In the summer of 1776, the restored Fort Stanwix (renamed as Fort Schuyler) sat on what was the western edge of civilization in present day Rome, New York. The surrounding area was barely populated, but immediately to the west was unoccupied Indian territory. Therefore, the threat of Indian attack was a serious concern of the troops garrisoning the fort, the 3rd New Jersey Regiment commanded by Col. Elias Dayton. Frequent patrols were required to assess that threat and provide critical information.

On August 7, 1776, one such patrol was sent some seventy miles west to Fort Ontario at Oswego, on the southeastern shore of Lake Ontario. The patrol was commanded by Sgt. Maj. Isiah Younglove, from Capt. Thomas Patterson’s company, and included a Mr. Richard Bell, the guide, and from Capt. Samuel Potter’s company: Sgt. William Aitkin, Pvt. Samuel Freeman, and Pvt. James McGuiness.[1] It seems to have been rather a small group to travel such a great distance into hostile territory, but as they sent out other unspecified patrols, one needs to presume this was normal.

Most of what we know about this patrol comes from an official after-action report from Colonel Dayton that was attached to his letter to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler dated August 15, 1776. The events described below are included in that report. Any additional information is provided by other corroborating sources.

According to that report, nothing material happened until the patrol arrived at Oswego, where they saw a bark canoe and a small hut, about three hundred yards from the fort. An unidentified Indian ran towards the fort and met another near the gate. The patrol waited about a minute when both Indians ran into the fort. The patrol presumed the one who ran from the hut had seen them, and since there were no troops or vessels at Oswego, they presumed the Indians intended to hide themselves. Sergeant Younglove, who commanded the party, determined it best return to the place where they had tarried the night before. It was a good six miles from Oswego, but they needed to rest and clean their muskets, which were not working properly because of the rain.[2]

The location of this place is not specified in the report, but it appears to be some type of high ground near a river. The only place like this, on any period maps, is a large ridge running northeast about ten miles south of Lake Ontario. This is farther from Oswego than the patrol reportedly traveled, so it remains an open question.

The patrol proceeded unmolested, until they were within a half-mile of where they intended to halt. All of a sudden, an estimated ten Mississauga Indians fired upon them. Sergeant Younglove immediately reacted and ordered each man to take cover behind a tree. The patrol quickly obeyed and made ready to engage the Indians, but their guns were so wet that they could not fire them. Sergeant Younglove’s gun burnt the priming in the flash pan about ten times, but failed to fire. The other guns also flashed several times. Only one of the men’s guns went off, but was believed to have caused no damage to the enemy. In short, these guys were in trouble![3]

Contrary to popular opinion, a flintlock musket will fire when it is raining. It is imperative, however, that there is a brisk rate of fire in order to keep things dried out. Black powder is hydroscopic, so if the rate of fire slows down or is stopped all together, the powder fouling that builds up with every shot inside the barrel and around the lock mechanism absorbs moisture and turns into black goo. A light slimy grey film appears on all the metal and things get real slippery. The flint in the jaws of the cock (hammer) does not strike the surface of the frizzen (steel) cleanly, but sort of slides by, so there is no spark and the gun does not fire.

The Indians fired about two rounds in response to the one round gotten off by the Jerseys. Suddenly, Sergeant Aitkin dropped his gun and cried out that he was a dead man. At the same time he was heard to declare, “Do not run boys, but fix your bayonets if they come near you.” With those words, Mr. Bell, the guide, thought he saw Aitkin roll down the bank.[4]

Bell called out to Sergeant Younglove and Private Maginnes, who stood next to the sergeant, to head down the bank. For some reason he wanted to make a stand there. Sergeant Younglove did not answer, but foolishly continued to try and clear his musket’s touch hole in order to fire it. There was nothing in the report as to what McGuiness did, but Bell would wait no longer and went down the bank himself. Freeman, the other private, immediately followed Bell. The two then moved down the bank to where they were out of sight, where they heard two guns fire, after which they heard nothing more.[5]

