Deciding the guilt or innocence of a defendant in a criminal case today is generally left in the hands of twelve citizens comprising a jury. Prosecutions are left to a member of the district attorney’s office, while the accused has the representation of counsel. The facts in the case are presented, argued, proved, refuted and ultimately weighed. Witnesses are called in support of each side, providing a glimpse of the crime. But what if there is no arrest? No trial? No witnesses? And what if it is 1778, in the midst of the American Revolution?

January 1778 was a time of relative quiet in northeastern New Jersey. The main armies, the British in Philadelphia and Washington’s at Valley Forge, were over a hundred miles away. Bergen County’s residents, living in the shadow of British-occupied New York City and Paulus Hook (modern Jersey City, New Jersey) spent the winter doing tours of duty in the militia, tending to their families, clandestinely trading with the British, or simply going about their normal lives. No actions, small or large, had taken place since the previous autumn and all parties seemed to be content to keep it that way. No Continental troops were stationed in the county, and the garrison of Paulus Hook (the Loyalist regiment of New York Volunteers) stirred little other than to send out small, local patrols. Many Loyalist civilians remained at home, intermixed with their Whig neighbors in uneasy communities across the county’s six townships. Despite political differences, the residents, a unique mix of Dutch, Germans, Danes, Swiss, French Huguenots, Poles, English, Scots, and Irish, along with a sizable black population, shared many ties of culture, religion and family. After a spate of tit-for-tat imprisonments in the first half of 1777 that marked a low point in relations, war against civilians on both sides more or less ended. Indeed, on January 30, 1778, New Jersey’s Council of Safety ordered the last Loyalist prisoners from Bergen County released, either through exchange or parole, upon the British doing the same with the county’s Whigs.[1]

The quiet was finally shattered on January 29, 1778 in a most unusual and violent way. John Richards, a Loyalist resident of New Barbados Township, Bergen County, was in his wagon traveling the road leading from Paulus Hook. It is at this point that the story gets disputed, starting with where the incident actually took place. Loyalist sources, in the form of the newspaper The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, state that Richards was already past the town of Bergen, headed north towards the Three Pigeons Tavern. The tavern was a landmark, located in an area commonly known as Bergen Woods, at a road juncture leading to Secaucus. This was disputed by a New Jersey newspaper, which claimed the event occurred “at Prior’s mill, within sight of the enemy’s centry [at Paulus Hook.]”[2] That would be between Paulus Hook and the town of Bergen, to the southeast, potentially a difference of several miles. What happened next was not disputed in general; the major differences lay in the how and why.

Laying in ambuscade along the road, whichever road it actually was, were Abraham Brower and John Lozier, two members of Maj. John Mauritius Goetschius’ New Jersey State Troops. These troops, authorized by the state for six months service, were raised from amongst the militia in Bergen County and acted as a standing force in lieu of any Continental troops being stationed there. There was no officer with Brower and Lozier, commissioned or otherwise. They may or may not have known Richards personally, but in any case they recognized him as probably coming from the British lines and decided to stop him. Richards, a retired naval captain who had indeed gone within the British lines earlier in the war, upon being stopped produced a pass signed by Lt. Col. George Turnbull, the commander of the New York Volunteers and the post of Paulus Hook. Each side issued passes to residents within their lines, allowing them to visit enemy territory for any number of benign reasons. It was not guaranteed that these passes would be honored by the other side. Richards’ stated purpose for coming within Rebel lines was to visit his family, who then lay ill with smallpox. If his family was at home in New Barbados Township, his journey from Paulus Hook would have been a considerable number of miles and eventually necessitate crossing the Hackensack River, either at a ferry or at New Bridge, the lowest crossing point of the waterway, connecting the modern towns of Teaneck/New Milford to the east and River Edge to the west.

