The ship carrying John Adams was sinking in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean!

The awful thought must have been crippling for Adams, chosen almost unanimously by Congress to travel to France for this second time. It was November 1779 and Adams was being sent as minister to negotiate treaties of commerce, and most importantly – peace with Great Britain, if it should come. Ocean voyages were always dangerous, but a winter crossing was especially so. As the threat of sinking shot through Adams’ mind, he probably regretted bringing his two sons on board with him, twelve-year old John Quincy and nine-year old Charles, even though John Quincy had already accompanied his father on his first trip to Paris the year before. How was Abigail, back in Braintree, Massachusetts going to react when she found out her husband and two sons were drowned at sea?

When a sailing ship of those days ran into trouble on the vast Atlantic Ocean, the captain and crew were totally alone. No SOS distress signal could be sent to nearby vessels; no GPS coordinates could be flashed to friendly coast guard monitoring stations of all nations. The ship just silently sank with all crew and passengers on board. Usually no sign of the vessel or people was ever found.

Just a couple days after having set sail from Boston on November 15, 1779, the doomed French frigate – le Sensible – with the Adams entourage on board, sailed into a “very violent Gale of Wind”[1] and then – the worst nightmare that could be imagined during an eighteenth-century ocean crossing – the vessel sprang a large leak! The captain immediately began to have the icy water pumped out, crew and passengers alike all working the pump frantically twenty-four hours a day. Even young John Quincy took his turn. But the leak got worse, so a second pump had to be installed and used. Even with the group’s best pumping efforts, the leak was getting worse. The ship was sinking! The question was whether the boat would make it to any land before it totally sank into the freezing Atlantic waters. Captain Chevalier De Chavagne decided their only chance would be to try to make it to the first friendly port they could get to. In 1779, that meant Spain, an ally with France against their common enemy – Great Britain.

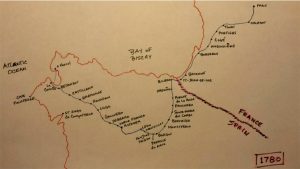

In the morning mist of December 7, 1779, the rocky piece of triangular land called Cape Finisterre was spotted. It was the westernmost tip of Spain and for many centuries considered to be the end of the earth. It meant they had survived the perilous ocean crossing. To make Abigail feel better (but it most likely just increased her anxiety), John Quincy cavalierly later wrote his mother: “One more storm would very probably [have] carried us to the bottom of the sea.”[2] On December 8, the Sensible[3] limped into the Spanish port of El Ferrol which opened to the Atlantic Ocean at the tip of the Bay of Biscay. As soon as the ship docked and the pumping had stopped, the Sensible filled up with seven feet of sea water. John Adams was now stuck on the northwestern tip of Spain, almost 1,000 miles from Paris, not knowing if he should wait for ship repairs (which could take months, if possible at all) or just hoof it from Spain to France. “Whether to travail by Land to Paris, or wait for the Frigate,”[4] Adams mused in his diary. Just the year before, in March 1778 on his first diplomatic mission, Adams had traveled from Bordeaux, France, somewhat near the northeastern Spanish border, into Paris – in 1780 a trip of approximately five days. Adams didn’t know it, but the Spanish countryside was vastly different than the flat, lush, cultivated countryside of France. But John Adams, a type-A personality of his time, couldn’t just sit around. He had to get to work, even if it meant a difficult commute. He just didn’t have any idea of how difficult!

For the week following the port landing, Adams was wined and dined in El Ferrol by Spanish and French officers, chief magistrates and local dignitaries like the French Consul from Coruña. Adams was gracious, but impatient. “Yesterday, I walked about the Town but there is nothing to be seen …”[5] “… very few Horses and those very small and miserably poor; Mules and Asses were numerous but small. There was no Hay in the Country: The Horses, Mules &c. eat Wheat Straw.”[6] One night he was taken, grudgingly, to an Italian opera, “… a dull Entertainment to me.”[7] But Adams’ sweet tooth perked things up a bit for him: “Breakfasted on Spanish Chocolate which answers the Fame it has acquired in the World.”[8]

