Most of the stories told of George Washington are tales of complete fiction. He never chopped down a cherry tree, at least not in the boyhood fashion we have been taught as school children. He was capable of lying, and tactically perfected it on occasion. His elder white hair tied back had not been born on him; he was fair skinned and had chestnut colored hair when he took command in 1775. Other stories abound of his seemingly immortality on the battlefield. It is true that against the better wishes of his subordinates, he would become animated in the heat of battle. His low steady voice would thunder commands of encouragement to his soldiers, all while riding his galloping charger amidst the enemy’s fire.[1]It is true that he had a natural talent for leading, especially in the face of looming defeat. At Brooklyn Heights in 1776, commanding British Gen. William Howe viewed Washington as trapped: pinned between the banks of the East River overlooking New York and the occupied hills to the southeast. Despite requests from his subordinates, Howe was cautious in his approach to the Americans. Under the cover of night and an unusually heavy fog, Washington escorted his army silently across the East River. By the time the British awoke, they discovered the Americans were gone. It seemed that this Mr. Washington was a phantom.[2]The legend of Washington’s ability to stealthily out-maneuver the British was born.

The spring of 1777 had blossomed for the two warring armies in northern New Jersey. Though the weather was finally warming, a major engagement had not transpired since the Continental army had driven the British through the streets of Princeton on January 3rd. With the successes of Trenton and Princeton, Gen. George Washington had wanted to push onward to Brunswick[3], raid the British munitions stores there, and possibly push the British army out of New Jersey entirely. He had been talked out of it by his officers who pointed to an exhausted Continental army, and to the unreliability of depending on the undisciplined colonial militias. With the instability of his regular army wavering day to day, and finding no help from local militias, Washington had to reconsider his plans. His wariness is why he chose to conceal his army for the winter in the hills near Morristown, New Jersey.[4]

Following the events in the first days of 1777, the Continental army did it’s best to stay alive. Rampant desertions threatened to undo what little gains had been made. To keep the soldiers busy, foraging and setting about harassing the British whenever possible became the main objectives of Washington’s men. Knowing that Washington had been shedding hundreds of soldiers as he retreated across New Jersey in late 1776, the British command assumed the Americans were finished. The British then tried to downplay how the American victories at Trenton and Princeton had changed their plans. In April, the British under Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis nearly captured a sizable American garrison under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln near Brunswick. In reviewing captured intelligence, the British may have only learned that the Americans were anticipating the British to move on Philadelphia. In truth, it was no secret what the British intended to do.[5]They figured to attack Philadelphia in the spring of 1777 without much of a fight. Yet the British command remained concerned that Washington would suddenly appear and strike the British rear if they marched west toward the rebel capital.

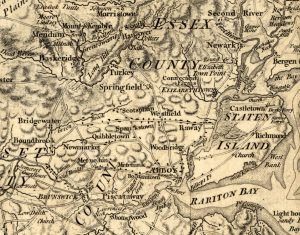

With both armies waiting for the main roads to thaw, the Continental encampment relocated to the stream known as the Middle Brook[6] along the southern foot of the Watchung Mountains by late May. The Continental army built earthworks and used old Lenape trails to spread out its presence within the hills and low mountains. With an established hold on the entire Watchung range, Washington held a commanding view of British positions throughout the region. The repositioning to the Middle Brook had the desired effect of lifting the spirits of the Continental army too. Drilling and training continued, and the Americans were newly equipped with French made munitions.[7]Momentum was taking hold of Washington’s men. As American Gen. Anthony Wayne would write, “We are usefully employed in maneuvering. Our people are daily gaining Health, Spirits and Discipline – the spade & pick axe are thrown aside for British Rebels to pick up.”[8]

The ranks of the Continentals had dramatically improved since mid-February, and now reached some twelve thousand soldiers, though detachments would soon leave to reinforce efforts to combat British Gen. John Burgoyne in upstate New York, leaving Washington with below eight thousand soldiers.[9]The wild swing in enlistments was largely due to the changing seasons, and by the promise of hard coin from local municipalities in exchange for their service. Nevertheless, the events at Trenton and Princeton had finally reached beyond the borders of New Jersey, and inspired many to join. Washington saw a change and found he could rely on local militias to engage British foraging parties too. More citizens had taken to the American Cause as the British army continued their plundering of local supplies. Confidence within the American ranks continued to rise.[10]The Continental scouts sought out unprovoked skirmishes against larger British detachments.[11]It seemed that events were coming to a head.