Two American accounts agree that Richards was not alone, but differ in describing his company. The newspaper said that he was with a single, unidentified “Negroe man,”[3] while another account had him in company of his own slave and another slave belonging to an influential resident of Bergen, Cornelius Van Vorst.[4] While no British accounts distinctly mention Richards being accompanied by anyone, clearly someone had to provide them with an account of what happened, and with detail enough to identify Brower and Lozier by name. Whoever informed them, the Loyalists published that Richards “was taken near Bergen by two armed Men, and on the Road between that and the three Pigeons, was shot dead by one of them, as he was preventing the other from robbing him of his Watch” and that “The Names of the Monsters who perpetrated this horrid Tragedy, are Brower and Le Sheair, the former shot him dead.”[5] It should not be surprising that the account published in New Jersey’s newspaper was significantly different: “Upon the road, about six miles from the place where they were taken, Mr. Richard and his negro took hold of Leshier’s musket, (they being in the wagon, and Brower at a little distance on horseback) with design, as Leshier thought, to kill him. Upon this he called to Brower to come to his assistance. As Brower came up, the negro took hold of Leshier, and Richard turned to seize Brower—but Brower, to prevent him, shot him dead on the spot, and the negroes were carried to Maj. Goetschius’s.”[6]

The facts of what actually happened will probably never be definitively known, so it was left to whose side you were on to decide which account to believe. Indeed, the facts were almost irrelevant. Brower and Lozier, as far as Major Goetschius and the State of New Jersey were concerned, had done nothing more than their duty against a violent Tory, and that was all there was to it. The governor of New Jersey, William Livingston, professed to George Washington the previous October that “A Tory is an incorrigible Animal: And nothing but the Extinction of Life, will extinguish his Malevolence against Liberty …”[7] No tears would be shed there on the death of John Richards. The reaction was quite different across the Hudson River in Loyalist New York City.

The outrage amongst the Loyalists was vocal and spirited, particularly since the accounts mentioned that Richards had been on an errand to see his family, They eulogized him: “He was a Man universally known, and as universally beloved; warmly attached to his Friends, humane and candid to his Enemies, benevolent and hospitable to all Men, and has now fallen a Sacrifice to his unsuspecting and generous Temper, for when warned of the Danger of the intended Visit, his Answer was, ‘that his Countrymen, even if they should take him, would never injure him.’”[8] The story took on a life of its own, growing in savagery and callousness. Loyalist Judge Thomas Jones, writing in the years immediately following the war, stated that Richards “Hearing that the small-pox had appeared in his family, he determined to pay them a visit. Upon his way he stopped at a public-house. Here were a number of rebels, to one of whom he was well known. This fellow abused him, called him a tory, a villain, a British scoundrel, and demanded his watch. This Richards refused to deliver, upon which the rebel drew a pistol from his pocket, and with great composure shot Richards through the head. He instantly died. The rebels then took his watch, his money, what things he had with him, stripped the body of its clothes, and deliberately marched off. This horrid, cruel, malicious murder was approved of by Governor Livingston. He recommended the murderer to Congress. Congress rewarded him with a Captain’s commission.”[9] Certainly nothing concerning Livingston, Congress, Brower or Lozier was true in what Jones wrote, and probably little if anything concerning the actual robbery or murder. In a more modern history, Bergen County historian Adrian Leiby, when writing his Revolutionary War in the Hackensack Valley in the early 1960’s, took the Patriot version of events at face value, although more fairly presenting all the participants.[10]

Regardless of the actual circumstances, passion and outrage demanded satisfaction, and if the British in New York City would do nothing to bring the murderers of a Loyalist civilian to justice, then the Loyalists would just have to do it themselves. Four Loyalists in the city, men who would necessarily be familiar with Bergen County and where the two militiamen might resort, at the direction of New York’s mayor David Mathews undertook to capture Brower and Lozier. Two of the Loyalists may have been members of the 4th Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers, a corps recruited principally in Bergen County in late 1776. The other two were civilians, Joseph Hawkins of Bergen Township and Weart Banta of Hackensack Township. The details of what happened next are completely unknown, but by some means on February 5, 1778 the four surprised Abraham Brower and returned safely with him to New York City, where he was promptly committed to the provost, the jail where criminals both military and civilian were held, rather than the Sugar House Prison which confined prisoners of war. All Banta would later say of the episode was “He was sent out on the Express purpose of bringing into the Lines the infamous Brower who had murdered Captain John Richards which he effected.”[11]

