The name Valley Forge evokes strong emotions and memories that are indelibly embedded on the collective American psyche with legendary stories of immense misery, starvation and suffering amidst great heroic patriotism and dedication. The hilly site outside of British-held Philadelphia served as the winter cantonment—one of seven such large-scale military facilities during the American Revolution—for Gen. George Washington’s Continental army. When historians are asked about this location their almost immediate comment is that there were no military engagements on the site despite the appearance today of cannon and fortifications dispersed throughout the nearly 3,500 acre Valley Forge National Historical Park. Many visitors to Valley Forge are confused by these appearances and automatically assume there must have been some sort of battle; technically, they are correct with their conjecture.[1]

Following the September 11, 1777 Battle of Brandywine, the American and British forces maneuvered as if in a chess match through the southeastern Pennsylvania region. On Valley Creek, only three miles from British Gen. Sir William Howe’s headquarters, was stored a wealth of much-needed American military supplies at the location known as Valley Forge, named for an ironworks established in 1742.

In early 1777, the Continental Congress ordered the creation of a magazine, or military storehouse, at Valley Forge. At this time, Valley Forge was owned by ironmaster Williams Dewees, Jr., the son of the Philadelphia County sheriff and himself a colonel in the Pennsylvania militia. Dewees was not pleased about having such a vital military installation near his forge as he feared the entire area, which also boasted a nearby sawmill and gristmill, would become a target for Loyalist sabotage or British assault during an expected invasion. Despite his objections, the magazine was created and a sergeant’s guard of militia was subsequently requested for its protection.[2]

This military facility along the Schuylkill River was substantial as both the Continental commissary department and the quartermaster general stored materials during the summer of 1777. The majority of the supplies consisted of grain and flour—estimated at 4,000 barrels (one barrel of flour is equivalent to 196 pounds)—besides considerable amounts of military iron equipment including hundreds of axes, tomahawks, shovels, and camp kettles. As the British army began to consolidate throughout the region, Washington’s forces scrambled to remove all of their military supplies from the Greater Delaware Valley to relative safety in places such as the upcountry of Chester, Philadelphia, and Berks Counties. Regretfully, there was no one to remove these valuable supplies; with the bureaucratic confusion of the various military jurisdictions, the fact that all of the workers had been summoned for militia duty, and the overall disruption caused by the movements of the British forces, little thought had been given to this important matter.[3]

On the 17th of September, a fierce storm of pouring rain led to the peaceful “Battle of the Clouds,” and local flooding rendered roads virtually impassable; a military engagement was permanently postponed. American Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene commented that the “violent Storm of Rain which continued all the day and the following night prevented all further operations.” As a further result of the nor’easter, so much ammunition (an estimated 400,000 cartridges) was ruined, primarily due to poorly manufactured cartouche boxes, that Brig. Gen. Henry Knox wrote to his wife, “That this was a most terrible stroke to us.” The British echoed the American remarks. Hessian Maj. Carl Leopold von Baurmeister wrote to Major General von Jungkenn in Hesse-Cassell, “I wish I could give you a description of the downpour. It came down so hard that in a few moments we were drenched and sank into the mud up to our calves.”[4] Washington’s forces strategically withdrew to nearby Yellow Spring, and the odds of removing the mountain of supplies shrank by each drenching hour.[5]

On the evening of September 16, the Continental Army’s forage master general, Col. Clement Biddle, dispatched a letter from Valley Forge to Washington, along with Dewees’s inventory estimate:

I have stopd … to examine the state of the Stores at this place & I enclose to your Excellency an Estimate hastily taken from the Gentleman in Charge which he says may be incorrect—I have desired him to procure Boats & Teams to hawl them to the landing (not 400 yards from the Stores) & as he complains that his hands have all been taken from him who did this Business I have taken the Liberty to assure him that any persons employd in that Service should be exempted from Militia Duty while engaged therein.[6]

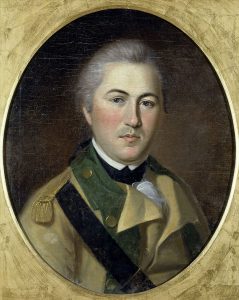

To attempt to rectify this situation, two individuals, who would become immortalized by the American War for Independence, were given the overwhelming assignment of rescuing the military supplies or destroying them to prevent capture. One was Washington’s aide-de-camp Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton, the other a member of one of Virginia’s leading families, Capt. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, who had already attained a reputation as a man gifted in successfully performing perilous and challenging assignments. Although Washington contacted Continental Gen. William Maxwell to support this effort, it became apparent that Hamilton and Lee were alone and needed to rely on their own skill and abilities. Lee would have at his command only eight dragoons while Hamilton would be supported by the same number of Pennsylvania militia under Colonel Dewees. These numbers were hardly sufficient to complete their assignment with much larger British forces so close at hand.