On June 12th, Gen. Howe moved more than eighteen thousand British troops out of Brunswick in the hopes of creating a feint to lure Washington into battle. After more than a week of the British circling the area, Washington had not budged from the mountains. The Americans picked up intelligence from a questionable British deserter that alerted them to the true intentions of the movements.[12]The diversions of Gen. Cornwallis near Somerset Courthouse and of the force moving near Princeton did nothing to convince the Americans that a major engagement was ripe for the taking.[13]As the British marched, American pickets and swarms of local militia continued harassing the British supply lines and kept the moving columns of redcoats on high alert. Unwilling to show himself, and with British patience wearing out, Washington was now sneered as “a devil of a fellow.”[14] Frustrated, Howe ordered his army to move east toward Amboy.[15]There, they would evacuate to Staten Island. For the British, the decision that the road to Philadelphia would now come by sea – and not by marching through interior New Jersey – seemed to be an easier one by the day.

Anxieties were taking their toll, and the uneasy allegiances of New Jersey citizens, bought by hard British coin, continued to be undermined by British troops foraging for supplies. The artist and now Continental officer Charles Willson Peale remembered on June 22nd that he, “rose early and set off for Kings Town and just arrived in Time, for the Troops were under arms to march to Brunswick – before we Reached that place we understood that the Enemy had decamped – this we understood when we had got within 2 miles of the Town. How solitary it looked to see so many Farms without a single animal – many Houses Burnt & others Rendered unfit for use. The Fences all distroyed and many fields the wheat Reaped while quite Green Others I suppose left for fear of our Scouting parties.”[16]

Washington received reliable reports that the British were evacuating, and sent orders to American Maj. Gen. William Alexander, who was positioned east of the Middle Brook in a swampy area surrounded by short hills, to be ever vigilant.[17]On June 24th, Howe moved his troops out of Amboy and ferried them across the Arthur Kill to Staten Island. In response, Washington finally ordered his main army down into the valley on the southern edge of the Watchung range. This would allow the Continental Army access to the rear of Howe’s retreat. However, it would provide a quick escape route for Washington if he found himself in trouble. Sure enough, with word reaching Howe that evening that Washington was descending into the valley, Howe ordered his entire army to swing around and head back into New Jersey. Peale recalled, “We expected to move down towards Amboy, but early in the morning we understood that the Enemy were moving toward us.”[18]

Detachments of the Continental army continued their advances eastward while Howe’s army had crossed back over into Amboy and were now within two miles of the American scouts. Gen. Cornwallis reached Woodbridge with his forces where he ran into Col. Daniel Morgan’s newly minted Provisional Rifle Corps.[19]The Americans held the British back long enough for runners to send word of their positions. As it became clear that both armies were jockeying towards each other, Washington recalled the main forces, and portions of the army promptly fell back. Cornwallis moved beyond Woodbridge and gave chase to the retreating Americans. The British commander must have thought his chance to “bag the fox” had finally presented itself.[20]Howe was now positioned just to his southwest at Bonhamtown and moving north into a leftward flanking position. The British plan called for an advance through the Scotch Plains area to block off Washington’s escape route. The two separate British columns were hoping to split the Continental army in two, dividing the Americans who hadn’t reached the mountains from those who had, encircle the remaining Americans, and pinch them between the two British generals.[21]

Using a slope of hills to position his division just west of the sleepy hamlet of Rahway, American Maj. Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling, waited to intercept the two approaching British armies. Stirling, a self-proclaimed inheritor of a royal title, had won Washington’s encouragement for showing leadership under fire during the Battle of Long Island. Stirling’s four hundred Continentals had held off the British long enough for the main body of the Continental army to safely retreat to Brooklyn Heights. Now, he was hoping to do the same thing again with a larger body of American soldiers positioned in the path of Cornwallis.

