis’s casualties in the battle came to 93 killed, 413 wounded, and 26 missing—a total of 532.[9] Of his Continentals, Greene admitted to losing 57 killed, 113 wounded, and 161 missing—a total of 331. No reliable figures for his militia have ever been published.

“Never perhaps has the prowess of the British soldier been seen to greater advantage than in this obstinate and bloody combat,” concluded Fortescue. “Starting half-starved on a march of twelve miles, the troops attacked an enemy, fresh and strong, which not only outnumbered them by more than two to one, but which was so posted, by Greene’s excellent judgment, as to afford every possible advantage to its natural superiority in bushcraft, armament, and marksmanship. Yet, though heavily punished, they forced the Americans from the shelter of the forest and drove them from the field.” Nevertheless, “the victory, though a brilliant feat of arms, was no victory. Greene did indeed retreat, and the most part of his militia deserted to their homes so that his losses were never actually ascertained, but Cornwallis had gained no solid advantage to compensate for the sacrifice of life and he was now too weak farther to prosecute” his campaign. All in all, the victory was, as Major Gen. William Phillips[10] truly stated, the sort that ruins an army. If only Cornwallis had not lost his light troops at Cowpens, the story might well have been different.

Cornwallis’s troops had cheerfully undergone hardships, fatigue and starvation, but they were now terribly reduced in numbers and almost destitute of provisions and other supplies. He had no choice but to accept the inevitable and on the third day after the battle he began to make his way towards Cross Creek, where, in expectation of being supplied by water carriage from Wilmington, he intended to halt as a proper place not only to refresh and refit the troops but also to dispose of his numerous wounded, sixty-four of whom he was obliged to leave behind at New Garden Meeting House.

Having lost a quarter of his men at Guilford, and encumbered with wounded, Cornwallis was in no position to face another engagement, for, if his losses were equally severe, they might involve the demolition of his entire army. Recognising this fact, Greene began to pursue him as far as Ramsey’s Mill on Deep River, intent on giving battle. There, on the 28th, he found that the British had partly destroyed a temporary bridge which they had built across the river and had retired southward a few hours earlier. The country below was so barren, his provisions were so short, and the term of much of his Virginia militia was so soon to expire, that Greene could not pursue farther.

Cornwallis entered Cross Creek at the beginning of April. To his dismay he could not open a water communication with Wilmington. The distance, the narrowness of the Cape Fear River, the commanding elevation of the banks, and the hostile sentiments of a great part of the adjoining inhabitants made the navigation impracticable. The Highlanders in and around Cross Creek remained loyal, but they declined to embody for the same reasons as the rest of the loyalists. Under these circumstances Cornwallis decided to march his whole force to Wilmington.

Cornwallis arrived in the vicinity of Wilmington on the 7th. Writing shortly after to the Duke of Grafton, O’Hara remarked, “We feel at this moment the sad and fatal effects of our loss [at the Battle of Guilford]. Nearly one half of our best officers and soldiers were either killed or wounded and what remains are so completely worn out . . . [that], entre nous, the spirit of our little army has evaporated a good deal.”

In the meantime Greene had come to a decision of key strategic importance. Writing to George Washington on March 29, he remarked, “If the enemy falls down towards Wilmington, they will be in a position where it would be impossible for us to injure them if we had a force. In this critical and distressing situation I am determined to carry the war immediately into South Carolina. The enemy will be obliged to follow us or give up their posts in that State. If the former takes place, it will draw the war out of this State and give it an opportunity to raise its proportion of men. If they leave their posts to fall, they must lose more there than they can gain here. If we continue in this State, the enemy will hold their possessions in both.” Though brilliant in its concept, the decision was risky, for, as stated in The Greene Papers, he was violating established military principles by leaving an enemy army virtually unchallenged in his rear. Yet he was well aware of the unorthodoxy of his design, as he explained to James Emmet, a North Carolina officer: “Don’t be surpris’d if my movements don’t correspond with your ideas of military propriety. War is an intricate business, and people are often sav’d by ways and means they least look for or expect.”

Sending Lee ahead to surprise British posts on the Santee and Congaree, Greene began his march from Ramsey’s Mill on the 6th. The die was cast.

It is easy to be wise after the event when we look back on the winter campaign, but the question is not so much why the campaign failed so dismally—to which this article provides the answers—as why it ever took place. The decision to invade North Carolina was taken in the summer of 1780 when both South Carolina and Georgia were in a quiescent state. As long as they remained so, it seemed reasonable to assume that public order could be maintained by leaving relatively few troops in support of the royal militia. Yet by the time that the campaign began, the situation militarily had become critical, with the country outside Charlestown and Savannah preponderantly under revolutionary control—and the royal militia a busted flush.[11] In the light of the changed circumstances it was folly, as in the autumn campaign, to throw caution to the winds and proceed with the invasion, for, whatever the outcome, much was to be lost if success or failure in North Carolina was vitiated or attended by losing even more control of what little remained of the territory held by the British to the south. Far better if Cornwallis had abandoned the campaign before it began and simply used the whole of Leslie’s recent reinforcement—2,000 men—to put South Carolina and Georgia into a better state of defense. In the fullness of time, if the measures proposed by me elsewhere had been followed, the invasion of North Carolina would have become feasible,[12]but for the present it remained a bridge too far.

So strategically it was wrong to begin the campaign, and even worse to continue with it after Cowpens, for, by destroying his extensive train of baggage and provisions, Cornwallis was perforce unable, unless resupplied, to remain in the back parts of North Carolina, a prerequisite if the loyalists were to embody. It almost beggars belief that, with the North Carolinians in Lt. Col. John Hamilton’s corps available to advise,[13] his intelligence was so poor as not to indicate that the only means of resupply, by water from Wilmington to Cross Creek, was impractical.