The British commander-in-chief was also aware of the important military commodities deposited at Valley Forge. A British spy, conceivably a Loyalist, had observed the activities at the ordnance repository and reported that the stores included “3800 Barrells of Flour, Soap and Candles, 25 Barrells of Horse shoes, several thousand tomahawks and kettles, and Intrenching Tools and 20 Hogshead of Resin.”[7] At British headquarters, located a mere four miles from Valley Forge, Capt. Friedrich von Münchhausen noted during the evening of September 18 that the problem of the American supply depot was already decided and an action was ordered. A British force consisting two mounted troops from the 16th Light Dragoons and 200 dismounted dragoons, commanded by Lt. Col. William Harcourt, was ordered to Valley Forge to seize “a deserted magazine there.” In addition, three companies of light infantry under the leadership of Maj, Peter Craig of the 57th Regiment of Foot, were dispatched to accompany the dragoons.[8] It was a race against time for both sides.

During the afternoon of the 18th, Hamilton and Lee arrived on the scene along the Schuylkill River. On the crest of the hill known as Mount Joy, which overlooked the area’s mills and the magazine, Lee posted two vedettes (mounted sentries) to provide a warning should the British approach. The remaining dragoons descended to the river with their commander. Lee wrote that “Hamilton took possession of a flat-bottomed boat for the purpose of transporting himself and his comrades across the river should the sudden approach of the enemy render such a retreat necessary.” Later, Hamilton would refer to two vessels of this barge-like configuration that were of a size that could “convey fifty men.” Although the original orders were to try and save the military stores, it became apparent that “their destruction was deemed necessary.”[9]

The British column carefully advanced on the summit of the hill above the creek and the river when they discovered the military magazine and forge was not deserted as their intelligence had reported. Lee reported that, “The fire of the vedettes announced the enemy’s appearance.” Their shots were directed at the van of the British troops as they first ventured into view. John Hamilton, Alexander’s son, later described the quickly-developing melee: “The enemy’s horse came clattering down the hill” in close pursuit of the American horsemen. With their vastly superior numbers, they turned their fury on the small patriot force.[10]

The initial sound of gunfire from the American vedettes saved the day for the remainder of Hamilton’s and Lee’s commands. Lee reported that his “dragoons were ordered instantly to embark” on the flat-bottomed barge. “Of the small party four with the lieutenant–colonel jumped into the boat, the van of the enemy’s horse in full view pressing down the hill in pursuit of the two vedettes” Lee, with the remaining two dragoons, “took the decision to regain the bridge, rather than detain the boat.”[11]

“Hamilton was committed” to the flooded river, swollen by the recent heavy rains, and struggled against the Schuylkill’s “violent current.” Lee placed his safety “on the speed and soundness of his horse.” The two vendettes “preceded Lee as he reached the bridge; and himself with the two dragoons safely passed it, although the enemy emptied their carbines and pistols at the distance of ten or twelve paces.” As Lee and his horsemen escaped westward, the British promptly halted their chase. Lee’s surprise dash for the bridges slightly postponed the British assault on Hamilton’s vessel and afforded him an improved opportunity for escape; however, this respite was only momentary.[12]

Now that Lee was safely out of range the British turned their full fury on Hamilton’s small command on one of the barges; fierce gunfire was dutifully returned. Lee could hear “volleys of carbines discharged upon the boat which were returned by guns singly and occasionally.” The Schuylkill’s strong current halted any chance now of a quick escape, thus making Hamilton and the barge’s crew sitting ducks for the line of British dragoons along the riverbank. Hamilton was only able to escape the repeated volleys by diving from the barge and swimming under water. He stayed under the river’s surface so long that his fellow soldiers believed he had drowned. But Hamilton had acquired exceptional swimming skills as a youth in the Caribbean and safely swam to the river’s opposite shore.

