Author’s note: Continental Navy midshipman Nathaniel Fanning’s eyewitness account of the American Revolution’s most famous naval battle is among the most detailed available. This article presents his account, rewritten in the third person with some modifications for clarity.

A six-knot breeze blew from the south southwest off Flamborough Head as the Continental Navy ship Bonhomme Richard under the command of Commodore John Paul Jones closed in on a potential target on a late September afternoon in 1779.[1] This unidentified vessel drew up her courses and displayed St. George’s colors.[2] Richard adjusted her sails and displayed her recently adopted striped American flag. Two other Continental Navy vessels, Pallas and Alliance, that accompanied Richard chased after a large ship that attempted to escape to the leeward, against Jones’s orders. The fourth vessel of the small American squadron, Vengeance, was well to Richard’s stern leaving Jones alone to contend with a warship that appeared to be superior in arms.

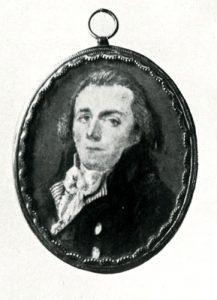

Nathaniel Fanning, a twenty-four-year-old midshipman from Connecticut, was assigned as the captain of the main top. In preparation for the anticipated battle, Fanning along with the captains of the fore and mizzen tops was ordered to report to the quarterdeck. The other two were also midshipmen, but not quite seventeen. All three junior officers received orders directly from Jones. They were to aim their fire at the enemy’s tops using muskets, blunderbusses, swivels, and cohorns (small mortars). A favorite British tactic was firing down on their enemy’s quarterdeck to kill or disrupt those of the opposing ship. Therefore, silencing the opponent’s top-platforms was crucial. With their orders understood, the topmen took a cask of water for hydration plus a double ration of grog (perhaps for “liquid courage”) and climbed aloft to their stations. By the time the three groups of topmen were ready to commence firing their weapons, the opponent hauled down its generic British St. George ensign and hoisted a red navy flag with the union jack in its canton. The British ship’s captain then carefully nailed it to the flagstaff.[3] The unknown antagonist turned out to be His Britannic Majesty’s forty-four-gun warship Serapis under the command of Capt. Richard Pearson.[4]

Richard was missing several officers and crewmen who had been ordered to sail captured prize ships to France as well as deserters who left after a recent ill-fated land escapade at Leith, Scotland. In addition, a lieutenant and a crew of twenty men manning a tender were left many miles behind when Jones had spied the British warship and sailed off to engage the enemy.[5] The cannon available to Richard for the battle were as follows: six 18-pounders, fourteen 12-pounders, fourteen 9-pounders, and four 6-pounders.

There were a number of captives onboard, men who had been apprehended while taking their vessels as prizes. Seven or eight of these prisoners chose to fight with the Americans, but most declined. Accounting for all the additions and subtractions, the Richard’s fighting crew approximated three hundred eighty men and boys. About three hundred were Americans, the rest English, French, Scottish, Irish, Portuguese, and Maltese sailors. In the maintop were fifteen marines, four sailors, and Fanning. In the foretop were one midshipman, ten marines and three sailors; in the mizzen-top one midshipman, six marines, and two sailors. A French Army colonel with twenty French marines manned the poop.[6]

The Serapis carried a company of 305 officers and men among whom were 15 Lascars (East-Indians) assigned to duty in different parts of the ship. The warship was officially rated as a forty-four, but she mounted fifty guns: twenty 18-pounders, twenty 9-pounders, and ten 6-pounders at the beginning of this specific battle.

On the night of September 22, 1779, Bonhomme Richard and the British ship of war Serapis engaged in an epic battle off Flamborough Head on the Yorkshire coast by the North Sea, just south of Scarborough. The two vessels first nearly came within hailing distance of each other when Captain Jones ordered the yards of Richard slung with chains and her courses hauled to. Serapis tacked in response and bore down to attack the American vessel. Just after eight in the evening, the moon rose and shone through parted clouds. An unusually calm sea surface lent an eerie sheen to the scene. Before any shots were fired, an officer on Serapis hailed the American ship and arrogantly inquired “What ship is this?” Richard’s quick response was, “Come a little nearer, and I will tell you.”[7]

The next question was, “What are you laden with?” Jones answered through his speaking trumpet, “Round, grape, and double headed-shot.”[8]

Serapis then discharged it supper and quarterdeck guns into Richard, but not those from the lower deck guns, perhaps thinking that it could overpower the Americans with fewer weapons. Richard returned the fire and the lengthy historic battle began.