The Americans opened fire on the advancing British columns under Cornwallis just after six in the morning on June 26th. Musket balls ripped through the thick summer air. The smoke from the black powder drifted into the hues of dawn. After a half dozen shots from the American rifles, the Continental line retreated to the first hill where about six hundred Americans awaited the British. Using the cover provided by bushes and trees, the Americans opened fire once again. The British formed a line, and returned with penetrating fire from infantry and Hessian jaegers. The Americans fell back over the hill into the woods. Again, the British advanced and about half an hour later, they came upon a second hill where Stirling was positioned with twenty-five hundred Continental regulars. The Americans opened fire with cannons from a distance of about eight hundred thirty yards before switching to muskets. The British established themselves on each flank of the hill and returned fire with two twelve-pound cannon and numerous six-pounders on their left flank. They attempted a sweeping charge up the hill, but were driven back by relentless American firepower. Cornwallis had his infantry reposition themselves on a right flank. The British intensified their cannon and were gathering their ranks for another charge. Heavily outnumbered, Stirling had few good options. The Americans gave one last blast of cannon into the encroaching British lines before retreating into the surrounding woods. The British gave chase! Stirling lost his horse in the flight to musket fire, and American Brig. Gen. William Maxwell was nearly captured. However, the Americans knew the area far better than the British scouts. Unaware of the exact number of Continental soldiers in waiting, the British were reluctant to pursue the Americans. With the Continental army sliding back into the mountains, the British forces under Cornwallis and Howe finally came together in Westfield, New Jersey.[22]For many of His Majesty’s troops, the missed opportunity to draw Washington into a major engagement boiled emotions over.[23]

In the following days, the British would take it out on the inhabitants of Westfield and plunder much of the surrounding countryside. They marched back to Woodbridge and then on to Amboy where they left New Jersey for Staten Island.[24]As Howe received reports on the engagement at the short hills, his thoughts must have been spiraling with what had gone wrong. The British had foraged the countryside, laid waste to livestock, and undermined the loyalties of residents; all the while taking losses and desertions without a major engagement to show for it. The phantom that was George Washington was now safely at the Middle Brook camp. The fact that both armies remained intact by the end of June left somewithin the British Army to begin questioning Howe’s competence in leadership. As his aide would write, “Because our recent expedition seems to have failed, several rumors are spreading. Almost everyone blames General Howe, but I am convinced that many would have done worse, but none better.”[25]Howe had lost his appetite and was done.The spring campaign was effectively over in New Jersey.

The British abandoned northern New Jersey, and planned to take Philadelphia by way of the Chesapeake Bay further south. This move might have eased the anxieties of his troops, but it did not convince everyone that the British would suddenly gain the decisive blow they much needed. Richard Ketchum writes in his book, Saratoga, “Howe’s failure to act in that spring of 1777 was one matter. Quite another was his unwillingness to recognize that the capture of Philadelphia, beyond its potential psychological impact on rebels and loyalists, could not in itself determine the outcome of the war. In strategic as well as geographic terms, it led nowhere. To win, which is what London expected its commanding general to do in 1777, he must destroy Washington’s army, and seizing a piece of real estate – no matter how valuable – was no way to achieve that.” [26]

Washington’s recognition of this, long before historians would validate it, is what made the difference in New Jersey in 1777. Throughout all of the challenges, and of all of the calls and questions of what exactly was the purpose of the Continental army if not to aggressively engage the British; George Washington proved that the army’s worthiest Cause, above fighting for the Declaration of Independence, was simple survival. The British failure to entice Washington to abandon the stronghold of his eagle’s nest would haunt them for the remainder of the war. It is clear the deception posed by the Continental army had won the foraging campaign in the spring of 1777.[27]For all of the endless posturing and positioning, dip and dab, bob and weave, the knockout Howe had been seeking had never come, and the Continental army’s existence on July 4th, 1777 owed as much to Howe’s underestimation of his opponent and his timid instincts in achieving the British objective as it did to the instincts of Washington’s steady leadership and the guidance his best officers put forth into the struggling American soldier. The sheer feat of maintaining the higher ground in the Watchung Mountains, despite the British controlling the Raritan River and the entire port access to New York and the Atlantic Ocean, had proven to be both the tactical and strategic advantages of the campaign.

The one hundred or so skirmishes and the engagements near Brunswick, Amboy, the Bound Brook and the several short hills beneath the Watchung Mountains in the spring of 1777 tested more than just the resolve of both armies, whom had been slowly festering toward some kind of action that nearly exploded into a full scale battle at the short hills on June 26th. It had tested the commands of both generals. What remains puzzling to historians is that following the astonishing turn of events at Trenton and Princeton, the British showed no urgency to counterattack the Americans. Granted, the winter conditions made eighteenth century warfare undesirable. More so, the British were entirely unaware of just how bad the Americans had it.[28]The mounting reports of the internal struggles facing the Americans did not convince Howe to strike sooner; nor did they give him the courage to risk his entire army to eliminate Washington’s. Howe’s overconfidence led him to underestimate the type of war he was fighting. Backed by the reassurances of commanding the most feared army in the world, William Howe had every right to assume events would play out in his favor. He was wrong.[29]By the time Howe endeavored to make his move, Washington had been reequipped with French munitions, and the growing resiliency of the Continental army that matched the strengthening in enlistments could now harass and frustrate the British without being drawn into a major engagement. Had Washington been a reckless or ambitious commander, he might have made a fatal blunder. It was his continued employment of caution and deception that proved to be among his greatest acts of leadership as the American commander in chief.

