“There, rebels, there is a cage for you.”[1]

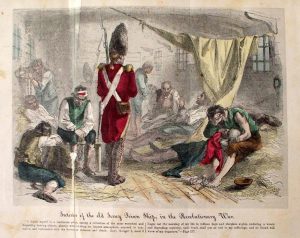

Forced to row under guard of British marines, a boatload of captured American sailors approached the forbidding black hulk of the old British warship, HMS Jersey. Nicknamed “The Hell Afloat,”[2] the Jersey and other decommissioned British warships were moored in Wallabout Bay, just off Brooklyn, New York, where they served as floating prisons for captives taken at sea by the Royal Navy.

In one of the small rowboats sat “universally detested” David Sproat, a Loyalist who had been named Commissary of Prisoners and whose responsibility it was to oversee the captives.[3] As they approached the prison ships, Sproat gloated about the imminent confinement of his rowing prisoners.[4]

One of the men rowing Sproat’s boat was Capt. Thomas Dring, a twenty-three-year-old American sailor captured off the privateer Chance from Rhode Island. As Sproat exulted at the sight of the filthy, black hulk looming before them, Dring quickly averted his eyes—but not before catching sight of the shuffling masses of imprisoned men moving about the upper deck in the twilight.[5]

Decades after surviving their imprisonment aboard the prison ships, many men in writing their memoirs recalled their immediate impressions upon seeing the Jersey for the first time.

The Jersey was a gigantic sixty gun warship built in 1736 that had been converted into a hospital ship in 1771. In 1779, being repurposed from a warship to a prison, the Jersey had been stripped of almost all sails, spars and rigging. “Nothing remained but an old, unsightly, rotten hulk. Her dark and filthy external appearance perfectly corresponded with the death and despair that reigned within.”[6]

The derrick and bowsprit, however, remained intact, their skeletal outlines extending from the decaying carcass of the Jersey like bones picked clean by carrion birds. Typically used for hoisting supplies on deck, the derrick stood out from the blighted hulk, putting prisoners in mind of a gallows.[7] Captain Dring saw men clambering out upon the bowsprit, in a desperate bid to temporarily escape the close confines of the decks and perhaps savor a momentary breeze.[8]

The Jersey’s portholes had all been sealed shut. Iron-barred breathing holes were drilled the length of the ship about ten feet apart.[9]

Ebenezer Fox, imprisoned on the Jersey as a seventeen-year-old in the late spring of 1781, recalled that, “The idea of being a prisoner in such a place was sufficient to fill the mind with grief and distress. The heart sickened, the cheek grew pale with the thought.”[10]

It was now sunset and Captain Dring and the other prisoners had reached the Jersey. A sickening miasma emanated from the ship. The men whom Captain Dring had glimpsed shuffling on the deck had tasted their last breath of fresh air for the evening and were now locked down below, in the fetid, suffocating hold of the ship. Captain Dring happened to be facing one of the airholes which dotted the side of the ship and out of which “came a current of foul air . . . with accumulated nauseousness which it’s impossible for me to describe.”[11]

Prisoners locked within the hold called out to Dring and the others through these airholes. One prisoner, whose face Dring couldn’t see in the gloaming, expressed regret that such young, healthy men were about to join the ranks of sick and starving sufferers aboard the Jersey. Captain Dring recalled that the man told him that, “Death had no relish for their skeleton carcasses and that he would now have a feast upon fresh comers.”[12]

To be imprisoned on the Jersey was to inhabit a hell on earth of sickness, contagion, and misery. Once on board, the health of a prisoner was doomed to deteriorate due to a myriad of factors—rampant disease, rotten food, contaminated water, infestations of lice, and suffocating heat or frigid cold. According to prisoner Thomas Andros, who had been captured on the brig the Fair American in 1781, the Jersey“contained pestilence sufficient to desolate a world; disease and death were wrought into her very timbers.”[13]

Every evening at dusk, the prisoners were herded below deck. The clang of the grate as it closed over the hatchway behind them signaled the start of yet another hellish, interminable night. Allowed no fire or light, the prisoners languished in darkness. Though unable to see each other, the moans and lamentations of suffering men comprised a perpetual and maddening cacophony, haunting what few precious moments of rest a prisoner could steal. “But silence was a stranger to us. There was a continual noise during the night . . . some the effects of pain and some from delirium but mostly the effects of heat or suffocation.”[14]

Any attempt at finding comfort below deck proved futile. Desperate for fresh air, Captain Dring often competed with other prisoners to find a place to sleep near the barred breathing holes. Lying down along the sides of the ship “not only secured us from being trod upon by night but also afforded a breathing place, which was very desirable, particularly by night when the nauseous smell was scarcely to be endured.”[15]

Locked in the netherworld of the hold, the men who were still somehow clinging to health were intermingled with gravely ill and dying men. Contagion and illness were simply inescapable. “All the most deadly diseases were pressed into the service of the king of terrors, but his prime ministers were dysentery, small-pox, and yellow fever.”[16]

Dysentery

Of the hundreds of men confined in the hold overnight, only one or two men at a time were ever permitted to climb up on deck during the night. The most pressing reason to ascend would be to relieve oneself—which, owing to the rampant disease on the Jersey, often took on an unprecedented urgency.