As a result of the British opening broadside, the three starboard forward deck guns of Richard were hit and many men stationed by them were killed or wounded. Jones, aware of the carnage, gave orders to hold fire on three 18-pounders on that deck as well as the gun crews assigned to discharge their guns on the lower decks. Richard appeared overmatched and vulnerable so Pearson maneuvered his ship to a position under the Yankee’s stern. Jones was now in a disadvantage that he could not prevent. The British commenced to rake Richard with broadsides and musket showers from the tops aloft. Several of Serapis’18-pound shots passed completely through the sails and masts of Richard; the ensign-staff of Richard was shot away during the firefight and its flag disappeared into the sea.

Because of the light wind and the shortage of officers and crew onboard Richard, Serapis easily out-sailed the Yankee warship. The enemy’s advantage became obvious and was improved by keeping to Richard’s stern allowing for raking fore and aft. The French Army colonel who was stationed upon the poop deck lost almost all of his men. He abandoned that station and took the survivors to fight from the quarterdeck. Serapis, located under Richard’s stern, infuriated Jones, but there was little that he could do. Richard’s men fell here and there throughout the ship. Meanwhile the American topmen kept an incessant and well-directed fire into the enemy’s tops. Apparently effective, from Jones’s perspective it was the only positive aspect of the battle.

The commodore now issued orders to extricate the American ship from the bloody scene. It became apparent that if the battle lasted for another half hour, the enemy would likely have slain nearly all Richard’s officers and men and would have been compelled to yield to a superior force. At this critical moment Jones ordered the ship’s acting sailing master, Samuel Stacy, to bring Richard around.[9] As Serapis passed across the ship’s bow, Richard’s braced main and mizzen topsails swelled from a sudden fresh breeze from her stern. The Yankee vessel shot ahead, crossing the enemy ship’s bow and becoming entangled with Serapis’s mizzen shroud and the rigging on her starboard side.[10] Excited, Jones cried out, “Well-done, my brave lads, we have got her now; throw on board the grappling-irons, and standby for boarding.”[11] This was accomplished, but the enemy promptly cut the lines fixed to the grappling irons. More irons were thrown onboard and this time many grapples and lines held on. The Yankee’s crew successfully hauled the enemy’s ship snuggly alongside. Serapis’s jib-stay was cut away aloft and fell on Richard’s poop deck where Jones and Stacy were stationed. They attempted to fasten it to Richard’s mizzenmast. Frustrated, Stacy cursed, but Jones admonished the sailing master saying, “It is no time for swearing now, you may by the next moment be in eternity; but let us do our duty.”[12]

The wind ceased to blow, but a strong tide pushed the ships now locked together toward the town of Scarborough. Pearson realized that he could not extricate Serapis, so he dropped one of his anchors. His strategy was to try to cut Richard adrift, allowing the current to take the badly damaged vessel toward shore, giving the British seamen time to regroup. Forty minutes had passed since the action had started. The small arms fire from the tops continued without interruption, their muskets, blunderbusses, swivels cohorns, and pistols silencing the British topmen except for one enemy foretop sailor. He kept peeping out behind the head of the foremast and firing into the American tops. As soon as Fanning saw where the fellow was hiding, he ordered a marine to hold his fire and wait until he could get his gun sights directly on him. Shortly thereafter the marksman shot the prowling sailor with his musket and the man fell from aloft onto the forecastle deck far below.

Both ships remained tethered together, positioned with the bows of each locked next to their opponent’s stern. This meant that the heaviest cannon that both vessels carried amidships at their respective tumblehomes could not be used because it was impossible get to their muzzles to sponge and reload. Therefore, both adversaries resorted to boarding and fighting hand to hand. A succession of attacks and counter-attacks followed and many additional lives were lost on both sides.

Serapis’s anchor held fast to the ocean’s bottom as the two intertwined vessels, in a seaborne clinch, laid about three nautical miles east by south of Flamborough Head. The Continental Navy Brig Vengeance and the small tender that Jones had left behind with one officer and twenty men were about one and a half miles astern of Richard, but neither took the risk to come to her assistance. Since Fanning and his fellow topmen had silenced the enemy’s tops, Richard now directed its fire down upon the opponent’s decks and forecastle. This operation proved quite successful. In about twenty-five minutes Serapis’s decks were clear of men. There were sailors still below and they kept up a constant fire from four of their starboard bow guns under cover of the forecastle. These cannon produced a great deal of damage to Richard. Her larboard (port) guns were of no use because of the position of the two ships.