The four men, publicly unnamed, were instant heroes: “Upon examining into the Means used by the four intrepid and loyal Persons, who voluntarily undertook to apprehend the aforesaid Brower, and brought him to Town, it was found they had endured inexpressible Anxiety and Fatigue; to reward such brave and fortunate Exertions, a Subscription is opened at Mr. [James] Rivington’s and Mr. [Hugh] Gaine’s for collecting the Contributions of those who have a generous Sensibility of their spirited Enterprize.”[12] Joseph Hawkins, a Loyalist from Weehawken who helped guide Cornwallis’ troops in their 1776 invasion of New Jersey, claimed the reward was a total of fifty guineas, “received each Man a proportionable Share of said Sum agreable to Command.”[13]

It would take nearly two months for Brower to be reunited with John Lozier, but it happened on March 27, 1778 in a manner neither would have wished: “… on Friday, a party of the New-York volunteers, were dispatched towards the English Neighbourhood, in quest of some rebels that were said to be lurking thereabouts, when they seized in the house of one Degroote of that place, four men armed, one of them was Lashier, who was concerned in the murder of Capt. John Richards, whose watch was found in his pocket, and another a serjeant belonging to Capt. [Barent] Roorback, in Gen. De Lancey’s first battalion.”[14]

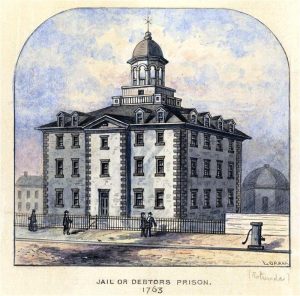

Both Brower and Lozier were lodged in the provost, along with two others captured with the latter, James Van Horn[15] of Major Goetschius’ unit, and Peter Fenton, the deserter from DeLancey’s Brigade, a Provincial unit stationed at the time on Long Island.[16] During the time of the American Revolution, both the British and the United States created prisons to house military captives, but also utilized jails for special cases. The British used the city’s jail, a three-story structure, approximately sixty by seventy-five feet, and called it the provost. It was the old debtor’s prison, built by the City of New York in the late 1750s. For the greatest part of the war, more British soldiers than Rebels were guests at the provost. An examination for July 8, 1778 shows it contained eighteen British and Provincial soldiers (including Peter Fenton), seventeen inhabitants of New York City held on criminal charges, and just four Rebels: two men held as spies, along with Abraham Brower and John Lozier.[17]

Having both men in custody led to an expectation in New York City that they would be brought to justice. With no criminal courts open, New York still being more or less run by the military, a trial would have been by a British military court martial. But no trial brought the two Bergen County men before it. Judge Jones once again vented his frustration in his writings, although his “facts” bore little resemblance to the truth: “General Clinton had never complained of this barbarous and inhuman murder either to Governor Livingston, Washington, or the Congress. He now had the villain in his power. Everybody supposed retaliation would take place. Nothing of the kind. In five days after his imprisonment he had the liberty of the city upon his parole; in about ten he was exchanged as a prisoner of war. Thus the rebels murdered with impunity, and the British Generals were afraid to retaliate. This was the case the whole war. The British Generals were bullied by the rebels, who acted with spirit and resolution. Whenever they threatened their threats were carried into execution. The British were eternally threatening by their proclamations, yet never carried a single threat into execution; though every account daily brought in from the rebel country was giving a list of murders, imprisonments, and robberies committed upon his Majesty’s loyal subjects for refusing to assist, or take up arms, in favour of rebellion.”[18]

While neither Brower nor Lozier were allowed out on parole or exchanged in anything like ten days, Jones was no doubt venting the frustration of many Loyalists about the lack of retaliation upon Rebels while their compatriots swung from a rope. Two incidents in New Jersey alone were probably fresh in their minds. At the end of July, 1777 an Essex County resident named Richard Ennis was tried by a Continental Army court martial for enticing three men of Congress’s Own Regiment to desert to the British, where they would earn three shillings in gold per week and “half a pinte of Rum per Day.”[19] He was found guilty and hanged the next day. Even closer in time to the Richards murder was the fate of two warrant officers for the New Jersey Volunteers, John Mee and William Iliff. The New Jersey Treason Act of 1776 gave the state the power of life and death over those convicted of treason against it, and Governor William Livingston proved quite willing to use it. Mee and Iliff, the two imprisoned recruiting officers, were tried and condemned at Morristown on December 2, 1777, as recalled years later by a militiaman present at the execution: “In the fall … two officers, Captain Iliff & Lieutenant Mee, who had recruited a company for the enemy, were tried at Morristown, condemned & hanged by Sheriff Alexander Carmichael. The [thirty-five] privates of the Co[mpany] were condemned also but were pardoned on condition of enlistment in the American Army.”[20]