The phantom that had lingered since January in the blue hills of northern New Jersey proved to be too elusive for the best army in the world to destroy. Gen. George Washington evaded the cold humiliation of surrendering to the British once again. The specter of defeat may have weighed heavy on the Americans, but the irregulars of Washington’s army remained intact and were ready to fight the British once more. By the end of June 1777, the fox had himself poised for a new campaign. The smooth hills of southeastern Pennsylvania became the temporary homes of the Continental army. Howe and the British knew theirdevil of a fellow would be waiting. And in their sneering reverence, the British had born another legend of George Washington. To them, Washington remained an elusive phantom, or perhaps better stated by a citizen of New Jersey: this true story of America’s indispensable man is that of a real life, Jersey devil.

[1]Washington rode two horses during the war: Blueskin and Nelson. As he did not acquire Nelson until 1778, Blueskin (usually colored a whitish hue in portraits) is most likely the horse Washington rode during the late 1776 and early months of 1777. Mary V. Thompson, “Nelson,” Mount Vernon Digital Library.www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/nelson-horse/, accessed February 2, 2018.

[2]Mark Puls, Henry Knox: Visionary General of the American Revolution(New York: Palgrave

Macmillan, St. Martin’s Press, LLC. 2008), 52. British Gen. William Howe refused to recognize Washington’s command as legitimate. Howe addressed a letter to Mr. George Washington, Esq. rather than General. American Col. Joseph Reed famously refuted the sealed letter by stating, “We have no person in our army with that address.” Henry Knox would write of the encounter to his wife Lucy, July 15, 1776.

[3]New Brunswick, New Jersey was still commonly referred to as Brunswick in 1777 by both sides; therefore, it is referenced here as such.

[4]“The Severity of the Season has made our Troops, especially the Militia, extremely impatient, and has reduced the number very considerably. Every day more or less leave us. Their complaints and the great fatigues they had undergone, induced me to come to this place, as the best calculated of any in this quarter, to accommodate and refresh them.” Washington to John Hancock, January 7, 1777. The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 8, Founders Online, National Archives,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0008, accessed February 20, 2017.

[5]“The chance of war is uncertain; and, in spite of opposition, Philadelphia may fall into the hands of the enemy; but let us endeavour, in case of an accident of that kind, to leave them nothing but the bare walls.” Washington to the Continental Congress on April 12, 1777. The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 9, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives/gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0127, accessed February 20, 2017.

[6]The capitalization of middle brook here is to acknowledge the first of two encampments that took place in the Watchung Mountains as well as to the actual body of water they are named after

[7]“The few deserters who arrive now, all have French rifles. This confirms earlier speculations that the French have again sent large quantities of cannon, rifle, and clothing to the rebels.” June 8, 1777. Friedrich Muenchhausen, At General Howe’s Side, 1776-1778: The Diary of General William Howe’s Aide-de-Camp(Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 14.

[8]John P.Spears, Anthony Wayne(New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1903), 61-62.

[9]John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 210. Continental Army estimates at 12,200 soldiers.

[10]“We have the most respectable body of Continental troops that America ever had, no going home tomorrow to suck – hardy, brave fellows, who are as willing to go to heaven by the way of a bayonet or sword as another mode.” Knox to his wife Lucy, June 21, 1777, in Puls, Henry Knox, 92.

[11]“The spirited manner in which the Militia of this State turnd out upon the late Maneuvre of the Enemy has, in my opinion, given a greater shock to the Enemy than any Event which has happened in the course of this dispute…” Washington to Joseph Reed, June 23, 1777, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 10, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0114, accessed February 22, 2017.

[12]Henry EmersonWildes, Anthony Wayne: Troubleshooter of the American Revolution(New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1941), 106.

[13]David B. Mattern, Benjamin Lincoln and the American Revolution(Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1998), 39.

[14]“A detachment of 700 men was sent to Brunswick to get provisions. Washington is a devil of a fellow, he is back again, right in his old position, in the high fortified hills. By retreating he supposedly intended to lure us into the hills and beat us there.” June 15, 1777, Muenchhausen,At General Howe’s Side, 16.

[15]The towns of Perth Amboy and South Amboy were commonly referred to as “the Amboys,” with Perth Amboy using the stand alone name most frequently.