Short of cleaning their muskets, which they planned to do, Bell’s desire to have them all move down the bank was the correct one. It might have given them more time to do some interim cleaning on the fly. Just picking the touch hole, like Younglove appeared to be doing, was pointless. The gooey fowling inside the barrel would repeatedly clog up the touch hole and prevent the powder in the lock’s flash pan from igniting the powder in the bottom of the barrel. As the regiment’s top sergeant, Younglove should have known better. Believing Younglove and McGuiness were killed, Bell and Freeman immediately made off into the woods about six miles. Freeman had received wounds in both his head and shoulder so travelling must have been somewhat difficult. Nevertheless, they doubled back to the river, where they found the enemy’s tracks still in pursuit of them. So, in order to evade the pursuing Indians, they repeated this process three times and every time they still found fresh Indian footsteps in the mud and grass.[6]

After this exhausting process, the pair left the river and marched about eighteen miles, when they fell in with two friendly Onondaga Indians, who conducted them about twenty more miles. There they met with two other Onondagas, who conducted them still further until they fell in with another scouting party sent out (presumably from Fort Schuyler) to meet them; after which they were all safely conducted to Fort Schuyler, arriving on August 15, 1776.[7]

That same day, Colonel Dayton, stationed at the fort, sent the aforementioned after-action report to General Schuyler about the patrol:

Enclosed I send the Examination of two of the party that I sent on a Scout to Oswego this day sennight. By their account it is probable Serjt. Younglove, Serjeant Aken, and James McGennis all of my Regt. are either killed or taken by the Messagana Indians. The Guide [Bell] says he is sure by their Language they were that Nation. Two of the Onondagas are now with me that brought the two men that escaped from the other side of the Lake.[8]

In truth, it was not as bad as Dayton feared. 2nd Lt. Ebeneezer Elmer, stationed at Fort Dayton, on August 25, recorded some good news in his journal delivered by Pvt. Edward Russell, of his company, who had been sent on an errand to Fort Schuyler:

We are informed by Russell from Fort Schuyler, that the private [McGuiness] left among the Indians with Serjeants Younglove and Aitkins had escaped with a slight wound, running off and hiding till they had all gone off, but after that came near perishing in the woods, being a full week without eating any thing; but through divine assistance was supported and returned safe to his and our great joy. He is not able to determine whether the Serjeants were killed or taken prisoner.[9]

Five days later, Elmer found himself at Fort Schuyler, where he learned from an Indian from Montreal that “Serjeants Younglove and Aitkins were wounded and taken prisoners to Oswego, where a Mohawk Indian, being one of their young warriors, tomahawked their brains out.”[10]

That Indian was incorrect, because on November 17, Capt. Joseph Bloomfield noted that Sergeant Major Younglove, paroled by Maj. Gen. Guy Carleton, the British Governor in Chief of Quebec, returned to the regiment at Fort Ticonderoga, under a flag of truce.[11] According to his company’s account book, Younglove received three months back pay and all expense monies due him.[12] He apparently returned home as a condition of parole or was unable to serve, because another sergeant was appointed sergeant major six days later.[13]

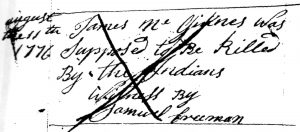

Sergeant Aitkin was not as lucky. The assumption is that Younglove made some kind of a report, as the muster roll of Potter’s company taken at Fort Ticonderoga indicates that Aitkin had been killed on August 11. This roll also indicates that neither Freeman nor McGuiness were wounded. However, since that roll was taken well after the incident, their wounds or injuries were either healed or not significant enough to make note of them.[14] In addition, a crossed-out note in Captain Potter’s company account book under McGuiness’s name states that he was supposedly killed by the Indians on August 11 according to witness Samuel Freeman.[15]

The two sergeants are clearly the heroes of this compelling story of an ill-fated patrol which ultimately lost only one man. Near death, Sergeant Aitkins knew the men of his regiment not only had bayonets, but could use them for something besides a camp kitchen utensil – even against Indians. Furthermore, Sergeant Younglove, at his own peril, continually tried to fire his weapon and protect his little command; giving the rest a chance to get away.