News of the imprisonment of Brower and Lozier soon made its way back to Bergen County and their commanding officer, Major Goetschius. Writing to Commissary of Prisoners Elias Boudinot, Goetschius asserted, by the intelligence of an unnamed woman, that the men were in kept in handcuffs, chained to the floor and “only allowed one Biskut a day and a Pint water.”[21] Another prisoner commissary, John Beatty, in December 1778 finally brought the matter to the attention of George Washington himself. His details greatly varied as well, so much so that he stated the murder happened in March, and when Richards refused to desist in resisting, he “at length answered ‘fire and be damned,’ upon which Brower fired and killed him on the spot.”[22]

On December 16, 1778 Washington took the unusual step of writing directly to his counterpart, Sir Henry Clinton, saying Brower and Lozier “are suffering under a confinement of peculiar severity, without any sufficient cause for so injurious a discrimination. I am persuaded I need only call your attention to the situation of these men to induce you to order them relief and to have them placed precisely on the same footing, with other prisoners of war. This will lead to their immediate exchange.”[23] He likewise enclosed Beatty’s report, detailing the alleged abuses taking place in the provost. The British and Continental armies were at this time in the midst of a large prisoner exchange, which prompted Washington to assert the men would be quickly exchanged once they were considered prisoners of war.

It was at this time that Clinton manifested the lack of vengefulness that Judge Jones so lamented. After denying Washington’s claims about conditions in the provost (by means of having the Continental agent in the city, Lewis Pintard, confirm food and clothing had been provided to the prisoners[24]), Clinton put an end to incident, but not before lecturing the Continental Army’s commander on proper procedures:

In order to prevent the irregularities, which under the pretence of Reconnoitring, would otherwise be committed by individuals in every Army, it has been the Custom in Europe (if I recollect right) that any Infantry Patroling without a Non Commissioned Officer should be liable, if taken by the Enemy, to be treated as Spies or Marauders. As Brower & Lozier stood in this predicament when they killed Mr. Richards, I should have been justified in any Severities I had used towards them: I did not, however, consider them as Soldiers, but as belonging to a Banditti, who without Orders or any regular institution subsisted by plundering the peaceable Inhabitants of Bergen County. Regarding them in this light, You will feel that their Crime must have appeared heinous to me; Yet thro’ consideration of the general distraction of the Country, and from the fear that the case might have been misunderstood, I have neither brought them to trial nor have I permitted that they should suffer any particular Severities… To evince to You, Sir, the liberal footing on which I wish all my transactions should stand, as you have avowed Brower & Lozier, I have ordered them to be exchanged immediately.[25]

With the exchange of Brower and Lozier, the affair officially ended. Beatty, in his memorandum to Washington, claimed to have testimony regarding the affair from Major Goetschius and others, but since the militia officer was not an eye-witness to the shooting, his knowledge of it could only have come from the perpetrators themselves. No court of enquiry was held on the part of the state, and no court martial convened on the part of the crown. Indeed, Peter Fenton, the deserter captured along with Lozier, certainly suffered as long as either militia prisoner. The sergeant from DeLancey’s was tried by the British for desertion, found guilty and on May 8, 1778 sentenced to death.[26] The sentence was never carried out, but what became of him is a mystery. On January 1, 1779, after 279 days in the provost, Fenton remained under sentence of death.[27] The battalion of DeLancey’s to which he still belonged was by that point serving in Georgia. He would never rejoin them, and by August 1779 was dropped from the rolls of the provost.