[16]Charles Willson Peale, The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale & His Family: Volume 1 Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1735-1791(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 237. Peale was an eyewitness to the events that transpired during the first Middle Brook Campaign. Though becoming a soldier, he kept his talents for artistry close at hand and sketched a less memorable drawing of himself along with Washington lounging over the bluffs above the Raritan River. This likely never happened, but it is mentioned here to show Peale’s admiration for Washington as commander-in-chief. The simple sketch portrays Washington as a regular person; someone who is worthy of befriending and of the public’s trust.

[17]“Try to get one or more persons upon Staten Island to give information of any Number of the Enemy that might come over…” Washington to Stirling, June 23, 1777. The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 10, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0115, accessed February 22, 2017.

[18]Peale, The Selected Papers of Peale, Vol. 1, 236.

[19]“The Corps of Rangers newly formed and under your Command…” Washington to Daniel Morgan, June 13, 1777, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 10,Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives/gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0026, accessed February 21, 2017.

[20]British Gen. Charles Cornwallis famously said on January 2, 1777, while viewing the Continental army just to the south of Trenton, that, “We may easily bag the fox in the morning.” Washington would stealthy evade him and attack Princeton the following morning. Richard Ketchum, The Winter Soldiers: The Battles of Trenton and Princeton(Doubleday Publications, 1973), 291.

[21]Bob Ruppert, “The First Fight of Ferguson’s Rifle,” Journal of the American Revolution, November 2014, allthingsliberty.com/2014/11/fergusons-rifle-first-fight/.

[22]Muenchhausen, At General Howe’s Side, 19, entry of June 26, 1777.

[23]The Enemy have plundered all before em & it is said burnt some houses.” Washington to John Hancock, June 28, 1777, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Volume 10, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives/gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0138, accessed on February 22, 2017.

[24]Jason R. Wickersty, “A Shocking Havoc: The Plundering of Westfield, New Jersey, June 26, 1777,” Journal of the American Revolution, July 2015, allthingsliberty.com/2015/07/a-shocking-havoc-the-plundering-of-westfield-new-jersey-june-26-1777/, accessed February 25, 2017.

[25]Muenchhausen, At General Howe’s Side, 17.

[26]Richard Ketchum, Saratoga: Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War(New York: Henry & Holt Company, LLC, 1997), 59.

[27]Numerous correspondences written by Washington through the spring months indicate the very real exhaustion he suffered as he faced desertions and the unreliability of the militias. Much less discussed today, this was also the time when Washington’s natural chestnut hair color began fading to grey, likely from the stress he endured.

[28]Ferling, Almost a Miracle, 205. Estimates indicate that the Continental Army was reduced to about 800 soldiers by the end of January 1777.

[29]Historians have been critical of the British strategy for fighting the war. The fatal flaw by Lord North’s ministry was expecting two different strategies to complement each other rather than undermine one another. The British Parliament’s plan to extend olive branches to would-be Loyalist Americans meant the British were attempting to engage simultaneously in diplomatic persuasion while expecting to prevail in a conventional war. British generals William Howe and later Henry Clinton struggled to adapt to a war entirely different than what the British had been used to fighting in the eighteenth century. They were unprepared to fight a hostile insurgency. For his role, Howe had been chosen because he was a respected military general, but more so because his family name had been well-liked in British America. He showed a willingness to forgive Americans who pledged allegiance back to the Crown. Howe’s lack of urgency to go on the offensive against Washington cost the British several chances to likely crush the smaller Continental forces. Had the British objective been more aggressive from the outset by focusing on completely destroying the Continental army first, and then turn to controlling key cities and ports, the war would have been much different, and likely disastrous for American Independence.

2 Comments

At the Battle of the Short Hills, it was not Lord Stirling’s horse that was shot. It was actually Col Elias Dayton’s horse according to an letter extract by General Maxwell. Col. Shreve (2nd NJ) wrote that Maxwell had to take over the command of the 3rd Pa Brigade when General Conway acknowledged he was unfamiliar with the territory. Dayton, as senior officer in the New Jersey Brigade, took over for Maxwell. Dayton’s advance helped save the rearguard of the 3rd Pa Brigade before the Jersey Brigade fell back to another position and further delayed the British for near 2 hours.

George,

Thanks for reading and for providing this bit of information. If memory serves me correct, much of the descriptions I used for the running engagement came from Friedrich Muenchhausen’s “At General Howe’s Side, 1776-1778: The Diary of General William Howe’s Aide-de-Camp.” One can certainly question the accuracy of either side’s ‘official’ reporting, but I think you’ve done a nice job here.

Cheers.