It is also interesting that Younglove was captured in the western Mohawk Valley, but was returned to his regiment up at Fort Ticonderoga, where it had been sent a month earlier. Either British intelligence was superb or their enemy’s movements were not very secret.

[1] Report Attached to Letter from Col. Elias Dayton to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, August 15, 1776, Peter Force, ed., American Archives (Washington, D.C., 1837-53), 5th Series, 1:1034-1035. Regimental Orders appoint Younglove of Patterson’s company as Sergeant Major, April 15, 1776, Ebenezer Elmer, “Journal Kept during an Expedition to Canada in 1776,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, 2(1846):100. Muster roll, November 23, 1776, Capt. Samuel Potter’s company, Col. Elias Dayton’s Battalion of Forces Raised in the State of New Jersey, in Camp at Ticonderoga, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775–1783, National Archives Microfilm Publications, M246, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93, Roll 63, Jacket 54-2.

[2] Report, August 15, 1776.

[3] Ibid. “The Messasaugas (Mississauga) were/are an Algonquian linguistic-stock Indian nation, closely related to the Ojibwa (Chippawa) of Upper Canada (present Ontario), and were dependents/allies of the Six Nations – and the British – in the Revolutionary War. They were indigenous to the Great Lakes (Lakes Erie and Ontario, specifically)….” Glenn F. Williams, personal communication, April 8, 2014.

[4] Report, August 15, 1776. It should be noted here that 2nd Lt. Ebenezer Elmer made a third-hand notation in his personal journal that: “…an express arrived here from Col. Dayton at Fort Schuyler, informing us that…. A ball took Sergeant Aitkins, of Capt. Potter’s company, in the body, upon which he fell, crying out, “I am a dead man, but do not fly, if your guns will not go off, rush them with your bayonets.”” Elmer, “Journal,” 2(1847):179, August 16, 1776. If this express was the same as the official report Colonel Dayton sent General Schuyler, Elmer is clearly exaggerating the event. If not, then the express presented Sergeant Aitkins’s words as far more inspiring than the official report.

[5] Report, August 15, 1776.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Col. Elias Dayton to Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, August 15, 1776, Force, American Archives, 5th Series, 1:1033-1034.

[9] Elmer, “Journal,” 2(1847):187, August 25, 1776. List of company members, May 3, 1776, Mark E. Lender & James K. Martin, editors, Citizen Soldier: The Revolutionary War Journal of Joseph Bloomfleld (Newark, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society, 1982), 40.

[10] Elmer, “Journal,” 2(1847):189, August 30, 1776.

[11] Lender & Martin, Citizen Soldier, 115, November 17, 1776.

[12] 3rd New Jersey Continental Regiment Account Book, 1776-78, Capt. Thomas Patterson’s Company, New Jersey Historical Society, manuscript no. 216. These are undated entries, but other members of the company were paid for the same three-month period on August 31, when Younglove was in captivity.

[13] Elmer, “Journal,” 3(1848):44, November 23, 1776.

[14] Muster roll, November 23, 1776, Capt. Samuel Potter’s company.

[15] 3rd New Jersey Regiment Account Book, 1776, Capt. Samuel Potter’s Company, labeled as “Samuel Potter’s Orderly Book, 1776,” Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Accession No. 966.

10 Comments

My ancestor was Pvt., later Sgt., Ephraim Kibbe (spelled variously as Kibbie or Kibbey). He was in Col. Dayton’s company, but under Col. Dayton”s son, Jonathan Dayton.

Is there any way of finding out if he was involved here. By that I also mean, was he part of the company at that time or did he join it later on.

Thanks,

Perk

I presume you mean Dayton’s regiment, not company. A company was usually commanded by a captain, where a regiment was usually commanded by a colonel. (I say “usually” as there are exceptions, which I do not wish to get into here.)

Elias Dayton commanded the 3rd New Jersey thru ought its existence, so you may need to determine which of the different “establishments” the regiment your source is considering. Even though they had the same commander, the 3rd New Jersey in our story should not be considered the same as the 3rd New Jersey that fought at other locations such as Monmouth Courthouse.