Several of the shot-damaged sails that hung limply over the quarterdeck of Serapis caught fire and the flames climbed into her tarred rigging. Since both vessels were entangled it spread, endangering both ships. The battle action stopped while the two contending parties extinguished the blaze. Once accomplished, the gunfire resumed. Richard’s topmen now took possession of the enemy’s top platforms since the vessels’ yards were lodged within each other. Richard’s topmen threw with stinkpots—flasks of combustible material—and hand grenades among those few enemy sailors who appeared below. As the battle reached its third hour, Richard’s topmen took control of Serapis’s quarterdeck, the upper gun deck and the forecastle. Jones became confident that the enemy would soon strike her colors when the unexpected occurred.

Richard had about five feet of water in her hold and was in danger of sinking. Rumors began circulating that Jones and all his principle officers had been killed and it was unclear who was in command of Richard. Some crewmen asked a gunner, the ship’s carpenter and the master-at-arms to go on deck and ask the enemy for quarters in hopes of saving those who were still alive from being shot or drowned. The three men scrambled topside, displayed a crude white truce flag on the quarterdeck and loudly bellowed, “Quarters, quarters, for God’s sake, Quarters! Our ship is sinking!”[13] They then moved to the poop deck to haul down the Stars and Stripes. When Fanning heard the plea in the top, he assumed that it had originated from Serapis and told his men that these cries had to be British sailors begging for quarters. Meanwhile the three American seamen on the poop deck discovered that the ship’s flag along with the ensign-staff was gone. They returned to the quarterdeck and once again loudly pled for quarters. Suddenly an even louder voice emanated somewhere below from the disgruntled commodore, “Quarters! What damn rascals are them? Shoot them-kill them!”[14] Jones stood upon the forecastle, having just fired his pistols when the crewmen appeared on the quarterdeck. The carpenter and the master-at-arms, hearing Jones’s authoritative voice, hurriedly went below. The gunner, however, dawdled. Jones threw both empty pistols at the sailor and one struck him on the head. The gunner fell down the gangway ladder to the deck below and remained there semi-conscious until the battle ended.[15]

Both ships continued to fire at each other at point blank range and still another fire broke out. Once again, an inferno climbed the entangled rigging of both ships and British and Yankee crews busily fought the blaze, causing the canon and musket fire to temporarily cease. The flames now reached high aloft and set Fanning’s maintop ablaze. It was very difficult to fight the fire because of the height above the deck. The water they had with them in casks was for hydrating the men, but they threw it on the flames without result. Next, they removed their jackets, threw them onto the fire, then stomped upon the clothing to smoother the firestorm. This desperate strategy was successful. Once the emergency appeared under control, the enemy demanded to know if the Americans had in fact struck since three men had earlier pled for quarters. They demanded that Richard’s pennant be hauled down as a surrender gesture, but noticed that the ship’s flagstaff was missing.

Jones replied, “Ay, ay, we’ll do that when we can fight no longer, but we shall see yours come down the first; for you must know that Yankees do not haul down their colors till they are fairly beaten.”[16]

The ferocious combat resumed until a third cry of fire was heard from both ships. All hands once again extinguished it and the pitched battle renewed. Muskets and smaller guns blazed away; hand grenades and stinkpots filled the air making it almost impossible to fight on deck. Therefore, men grabbed pikes and boarding axes and attacked each other hand to hand through the ship’s large gun-ports. The muzzle-loaded cannon that had been run through the ports had become useless because there was insufficient room to properly operate them.[17] Still Serapis’s heavy shot did a great deal of damage, breaching Richard’s oak hull in several places. The Yankee’s rudder was badly damaged and many of her remaining gun-crews were wounded or killed.