So what of Cornwallis’s motives for continuing the campaign after Cowpens? Militarily, his hopes of releasing the Cowpens prisoners were almost immediately dashed. He delayed for two days before moving off from Turkey Creek, spent three at Ramsour’s in destroying his wagons, baggage and provisions, and had to wait two at the swollen Catawba till it was passable. By then the prisoners, who had been swiftly sent on to Virginia, had a head start of over a week and could not be overtaken. As to the rest of the campaign, Cornwallis’s depleted force was sufficient to drive Greene out of North Carolina into Virginia, but insufficient to keep him there. Having lost his light troops at Cowpens, Cornwallis no longer had men enough to divide his force by leaving half to prevent Greene’s repassage of the Dan while he moved off with the rest to set about embodying the adherents to the Crown. The upshot was that, as soon as he marched from the river to Hillsborough, Greene returned, and this being so, the loyalists declined en masse to embody, being prepared to do so only in perfect security. Ipso facto, “that great object of our arduous campaign, the calling forth the numerous loyalists of North Carolina” was an abject failure—and so, therefore, was the entire campaign. In this respect the Battle of Guilford was to a degree a mere sideshow, for, if Greene, astute commander as he was, avoided the demolition of his army, which he did, Cornwallis’s impasse with the loyalists would remain. Unable to be resupplied, Cornwallis would in any event have had to withdraw from the back parts of the province—the outcome of the battle simply precipitated it.

As regards Cornwallis’s personal reasons for continuing the campaign, it is the mark of a great commander like Greene that he can sublimate them to the wider strategic concerns of the moment. This Cornwallis failed to do. Admittedly, abandoning the campaign would have adversely reflected on his reputation and on public opinion in South Carolina and Georgia, but not to the extent of threatening Britain’s tenuous hold on those provinces.

The third motive propelling Cornwallis to precipitate action was the political imperative of making progress swiftly. Unfortunately for him he struck the wrong balance between political and military considerations, acted prematurely, and the rest is history.

[1]For an account of the first campaign and its abandonment, see Ian Saberton, “Cornwallis and the autumn campaign of 1780 ― His advance from Camden to Charlotte,” in his The American Revolutionary War in the South: A Re-evaluation from a British Perspective in the Light of The Cornwallis Papers (Grosvenor House Publishing Ltd, 2018), 56-64, together with his “Cornwallis quits Charlotte, abandoning the autumn campaign of 1780,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 19, 2019.

[2]In this and the preceding paragraphs the figures for rank and file present and fit for duty are as stated in Ian Saberton ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War (“CP”), 6 vols (Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010), IV, 61. Here and later the totals for all ranks are extrapolated from the totals for rank and file by using a factor of 17.5 percent, being an accurate and consistent representation of the officers, NCOs, etc, in British and British American regiments. The exceptions are the figures for all ranks in the remnant of the British Legion and in the detachment of Royal Artillery, which are as stated in CP, IV, 63.

[3]Commanding the 33rd Regiment, of which Cornwallis was Colonel.

[4]Commanding the Brigade of Guards.

[5]Greene’s Adjutant General and commander of the 6th Maryland Continental Regiment.

[6]See Ian Saberton, “Midsummer 1780 in the Carolinas and Georgia—Events predating the Battle of Camden,” Journal of the American Revolution, July 15, 2019.

[8]See Ian Saberton, “How many troops did Cornwallis actually bring to the Battle of Guilford?” in his The American Revolutionary War in the South, 65-7.

[10]Commanding a British expeditionary force in Virginia.

[11]See Ian Saberton, “Cornwallis’s Refitment at Winnsborough and the Start of the Winter Campaign, November-January, 1780-81,” Journal of the American Revolution, March 18, 2019.

[12]See Ian Saberton, “Was the American Revolutionary War in the south winnable by the British?” in his The American Revolutionary War in the South, 1-21.

[13]For a biographical note on Hamilton, together with a description of his corps, see CP, I, 55.

Bibliography

John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Court House: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (John Wiley & Sons, 1997)

Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, volume III (Macmillan and Co. Ltd., 1902)

James Graham, The Life of Daniel Morgan (New York, 1856)

Joseph Graham, “Narrative,” in William Henry Hoyt ed.,The Papers of Archibald D. Murphey (Publications of the North Carolina Historical Commission, Raleigh, 1914)

The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, volumes VII and VIII, edited by Dennis M. Conrad, Roger N. Parks, Richard K. Showman, et al. (The University of North Carolina Press, 1994-5)

Ian Saberton ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, 6 vols (The Naval & Military Press Ltd., 2010)

David Schenck, North Carolina 1780-81 (Raleigh, 1889)

The South Carolina Historical Magazine, LXV (1964)

Charles Stedman, History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War (London, 1792)

Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (London, 1787)

Theodore Thayer, Nathanael Greene: Strategist of the American Revolution (Twayne Publishers, New York, 1960)

The Rt. Hon. Sir George Otto Trevelyan Bt., The History of the American Revolution, volume VI (Longmans, Green, and Co., 1915)

Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution (The Macmillan Co., New York, 1952)

Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: The American Adventure (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1970)

2 Comments

Good article, but Cornwallis was obsessed with North Carolina. Remember that his orders from Clinton were to protect and secure South Carolina and he was not to move to North Carolina until he could ensure the safety of South Carolina. Cornwallis also had help in the form of Lord Germain who believed that thousands of Loyalists would rise and provide the means to keep control of South Carolina. After the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Cornwallis moved to Hilsborough in hopes of getting food, medicine and help from the loyalists. These failed to materialize and he was then forced to go to Wilmington. The only part of North and South Carolina he controlled was the part he was occupying at the time. As soon as he left the area control reverted to the Rebels.

Noted, Robert. Thank you.