The Revolutionary War in the Carolinas after the fall of Charleston was a great arena of war with hundreds of small battlefields. Some were battles involving a few dozen men, Tory or Whig Americans fighting each other or Whigs fighting British regulars. Other engagements involved hundreds of men, with dozens of casualties. Today, most of the names are unknown or even meaningless except to local citizens or historians. Often these battles did have significance, sometimes out of proportion to the numbers that fought or died there. One such encounter took place on the Mt. Joseph plantation about ninety-five miles from Charleston.

After the fall of Charleston on May 12, 1780, British general Charles Lord Cornwallis went about a conquest of South Carolina. Defeating American forces at the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780, Cornwallis established posts to protect British gains at various small outposts between Camden and Charleston. These posts served both as protection for supply lines and as symbols of British presence to encourage Loyalists to rally to the King’s colors.

One of the posts was at St. Joseph plantation, a farm owned by Rebecca Motte. Originally owned by her brother Miles Brewton, she inherited the property upon his death in August 1775. Elected to the Second Continental Congress, Brewton was lost at sea with his wife and children en route to Philadelphia. Motte, whose husband died in 1780, was a well-known Whig sympathizer with a son-in-law, Whig Thomas Pinckney, recovering from wounds with her daughter in Charleston.[1] She was at her plantation home with three other women in late January 1781 when the British came.

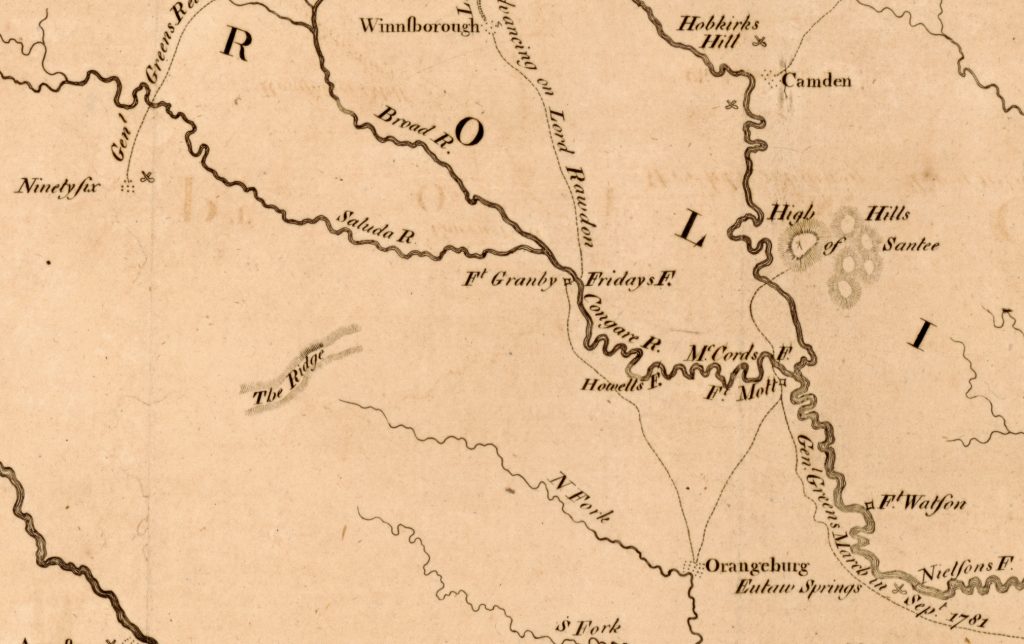

Located on a loop of the Congaree River, the plantation house was situated on a small knoll called Buckhead Hill. Continental Army lieutenant colonel Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee described the importance of the location: “This post was the principal depot of the convoys from Charleston to Camden, and sometimes of those destined for Fort Granby and Ninety-Six.”[2] From Camden to Charleston the British built other small fortifications to protect their supply lines. Fort Watson on the Santee, Nelson’s Ferry and Fort Granby on the Congaree, and Orangeburg gave the British a line of outposts to protect their communications between Camden and the critical base at Charleston on the coast.