On the final evening in El Ferrol, Adams was the special dinner guest of the French Consul and his other invitees. In the true combative style of John Adams, the touchy subject of American independence came up. Yipes. Adams wrote that a certain “Mr. Linde an Irish Gentleman a Master of a Mathematical Academy here” was “of Opinion that the Revolution in America was of a bad Example to the Spanish Colonies and dangerous to the Interests of Spain.”[9] Adams always relished a good debate, especially “when I know I am right.”[10] He went on to explain to Mr. Linde how that “opinion” was in error and how Spain should get onboard the independence train to overthrow its own king before it was too late. Then Adams, very wisely apologized, saying he had early morning travel to attend to and must take his leave. Later in his autobiography, Adams reflected,

If, in 1807, We look back for seven and twenty Years, and … had the United States remained subject to Great Britain, Mr. Linde and the Consul and the whole Spanish Nation might be convinced, that they owe much to the American Revolution.[11]

The next morning, Tuesday, December 14, “We arose at five O Clock;”[12] Adams and entourage[13] were sailed around to the southern tip of the bay from El Ferrol to La Coruña. There Adams wrote, they “mounted our Mules. Thirteen of them in Number and two Mulateers … We rode over very bad roads, and very high Mountains” to reach the old, walled city of “Corunna.”[14] But the train of men and mules had barely arrived when John Adams was immediately invited to dine that evening with the “General who is Governor of the Province”[15] in Coruña. The dinner conversation was going great because “The Governor of the Province, told me he had orders from Court to treat all Americans as their best friends.”[16] It was going great … until … “He asked me when this War would finish?”[17] Oh oh. But Adams was diplomatic this time and only gave a very veiled slight to the governor and the Spanish king, replying,

Pas encore [not yet] – But when the Kings of France and Spain would take the Resolution to send 20 or 30 more line of Battle Ships to reinforce the Comte d’Estain and enable him to take all the British Forces and Possessions in America.[18]

All along, Adams had been weighing the decision to either wait for ship repairs in Spain, assuming the Sensible wasn’t to be condemned, or to hit the road by foot. The governor and advisors gave Adams probably the final advice. At least enough so that on December 16, Adams wrote his decision to Samuel Huntington, the president of Congress,

I am advised by every body to go to France by Land. – The Season, the Roads, the Accommodations for travelling are so unfavourable, that it is not expected I can get to Paris in less than thirty days. But if I were to wait for the Frigate it would probably be much longer. I am determined therefore to make the best of my Way by Land.[19]

The next morning the governors of both the province and the town called upon Adams at his “Lodgings at the Hotel du grand Amiral”[20] and invited him to dinner again the following evening. Adams was then given a passport for credentialed free movement within the Spanish provinces, signed by the governor-general of the province of Gallicia, Don Pedro Martin Sermenio.[21]

Once the Adams group arrived in Coruña and the transportation method had been decided, things started to take shape for their overland trek; everything needed for the trip was being collected. Along with Adams’ diplomatic papers were clothes and personal items,[22] food and drink,[23] mules (John Quincy wrote in his diary that one of the mules in their traveling party “had near a Hundred little bells tied round it’s neck”[24]), Spanish guides, and calashes (small, crude two-wheeled carts). And while preparations were being made, the ever-curious John Adams found himself able to take in the local sites – an ancient lighthouse, “two noble Windmills,”[25] convents and churches, and watching a “Souvereign Court of Justice” in session – where Adams noted, “The Robes, Wigs and bands both of the judges and Lawyers are nearly like ours at Boston.”[26]

But before the journey would begin, another official dinner banquet was to be thrown on Sunday, December 19, in which Adams was to be the honored guest. It would be attended by the Spanish attorney general, the chief justice, the “President of the Souvereign Court of the Kingdom of Gallicia”[27] and many other dignitaries. Adams wrote that he was determined to answer any questions the group had “civilly and candidly”[28]… for a change. But it didn’t take long before two Spanish officials started berating Adams about his last name. “I thought these questions very whimsical and ridiculous,”[29] wrote Adams. But the officials kept it up, claiming that Adams must have been born in Spain, as if “this was a peculiar Kind of Spanish Compliment.”[30] Perhaps from the vast amount of wine being consumed that Adams described, it got weird from there. Adams wrote that it was told

… that in several Provinces there were very ancient, rich and noble Families of the Name of Adams and that they were all remarkable for their Attachment to the Letter S. at the End of Adam. They were so punctillious in this that they took it as an Affront to write their Name without this final Letter and would fight any Man that did it.[31]

John Adams made it out of that dinner conversation successfully, but just three days later decided to give a little of a come-back when, “I ventured to ask the Attorney General a few Questions concerning the Inquisition. His answers were guarded and cautious as I expected.”[32]

Adams figured it was time to go. Besides, he was exhausted and wrote he hadn’t slept one single night in the sixteen nights he’d been in Spain. “The Universal Sloth and Lazyness of the Inhabitants suffered not only all their Beds but all their Appartments to be infested with innumerable Swarms of Ennemies of all repose.”[33] He was talking about sharing beds with the constant lice, fleas, and bedbugs. Some nights he thought he’d never live to see France.