Prisoner Christopher Hawkins, who was about seventeen years old during his imprisonment, recalled that “We had a great deal of sickness on board the Jersey, and many died on board her. The sickness seemed to be epidemic and which we called the bloody flux or dyssenterry.”[17]

Dysentery, a highly contagious disease often spread by contaminated food or water, resulted in severe stomach cramps and uncontrollable, bloody diarrhea. According to Christopher Vail, who was confined on the Jersey in 1781 at age twenty-three, “many of the prisoners was troubled with the disentary and would come to the steps and could not be permitted to go on deck, and was obliged to ease themselves on the spot, and the next morning for twelve feet round the hatches was nothing but excrement.”[18]

Hawkins echoed Vail’s complaint. “Only two prisoners were allowed to visit the upper deck at the same time in the night let the calls of nature be never so violent, and there was no place between decks provided us to satisfy those calls. This induced an almost constant running over me by the sick, who would besmear myself and others with their bloody and loathesome filth.”[19]

Captain Dring, during his time on the Jersey, could at least avail himself of the “necessary tubs” that had been placed below deck—but the tubs proved noisome “and it was with difficulty they could be reached . . . in utter darkness, particularly as we had to tread over many who were strewn along the deck to sleep, though all had avoided, as far as in their power, a place of repose near those tubs.”[20]

Yellow Fever

In addition to dysentery, prisoners were also susceptible to the mosquito-borne illness yellow fever. Thomas Andros recalled the horror of trying to sleep below deck amidst men in the throes of fever and accompanying delirium. At any given moment, according to Andros, the man sleeping next to him “would become deranged and attempt in darkness to rise and stumble over the bodies that every where covered the deck.”[21] In an effort to prevent the man from roaming deliriously through the hold, stepping on others and adding to the chaos, Andros said he would “hold him in place by main strength.”[22] If his exertions failed and the man was able to rise, Andros would be forced to “trip up his heels and lay him again upon the deck.”[23]

Sometimes, a man in the grip of delirium might manage to break free from the grasp of his well-intentioned bedfellows and restlessly wander, disoriented and hallucinating, through the hold. Or even worse, slashing and swiping with a weapon. “To increase the horror of the darkness that shrouded us, (for we were allowed no light betwixt decks,) the voice of warning would be heard, “Take heed to yourselves. There is a mad man stalking through the ship with a knife in his hand.”[24]

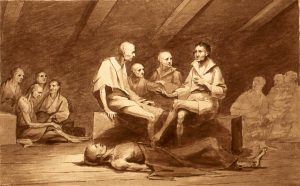

Other times, the man sleeping next to Andros would prove to be preternaturally still and silent during the night. Only in the morning would Andros find that the man beside him was not sleeping, but dead.

Smallpox

Captain Dring passed his first night on the Jersey in misery. Finally, the desolation of night gave way to the slow creep of dawn and sunlight filtered into the hold. The hatches sprang open, and Captain Dring and the other prisoners, in anticipation of moving about the deck for the day, climbed out of the darkness.

As the sun rose higher in the morning sky, it flooded the Jersey’s deck with light and illuminated the faces of his fellow prisoners. Captain Dring suddenly noticed a nearby man whose flesh bore the unmistakable signs of smallpox. He quickly scanned faces of the other men around him and realized, with dawning horror, that he was “surrounded by many with the same disorder.”[25]

Ichabod Perry, though confined on a different prison ship in Wallabout Bay, also endured an outbreak of smallpox. “To add to our misery, we soon got the smallpox among us, which was some alarming, as but few of the prisoners had ever had it . . . All that was taken with it soon died . . . I put the vituals [sic] into a fellow’s mouth (which was the last he ever ate) who was blind with the smallpox but I did not take it then; our situation had got so hopeless that Death had almost lost its sting.”[26]

Placing food, morsel by morsel, into the mouth of a person infected with smallpox was altruistic indeed, especially considering that part of the progression of the disease is the breaking open of sores in the mouth, spreading large amounts of virus into the mouth and throat.[27]

Rather than risking catching smallpox naturally from one of the other men, Captain Dring decided to inoculate himself against the disease. Inoculation usually, though not always, increased one’s chances of surviving the illness and obtaining the one benefit that smallpox bestowed—the welcome after-effect of lifelong immunity.