Commanding the troops at Fort Motte was Capt.-Lt. Donald McPherson. There were eighty men of the British 84th Regiment, fifty-nine Hessians, and about forty-five Loyalist militiamen. An unknown number of dragoons rounded out the garrison.

After his pyrrhic victory at Guilford Court House on March 15, 1781, Lord Cornwallis retreated to Wilmington, North Carolina, never again to enter South Carolina; his destiny would ultimately take him to Virginia. Lord Rawdon became commander of the main body of British troops remaining in South Carolina, taking station at Camden.

With Cornwallis out of the way, American general Nathanael Greene went on the offensive. He kept a small force of Continental troops intact and sent out detachments to wrest control of the countryside from the British. He astutely ordered Henry Lee to take his legion and join forces with Francis Marion and his militia. The two detachments united on April 14. Putting the two together ended up as a happy combination that would soon experience success.

The combined forces wasted no time in attacking Fort Watson at Scott’s Lake. Without any artillery, Marion and Lee acted upon an idea from one of their subordinates to come up with a creative way of capturing the fort. Unable to knock down the walls, they built a tower that allowed them to shoot down into the enemy position. The British garrison, a mixed group of regulars and Loyalist militia, surrendered on April 23.

The Continental Army and its militia under Nathanael Greene were defeated at Hobirk’s Hill on April 25 but Greene was able to escape from Lord Rawdon. When Rawdon failed to follow up his victory, Greene encouraged Marion and Lee by sending a six-pound cannon under Capt. Ebenezer Finley.

Marion and Lee proceeded to the curve in the Congaeree River, arriving at Fort Motte on May 6. Lee had about three hundred men, mostly veteran Continental soldiers from his Legion, the North Carolina Line, and some Marylanders. Marion’s forces consisted of approximately 150 militiamen.

On May 8, the American forces took up positions around the British. Lee took post upon the height where Mrs. Motte had taken residence after being expelled from her home. “brigadier Marion occupied the eastern declivity of the ridge on which the fort stood.”[4] Finley and his six-pounder took up position on a small hillock with Marion’s men to the east of the fortifications. American troops surrounded the British fortifications and fired rifles and muskets to keep the British occupied as the Americans began a sap, a trench which would allow them to approach the outer line of defenses under cover.

It was decided that once the sap was close to the abatis, the Continentals would rush the fort, covered by the fire of the cannon and militia. Using soldiers and slaves, the sap daily moved closer and closer. Gunfire had little effect on the garrison and the earthen wall kept the cannon from doing any real damage to the palisade. Nevertheless, the muskets and cannon kept the British under cover.

On May 10 rumors that Lord Rawdon was on his way from Camden reached Marion and Lee. If they could not force the British out, Rawdon might arrive in time to lift the siege. No one knows who came up with the idea but Lee described the thoughts of the Americans upon learning of the approach of Rawdon and the need to hurry their work: “The large mansion in the centre of the encircling trench, left but a few yards of the ground within the enemy’s works uncovered; burning the house must force their surrender.”[5] It was decided to fire arrows with combustible materials into the structure. The troops immediately began to fashion bows and arrows for that purpose.

Living in the farmhouse with Mrs. Motte and her family and enjoying her hospitality throughout the siege had formed a bond between the officers and her. Lee reluctantly advised her of the plans to destroy the mansion house in order to force the British out of their position. The response was unexpected. “With the smile of complacency this exemplary lady listened to the embarrassed officer, and gave instant relief to his agitated feelings, by declaring, that she was gratified with the opportunity of contributing to the good of her country, and that she should view the approaching scene with delight. Shortly after, seeing accidently the bow and arrows which had been prepared, she sent for the lieutenant colonel, and presenting him with a bow and its apparatus imported from India, she requested the substitution of these, as probably better adapted for the object than those we had provided.”[6]

On May 12, troops were moved into position for the final assault but first Marion sent Doctor Matthew Irvine of Lee’s Legion with a flag of truce to induce the British to give up. Although McPherson cordially received the offer, he refused to surrender. The doctor returned to the American lines at about noon as the day began to heat up and everything dried up. Marion ordered the arrows to fly: “The first arrow struck, and communicated its fire; a second was shot at another quarter of the roof, and a third at a third quarter, this last also took effect; and like the first, soon kindled a blaze.”[7] McPherson sent men onto the roof to squelch the budding flames but Finley opened fire with his cannon, driving off the working parties trying to pull off the flaming shingles. Unable to douse the fire, McPherson put up a white flag at 1:00 pm that afternoon.