Since his son did not command a company in 1776, I suspect your guy served in the regiment later in the war.

I have not done a detailed study of the enlistemnt rolls of 3rd New Jersey (ca. 1776), let alone the later establishments. (I do hope to do that for 1776 if/when time and/or other projects permits), but will not be pursuing the later years.

You need find out when he served and if he filed a Federal pension application. The National Archives has most of this information (but not everything). Luckily most of this information, including muster rolls, miscellaneous documents, pension information, etc., has been picked up by http://www.fold3.com (the old footnotes.com) that is owned by Ancestry.com. Their information is searchable.

If you were to subscribe to http://www.fold3.com and start searching/browsing through the Revolutioary War records, you might find what you need to know.

Give it a shot. All you need is time and patience. Period handwriting can be a bit tough to handle, but you get used to it.

Perk,

While out on http://www.fold3.com, out of curiosity, I did a quick search for you.

It appears that, in March 1779, Kibbe was listed on a payroll for Capt. Seth Johnson’s company of the 3rd New Jersey. This company was known as “The Colonel’s Company.” This was a designation more common to the British Army, but sometimes used in regiments within the Continental Army.

This explains the confusion on why your records indicate Kibbe was in Colonel Dayton’s company.

There are also several documents indicating this company, prior to 1779, was part of the 4th New Jersey. Since another source I have states Capt. Johnson was transferred from the 4th to the 3rd in July 1778, I suspect all or part of his company came with him, including Kibbe.

My search found no references to Jonathan Dayton. However, Johnson did resign from the army March 30, 1780, so perhaps Dayton took command of his company at that time….

Also, it looks like there is no Federal pension application on file for Kibbe.

Hi Phil,

Thanks for the fast response. I knew I had it in my Legacy Family Tree, the program I use, so I also went to Fold3 and you’re probably right that, about the time of Seth Johnson’s leaving the regiment his son, Jonathan, took over command in early 1780. I hope this will get you there – see “Page 46 – Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783”

Regards,

Perk (:>)

I don’t need to go there, but I will look. Page 46 I get, but what roll and what folder?

Hi Phil,

Below are the urls of what I found that relate to Jonathan Dayton. This must have been the beginning of, while not a frendship, certainly part of a business relationship since Jonathan Dayton was a partner of John Cleves Symmes in his Ohio land purchase and Kibbey was part of it as a purchacer and made at least one trip back to NJ. with mail from Symmes to Dayton. I think that trip was also made to bring Phebe, his wife, back to Ohio.

Note: It appears that in Feb of 1780 Kibbey was promoted to Sergent.

He was discharged on Feb 20th of 1781. So, I guess my question is whether he was ever in the Northern Campaigns (NY, VT, etc.).

Thanks for taking your time,

Perk (:>)

WA State

Ops, I forgot the URLs, see below (:>)

https://www.fold3.com/image/19185594

https://www.fold3.com/image/19185622

https://www.fold3.com/image/19185646

https://www.fold3.com/image/19185661

Discharged Feb 20th, 1781 https://www.fold3.com/image/18833371

I spot checked a few of these. They are showing service record cross-reference cards used by the NARA as finding aids for muster rolls they have on file. Since they do not have a card for Kibbe in early war 3rd NJ (ca. 1776), and they have about a third of their company rolls on file, I seriously doubt he served then. Enlistments in the first two continental army establishments (1775 & 1776) were for a single year or less. By 1777, enlistments were generally for three years or “the war.” Later enlistments were almost always for the duration. So, those inclined to enlist for shorter periods in the beginning, were not likely to serve for longer stretches as the war progressed. What also should be noted is that a lot of unit changes occurring later in the war were the result of unit consolidation due to attrition over the longer enlistment periods. Glad I could be of help.

Thank you Phil,

It’s been a pleasure, I’m looking forward to more articles from you.

P (:>)

This was an interesting story and about a side action from the Revolutionary War. This had special personal interest, as my mom grew up in Rome very close to the site of Fort Stanwix. As a person very interested in this time of our history, stories like this are very much enjoyed!