John Lozier would become quickly reacquainted with the provost. On July 23, 1779, Lozier and another militiaman, sixteen year old Cpl. David Ritzema Bogert, were captured near the town of Bergen by a party under Cap. William Van Allen of the Loyalist 4th Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers. The two were described in the New York City press as part of “a gang of rebels, who paint themselves black and commit murders and thefts in Bergen County.”[28] Lozier’s former deed no doubt played a significant role in what happened next, as described later by his companion Bogert: “when taken by Buskirks Regt. he [Bogert] was carried into N. York before Major General Patterson [sic–Pattison] then British Comdt. in N. York & in the Street he was seperated from his companion John Lozier (who was taken with him) he was sent to the Provost kept by Cunningham & deponent to the Sugar house kept by Serjt. Hulton.”[29] There would little leniency shown to Lozier this time. Publicly, it was only stated that “Loshier is safely lodged.”[30] In this case, the term actually meant “In the Dungeon in Duble Irons,” meaning chained in the loathsome basement of the provost.[31]

Brig. Gen. James Pattison was the senior Royal Artillery officer in America and since the summer of 1779 served as commandant of New York City. It was this latter authority that Pattison used in incarcerating Lozier, although what his particular motivation was (beyond the cries of the Loyalists) is unknown. When New Jersey authorities retaliated upon the recently captured Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe of the Queen’s Rangers, an officer very popular amongst the British, Lozier’s situation was relieved. On November 15, 1779, Capt. Stephen Payne Adye, Pattison’s aid-de-camp, wrote to the provost the general’s order:

I am directed by Major Genl. Pattison to signify to you, that notwithstanding the many Crimes laid to the charge of John Lashier, and for which he ordered him to be put in Irons; as he has remained so long in that Situation the General desires that he may be now Released from them, and put upon the same Footing, as the other Prisoners under your Charge.[32]

Lozier’s subsequent exchange at last put an end to the John Richards affair. As compared to the numerous private acts of vengeance that would characterize the war in the South in the latter part of the war, the death of one Loyalist civilian in New Jersey must seem like a minor footnote. To the harried militia of northeastern New Jersey, and frustrated Loyalist refugees in New York City, Richard’s death must have seemed like a microcosm of the war itself. The actual facts of what happened will never be known. Each side was certain its version of events was accurate and correct. The passage of time sometimes sheds new light on historic events, putting the actions of the past into perspective. In the case of the late John Richards, it has not.

*** Todd W. Braisted is the author of Grand Forage 1778: The Battleground Around New York City (Westholme 2016), a book in the Journal of the American Revolution book series. Buy it now on Amazon.

[1] New Jersey, Council of Safety, Minutes of the Council of Safety for the State of New Jersey (Jersey City: Printed by J.H. Lyon, 1872), 203.

[2] The New Jersey Gazette (Burlington), February 11, 1778.

[3] Deposition of John Beatty, Continental commissary general of prisoners, Amboy, December 9, 1778. Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/1607, Great Britain, The National Archives (hereafter cited as TNA).

[4] The New Jersey Gazette (Burlington), February 11, 1778.

[5] The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, February 2, 1778.

[6] The New Jersey Gazette (Burlington), February 11, 1778.

[7] Livingston to Washington, 5 October 1777. George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, 3 September 1777 – 28 October 1777, Library of Congress (hereafter cited as LOC).

[8] The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, February 2, 1778.

[9] Thomas Jones, History of New York During the Revolutionary War (New York: The New-York Historical Society, 1879) 1:280-281.

[10] Adrian Leiby, The Revolutionary War in the Hackensack Valley (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1962), 145-148.

[11] Memorial of Weart Banta to the Commissioners for American Claims, Halifax, 1786. Audit Office, Class 13, Volume 17, folios 34-35, TNA.

[12] The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, February 9, 1778.

[13] Memorial of Joseph Hawkins to the Commissioners for American Claims, no date. Audit Office, Class 13, Volume 96, folio 429, TNA.

[14] The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, March 30, 1778.

[15] Daniel Van Horn, brother of James Van Horn, may have been the fourth man captured, although he does not appear on any prisoner list. Daniel Ryckman, a former acquaintance of the men, recalled many years later “that he [James Van Horn] was taken prisoner while on duty as Express Rider … and carried to the City of New York, where he was confined in the Provost, as the prison was called: that Daniel Van Horn the brother of said James Van Horn was taken prisoner at the same time.” Certificate of Daniel Ryckman, September 29, 1837. Collection M-804, Pension and Bounty Land Application Files, No. R3190, James Van Horn, New Jersey, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter cited as NARA).

[16] “A Return of the Prisoners of War, and the other Prisoners belonging to the United States now in Confinement in the Provost, New York May 11th 1778.” Department of Defense, Military Records, Revolutionary War, Revolutionary Manuscripts Numbered, Document No. 3995, New Jersey State Archives.

[17] “Report of Prisoners Confined in the Provost, New York 8 July 1778.” Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 36, item 38, University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library (hereafter cited as CL).

[18] Jones, History of New York, 281-282.

[19] Court Martial whereof Colonel Thomas Price was president, held at Newark, July 31, 1777. George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, 23 July 1777 — 3 September 1777, LOC.

[20] Pension Application of Israel Aber. Collection M-804, Pension and Bounty Land Application Files, No. S2525, Israel Aber, New Jersey, NARA.

[21] Goetschius to Boudinot, April 28, 1778. Elias Boudinot Papers, Volume 1, Page 132, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[22] Report of John Beatty, Amboy, December 9, 1778. Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/1607, TNA.

[23] Washington to Clinton, Philadelphia, December 16, 1778. Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/1632, TNA.

[24] Pintard to Capt. John Smith, New York, January 1, 1779. Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/1655, TNA.

[25] Clinton to Washington, New York, January 23, 1779. Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/1704, TNA.

[26] General Orders, Headquarters New York, May 8, 1778. Orderly Book of the Three Battalions of DeLancey’s Brigade, Early American Orderly Book Collection, Reel 4, No. 44, New-York Historical Society.

[27] Adjutant General’s Report of the provost, January 1, 1779. Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 50, item 1, CL.

[28] The Royal Gazette (New York,) July 24, 1779.

[29] Pension Application of David Ritzema Bogert, Collection M-804, Pension and Bounty Land Application Files, No. W3502, David R. Bogert, New Jersey, NARA.

[30] The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, July 26, 1779.

[31] Weekly State of the provost, November 1, 1779. Sir Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 75, item 28, CL.

[32] Adye to provost martial, New York, November 15, 1779. Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1875, Official Letters of Major General James Pattison, Commandant of New York, (Printed for the Society: New York, 1876), 300.

5 Comments

Todd,

This is a great, complicated story and you did well in pulling a lot of information together. You touch on the jurisdictional issues of state and military courts and I just wanted to clarify one point when you say that no courts were operating in NY – I am assuming you are referring to the City and not the state.

In the spring of 1777, five and one-half counties of NY’s fourteen were occupied and would have fallen under British martial law to the extent they could enforce it. In the remaining counties the courts were indeed up and running and doing a robust business in the prosecution of those involved in treasonous conduct; the same thing in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts (I can only assume much the same thing in the remaining NE states). Civil cases, such as those involving debt, would have been of less importance and only really became an issue when they came flooding into the courts at the close of the war.

Your story represents the crucial aspects of fluid jurisdiction taking place dependent upon the strength of armies to enforce their prerogative. To the extent they could not, we see the rebel factions assuming that role, filling the vacuum and imposing their own forms of justice.

Hi Gary, yes, the British occupied New York is what I was referring to. The counties of New York State, as opposed to the province, as you point out, had their own judicial system operating, as well as the rest of the United States. In the context I was writing of though, I was referring to the British occupied area.

Thanks, Todd, for this very informative article.

Great article. John Lozier is my direct 8th Great Grandfather. My Grandmother was a Lozier and they still used John, as her brother my Great Uncle was named John. It’s amazing how close not only my existence, but my families came to being erased by what looked like a borderline crime. I’ve read about this before including being astonished that George Washington and Sir Henry Clinton discussed this, I have read the Congressional record online. My family never discussed his acts, we knew he served. We could never figure out why none of the woman could enter the DAR including my sister. I developed a suspicion that his militia status and this incident were at fault. Anyway I hope you get this, thanks for the balanced perspective. Anything else you know about Lozier would be great. Thanks again.

Thank you for this article. I have enjoyed many of your well written and well researched articles. I am working on the paper trail for my Brower line and will keep this Abraham in my files. I’m not certain how he connects to my Adolphus Brower who was killed by lightning in 1742 in Hackensack. Again, thank you.