At Washington’s behest, Hamilton later reported to Continental Congress president John Hancock that, “I just crossed the valley-ford, in doing which a party of the enemy came down & fired upon us in the boat by which means I lost my horse. One man was killed and another wounded.” The British suffered no casualties except Major Craig’s horse, killed in the gunfire. Hamilton’s correspondence convinced Hancock of the seriousness of the British closeness to the American capital. His letter included a clear warning that, “If Congress have not yet left Philadelphia they ought to do it immediately without fail, for the enemy have the means of throwing a party this night into the city.” His report included that the boats were “abandon’d & will fall into” enemy hands. Hamilton continued that he had done all he “could to prevent this but to no purpose.” Now with the threat that the British could use these captured barges to quickly “throw a large party” into Philadelphia, the president of Congress recorded that he “removed my papers & now at this place [Trenton] where I should tarry ‘till I hear further.” The majority of the Continental Congress fled the American capital and reformed in Lancaster. As for Valley Forge itself, a local civilian named Sarah Stephens witnessed and recounted years later that, “The place being left to the mercy of the enemy, they set fire to the buildings in which the stores were deposited, the forge and all of the buildings appertaining to it, all of which with their contents were destroyed.”[13]

Consequently, the brief “Battle of Valley Forge” now ended almost as quickly as it began. Although a mere minor encounter of the American Revolution, it was the largest military combat that took place at this site. For the British it was a victory, as they seized vast amounts of the supplies that were not removed or destroyed by Hamilton and Lee. Subsequently, Lee dispatched a messenger to Washington, “describing with feelings of anxiety what had passed, and his sad presage” that Hamilton had fallen in battle. As the commander-in-chief “scarcely perused” the report of the demise of one of his military family, Hamilton stumbled into headquarters, soaked and somewhat worse for wear, but alive. Hamilton echoed the same worries for Lee’s safely. “Washington with joy relieved his fears, by giving his aide-de-camp the captain’s letter.” Lee had also survived the Battle of Valley Forge. “Thus did fortune smile upon these two young soldiers, already united in friendship, which ceased only with life.” Both for Washington and the American Cause the news was good as the loss of these two irreplaceable leaders would have been tragic.[14]

[1] Andrew Zellers-Frederick, “Hallowed Ground: Valley Forge, Pennsylvania,” Military History Vol. 27 (May 2010), 1: 76.

[2] John B. Linn and William H. Egle, eds., “Pennsylvania Archives-Second Series (Harrisburg: Lane S. Hart, 1879), 1: 409.

[3] Clement Biddle to George Washington, September 16, 1777, in Philander D. Chase and Edward Lengel, eds., The Papers of George Washington August-October 1777, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 2: 245.

[4] “Proceedings of a Council of General Officer, 23 September 1777,” Robert K. Showman, and others, The Papers of Nathaniel Greene, 1 January 1777-16 October 1778 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1980), 2: 164. Mark Puls, Henry Knox: Visionary General of the American Revolution (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008), 106. Biddle to Washington, September 16, 1777.

[5] Thomas J. McGuire, Battle of Paoli (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000), 57.

[6]Biddle to Washington, September 16, 1777.

[7] John W. Jackson, Valley Forge: Pinnacle of Courage (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1992), 5.

[8] Maguire, Paoli, 58-59.

[9] Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States (New York: University Publishing Company, 1869) 90-91; Alexander Hamilton to John Hancock, September 18, 1777, in John C. Hamilton, The Life of Alexander Hamilton, 2 vols. (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1840), 1: 85.

[10] Lee, Memoirs, 91. Hamilton, Life, 84.

[11] Lee, Memoirs, 91.

[12] Hamilton to Hancock, September 18, 1777, in Harold C. Syrett and Jacob E. Cooke, eds., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 1768-1778, 28 vols.(New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 1: 326-327.

[13] Ibid, 3 26-328. Hancock to Philemon Dickinson or Alexander McDougall, September 19, 1777,” Paul H. Smith and others, eds., Letters of the Delegates 1774-1789 26 vols. (Washington: Library of Congress, 1981), 8: 3. Henry Woodman, The History of Valley Forge (Oaks, PA: John U. Francis, Sr., 1922) 37.

[14] Lee, Memoirs, 92.

One thought on “The Battle of Valley Forge”

Excellent article, Andrew. I’ve always admired Hamilton and Lee as patriots but I honestly had not known about this incident before. As you mentioned, their loss would have been tragic but may also have affected the outcome of the war, and in Hamilton’s case, the future of the soon-to-be United States.