“Pennies make dollars” is a phrase that has been around a long time and we all know what it means. But, how many pennies does it take to make a dollar? Silly question you may say—it’s one-hundred, of course. That’s the right answer for today’s America, but that would not necessarily be the right answer if you lived in Revolutionary America. The United States dollar as we know it came into existence with the passage of the Coinage Act in 1792 which based the dollar on a decimal system and said that coins would be a certain number of one-hundredths of a dollar—half-dollar equals fifty cents, quarter-dollar equals twenty-five cents, etc. Prior to that, however, the dollar had a different structure.

There is a major point that must be understood in any discussion of Revolutionary War era economics. All parts of the United States today are connected within a single economy. Prior to the completion of independence in the 1800s, however, America consisted of hundreds of individual economies ranging from small villages to large groups of merchants—the latter with close connections to the economies of Europe. Being quite limited in scope, most of these systems operated independently of each other and experienced minimal, if any, influence from the outside world. Each set values and prices had a basis in the local conditions. The coming of war forced the nascent United States to attempt to develop our first true national economy.[1]

In the eighteenth-century western world, the economies of all countries relied to some extent on silver and gold coins (called “specie” or “hard money”) minted by each country. England and the British colonies based their system on pounds, shillings, and pence—one pound (1£) consisted of twenty shillings (20s) and each shilling had twelve pence (12d).[2] A common form of expressing amounts in this system displayed £.s.d and this format will be used in this article.

To our modern decimal-oriented monetary mind this may look to be a complicated system but it does have a distinct advantage. Comprised of 240 pence, a pound can be evenly divided by several numbers—2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16 and so on. Try dividing a dollar of one-hundred cents by 3, 6, 8, 12, 15, 16, etc.—it cannot be done without some fraction left over. In a society without calculators conveniently at hand, having money that could be quickly and evenly divided in many different ways made life a bit simpler.

For most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Americans had a difficult time finding hard money.[3] The economic policies of England prevented the exportation of coins from England and did not allow the colonies to mint their own.[4] In 1781, Alexander Hamilton estimated that just before the Revolution began, specie made up about one-quarter of all the money in the colonies. He calculated that each person held less than 2.0.0 in coin.[5] People also used paper money, barter, wampum, and commodities like corn, wheat, tobacco, or furs that a local economy accepted as legal tender. Because the value of these other forms of money had little consistency to them, colonists took to using coins from other countries including several Spanish and Portuguese coins, the French louis d’or (“French guinea”); the Dutch rijksdallder, German reichsthaler, and Danish rigsdaler (all called the “rixdaller”); and the Dutch leeuwendaalder (the “lion dollar” or “dog dollar”). Unlike today, Americans daily dealt with money truly international in origin.

Of all the possibilities, colonists made the most use of Spanish and Portuguese coins—peso, pistole, moidore, Johannes or Joe, guinea, and doubloon, for example.[6] These coins became common because millions of them had been minted in Mexico and South America where abundant gold and silver existed. Workers refined the silver ore to over ninety percent fineness (the precise percentage set every few years by the Spanish government), rolled it into a rod called a marc and then sliced it into flans which they trimmed to the prescribed weight and stamped with a die and sledgehammer.

Ultimately, the Spanish silver peso de plata became the most frequently used and it circulated under many names.[7] The English called the earliest hand-made peso the “cob” but later terms like “piece of eight,” “Spanish reales,” “eight reales,” and “bit” referred to the coin being made up of eight reales or bits much like the modern dollar consists of four quarters or ten dimes. In 1732, the Spanish started minting pesos on a machine and these became known as the “Spanish milled dollar.” By the time of the Revolution, most people simply called the coin the “dollar.”[8]

Wherever a coin originated, its value rested in the weight of silver it contained. While the value of paper money fluctuated to absurd degrees through periods of inflation and deflation, coins like the silver Spanish dollar retained their value—the precious metal had an intrinsic value that everyone accepted. In England, the price of a troy ounce of silver varied only slightly from 0.5.2 throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[9] In America, however, the value did fluctuate as colonial legislatures set the figure within their own borders. Some believed that setting a high price would attract silver from outside their borders thereby giving their colony a trading advantage. This worked for a short time but prices of goods eventually went up aligning the economies again.

In the seventeenth century, the price placed on silver became a major issue for the colonies. In 1704, Queen Anne attempted to bring uniformity by issuing a proclamation that limited the value of silver coins to a maximum of one-third above the official rate in England known as “sterling.”[10] Parliament added statutory support to the proclamation in 1708 through an act intended to enforce that value throughout the colonies. With the Spanish dollar weighing seventeen pennyweight, nine grains, three mites (a troy ounce equals twenty pennyweight), the proclamation set the value of the coin at 0.4.6 (54d) sterling, a value that would remain in effect well beyond the American Revolution.[11] The money in the colonies that followed that decree came to be known as “Proclamation,” “Lawful,” or “Current Money.”

As might be expected, not all colonies adhered to the proclamation. Clever colonists discovered a loophole in the edict and the subsequent law—both dealt with coins, not silver bullion (bulk silver). The colonies soon began to skirt the law by setting values for silver by the ounce, not for the dollar. In that way, they could effectively set whatever value they desired for the dollar. New England and the south tended to value the dollar at 0.6.0 (72d), the maximum level allowed by the proclamation. In an attempt to stimulate commerce in their region, the middle colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland valued dollars in that region at 0.7.6 (90d), two-thirds above sterling. This became known as “Common” or “Pennsylvania Money.” New York went their own way with a rate at 0.8.0 (96d), seventy-eight percent over sterling, and that money had the name “New York Money” or just “York Money.” No matter where you held your silver, “Ready Money” referred to its value at that colony’s rate.[12]

Confused? It gets more complicated when one considers that much of the above discussion applied to “money of account”—money existing solely on the pages of account books. For example, no English coin existed that equaled one pound (1.0.0) but a coin called a guinea equaling 1.1.0 circulated. Period documents commonly deal in pounds but seldom mention amounts in guineas. Moreover, no matter where one conducted business in the colonies, in day-to-day activity the value of a dollar remained quite stable at 0.6.0.[13]

To add to the muddle, the silver content of a dollar could vary considerably. To begin with, the dollar did not consist of pure silver but, rather, an alloy of between ninety and ninety-five percent silver depending on which governmental valuation had been in effect at the time of the coin’s minting. In 1772, the Spanish set the percentage at slightly over ninety percent but those coins produced as a result of older valuations had greater amounts of silver in them—upwards of five percent more. Whatever the official percentage, a failure to follow the declaration and poor production practices frequently resulted in coins with varying amounts of silver in them.

Other processes—some natural and others unethical—affected the amount of silver in the coins. Just normal use would wear away some of the silver. The practice of cutting coins into pieces to make change resulted in pieces of slightly different sizes even though intended to be equal. The practices of shaving, filing, or clipping the coins removed small—and, hopefully, unnoticeable—shavings of silver which would become a considerable amount over time.[14] A process called “sweating” could chemically take silver out of the coins. Each of these occurrences left a coin with less silver in it and, therefore, not worth as much. For that reason, most people preferred to take a coin by weight rather than by count or “tale.”[15]

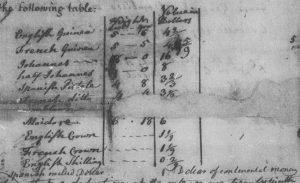

The Continental Congress had the unpleasant task of developing a national monetary system that took into account all the variations that existed throughout the newly united states. Exactly one year after the war of words became a war of weapons at Lexington, Congress formed a committee to “examine and ascertain the values of the several species of gold and silver coins, current in these colonies; and the proportions they ought to bear to Spanish milled dollars.” The report produced by the committee (written almost entirely by George Wythe) placed a value in Spanish milled dollars on each of the different coins commonly circulating in America. The Continental dollar equaled one Spanish dollar.[16]

Although Congress tabled action on the report, they did make use of the values presented in the document.[17] With its beginnings in Philadelphia, the struggling government utilized “Pennsylvania Money” whereby the dollar equaled 0.7.6 (90d). Congress, however, made payments at other rates and typically noted which form the payment came in (“York Money,” for example). The representatives postponed or voted down occasional attempts at standardizing the rate of 0.6.0 per dollar or 0.6.8 per ounce of silver.

Now, let’s add one more bit of potential confusion to your decimal-oriented mind. Anyone reading the above and doing some math to determine how many dollars it took to equal 1.0.0 will have discovered something unusual. With a dollar equal to 0.7.6 (90), it took two-and-two-thirds dollars to equal 1.0.0 (240d). At 0.6.0 (72d), it took three-and-a-third dollars to make 1.0.0. Thirds of a dollar? Indeed, in reading period documents, one often comes across mentions of amounts in thirds, sixths, and even ninths or ninetieths of a dollar. For example, the common American soldier received six and two-thirds dollars per month.

Remember the earlier comments about dividing up a modern dollar? Congress initially used a decimal dollar but soon discovered the challenges of trying to convert amounts in pounds/shillings/pence to dollars and vice-versa. This posed a serious problem. With both systems used so commonly in the American economy, monetary notations often included the amount in both forms but it proved very difficult, if not impossible, to make one equal to the other. In small-scale amounts, the difference would be negligible but, in the large amounts used in business or by Congress, the difference could easily be quite substantial. By summer 1776, Congress had altered its practice and began expressing dollars in the much more convenient ninetieths.[18]

This discussion has concerned itself with one coin—the silver Spanish dollar. The coin proved critical to the colonial and early United States economies and continued to be considered legal tender at the rate of one United States dollar until 1857.[19] Other coins and various forms of paper money and commodities also circulated with their own distinct values and challenges for converting to a common value. Americans not only lived with these challenges, they thrived. So, the next time someone talks of how dull and backward eighteenth-century people must have been, you can tell them how those people had to have rather quick minds to do the necessary monetary calculations in their heads. I cannot imagine many people today succeeding at that.

[1] Richard G. Doty, “Introduction,” Eric P. Newman & Richard G. Doty, eds., Studies on Money in Early America (New York: American Numismatic Society, 1976), 2.

[2] The symbols for the English system come from Roman times—“£” for the pound comes from the Latin “libra,” the basic Roman unit of weight; “s” for shilling comes not from “shilling” but from a Roman coin called “solidus;” and “d” for pence comes from “denarius,” a smaller Roman coin.

[3] John J. McCusker, Money & Exchange in Europe & America: 1600-1775 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 116-7. In part, the colonies themselves brought on the scarcity of specie. Without going into details of period economies, suffice it to say that the colonies conducted a large majority of trade through the use of “bills of exchange,” a process akin to paying with a check today. These bills affected the exchange rate and, at times, it proved more economical to send overseas payment in coin rather than bills. For an in-depth discussion, see McCusker, Money & Exchange in Europe & America: 1600-1775, 3-26.

[4] Some short-lived attempts did take place in the seventeenth century—most notably in Massachusetts.

[5] Hamilton to Robert Morris, April 30, 1781, in E. James Ferguson et al., eds., The Papers of Robert Morris, 1781-1784 (Pittsburg, University of Pittsburg Press: 1973) I:35.

[6] John Mair, Book-keeping Methodised: or, A Methodical Treatise of Merchant-Accompts, According to the Italian Form, 9th ed. (Dublin, 1772), 193.

[7] Alvin Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 152; McCusker, Money & Exchange in Europe & America: 1600-1775, 7.

[8] The term “dollar” originated with the minting of the “Joachimsthaler” in Bohemia starting in 1517. W.G. Sumner, “The Spanish Dollar and the Colonial Shilling,” The American Historical Review, III (1897-1898), 609.

[9] Sumner, “The Spanish Dollar and the Colonial Shilling,” 609. A table of values appears in McCusker, Money & Exchange in Europe & America: 1600-1775, 15-17.

[10] Nobody knows for sure where the term “sterling” originated.

[11] A pennyweight is made up of twenty-four grains and each grain is made up of twenty mites.

[12] For a detailed discussion of colonial rates, see Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America.

[13] Sumner, “The Spanish Dollar,” 616.

[14] These practices diminished considerably with the introduction of milled dollars which had ridges around the edge much like modern dimes and quarters.

[15] Raphael E. Solomon, “Foreign Specie Coins in the American Colonies,” Studies on Money, 28.

[16] “Report of committee regarding bills of credit;” Papers of the Continental Congress (National Archives and Records Administration, M247), roll 33, p.1. Hereafter referred to as “PCC.”

[17] Congress tabled action on the report at least twice. The first time they added Thomas Jefferson to the committee. They tabled it again when the Jefferson-led committee reported a slightly-modified version to the body.

[18] Researchers must be careful. Notations of amounts in decimal appeared exactly as we see today—whole dollars, decimal point, cents. However, on occasion an amount expressed in ninetieths will appear with a decimal point between the whole dollars and the number of ninetieths. It is a rare occurrence but does appear.

[19] Solomon, “Foreign Specie,” 41.

15 Comments

Very informative article, Mike. I have wondered whether the apparent prevalence of a barter economy in the colonies helped to shape the arrangements for organizing and deploying militia during the Revolution (and also the F&I War). I have read that, at least in New England, militia units were organized to follow specific officers, and disputes would arise when “higher authorities” attempted to put officers not of their choosing over them. I have wondered if there were reasons for this apart from mere provincialism. In a barter economy, relationships based upon mutual promises would have developed, naturally, among people who knew each other and who had formed a basis for mutual trust. Militiamen who had carefully bargained for the terms of their service, including pay, which may very well not have been assured to have come in the form of hard money, would likely want leaders who would stand behind those promises and who had the personal economic clout back home to back them up by bartering goods or services of equivalent value. Your thoughts?

Thanks, Ron. Glad you got something out of the piece. I haven’t looked at the militia system enough to be too confident in making generalized statements regarding the topic. As you hint in your comment about New England companies, the militia laws varied some region by region if not colony by colony. In the same manner, I suspect the way officers achieved their rank varied as well. It is my understanding that New England, in particular, elected their officers and, again as far as I know, chose men already prominent in their respective communities. How they became prominent may involve being trustworthy in barter arrangements but I would think their would be more to it including family history.

One other note: my nose crinkled up a bit at your comment on militia bargaining for their terms of service as it is my impression that the militia laws set those terms and left little room for bargaining.

All in all, you bring up an interesting point and maybe somebody else out there with more knowledge of the militia system may be able to provide a more knowledgeable answer than my ramblings.

Thanks for the article, Mike. I have two suggestions. Sweating is a physical process. Coins are placed in a sack and jumbled, abrading the coins and depositing metal in the sack which can then be burned to recover the silver or gold. The origin of the term cob is debated, and wasn’t used by the Spanish, but it does refer to a method of manufacture and not a denomination There are 8 reale cobs, 4 reale cobs etc. There is a good explanation here: https://www.sedwickcoins.com/articles/shipwreck_intro.htm

I don’t know if this had been mentioned before on this site but it wasn’t just economic reference and stability that the Spanish Real provided to the colonies- it also helped secure the victory at Yorktown and thus American independence…

On 15th of August, 1781, a donation in the amount of “500,000 pesos” (about 1.200 livres in gold?) was picked up from the harbor in Havana by the French frigate ‘Aigrette’ which in turn paid for M. De Grasse’s fleet expedition and other soldier needs. This was a direct contribution furnished by Spain during the War of Independence, one of many economic infusions they provided throughout the war.

Spain’s role in the Revolution is another of those areas which needs more publicity. We always hear about France but the Spanish played a significant role as well. Like France, their Catholicism made their decisions about assisting a protestant people rather challenging.

Mike, you are absolutely correct about the limited knowledge regarding Spain’s contribution to the revolution. At the time Spain declared war on 21 June 1779, Louisiana was governed by Colonel Bernado de Galvez. He was ordered to assist the opponents of Great Britain (revolutionaries) and by mid-August, his forces, including local militia, had captured the British fort at Manchac. He then moved North and laid siege to the British fort at Baton Rouge. After enduring 3 days of bombardment, on 21 September, the commander surrendered, not only Baton Rouge fortress, but also the fort at Natchez which was under his command. 20 months later, his army, reinforced with militia units from thruout Louisiana captured Pensacola and Mobile. Many of the Louisiana members of the Sons of the American Revolution proudly trace their ancestry back to those patriot militiamen who were part of the Galvez Expedition.

Mike: Little room for bargaining? I suppose I may have completely missed the boat on this, but I thought bargaining for terms of service, particularly for the militia, was pretty common during the Revolution, although I’m sure it varied a lot depending upon which state we are looking at. My own research revealed a rather naked attempt at bargaining on July 3, 1777, when roughly 900 militia from the “Grants” arrived at Mount Independence and said that their term of service expired in 3 days but that they would stay longer if someone (hint, hint) would agree to pay them. General St. Clair thought this was pretty reprehensible, but it didn’t seem all that different to me from John Paul Jones’ negotiations with his crew, who would hold town meetings to determine what ports they would agree to raid. Maybe these were isolated occurrences?

Well, Ron, setting aside the JPJ situation for the moment and looking at just incident involving the militia from the Grants (which for those unknowing readers refers to the New Hampshire Grants or Vermont) and similar situations, it would appear we are thinking about two different conditions: I’m considering the time when the companies are formed in their respective towns and colonies and their officers are chosen or appointed whereas you are referencing a situation (this one a neat story happening on the Mount) in which the companies are formed, their officers are already serving, and the men are bargaining with a Continental officer under whom they have been assigned to serve at a place away from home. Under the conditions of the latter situation where St. Clair had a dire need for men, the militia certainly had elements in their favor with which to bargain.

As for JPJ’s situation, I would not think of that on the same basis as the above. Be they privateers or part of the Continental or state navies, those crews voluntarily signed onto ships with officers already in a position of command. Militia laws required service in the local company. Further, ships had far more latitude in deciding what waters they cruised. Militia generally went where ordered (the image just came to me of companies of militia roaming at will around the countryside). Lastly, crews received a percentage of the prizes they captured. Militia received a pay rate set by the colonial government. Because of these differences, some ship captains allowed their crews varying degrees of input when deciding where to cruise and/or which ships to attack.

Hope that all makes sense.

The men assigned to Ft Ti had not been paid in a long time or on anything resembling a regular basis. A fair number of them had survived the long Quebec campaign where pay was a huge issue. Those Vermont militia-men were familiar with that problem and were not “bargaining” for the amount being paid, but rather were stating a requirement that if they were to continue on extended service that someone actually had to pay them. This wasn’t just a matter of availability of funds, but also of responsibility – the independent republic of Vermont was newly formed (Jan 1777), had been denied inclusion in the “United States”, lacked cash resources, and had not tasked those men for additional duty beyond their assigned days. For these men their required service as Vermont militia was over. They could not simply “volunteer” and so obligate Vermont to pay for a further period of service. Continental Congress had assigned New York the responsibility for payment, equipping and sustainment of Vermont troops participating in the Continental Army. However, these men were not there under a quota call from Congress, and weren’t volunteering to become Continentals, so New York wasn’t paying them (as Schuyler stated). Therefore, if they were to commit to further employ by the Continental Army, somebody had to be responsible for their compensation. St Clair was as upset by the problem of finding a payment source as he was with the men for demanding that it be determined before they committed. By July 1777, soldiering rates were set for regulars by Congress, and for militia by the individual states; who tended towards the congressional rates, adjusted for the local currency. Variation from those pay scales would have created rate-shopping by potential enlistees. We don’t see that happening, although we do see evidence of bounty jumping; an entirely different problem.