To inoculate himself, Captain Dring obtained some “matter” from the oozing pustules of a fellow prisoner he deemed sufficiently “full” with pox.[28] “Having no one to do it for me, it was my task to stand my own doctor.”[29] Using a pin, he scratched the flesh of his hand between the thumb and forefinger. He then loaded the smallpox material into the scratch, and bound it up. The next day, the wound began to fester—a sure sign that the virus had been effectively transferred.

One of Captain Dring’s messmates, a twelve-year-old boy whom he had known on the Chance, was suffering from severe case of smallpox. The boy had been inoculated but the disease took a fierce turn and the prognosis was dire. One night, in the final throes of the illness, the boy suffered extreme agony—writhing and screaming. Captain Dring sat up with the boy in the blackness of the hold and cradled him in his arms until dawn.

Decades later, Captain Dring recalled “This night was truly a painful one to me, most of which was spent in holding him in his convulsed state, and that in utter darkness.”[30] His attempts to soothe the boy were in vain. “It was truly heart-piercing to me to hear the screeches of this amiable boy calling in his delirium for the assistance of his mother and others.”[31]

The boy passed away in Captain Dring’s arms. In the morning, the bodies of the prisoners who died overnight would be ferried to the sandy shore of Wallabout Bay, where they would be hastily interred under a few shovelfuls of sand.[32] Captain Dring wanted to help bury the boy, but could not—by then, he had broken out with smallpox due to his inoculation.[33]

Luckily for Captain Dring, his case of smallpox proved to be fairly light and he recovered fully. At least, his body recovered. His mind, however, still rankled four decades later with memories of the Jersey, the scar on his hand serving as an immutable memento of his imprisonment. Writing his memoir as a sixty-five-year-old man, he mused, “I often since (after a lapse of more than forty years) look at the scar it has left upon my hand. It brings fresh to my recollection the dread upon my mind upon that occasion.”[34]

Two months after his capture, Capt. Thomas Dring was released from the Jersey in a prisoner exchange. On the day of the exchange—hardly daring to hope—Captain Dring and the surviving crew of the Chance waited anxiously to hear their names called. He remembered, “Our hearts beat hard with joy, fear, and apprehensions at the same time . . . My name was soon called, and I cheerily answered “here.” The commissary pointed to the boat. I believe I never stepped quicker. It certainly was to me the most happy moment I had ever experienced in all my life.”[35]

Captain Dring stepped aboard the cartel which would take him home to Rhode Island. But he and the other crew members silently worried that their freedom might be snatched back at the last second and that they would be forced back on board the Jersey. “The very thought of again being put on board the hulk was terrifying to us, and I believe that an event of this kind would have been immediate death to most of us.”[36]

At long last, the prisoner exchange was officially completed. Aboard the cartel, finally free from the horror of the Jersey, Captain Dring looked back at the old hulk. It was sunset, just as it was when he first caught sight of the Jersey two months before.[37] Yet again, he saw the shuffling masses of imprisoned men moving about the upper deck in the twilight, preparing to descend into the hold for the night. But this night, Capt. Thomas Dring would not be among them.

[1]Thomas Dring, Recollections of Life on the Prison Ship Jersey, ed. David Swain (Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2010), 21. Captain Dring’s manuscript was published by Albert G. Greene in 1829 and is available on Google Books. However, in this writer’s opinion, the Greene version of Captain Dring’s story should not be relied upon as Greene substantially re-wrote the work so that it no longer reflects the voice or word choice of Captain Dring. For this article, the manuscript as edited by David Swain has been relied upon.

[2]Ebenezer Fox, The Adventures of Ebenezer Fox, in the Revolutionary War (Boston: Charles Fox, 1847), 96, archive.org/details/adventuresebene00foxgoog/page/n10.

[6]Thomas Andros, The Old Jersey Captive: Or a Narrative of the Captivity of Thomas Andros On Board The Old Jersey Prison Ship At New York, 1781(Boston: William Peirce, 1833), 8, books.google.com/books?id=sTZPAAAAYAAJ&dq=Narrative%20of%20Thomas%20Andros%20on%20board%20the%20Jersey%20Prison%20Ship&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[13]Andros, The Old Jersey Captive, 16.

[16]Andros, The Old Jersey Captive, 12.