A dazzling moon illuminated the night’s battle scene. The Continental Navy warship Alliance finally sailed into the skirmish by rounding the stern of Richard and the bow of Serapis. Alliance fired a grapeshot broadside at both ships, but most of its damage was done to Richard. Some of the men onboard Richard in fact believed that she was a British man-of-war that had joined the fray. Alliance changed course, returned to the two stricken ships and inexplicably fired another broadside into Richard’s bow, wounding many more Americans. The bright moonlight made it quite easy to distinguish between the two vessels. Richard was painted black while Serapis had yellow sides causing Jones to suspect that his ship was being intentionally attacked. Alliance kept her position and her captain, Pierre Landais, ordered yet another grapeshot broadside fired that caused more havoc onboard the commodore’s vessel.[18] In desperation Jones ordered three lighted lanterns arranged in horizontal line, hoisted aloft in the fore, main and mizzen shrouds on the larboard side. This was the commodore’s signal to identify Richard as a friend rather the foe. It had the desired effect and Landais ceased fire.[19],

At half an hour after midnight, one of Fanning’s men tossed a grenade from the maintop with the intention of hitting a group of British sailors who were huddled together on the enemy’s gun deck.[20] The explosive struck the combing of the nearby upper hatchway, rebounded and fell between the decks. It detonated and, in doing so, ignited a quantity of loose powder that had been scattered about the ship’s cannon. A huge explosion ensued within a confined space and killed or wounded about twenty sailors. In a turnabout the British seamen now pleaded for quarters, much to the dismay of Captain Pearson. Only a few minutes passed before the captain of Serapis ordered a crewman to ascend to the quarterdeck and haul down the British flag. He refused—telling the captain that he was afraid to expose himself on deck because of the musket fire that was continuously raining from aloft. Pearson then took it upon himself to ascend to the quarterdeck and haul down the ensign that he himself had nailed to the flagstaff at the beginning of the battle, the very flag he had sworn to his principle officers that he would never strike to the “infamous pirate,” John Paul Jones.

Now that the enemy’s flag had been struck, Jones ordered his first lieutenant Richard Dale to select a number of crewmen to take possession of the prize. Regrettably several of Richard’s men were killed by the British onboard Serapis after she had struck to the Americans. They meekly apologized afterwards, saying the men had breached honor among combatants because they were unaware that their warship had struck her colors. This ended the memorable four-hour battle under moonlight. The captain and the surviving officers of Serapis came onboard the badly battered, leaking Richard. After meeting Jones, Pearson ceremoniously presented his sword and said, “It is with great reluctance that I am now obligated to resign you this, for it is painful to me, more particularly at this time, when compelled to deliver up my sword to a man who may be said to fight with a halter around his neck!” Jones accepted his sword and replied, “Sir you have fought like a hero, and I make no doubt but your sovereign will regard you in a most ample manner for it.”[21] Captain Pearson then asked Jones what country supplied most of the crew. Jones answered mostly Americans. Shortly thereafter Pearson’s officers surrendered their side arms to Lieutenant Dale. A brief conversation followed during which the defeated British captain noted that the Americans had fought equally as bravely as his own men. The two captains withdrew to Jones’s cabin and drank a glass or two of wine together.[22]

Ultimately Richard was so badly damaged that she sank and Jones transferred his own crew and the captive crew to Serapis. Sometime later they arrived in Holland and Pearson and his crew were released. Fanning noted that Jones had ordered all of Pearson’s personal belongings packed into trunks and sent ashore with a lieutenant. Pearson returned the trunks condescendingly saying that he would not accept his articles delivered to him from the hands of a rebel officer. The British captain indicated, however, that he would receive the articles from Capt. Denis Cotteneau of the Pallas who held a naval commission issued by the French king, a nation recognized by the British. In spite of the slight, Jones asked the French captain to have Pearson’s trunks, sword and pistols rowed ashore and to give them to the defeated Captain Pearson. Cotteneau performed this task and, when he returned back to Captain Jones, he commented that Pearson graciously receive the articles, but did not opt to thank Jones; vanity and incivility trumped courtesy and chivalry.

[1]Bonhomme Richard formerly was the French Naval warship Duc de Duras. Fanning referred to Jones’s vessel as Good Man Richard in his memoir that described the events of the ensuing battle among other personal experiences.

[2]The courses are the lower most sails on the mast. They are raised during a battle for visibility and so as not get in the way of men that may have to fight on deck. The color was a white flag with a red cross across it and the union as its canton. It was also known at the time as a white squadron ensign.

[3]This red flag was the first national flag of the English colonies. It was widely used on all British ships during the colonial period and Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown under this flag.