Ten days after getting to Coruña, the supplies were gathered and the strange caravan was packed up for their eastward journey. Examining Spanish maps, Adams at first was inclined to want to take the most direct way to Bilbao, the last Spanish town at the French border. It would be a straight line right across the northern coast from Coruña to Bilbao. A guide and an interpreter explained that an almost-impassable mountain range ran across almost the entire length of the Spanish coastline of the Bay of Biscay. What the travelers would have to do, it was explained, was to go southeast from Coruña, and then traverse the straight path that Adams had wanted, through some plains and less-rocky mountains before turning northeast to travel up to Bilbao. In fact, a little history was also passed along to John Adams that day.

The trail recommended by the Spanish guides was, in fact, a famous pilgrimage route that had been traveled for centuries since the middle ages. The road was called El Camino de Santiago (“The Way of Saint James”[34]) and the Adams entourage would be traveling the road, in reverse, of the pilgrims walking the route. Tradition has it that the remains of the apostle St. James are buried in a cathedral shrine in Santiago de Compostella, which ironically is just south of Coruña where John Adams and group began their own pilgrimage eastward. Adams speaks of this pilgrimage road and the story behind it in his autobiography. One of his biggest disappointments, he writes, is that he didn’t visit the cathedral in “St. Iago de Compostella”[35] while he was near it. But now they had to get on their way.

It was Sunday, December 26, 1779 and finally the strange Adams caravan was on its journey to France. “At half after two We mounted our Carriages and Mules and rode four Leagues[36] to Betanzos, the ancient Capital of the Kingdom of Gallicia, and the place where the Archives are still kept.”[37] In the coming days, the travelers would express shock at the squalid conditions that average Spanish citizens lived in and while the trekkers were staying in wayside inns.

The House where We lodge is of Stone … No floor but the ground, and no Carpet but Straw, trodden into mire, by Men, Hogs, Horses, Mules, &c …. On the same floor with the Kitchen was the Stable … There was no Chimney. The Smoke ascended and found no other Passage … The Smoke filled every Part of the Kitchen, Stable, and other [Parts] of the House, as thick as possible so that it was very difficult to see or breath … The Mules, Hogs, fowls, and human Inhabitants live however all together … The floor had never been washed nor swept for an hundred Years – Smoak, soot, Dirt, every where.[38]

But in spite of it all, by reaching the town of Castillano, Adams wrote, “Nevertheless, amidst all these horrors I slept better, than I had done before since my Arrival in Spain.”[39] He doesn’t say why he slept better. Maybe Adams was that tired. Or maybe it was because he knew he finally was on the road to France. Speaking of roads, Adams was equally horrified at those:

The Road was very bad, mountainous and rocky to such a degree as to be very dangerous[40] … The Roads, the worst without Exception that ever were passed[41] … Steep, sharp Pitches, ragged Rocks.[42]

Sometimes Adams rode in one of calashes, but most of the time he rode a mule or (when the terrain ran almost vertically), “sometimes all walk.”[43] The road was so rough, one of the calashes broke an axle, which required that they stop and fix it. As they traveled “The Way” through Spain, Adams formed certain overall lasting impressions:

I see nothing but Signs of Poverty and Misery, among the People. A fertile Country, not half cultivated, People ragged and dirty, and the Houses universally nothing but Mire, Smoke, Fleas and Lice. Nothing appears rich but the Churches, nobody fat, but the Clergy[44] … The Houses are uniformly the same through the whole Country hitherto – common habitations for Men and Beasts – the same smoaky, filthy holes.[45]

But in the easternmost part of Spain, John Adams also beheld a majestic spectacle he had never seen before: the Pyrenees Mountains in winter, “an uninterrupted succession of Mountains of a vast hight,”[46] “white with Snow.”[47] He also found in small villages near Leon townsfolk merrily dancing something called “Fandango” with “a Pair of Clackers in his and her Hand.”[48] Adams and the caravan were drawing up on the noticeably larger city of Leon, situated maybe two-thirds of their way on the trail to Bilbao. “This was one great Plain, and the road through it was very fine,”[49] Adams noted.