[17]Christopher Hawkins, The Adventures of Christopher Hawkins(New York: Privately Printed, 1864), 66, archive.org/details/adventureschris00bushgoog/page/n6

[18]John O. Sands, “Christopher Vail, Soldier and Seaman in the American Revolution,” Winterthur Portfolio, The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. vol. 11 (1976): 53-73, www.jstor.org/stable/1180590.

[21]Andros, The Old Jersey Captive, 13.

[26]Ichabod Perry, Reminiscences of the Revolution (Lima, New York: Ska-Hage-Ga-O Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution, 1915), 16, archive.org/details/reminiscencesofr00perr/page/n5.

[27]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Smallpox Signs and Symptoms,” Cdc.gov, www.cdc.gov/smallpox/symptoms/index.html.

[33]Ibid., 57. Dring also indicates that in addition to his poor health precluding him from attending the boy’s burial, he was unsure if he would have been granted to permission to attend.

[37]In his manuscript, Captain Dring states that he spent almost five months on board the Jersey. But, the extensive research of editor David Swain has revealed that Dring’s imprisonment was actually about two months. According to Swain, “Clearly Dring’s memory, filled with the horrors of the Jersey, stretched out the duration of his imprisonment to fit his concept of the magnitude of those horrors (Dring, xxxiii—xxxiv).

19 Comments

Wonderful job, Katie. Those who survived the winter at Valley Forge — and those who didn’t — have received the lion’s share of our awe and veneration through the years. Perhaps those who gave their ‘last full measure of devotion’ aboard the Jersey and other prison hulks deserve the same.

what an amazing story. These are the stories that should be told in our schools, to help the youth of our country today realize the great sacrifices that even children endured for our country during the Revolutionary War. Remarkable. thank you for writing this piece.

wow, learn something new every day! thanks for bringing attention to a topic of American history that deserves to be much more widely known. so sad what these brave men had to endure!

Wow, just an hour before I saw this online, I had been reading about these same incidents in “The Ghost Ship of Brooklyn” by Robert P. Watson, particularly in Chapter 3, titled “Welcome to Hell”. It is interesting to contrast this account with Watson’s. For those captured by these events, I would also recommend Watson’s book to read the continuing story. Katie, your essay may be similar, but you have developed some details uniquely your own. Thank you!

Ms. Getty, thank you for this informative article which confirmed my worst assumptions about British prison ships. My ancestor William Glenn was captured at the Battle of Brier Creek in Georgia and is said to have died aboard one of those ships. Another ancestor, Preston Goforth, was killed at the Battle of Kings Mountain by his own brother, a Tory. I’ve often thought about how those two deaths were so terrible in their own way. Hard to say which was a worse way to go. And since I’m here in 2019 to talk about them, they obviously had children before they went off to war. Many of the patriot soldiers weren’t just sons – they were husbands and fathers.

At the base of Greenwood Cemetary in Brooklyn there is a memorial to the prison ships victims. They say bones are still rolling ashore. But from that era or recent crimes? Greenwood is a monumental visit for anyone interested in our country’s story

Katie,

Thank you for a very informative and interesting article. I’m currently researching a POW with tenuous links to imprisonment on the Jersey. For those readers interested in disease and its impact recommend the following readings:

For a view of smallpox during the American Revolution:

Elizabeth A. Fenn, Pox Americana: The Great Small Pox Epidemic of 1775-1782 (New York: Hill & Wang, 2002)

For a more macro view of the impact of disease on history and society:

Jarred Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Inc. 1997)

Thanks so much for your kind comments!

Excellent work, Katie, which starkly and graphically conveys the incredibly appalling conditions. Question: what happened to the commissary you mention, David Sproat?

You can read a brief biography of David Sproat here: http://www.kirkcudbright.co/historyarticle.asp?ID=218&p=21

Thanks, Don – interestingly, this is the second British commissary as to whom I’ve seen favorable mention regarding the treatment of American prisoners. Don’t have any idea how reliable the sourcing is regarding Sproat, but the other (whom I’ve been researching) is Commissary General Daniel Chamier – he posthumously received favorable mention in Washington’s correspondence.

Hi Rand, thanks for the kind comment. Not sure if you’ve seen this article, but it seems like an in depth, even-handed treatment of Sproat. https://journals.psu.edu/phj/article/view/25138/24907

Thank you, Katie Turner Getty, for this invaluable catalog of the diseases that haunted prison ships off British-held New York. The article is well-researched and highly informative.

Complicating the accounts of dysentery is the possibility of diarrhea caused by starvation, not by contagion. “Hunger diarrhea,” or starvation diarrhea, is easily mistaken for dysentery.