A different account of the setting of fire to the Mansion is contained in a book written by one of the militia officers, William Dobein James: “This deed of Mrs. Motte has been deservedly celebrated. Her intention to sacrifice her valuable property was patriotic; but the house was not burnt, as is stated by historians, nor was it fired by an arrow from an African bow, as sung by the poet. Nathan Savage, a private in Marion’s brigade, made up a ball of rosin and brimstone, to which he set fire, slung it on the roof of the house.”[8] Did he use an actual sling to propel the burning object to the roof? The distance from the trench to the wall and on to the top of the two-story house makes it unlikely that he threw the flaming ball all the way onto the roof. Nevertheless, the writer was a member of Marion’s militia and he does cite the name of the man who performed the amazing feat, so it is possible. Most accounts mention the arrows, at least one describing the arrows being fired by muskets.[9]

Both sides helped stanch the flames and the mansion was saved. The officers of each side were treated to a meal at the farmhouse. Evidently the lady of the plantation held no grudge: “The deportment and demeanor of Mrs. Motte gave a zest to the pleasures of the table. She did its honors with that unaffected politeness, which ever excites esteem mingled with admiration. Conversing with ease, vivacity and good sense, she obliterated our recollection of the injury she had received; and though warmly attached to the defenders of her country, the engaging amiability of her manners, left it doubtful which set of officers constituted these defenders.”[10] The British soldiers were paroled by Lee and sent to join Rawdon. Marion took charge of the Loyalists, of which three were hanged for various offenses.

Rawdon eventually retreated back to Charleston. Fort Granby, Orangeburg, and Nelson’s Ferry fell to marauding Americans. Many small actions were fought after the fall of Fort Motte, and the network of British outposts was shattered during the spring and summer of 1781. Rawdon sortied from Charleston to prevent the loss of the last outpost at Ninety-Six in June but was forced to give up the post as it was unsustainable. Without a regular British presence in the countryside, the Loyalists would not, or could not, rally to the King’s colors. Rawdon’s replacement, Col. Alexander Stewart, made one last attempt to rid the state of Continental forces at the battle of Eutaw Springs on September 8, 1781 but the tactical victory could not prevent the strategic defeat. Small actions such as that at Fort Motte spelled the doom of the Crown’s influence in South Carolina.

Today a small monument stands on the site of the house that formed the center of the British position. Recent archaeology has proven that the marker, placed in 1909 by the local Daughters of the American Revolution, was placed accurately at the sight of the Mansion.[11]

[1]Steven D. Smith, et. al., “Obstinate and Strong:” The History and Archaeology of the Siege of Fort Motte,” University of South Carolina: South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2007, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c5a0/4b6560dbf750c7896535253418b2e2e9350b.pdf, 13.

[2]Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States, Volume II (New York, Bradsord and Inskeep, 1812), 73.

[3]Smith, “Obstinate and Strong,” 21-22.

[8]William Dobein James, A Sketch of the Life of Brig. Gen. Francis Marion and A History of his Brigade, from its Rise in June, 1780, until Disbanded in December, 1782; With Descriptions of Characters and Scenes, not heretofore published. Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/923/923.txt,2008, accessed February 17, 2020.

Recent Articles

Dr. Warren’s Crucial Informant

John Dickinson and His Letters

North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution

Recent Comments

My family is descended from Luther Kinnicutt. We have discovered information about...

We all have a bias toward believing that our own contribution to...

Thank you! I grew up in Middlesex County during the Bicentennial, so...