A councilman by profession, James Allen, esquire, lived in Philadelphia during the early years of the American Revolution. A man of considerable social prominence and stature within the colony, Allen held much influence. Indeed, the entire Allen family was held in high esteem, particularly since most of its members enjoyed positions of privilege and respect. Because of this, the position of this family during the Revolutionary tumult is an interesting one. The Allen family believed that an established form of government was necessary to safeguard against unrest; they were, however, also Americans and because of this they had much sympathy for the Revolutionary movement and the principals behind it. Despite this, the Allens would not support an armed uprising against the Crown; that was where they drew the line and it is there where their support shifted toward the British.

In his diary, James Allen recorded events he deemed noteworthy between 1770 and 1778. In the beginning of the diary, he stated the journal’s purpose as being for the amusement of future readers as well as to serve as a medium of thought perseverance due to the writer’s nature of forgetfulness concerning events of his past, something he regretted. The diary is riddled with private anecdotes surrounding the writer’s life, such as the death of friends, noteworthy dinner guests, and personal ailments. The diary also holds first-person accounts regarding events surrounding the Revolutionary period.

On the morning of Thursday, December 19, 1776, a party of soldiers, their bayonets fixed, surrounded the house of James Allen. He got up and upon answering the door was met by an officer who produced a warrant dispensed by the Council of Safety ordering his seizure and trial before the Council in Philadelphia. Reluctantly, he went, and discovered the reasons for his summoning.

Mr Own Biddle [A member of the Council of Safety] then said, that they had received accounts of the unwillingness of the Militia of Northampton County to march, that they knew my influence and property there, & were afraid of my being the cause of it, & added that my brothers being gone over to the enemy the publick would expect that I should be put on my Parole & hoped I wou’d have no Objection to stay within six miles of Philad.[1]

Allen faced house arrest. In a particularly unexpected and baffling turn of events, Allen admitted to not supporting the cause of liberty. What caused him to essentially admit guilt is open to contemplation. He rationalized his confession by stating that while he did not support the cause of liberty, he never publicly interfered with it. He then, “produced some certificates which I had the precaution to procure, testifying the truth of the above[2]” before asking the council members to dinner that same evening. Amazingly, they agreed. Not only did they agree, they released Allen with no guard, trusting that he would return for dinner, and return he did.

In his journal, Allen stated that the mission of the dinner included defending his brother’s conduct for joining the Loyalist cause. Allen raised some very good reasons why someone should not support the cause of liberty. His reasons were so well met, they even convinced members of the Council of Safety to drop all accusations levied against Allen and his brother.

His rationale went like this:

I drew a picture of the state of the province, the military persecutions the invasions of private property, imprisonments & abuses, that fell to the share of those whose consciences would not let them join in the present measures. I particularized two of their own Ordinances authorizing field officers to invade & pillage our houses & imprison our persons on mere suspicion & concluded by saying, that I was almost frightened into a determination of seeking the same protection, that my brothers had done. Mr. Biddle acknowledged the truth of what I said & excused the necessity of the present arbitrary measures, by the divided state of America. I told him conciliatory measures would make more converts; that it was hard to forget we were once freemen, who had lived under the happiest & freest Government on earth; & I believed these violences inclined a majority of the people to wish for General Howe’s arrival[3]

This argument satisfied the councilmen so much so that,

In the afternoon, they produced a certificate, which they hoped I would not object to; wherein they set forth, my brothers departure & the backwardness of our Militia as reasons for sending for me, that I had given them satisfaction respecting my prudent conduct, that my conduct did not appear unfriendly to the cause of Liberty, nor inconsistent with the character of a Gentleman; & I in return pledged my honor verbally not to say or do anything injurious to the present cause of America . . . so we parted amicably[4]

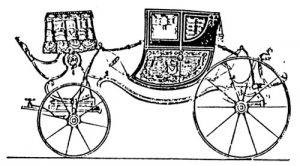

This ended James Allen’s brush with trouble for the moment, but not for good. Roughly a week later, Allen had another run in with liberty’s proponents. This occurred when Allen’s wife went to visit a friend, accompanied by her daughter in their chariot. They were accosted by a group of Patriot militia. The soldiers beat the driver before pointing their bayonets in his direction. In self-defense, the driver made ready use of his whip. “This so enraged them, that they pushed their Bayonets into the Chariot, broke the glass & pierced the chariot in 3 places; during the whole scene begging to be let out & the children screaming; they also endeavored to overset it, while they were within it . . . their design was to destroy the Chariot.[5]

Coming to the defense of his family, Allen confronted an officer of the militiamen who “attempted to draw his sword on me.”[6] It is unclear what happened next. The writer left the rest out, but managed to survive the encounter to jot it down in his diary.

He concluded his entries with a description of his experiences in colonial Pennsylvania at the time of majoritarian insurrection:

This accident [referring to the violent provincial officer defending his belligerent men] has disturbed my peace, as I for some time expected the violence of the people, inflamed by some Zealots would lead them to insult my person or attack my house. But as nothing of that kind has happened, I grow easy & hope it has blown over. To describe the present state of the Province of Pennsylvania, would require a Volume. It may be divided into 2 classes of men. Those that plunder and those that are plundered. No Justice has been administered, no crimes punished for nine months. All Power is in the hands of the associators, who are under no subordination to their officers. Not only a desire of exercising power, in those possessed of it, sets them on, but they are supported & encouraged. To oppress one’s countrymen is a love of Liberty. Private friendships are broken off, & the most insignificant now lord it with impunity & without discretion over the most respectable characters.[7]

Allen’s diary reveals a story of a man who, through a talent for communication, managed to talk his way out of a very serious situation. He did this so expertly that he even gained the security of his brother from the hands of his persecutors. The diary records the experiences of a Loyalist man caught in a war he did not support. What his experiences reveal is the violent and coercive nature of the American Revolutionaries, a group who were not above employing violence for the “cause of Liberty.” This violence was not restricted to fighting men, but rather to entire families including women and children. It can be said, for the Loyalists, there was certainly no civility employed by the rabble in arms who, in this case, abused their newfound power.

[1]“Diary of James Allen, Esq., of Philadelphia, Counsellor-at-Law, 1770-1778,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography IX (1885), 193.

2 Comments

My 5X great grandfather, John (Johann Wilhelm) Griesemer, was Allen’s neighbor in Northampton Town (now Allentown, PA). He was also a member of the local Committee of Observation and Inspection.

There were also Loyalist militias, who did exactly the same kinds of things to Whig/Patriot families. I am a direct descendant of at least 3 members of “Delancey’s Cowboys” in New York. This loyalist light calvary militia terrorized patriot families, burned their homes, stole their horses and cattle, etc.

A revolutionary war is the absolute worst kind of war. They literally turn neighbors into enemies; family members against family members, etc. Passions run high, and atrocities abound.