The final leg of their journey might be less stressful than the first half, if only John Adams could keep his strong-minded opinions to himself while traveling through a Catholic countryside. But it was not to be. One last affront had to be made. Not intentionally; it was just Adams being Adams.

John Adams had noted while traveling through towns, big and small, that the majority of the inhabitants were dirt poor, with their homes and buildings decaying to dust, except for the numerous beautiful and well-kept churches and cathedrals easily dominating each scene. It struck the Protestant-Congregationalist nerve in Adams that the well-fed followers of the various Catholic religious orders he had noted (mostly “Franciscans” and “Dominicans”) didn’t seem very virtuous. But he kept his feelings to himself … and his diary, of course[50].

But on Thursday, January 6, 1780, while stopped in Leon, Adams was invited by one of their guides to attend High Mass for “The Feast of the King”[51] at the Leon Catholic church. No less than the Bishop would be at the ceremony, so Adams eagerly accepted. “We saw the Procession of the Bishop and of all the Canons, in rich habits of Silk, Velvet, Silver and gold.”[52] But then, to have Adams explain it, as the Bishop turned the corner inside the church and with his hands outstretched, all the people around him “… prostrated themselves on their Knees as he passed. Our Guide told Us We must do the same.”[53] Ha. Protestant Adams was not about to lay prostrate for any religious clergy, so he wrote that he had been content just to bow. Of course, the Bishop spotted John Adams right off – partly by the way he was dressed, and partly because he was the only one standing in the whole church line. “The Eagle Eye of the Bishop did not fail to observe”[54] him, Adams wrote in his autobiography. As the Bishop walked along through the procession, his eyes were squinting solidly on John Adams, as if “I was some travelling Heretick.”[55] But Adams kept his tongue and said nothing, thereby averting a final Spanish scene. Abigail would’ve been proud of him.

The Adams cavalcade arrived in Burgos on Tuesday, January 11, “sneezing and coughing,”[56] having slogged through “fog, rain, and Snow all the Way, very chilly and raw.”[57] Almost all of them were sick with a “violent Cold … all of Us in danger of fevers.”[58] Adams wrote to himself that in the last twenty years of his “great hardships, cold, rain, Snow, heat, fatigue, bad rest, indifferent nourishment, want of Sleep &c. &c. &c.”, he “had never experienced any Thing like this journey.”[59]

The grueling Spanish leg of their journey was almost over. From Burgos, the pilgrims headed almost due north to the coast of the Bay of Biscay, to the seaport town of Bilbao. This point, two months earlier, would’ve been their final destination after a quick shipboard jaunt from El Ferrol or Coruña. But live and learn. Finally, finally, the party reached “St. John De Luz, the first Village in France”[60] on Thursday, January 20, “And never was a Captive escaped from Prison more delighted than I was.”[61] They reached Bayonne three days later. “Here We paid off our Spanish Guide with all his Train of Horses, Calashes, Waggon, Mules, and Servants.”[62] From this point, Adams was back in familiar, friendly country, and from the next French town of Bordeaux and all the way into Paris, Adams would be back on the same path that he’d traipsed just a year before. The Adams procession would all arrive in Paris on February 9, 1780. If the young Adams boys – John Quincy and Charles – thought their school vacation would continue once they all arrived in Paris, they were quickly disappointed. The very next morning of their arrival, their father immediately enrolled them in a Passy boarding school.

John Adams always held that he’d had just three regrets while on this strange pilgrimage through Spain. The first was electing to take the land route at all rather than waiting for a ship. (He would only admit that in a letter to Abigail and never to anyone else). He regretted not seeing the famous terminus point of “The Way,” the cathedral of Santiago de Compostella.

And he regretted that at Bayonne, he had to say goodbye to his mule, “for which I was very sorry, as he was an excellent Animal and had served me very well.”[63] Strangely similar travel companions they were, John Adams and his mule.

[1] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780, sheet 5 of 18 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society, http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/, accessed September 4, 2016.