In the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942, teams of Jewish medical workers, themselves internees, conducted studies of “hunger disease.” At the start of their study, doctors Joseph Stein and Henryk Fenigstein were sure they observed dysentery in starving patients. Bacteriological and serological studies of the waste, however, were negative for dysentery.

Dysentery causes long-term damage. Victims of starvation, however, had intestinal damage suffered “probably in the last days or weeks of life.”

In 1992, R. J. Levin noted that diarrhea is often the “terminal condition” of starvation victims. “While it has often been attributed to bacterial infection, extensive bacteriological studies failed to confirm this and it is estimated that only approximately 15% of cases have a diarrhea of infectious origin.”

Levin conceded that bacterial toxins or viral agents might be play a part in hunger diarrhea. Whatever the involvement of microbes, starvation causes a series of changes that “make the starved intestine secrete excessive amounts of fluid,” “overloading the depressed absorptive function of the colon.”

R J Levin, “The Diarrhoea of Famine and Severe Malnutrition—is Glucagon the Major Culprit?,” Gut, Volume 33 (April 1992): 432-434. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1374053/

Dr. Joseph Stein with the collaboration of Dr. Henryk Fenigstein, “Pathological Anatomy of Hunger Disease,” in Hunger Disease: Studies By the Jewish Physicians in the Warsaw Ghetto, ed. Myron Winick; trans. Martha Osnos (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979), 222-224

Alex de Waal, “Famine Mortality: A Case Study of Darfur, Sudan 1984-5,” Population Studies, vol. 43 (1989): 21 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2174235

John Post, The Last Great Subsistence Crisis in the Western World (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977), 123.

W. E. Roediger, “Metabolic Basis of Starvation Diarrhoea: Implications for Treatment,” Lancet, vol. 327 (May 10, 1986): 1082-1084 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/2871346/

Brian – thank you so much for the kind comment and for the added information and citations regarding the possibility of dysentery actually being “hunger diarrhea”. I wasn’t familiar with that term before now and based on my reading of the prisoners’ narratives and the wealth of citations you were so kind to include – my immediate reaction is that it makes perfect sense. Starvation, rather than contagion. It certainly seems to fit.

Also appreciative that your extremely well-researched article “1776 – The Horror Show” introduced me to famine edema which solved my question of why prisoners were experiencing extreme swelling. Now, knowing the term “famine edema”, it seems obvious.

My next JAR article coming up is called “Walking Skeletons” and it’s about starvation on the Jersey – mostly it describes the condition of the food and the sensory experiences of the men.

Incidentally, the other day Fold3 tweeted out a photo of a Civil War soldier – I believe he had recently returned from imprisonment. The photo was very graphic – he was practically naked and the photo was clearly taken to show the ravages of the starvation he had endured. He literally looked like a walking skeleton. It was very sobering and poignant for me to see the photo and think of the prisoners that we’ve both researched, and realize that they probably looked very, very similar to this man.

Brian, again, thank you for your comment and for the additional info – there is always so much more to learn. Thanks!! 🙂

Katie, thank you for the kind words, and thank you for sharing your diligent research. I look forward to “Walking Skeletons”–what an apt phrase!–and to your upcoming interview on the JAR Podcast “Dispatches.” Those images of emaciated prisoners are compelling.

There is always more to learn, staggeringly. I was stunned to learn that emaciation is not present in the first months of starvation. It’s only in the final, terminal phase. Before emaciation, there is a prolonged period of lethargy. The body tries to save energy. Researchers compared a starving human to a hibernating animal. This phase lasts several months. Atrophy and emaciation become apparent only when death is near, after months of the body’s valiant delaying measures.

My apologies. I feel like Columbo. “Just one more thing….” Emil Apfelbaum-Kowalski, et al., “Pathophysiology of the Circulatory System in Hunger Disease,” in Hunger Disease, page 127.

Thank you for writing this Katie. It’s almost unimaginable to us what these people endured in the pursuit of freedom, wondering if they were going to starve or freeze to death at Valley Forge, and four long years later, if captured be exposed to conditions so appalling that death would be welcomed. It also shows us the exceptional character of George Washington, who refused to follow the inhuman British example.

Thank you, Brian! Have you considered – or perhaps you’re already working on – an article that puts all the pieces together, e.g., the possibility of “dysentery” actually being due to starvation not contagion, the lethargy and later emaciation, etc. I haven’t seen anything similar in the course of my research and I think it would be extremely compelling.

This is fascinating, Katie. Do you think there are mass graves to be found in New York ?

Thanks, Joan! My understanding is that from roughly 1808 – 1908 bones were collected from the Wallabout shore, and eventually placed together in a crypt in Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn – the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument.