There’s a legend that in the Continental Army winter camp of Morristown, Martha Washington, who spent many winters with her husband,[1] had a prowling tomcat nearby that she named “Hamilton.”[2] The myth isn’t true, but it’s not too much off the mark of the real Alexander Hamilton.

But libido aside, if there was ever a Founder who overcame insurmountable odds in his life to propel himself to the top tier of American icons, it was this “bastard brat of a Scotch Pedler.”[3] Born on the obscure Caribbean island of Nevis, his mother was sort of a, uh, “free spirit” who often didn’t bother with the formality of a wedding to hook up with eligible gentlemen. But there was seen a glint of high intelligence in the eyes of young Alexander and he was soon on his way to college in New York. The very bright lad paved his own self-made path through colonial life, starting as an artillery captain in the Revolutionary War. He was noticed by George Washington and was made one of the general’s senior staff aides. Hamilton fought for ratification of the Constitution, and as the first Secretary of the Treasury founded the American financial system.

In 1780, Hamilton, who always had an eye for beautiful women, married Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of Revolutionary War general Phillip Schuyler of Albany, New York. In spite of Hamilton’s almost-always crushing work load, the couple managed to have eight children. Historians have long wondered whether Hamilton had a long-running affair with his sister-in-law, Angelica Church. There was much cooing and dove-eyes made in late night soirees by both Alexander and Angelica to each other, warranting long-time conjecture. But the Treasury secretary did have a very graphic and public affair with another woman, which almost collapsed the financial integrity of the young country.

Here’s how the affair went down:

The summer of 1791 began with Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton worrying about (what would become) the first crash in government securities. Elizabeth (“Eliza”) and their four children left Alexander in the capital city of Philadelphia to spend the summer in Albany at her parents’ house. The threat of summertime epidemics was always a possibility in big cities. One morning, there was a knock at the Hamilton’s South Third Street red brick house. A woman introduced herself as Maria “(probably pronounced ‘Mariah’)”[4] Reynolds. She asked if they could talk in private. Nice guy Alex brought her inside where the twenty-three-year-old Maria started moaning about her husband, James Reynolds,[5] about how mean and abusive he was and that he had even just abandoned her. She purred on and on that if only she could borrow enough money to get back to New York she would be in the safety of friends there. Hamilton, a fellow New Yorker, felt sorry for the beautiful, sultry woman. After all, he wrote, “she had taken the liberty to apply to my humanity for assistance.”[6] Whatever. Thinking that Maria’s predicament was “a very interesting one,”[7] Al said he’d have to bring the money to her South Fourth Street place later that night.

When Hamilton showed up, Maria brought him upstairs to the, uh, bedroom, since I guess it would be rude to accept money at the front door. Rather than suppose what happened, here it is in Hamilton’s own words, “Some conversation ensued from which it was quickly apparent that other than pecuniary [financial] consolation would be acceptable.”[8] Well, okay.

The Hamilton-Reynolds hijinks took off from there and the two met often after that. Guess where? “I had frequent meetings with her, most of them at my own house,”[9] Hamilton recalled. But the fun hit the wall one day when Maria confessed that she and the mysterious Mr. Reynolds had gotten back together and that her husband wanted to meet Hamilton. Yikes. Thinking he might be maybe challenged to a duel or something, Hamilton found James Reynolds instead thankful that Hamilton had protected his wife during this period of turmoil between them. Then Jim Reynolds said he had to leave for business in Virginia, but when he returned, he was wondering if Hamilton could get him a government job when he came back. Hamilton didn’t say anything.

Alexander Hamilton was either too enamored with Mrs. Reynolds or just too naïve to realize he had just been snared into a blackmail trap by two of the sleaziest colonial con artists of the time. But it didn’t end there. Every time Al thought of cutting off the relationship, Maria would write him pleading and rambling letters. Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow said the letters were “notable for atrocious grammar, spelling, and punctuation. Some letters seemed to consist of a single run-on sentence.”[10] But, regardless, Hamilton kept being reeled back in.

By fall 1791, Eliza and the kids returned to Philadelphia and into the Hamilton’s new Market Street house, near Washington’s presidential mansion. Alexander Hamilton, the master day planner, was turning in a major project to Congress, the Report on Manufactures, while still “meeting” with Maria Reynolds. But that’s when it all hit the proverbial fan. Jim Reynolds had returned and indignantly sent Hamilton a letter that he had betrayed him by carrying on with his sweet innocent wife. He demanded compensation for alienating his wife’s affections and thought $1,000[11] ought to about soothe his “wounded honor.”[12]

Hamilton then stopped all contact with Maria Reynolds. That’s when James Reynolds saw dollar signs sprouting wings and flying away, so he turned into a benevolent pimp for his wife. He wrote to Hamilton on January 17, 1792 to ask him to continue to comfort his wife, whom he should consider as a “friend.”[13] When Hamilton thought twice about not continuing to meet Maria, she fired off more grammatically-incorrect letters to the Treasury Secretary. But now in a bizarre twist, James Reynolds claimed that when Mrs. Reynolds had been with Hamilton, she’d been happy and cheerful. But when Hamilton stayed away, she became “Quite to Reverse.”[14] So to make Mr. Reynolds feel better, he asked Hamilton for a “loan” of $30, which he promised to repay. A few days later, he asked for $45, then another demand for $30. Hamilton paid each time until June 1792. Jim Reynolds said he needed $300 for an investment. Hamilton said no. Reynolds said ok, then make that $50. Hamilton said no.

In August 1792, Eliza Hamilton gave birth to their fifth child while James Reynolds wrote to Hamilton and said he needed $200. Hamilton ignored the demand. Soon after that, Reynolds and Jacob Clingman, an accomplice, were arrested by the U.S. government for fraud. They had pretended to be the estate executors for an alleged Revolutionary War veteran. The vet’s name came from a Treasury Department’s list of names, and both Reynolds and Clingman were thrown into jail. But Clingman got his ex-boss involved. It was Pennsylvania Congressman and former House Speaker Frederick Muhlenberg. This story gets thicker and thicker.

Clingman told Muhlenberg that they had proof that Hamilton was the ultimate inside trader. That he was an illegal speculator of government funds and that he’d used James Reynolds as his patsy. Muhlenberg decided to get two other members of Congress in on this: U.S. Representative Abraham B. Venable, and U.S. Senator James Monroe (yes, that eventual-president guy … who also happened to be a close ally of Hamilton’s enemy Thomas Jefferson). Maria met with the three congressmen and produced signed notes by Hamilton, giving proof to the story. (Maria, also staying busy, had found a new “mark” – Pennsylvania governor Thomas Mifflin. She moaned to Mifflin the usual story about her husband’s abuse and threw in that Hamilton had been a great “comforter”[15] to her.)

Just before the congressmen updated President Washington on their findings, they met with Hamilton out of courtesy. Hamilton confessed to the whole thing, surprising the three men. But he said it wasn’t a case of government corruption. It was a case of an extramarital affair and blackmail. Since it didn’t involve illegal federal fraud, the three said they’d keep the story and signed notes quiet. But dummy Hamilton asked for copies of the signed notes. Because copy machines weren’t around yet, Monroe had a Jefferson-ally clerk make a copy for Hamilton … and another one for Monroe. Monroe probably passed the copies and the originals along to Jefferson. But the whole thing then quieted down for a while.

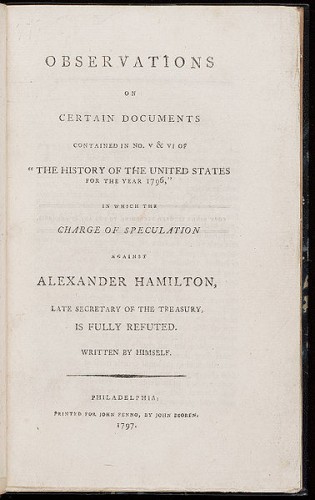

Think that’s the end of the story? Not by far. Five years later, in 1797, someone put the sleazy trash reporter, James Callender, on the scent of Hamilton. No one knows for sure who, but many think it was most likely James Monroe. Monroe may have thought Hamilton was involved with Monroe’s embarrassing recall from France as ambassador. Callender’s expose reported that Hamilton’s admission of infidelity and blackmail was really a cover story to hide the Treasury secretary’s deep involvement in illegal speculation. Callender published the complete story! He logically said Maria’s bad grammar was forged by Hamilton to make it look real. And the final blockbuster allegation: “Hamilton could not have been stupid enough to pay hush money for sex … so the money paid to James Reynolds had to involve illicit speculation.”[16] Hamilton decided to fight back. The prolific writer of most of The Federalist Papers quickly turned out a ninety-five page booklet with a very long title, referred to mostly as “the Reynolds pamphlet.” It’s filled with fact statements, confessions with intimate details, affidavits, and letters. He said his real crime was of love, and that if he was a crook, he would have used a smarter guy than James Reynolds as an assistant.

Think that’s the end of the story? Not by far. The furor mostly died down after the Reynolds pamphlet came out. Washington sent Alexander and Eliza a wine cooler gift with a sincere note of friendship, without any reference to the scandal. But Hamilton wouldn’t let it go. He was convinced Monroe was the one who purposely started all of this by releasing the documents only meant for copying five years earlier. He angrily demanded a meeting with Monroe. Monroe accepted. Both sides brought witnesses to what was beginning to sound like an affair of honor. It nearly was. The tension and anger in the room were almost visible. Monroe finally called Hamilton a “scoundrel” (about the worst name you could call someone), Hamilton fired back, “I will meet you like a gentleman,” which Monroe answered with, “I am ready, get your pistols.”[17]

In one of American history’s greatest ironies, the ever-exploding threats made by Hamilton and Monroe to each other, were mediated and settled peacefully by none other than Aaron Burr (who would go on later to kill Hamilton himself).

By the way, Aaron Burr also was the divorce attorney for Maria Reynolds, who (on the same day her divorce was final), married Jacob Clingman, Jim Reynolds’ old shyster accomplice. Go figure.

[1] Peter Henriques points out that Mount Vernon research historian Mary Thompson “has computed that, in total, Lady Washington (as she was called by the troops) spent 52 – 54 of the roughly 114 months of the war either with her husband in camp, or nearby, in the hopes that they could spend more time together.” Peter R. Henriques. Realistic Visionary: A Portrait of George Washington (Charlottesville, VA., University of Virginia Press, 2006), 91.

[2] This myth that has been in history books for a long time appears to have no basis in fact. It stems from an 1860 two-volume Diary of the American Revolution by Frank Moore. For “Hamilton the tomcat,” it quotes from the diary of “Captain Smythe of the Royal Army” where it reads, “Mrs. Washington has a mottled tom-cat (which she calls in a complimentary way ‘Hamilton’)” and goes on to talk satirically about the thirteen rings around its tale. It was meant as British Army satire of a leading American and nothing more. This fact was uncovered just recently by Boston historian and Journal of the American Revolution associate editor J. L. Bell and published in his blog “Boston 1775”, Febrary 8, 2016; http://boston1775.blogspot.com/ (accessed February 11, 2016).

[3] John Adams to Benjamin Rush, describing Alexander Hamilton, January 25, 1806, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5119 [last update: 2015-12-30]); (accessed February 9, 2016).

[4] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York, The Penguin Press, 2004), 364.

[5] This wasn’t the first time Hamilton had heard the name of Maria’s husband. During an impasse in the 1787 Constitutional Convention, a story arose that delegates were plotting to install King George III’s second son, the duke of York, as an American king. Hamilton traced the source to a letter sent “to one James Reynolds of this city.” Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 237.

[6] The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 21:250, “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” August 1797. The draft of the Reynolds Pamphlet is online at http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-21-02-0138-0001 (accessed February 8, 2016).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid, 251.

[10] Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 366.

[11] Equal to approximately $26,000 in 2015 dollars. http://www.davemanuel.com/inflation-calculator.php. Hamilton had to pay James Reynolds in two installments, December 22, 1791 and January 3, 1792.

[12] The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 21:253, “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” August 1797.

[13] Ibid.

[14] James Reynolds to Alexander Hamilton, March 24, 1792. From The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 11:176.

[15] The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 21:253, “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” August 1797.

[16] Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 530.

[17] The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 21:160, “David Gelston Account of a Meeting Between Alexander Hamilton and James Monroe,” July 11, 1797; Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 539.

2 Comments

In the 17th-19th centuries the English name spelled Maria was almost invariably pronounced Mariah, just as the name Sophia (mother of King George I) was pronounced So-fye-ah. Both pronunciations have died out today.

In the British HORATIO HORNBLOWER miniseries, I was sad to hear Horatio erroneously call his wife Mar-ee-a. However, PRIDE AND PREJUDICE got it right with Maria Lucas.

My family includes generations of Marias from the 1700s to myself.

Thank you for adding more interesting information to the name pronunciations… Maria!