[2] John Quincy Adams to Abigail Adams, Bilbao January 16, 1780, in Adams Family Correspondence, L. H. Butterfield and Marc Friedlaender, eds., Vol 3; (Cambridge, MA., Belknap Press, 1973), 260.

[3] Adams didn’t think much of their vessel. He wrote in his autobiography, “The Sensible was an old Frigate, and her Planks and timbers were so decayed, that one half the Violence of Winds and Waves which had so nearly wrecked the new and strong Ship the Boston the Year before, would have torn her to pieces.”

[4] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[5.] SUNDAY, page 4; John Adams diary 30, 13 November 1779 – 6 January 1780, Adams Family Papers.

[5] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[13.] MONDAY, page 7.

[6] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[14.] TUESDAY, page 9.

[7] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[9.] THURSDAY, page 6.

[8] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[10.] FRYDAY, page 7.

[9] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[14.] TUESDAY, page 11.

[10] John Adams to Edmund Jenings, September 27, 1782, Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-13-02-0217, accessed September 3, 2016 (Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 13, May–October 1782, ed. Gregg L. Lint, C. James Taylor, Margaret A. Hogan, Jessie May Rodrique, Mary T. Claffey, and Hobson Woodward (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 494–495). The full quotation: “Thanks to God that he gave me stubbornness when I know I am right” begins the fourth chapter in the HBO/Playtone miniseries John Adams, and is producer/writer Kirk Ellis’ favorite Adams quote.

[11] John Adams autobiography, sheet 7 of 18, December 14, 1779, page 2.

[12] John Adams autobiography, ibid, December 15 , 1779, page 3.

[13] Besides Adams himself, there were John Quincy and Charles Adams, Francis Dana (Congressional secretary to Adams’ commission), John Thaxter (Adams’ Congressional private secretary), and two servants.

[14] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[15.] WEDNESDAY, page 13.

[15] John Adams diary, ibid.

[16] John Adams diary, ibid.

[17] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[15.] WEDNESDAY, page 14.

[18] John Adams diary, ibid.

[19] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780, sheet 8 of 18, December 16, 1779; page 1.

[20] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[16.] THURSDAY, page 14.

[21] In 1779-1780, northern Spain was still divided into distinct provinces – Gallicia (northwest), Castille and Leon (northcentral) and Basque country (northeast). Adams would be traveling through all three “kingdoms,” as he called them, and as a diplomatic foreigner would need valid credentials for traveling the provinces. It turned out that it was a good thing Adams had the signed official passport. The party was stopped by military guards at Puente de la Rada, on the road to Bilbao.

[22] “Indeed, We were obliged to carry … our own Beds, Blanketts, Sheets, Pillows” John Adams autobiography, December 28, 1779, page 4.

[23] “Bread and Cheese, Meat, Knives and Forks, Spoons, Apples and Nutts,” ibid.

[24] John Quincy Adams diary 1, 12 November 1779 – 31 December 1779, page 37; December 26, 1779, Massachusetts Historical Society, A Digital Collection http://www.masshist.org/jqadiaries/php/doc?id=jqad01_37

[25] John Adams autobiography, sheet 7 of 18, December 16, 1779, page 4. Fellow traveler John Thaxter had already written of the likeness of the Adams entourage to that of Don Quixote.

[26] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[17.] FRYDAY, page 16.

[27] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 9 of 18, December 19, 1779; page 1.

[28] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[29] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[30] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[31] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 9 of 18, December 19, 1779; pages 1-2.

[32] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 9 of 18, December22, 1779; page 4.

[33] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 9-10 of 18, December 24, 1779; page 4. On January 4, 1780, Adams wrote, “Found clean Beds and no fleas for the first Time in Spain.”

[34] This famous medieval pilgrimage route is still popular and traveled by many hundreds of thousands of walkers each year from Europe and the Middle East. It gained more fame in 2010 with the independent film “The Way” in which Martin Sheen walks the El Camino de Santiago with the ashes of his son, played by Emilio Estevez – who is also the film’s writer, director and producer.

[35] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 10 of 18, December 26, 1779; page 1. Adams describes the story of St. Iago in his autobiography – Tuesday, December 28, 1779, page 4.

[36] A league is somewhere around three miles. The equivalent length has changed over time.

[37] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 10 of 18, December 26, 1779; page 1.