Land commanders held “councils of war” with their subordinate officers to arrive at the best course of action in a situation or the next steps in their campaign. Those subordinate officers represented the interests of their men; a “republican” form of representation vested in appointed or elected officers. Maritime crews, particularly privateers operating under Letters of Marque, led a much more directly participative lifestyle regarding decisions afloat. Seamen joining a crew did so under specific articles identified at the time of signing. Frequently those articles allowed for democratic decision making on certain points of duty. On privateers, since the spoils of war were shared amongst the crew, they had a vested interest in what to attack and when “enough was enough” – terminating a cruise either in foreign port or returning home. Likewise, Captains had a vested interest in maintaining morale and crew commitment. Taking a prize with a dissatisfied crew could lead to the prize, and much of the crew, departing into the sunset.

Perhaps these were poor examples, but I’d agree with Mike that pay scales, especially after declaring independence, were elaborate and fixed by Congress and the States. Early in the war there was variation in militia pay rates across the states, particularly regarding bounties, which could vary by locality depending on quotas, availability of men, and political composition. That variation diminished after the individual colonies began acting under local governance, especially after the Declaration when the states began adopting constitutions and enacting state laws regulating the militia system, including compensation.

I’d think any specific instances of pay-rate negotiation to the contrary would be peculiar; and interestingly noteworthy.

Jim and Mike: Thanks much for those detailed answers! Jim, I particularly appreciate the explanation of reasons for the Vermont militia “debacle”. I should mention that there was an interesting point that came out in the testimony by, I believe, Colonel Hale at St. Clair’s court martial, to the effect that the men were willing to stay but the officers were not. Any theories as to what was going on there?

Mike;

I feel like you did this just for me! You know my passion for, and frustration with, colonial currency exchange! I thank you, sincerely, and appreciate the great references, too!

You are most welcome, Jim. I found McCusker’s and Rabushka’s books to be particularly helpful in understanding colonial money.

A really great and informative piece. I hope you follow up with more on pre-revolutionary and revolutionary American currency.

I suspect understanding the finances of the period are challenging to most folks and I hope my article gives some sort of foundation for a better grasp of the situation. As for follow-up article(s)–just what I need to add to my studies, an attempt to boil down the meat of a topic entire books have been challenged to explain. That being said, we’ll see where my enfeebled mind takes me in the future.

It has been a long time since this article aired but I just came across a document that is worth noting. It’s on pages 15-16 of vol. 7 in the “Amherst Papers” and is dated 1 Nov. 1760. Thomas Barrow, deputy paymaster general, signed the letter but there is no indication of the recipient–likely one or each of the departmental governors in Canada.

“By the Paymaster General’s Instructions to me, I am Ordered to Inform You of the profits & Losses, arising from the Negociation of Money.

“In Obedience to these Orders, I beg leave to represent to You, that a half Johannes, Which in the Province of New York, passes Current for no More, than Seven Dollars & Seven Eights of a Dollar (the rate of Which the Army When it was in the Province has always been paid) appears to me to be worth in Canada Eight Dollars. The Troops at Quebec have always received it at that rate, I Still Continue to receive it so. the Country people Who bring Provisions to the Markett of Montreal And Some of the Most Considerable Merchants, willingly receive it so. by these means, and by the Continual Intercourse between this City and Quebec, the Value of the half Johannes at Eight Dollars, will probably become as General, and as much ascertained here as it is there.—

“Those of Course Who receive the payment of Subsistence, or of Contingencies, in half Johannes, at the rate at which they are Issued in the Province of New York, May have it in their power to gain on each of them Seven pence Sterling.—

“By an Invoice, Sir, of the Money, Which General Amherst has Ordered to be remitted to me from New York, there appears to be in Gold 33016 half Johannes, for Which I have passed my Receipts to Mr. Mortier, at the rate of Seven Dollars, and Seven Eights of a Dollar; if they are Issued by me at the rate of Eight Dollars each, the Publick, will gain by the difference between their Currency in New York, and their Value in Canada Nine Hundred, Sixty two Pounds, Nineteen Shillings and four pence Sterling.—”