We recently received a demonstration of an exciting virtual-reality experience designed to teach middle and high school students about one of the key events leading to the American Revolution, the burning of HMS Gaspee in Rhode Island. The project’s creator, Adam Blumenthal, professor of the practice of computer science at Brown University, discussed the project with us.

You’ve been working on an innovative project to teach young people about the burning of HMS Gaspee in 1772. Tell us a little bit about it.

Virtual reality is a computer technology that creates the experience of being somewhere else. It’s a technology that can have a powerful impact on learning. We have an epidemic in American schools: most students, especially in high school, are not engaged by the ways we teach. Students today, and for the past few decades, are “digital natives,” they’ve had computers in their lives for most of their lives. Digital natives have different brain wiring, and they process information in ways different from previous generations. Burning the Gaspee VR is an effort to engage learners with a very compelling new format—virtual reality. We tell the story of the Gaspee as very rich, immersive, interactive, audio-visual experience with artifacts, simulations, and a feeling of being there.

This is a very interesting technology. Will it be available only to places with specialized technology?

There’s a virtual reality format called Google Cardboard. It’s literally a little cardboard box with two lenses and a pocket to hold an iPhone or Android smartphone. The user holds it up to their eyes and their vision of the real world is replaced with a digital world. As you move your head up, down, and all around you see you’re in a digital environment, and you can control your actions there. The Gaspee VR project is using this platform to make it very accessible.

The Gaspee story is a very important aspect of the onset of the American Revolution, but there are many other important events to choose from. What drew you to the Gaspee story?

The first thing that drew me to the Gaspee story is the locality of it. In December 2015 my wife and I moved back to Rhode Island after being away for fifteen years. I first encountered Gaspee historic markers in a few places in my neighborhood and then all around Providence and the state. I became curious about the story. And it’s a really interesting, great story, so that drew me in further. Then there are many interesting artifacts from the event and the period that are accessible. I love working with historic primary source materials, and many groups around Rhode Island were very generous to share their materials and knowledge. Lastly, I got that curious sense of Rhode Island pride that we have about this brave attack against Colonial injustice, “18 months before the Boston tea party!” I want the attack on the Gaspee and the dotted line from that to the Declaration of Independence to be better known on the national stage. I thought with the “wow factor” of VR it might help the story become better known.

As you developed the narrative used in this simulation, did you learn new things about the Gaspee affair?

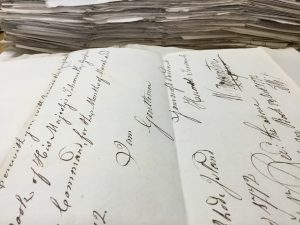

I love to refer to primary source materials, and integrating them into a digital world creates a really neat look. So I had the chance to read original letters exchanged between all the main players in the story. I saw records and artifacts written by these people from the 1770s who were like celebrities in my mind—General Wanton, Admiral Montagu, John Brown, Stephen Hopkins. One of the things I got out of that research was a moment of sympathy for the main antagonist in the story, British naval officer, Lt. William Dudingston, captain of the Gaspee. After he was shot, his crew was captured, and his ship was burned, Dudingston was taken to the home of a loyalist to recover. I held and read the first letter he sent after being captured. Sent to his superior officer, Admiral Montagu in Boston, the handwriting was shaky, he describes the pain he’s in, and his usually grand signature was flimsy. Then Montagu writes a terse letter to Rhode Island Gov. Joseph Wanton, with emphatic language referring to “the piratical proceedings of the people of Providence.” One of the artifacts I found, which I had not seen reference to in the past, was the weather report for the day of the attack, June 9, 1772. I contacted someone I know at NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center, the keepers of many of the climate and weather reports recorded during the history of the United States. They happened to have the weather journals of Ezra Stiles and his wife Eliza, from Newport. They were diligent about documenting weather conditions in comprehensive daily journals with a thermometer “procured by Dr. Benj. Franklin in London.”

Is there any one facet of the Gaspee story that you’d like to make sure everyone is familiar with—whether it be the background, the event itself, or the aftermath?

What I called the “dotted line from the Gaspee attack to the Declaration of Independence”—King George III, upon learning of the attack, sent a Royal Proclamation to Governor Wanton. He offered a huge bounty for the attackers, and also declared that the accused would be put on ships and sailed to London for trial. They probably would not have gotten a fair trial and likely would have been found guilty of treason and attempted murder. So British naval vessels arrived in Newport, ready to take the accused to London. When the proclamation arrived, four Rhode Island leaders sent a letter to Samuel Adams in Boston, to make him aware of this Royal directive to try the colonists in England, rather than locally among a jury of peers. Samuel Adams took up a keen interest, began a correspondence with Rhode Island leaders, then began a correspondence with the colonial leaders of Virginia, and soon thereafter the eighteenth century secret social network referred to as the Committees of Correspondence was reestablished among all the colonies. Soon momentum developed across the correspondence, and the First Continental Congress was established.

What challenges did you encounter in staying as true to the history as possible, while providing an immersive experience?

The biggest challenge was finding the true story. Over the centuries many different versions have been presented. Some facts stuck because they are true, other details have stuck because they make for a better story, or it’s the victor’s version, or from images in well-known painted depictions. I relied on the best, most recent research out there (including Steven Parks’ JAR Publication, The Burning of His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee), and balanced that with some Rhode Island chest thumping.

Tell us some of the feedback you’ve gotten from young people—and adults—who have tried this virtual reality experience.

There’s an immediate “wow” moment when students enter the experience, which I think opens the students’ minds to being ready to learn. They love the immersive feeling of being there. We used some very cool stylized silhouette-style animations that they really like. And I filmed several re-creations in historic locations with historic interpreters with authentic clothing and objects. Students love the feeling of being in those environments, like a participant in the events.

How should our readers keep apprised of the progress of this project, and the availability of the end product?

There’s an information page at www.CuriousSense.com/Gaspee. People can contact me from that page.

Are you working on any other projects related to the American Revolution or the nation’s founding?

I am working on other history experiences in VR, but not specifically related to the American Revolution. I produced a re-creation of Thomas Edison’s lab from 1879 and a Romeo & Juliet experience. I’m working on some other subjects too.

2 Comments

I am a Fifth grade teacher in Colorado and I teach the Burning of the Gaspee every year. How can I get the VR for this? My kids would eat this up. I am so excited about this I can’t stand it. I will be in Rhode Island from June 21 through July 13th? Can I come see this?

The Gaspee VR app is available here: https://www.gaspeevr.com/