[38] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 10 of 18, December 27, 1779; pages 2-3. John Quincy Adams characterized the common people as, “Lazy, dirty, Nasty and in short I can compare them to nothing but a parcel of hogs.” John Quincy Adams diary, January 3, 1780.

[39] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 10 of 18, December 27, 1779; page 3.

[40] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[26.] SUNDAY, page 25.

[41] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 11 of 18, December 30, 1779; page 1.

[42] John Adams diary, 1780 JANUARY.[1.] SATURDAY, page 34.

[43] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[28.] TUESDAY, page 29.

[44] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 11 of 18, December 30, 1779; page 1.

[45] John Adams diary, 1780 JANUARY.[1.] SATURDAY, page 35.

[46] John Adams diary, 1780 JANUARY.[1.] SATURDAY, page 3.

[47] John Adams diary, 1779 DECEMBER.[31.] FRYDAY, page 33, Adams Family Papers.

[48] John Adams diary, 1780 JANUARY.[6.] THURSDAY, pages 40-41.

[49] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 11 of 18, January 5, 1780; page 4.

[50] Young John Quincy Adams wasn’t quite as reserved as his father. In his dairy, John Quincy gave his own unvarnished observation of the religious domination of the common people, “Poor Creatures they are eat up by their preists. Near three quarters of what they earn goes to the Preists and with the other Quarter they must live as they can. Thus is the whole of this Kingdom deceived and deluded by their Religion. I thank Almighty God that I was born in a Country where any body may get a good living if they Please.” John Quincy Adams diary, January 3, 1780.

[51] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 11 of 18, January 6, 1780; page 4.

[52] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[53] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[54] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[55] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[56] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[57] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 11 of 18, January 11, 1780; page 3.

[58] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 11 of 18, January 11, 1780; page 4.

[59] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[60] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 15 of 18, January 20, 1780; page 3.

[61] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

[62] John Adams autobiography, part 3, “Peace,” 1779-1780 sheet 15 of 18, January 23, 1780; page 3.

[63] John Adams autobiography, ibid.

10 Comments

Enjoyable read, John. Brought back memories as years ago as a college student I travelled (by motor scooter) through a portion of northern Spain and southern France mentioned in the article. Your piece provides a context which, alas, I was completely without at the time of my travels. But having been in Bilbao and crossed the Pyrenees at several points, I can “see” now some of the descriptions by Adams as revealed in your piece. I, too, was stunned by the poverty encountered in several villages, but also by the wonderful, kind-hearted villagers I met. There were times during those travels in the Pyrenees when I know I would have been better served by going by mule!

Jett, thank you for your first-person observations. It struck me as I was reading your words that maybe not much had changed from 1779-1780 and when your trek happened. Have you seen the film “The Way” with Martin Sheen and Emilio Estavez?

John, haven’t seen the film; will make a point to do so. Three of us arrived late afternoon in a foothills village in northern Spain in the early 60s, summer. Adults were in the fields harvesting grain while kids were milling about in the streets. One telephone booth served the town, doors to most dwellings open with chickens and sheep going in and out at their pleasure, straw floors, etc. Not terribly different from when Adams must have seen such villages. We gave kids rides on our motor scooters while parents slowly came back into the town to watch. They warmed up to us, provided some supplies, especially wine, for our journey and sent us off at dusk with flaming torches waving at our departure. Have never forgotten their hospitality!

You’re right! Except for the telephone booths, your description sounded very much like what John Adams & group witnessed some 180+ years earlier. Your description also reads with such warmth, I could tell you treasured your time there. Thank you for sharing your personal experience with myself and readers.

One of my favorites moments of this sojourn is when John Quincy copied some story about nuns into his diary, then had to cross it out thoroughly. What had he heard?

Oh, I can just imagine! John Quincy wasn’t quite as diplomatic in his diary (a practice his father encouraged him to start on this particular adventure – and JQA then kept up the habit until he died) as his father. Being a twelve year old, he was probably inclined to record any lecherous rumor he’d heard about nuns.

Maybe Dad read his son’s diary and made him completely obliterate the text? Neither mentioned what you’re referring to. One wonders….

It looks like John Quincy had to show his diary to his tutor, John Thaxter, and his father, and perhaps even to send a copy home to his mother. So, yeah, his entry on 18 December 1779 was probably a valuable lesson about being discreet until his diary was all his own: http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2009/08/john-quincy-adams-edits-his-diary.html/

Thank you, J. L.!