[4]Fanning consistently misspelled Captain Pearson’s name as Parsons in his text.

[5]This was a fundamental violation of leadership. A commander must never leave his men in a vulnerable position to engage in battle.

[6]To support his intended raids, Jones initially embarked with one hundred thirty-seven marines aboard Bonhomme Richardinstead of the usual sixty to provide security and musketry support normally assigned to a warship of that size. These were not Continental marines, but rather members of France’s Irish Regiment of Walsh-Serrant, whose watchwords Semper et Ubique Fidelis—Always and Everywhere Faithful) became the basis for the motto of the United States Marines. Col. Antoine Félix Wuibert (Weibert) was in charge of Bonhomme Richard’s principal battery, the 12-pound guns on the upper deck, which were to fire split shot into Serapis’ rigging in order to disable it. The Irish marines were sent to the poop deck and fighting tops (the highest parts of the masts) to fire down upon the enemy ship. Jones referred to another Frenchman, Colonel de Chamillard, who commanded twenty soldiers on the poop deck. John Paul Jones, Memoirs of Rear-Admiral Paul Jones(New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1972) 1: 184.

[7]Fanning, Fanning’s Narrative: The Memoirs of Nathaniel Fanning (Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1913), 36.

[9]Fanning’s description of how the maneuver was accomplished is complex and difficult to follow, but not a crucial part of the story. It was a remarkable feat of seamanship accomplished while the ship was receiving fire with many of her seamen killed or injured.

[10]Shrouds are pieces of standing rigging which hold the mast up from side to side.A vang is a rope or tackle that extends from a boom to a deck fitting of a vessel in order to keep the boom from riding up.

[11]Fanning, Fanning’s Narrative, 38.

[12]Ibid., 38. This meant that one should not carelessly close the doors to heaven at a critical time.

[15]A trepan was used to relieve the fluid buildup in his skull and he recovered.

[16]This is the origin of the well–known Jones rejoinder, “We have not yet begun to fight.” His exact words are unknown and in dispute, but regardless the sentiment is the same.

[17]Fanning, Fanning’s Narrative, 42.

[18]“After the battle Landais confided to one of the French colonels that his intention was to help Serapis sink the Richard, to capture and board the British frigate and emerge victor of the battle. Later he had the impudence to claim that his broadsides forced [the Serapis] to strike.” Samuel Eliot Morison, John Paul Jones, A Sailor’s Biography (Boston, MA: Little Brown, 1959), 235.

[19]Other historical documents suggest that in spite of Bonhomme Richard’s highly visible lanterns, Alliance closed once again to engage the two ships and Landais ordered another grapeshot broadside to be indiscriminately fired.

[20]Fanning, Fanning’s Narrative, 43.

[22]Although Richard Pearson eventually surrendered, he accomplished his mission of protecting a convoy of merchant ships that, with only one exception, escaped capture by John Paul Jones’s squadron. Pearson ultimately was awarded a knighthood in spite of the loss of his ship and crew to the upstart Jones.

5 Comments

Very exciting retelling of an exciting and infamous battle. Samuel Eliot Morison’s 1959 Pulitzer Prize winning book, “John Paul Jones A Sailor’s Biography” presents a more self-seeking explanation regarding Landais’ motivations for firing on Jone’s ship the, Bonhomme Richard. Captain Jones was treated abhorrently all around. I highly recommend Morison’s book.

Great article. I fly the Serapis ensign on my home.

Well done! You have brought Nathaniel Fanning’s diary alive. The best description of naval warfare since Patrick O’Brian, and yours is 100 percent authentic. Where can we get more of your work? Thank you. Phil Giffin – Wyoming

How did Jones’s ship the “ Bonhomme Richard” get within hailing distance of “HMS Serapis” without the latter opening fire? The answer was Jones used a commonly used deceptive ruse to close the distance with the superior Serapis. Jones’s ship could not be identified because they displayed British colors. Then just before engaging, Jone’s pulled down the British colors and raised the colors of the American rebellion.

Ref: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/bonhomme-richard-frigate-i.html

Very interesting account of the battle. I have information from an account of a 9yr old Midshipman on the Seraphis that the prisoners were imprisoned in France & the prison governor was called Comyn, because of his age the governors wife was most kind to him & had him educated. His father paid a ransom & he returned home.

Are there any records of where this prison would have been ?

Thank you for your attention.