For readers’ knowledge, John Thaxter was one of the individuals along on the Adams’ Spanish pilgrimmage. Thaxter likened their trek to that of Don Quixote (end note 25).

Yes, great read indeed, thank you. I was not aware that Mr. Adams walked ‘El Camino’, even if it was in the opposite direction. Good for him.

As for his perspectives on the peninsula, they read not much different in his time from today’s visitors to Spain. Regarding the mules, it would probably be the same impression you would get today to see one all tacked-up and ready for an excursion (as in this example, which this town still preserves the practice for tourist eco-trips inland):

http://adamuzturismosostenible.blogspot.com/2011/03/aparejando-un-burro-con-manuel-ruiz-el.html

The only point I wanted to clarify, though, is upon his written impressions about Spain’s contribution to the American War of Independence:

It is interesting that he was travelling through Galicia on December 1779 without knowledge that Spain had already jumped into the fray as an ally on June the same year (after the Treaty of Aranjuez or ‘Family Compact’ between Spain and France was signed in April 1779). Moreover, Spain was already contributing to that war since 1776 in the form of comestibles, monies and weapons aid to the colonists. The only reason it did not readily advertise its aid as the French did went a little further than an impression it did not want to give to its Spanish Colonies in America (which was also true)…

Britain was in control of both Gibraltar and Minorca and could strangle the country’s population with a swift and strong blockade and invasion if it had any reason to suspect any form of antagonism from Spain. On the west, Portugal was also a British ally so it was pretty much the same scenario. It took a lot of evaluation and timing by the Spanish minister to the crown to find the right moment to jump full-fledged into this support (which rendered an important counter-aid to the colonist cause in the Southeast region and helped pay and setup for ‘Le bleu flotte’ of France during the Yorktown siege).

Thank you for your comments about John Adams and his walk through Spain. Actually the word “walk” is symbolic for the story, as Adams and entourage did a combination of riding their rent-a-mules, walking (when the roads were extra-treacherous), and riding in one of the rickety calashes. No easy trekking no matter which mode was used.

The website reference you added showing how Spanish mules are decorated in traditional garb for the tourist trade is exactly how I envisioned their mules to look. Thank you! John Quincy, in his diary, mentions the Spanish fabric decorations, along with the addition of tiny bells all over at least one mule.

Your point about Spain’s clandestine support of America until its public declaration of war against Britain is well taken, along with whether John Adams, while traveling through Spain, was aware of Spain’s status. The timeline gets muddy, but I’ll try to summarize the events, as well as I understand them, of what was happening and when Adams knew the information.

From your comments, I can tell that you’re very knowledgeable about Spain’s difficult position from 1776 – 1779. Not wanting to come out and openly support a rebellion against Britain (even though very bad feelings still existed by Spain from the Seven Years’ War), Spain (like France) started secretly sending supplies in 1776 to America through its dummy company – Hortalez & Co. They used shipping ports in France, Cuba and Louisiana, and even in fact – Bilbao, the Spanish destination point of the Adams group.

John Jay was sent to Spain as a minister in 1779 to encourage more support from Spain. But he found that the Spanish officials in Madrid were in no receptive mood to do that; a big reason for that being that a monarchy wasn’t huge on the idea of promoting independence for a former colony (read: Spain’s own Latin American colonies).

In the meantime, in Feb. 1779, John Adams, got recalled back to America from France – so that Ben Franklin (who Adams didn’t care for) could massage Parisian support in peace. Adams got back to Massachusetts on August 2, 1779 and, feeling like he’d been snubbed by Congress, started working headlong on the Massachusetts Constitution.

You’re right that in spring 1779 while Adams was in France, the Treaty of Arunjuez was signed between Spain and France. It basically, out in the open, declared war against Great Britain. [Technically, Spain was only an ally to France and not to the U.S., but “an enemy to our enemy is our friend”]. Adams may or may not have heard or read about the treaty through letters or newspapers in Paris, before he again set sail for America in summer 1779.

However Adams spent nearly three months back in America (Massachusetts) between August 2 – September 27, 1779 by the time he got word to pack up again and go back to France. He didn’t sail for his new mission (and adventure) until mid-November 1779. So he certainly knew of Spain’s declaration of war against Britain by the time he was klip-klopping with his mule over the Pyrenees. Thank you for adding this chance to show readers the big picture of Adams’ world.