On April 20, 1775, John Hunter Holt announced to the public his recent acquisition of the Norfolk newspaper, the Virginia Gazette or Norfolk Intellingencer. For a newspaper that had only been in print since 1774, this sudden change in ownership was more than just a business venture, it would serve as an open act of rebellion against Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore. Continuing in his announcement, Holt insinuated that those from whom he purchased the press, William Duncan and Robert Gilmour, had caused “many difficulties with which the business of this press has hitherto been obstructed.”[1] As his father, John Holt, recognized in a letter to Samuel Adams on January 29, 1776, “it was by means of newspapers that we received and spread the notice of the tyrannical designs formed against America and kindled a spirit that has been sufficient to repel them.”[2] It was by means of the newspaper that the seizure of his son’s press by Lord Dunmore was brought about at the end of September 1775.

John Hunter Holt’s father, John Holt, was the patriot printer who published the New York Journal in New York City. The elder Holt had formerly been a resident and mayor of Williamsburg, where he learned the printing business from his brother-in-law, William Hunter, printer of the Virginia Gazette from 1751-61 and 1775-78. Relocating to New England in 1754 due to financial difficulties, John Holt forged a business relationship with James Parker and eventually purchased Parker’s New York paper, the New York Gazette, in 1762, changing the name to the New York Journal.[3] During the Stamp Act crisis, the elder Holt openly opposed British rule by continuing to print his newspapers without the British mandated stamps, stating that “he had no choice; he could not order stamped paper from the crown without certain destruction to his person and property from the general resentment of his countrymen.”[4] As a printer, the elder Holt developed a reputation for being a strong Whig who advocated for the rights of the colonies. Outside of Boston, he became one of the most important printers due to his coverage of the struggle between the colonies and England. His publication of the Journal of Occurrences in 1768 and 1769 allowed news of the struggles in New England against British rule to reach a much wider audience as the journals made their way to the other colonies.[5]

In April 1775, the three newspapers being published from the capitol in Williamsburg and the sole version out of Norfolk all carried the name Virginia Gazette, the Norfolk version adding the subtitle of Norfolk Intelligencer. There was no real difference in the various versions aside from the mottos that adorned the top of each paper as all carried similar news and advertisements. Colonial assemblies, like the Virginia House of Burgesses, utilized the “Gazettes” as part of their official record and mandated that resolutions and proclamations be printed in the “Gazettes” allowed for some sort of government oversight of the press.[6]

The younger Holt no doubt was influenced by his father’s patriot connections and stern stance against Parliamentary rule when he took over the Norfolk Intelligencer in April 1775. Through these connections, the purchase of the Norfolk newspaper by the younger Holt was certainly made possible. As an ardent patriot and son of a patriot printer himself, it is no surprise that John Hunter Holt spoke in tones that echoed his father, both at the beginning of his venture and for the remainder of his time at the press. In his first issue, Holt let it be known that “the subscriber enters upon the office encumbered with the bad effects of those difficulties, which, however, he will make it his study to remove and flatters himself with the prospect of success.”[7] Only thirty when he took over the press, John Hunter Holt had a sneaking suspicion that he would only be in business six months, a suspicion that would prove true.

Two months after taking over the press in Norfolk, Virginia’s colonial government took a drastic turn. Governor Dunmore fled Williamsburg, fearing for his and his family’s safety as the result of his growing dispute with the Williamsburg citizens in regards to the gunpowder incident from the previous April. As was printed in the June 15, 1775 issue of the Norfolk Intellingencer, Dunmore stated that he was “fully persuaded that my person and those of my family likewise, are in constant danger of falling sacrifices to the blind and unmeasurable fury which has so unaccountably seized upon the minds and understanding of great numbers of the people.”[8]

From his new station aboard the HMS Fowey, now removed from Yorktown to the Elizabeth River near Norfolk and reinforced by a detachment of soldiers from Florida, Dunmore began ordering raids of Tidewater plantations for supplies and stores to provide for his small naval force. With these raids came protests from the four regional newspapers, each echoing the other in their challenge against the policies of the British government, and more specifically, the activities of Dunmore and his fleet commanded by Capt. Matthew Squire.

The first report of Dunmore’s tenders seizing Virginia goods was published in Holt’s paper on July 5, 1775. In it, Holt reported that “a brig lately loaded by Gibson, Donaldson and Hamilton of Suffolk with a large quantity of provisions, was lately seized by some of the tenders, and taken to Boston for the supply of the navy and army.” On August 16, Holt called out the commander of the HMS Otter, Captain Squire, stating that “last week several slaves, the property of gentlemen in this town and neighborhood, were discharged from on board the Otter, where it is now shamefully notorious, many of them for weeks past have been concealed and their owners in some instances ill-treated for making application for them.”[9] The squabble with Captain Squire would only increase in its magnitude in the coming weeks.

A week later in the August 23 issue of the Norfolk Intelligencer, Holt published an account of the quartering of British troops by Dunmore in a warehouse owned by Andrew Sprowle. In this report, it was stated that Mr. Sprowle had protested against the quartering of troops in his property but “Lord Dunmore paid no attention to his repeated solicitations, but still continued to keep forcible possession, for the space of ten or twelve days.” Holt continued his attacks against Dunmore and Squire by recommending “to the inhabitants of this county that they have no connections or dealings with Lord Dunmore or Capt. Squires, and the other officers of the Otter sloop of war, as they have evinced on many occasions the most unfriendly disposition to the liberties of this continent, in promoting a defection among the slaves, and concealing some of them for a considerable time on board their vessels.”[10]

The unremitting attacks by Holt against Dunmore and Squire came to a head beginning with the September 9 issue of the Norfolk Intelligencer. A week prior, on September 2, the Tidewater region had been struck by a hurricane that caused great damage throughout the area. On reporting the hurricane, Holt printed, “on Saturday last between 12 and 1pm came on one of the severest gales within the memory of man, and continued with unabated violence for eight hours.”[11]

The hurricane brought great embarrassment towards Squire and his fleet as the Mercury man-of-war went aground in the Elizabeth River. But it was the grounding of Squire’s own ship, the tender Liberty in Back River in Elizabeth City County, that brought forth the fury of Captain Squire upon both the town of Hampton and the press of John Hunter Holt. When the grounding of his vessel occurred, Squire abandoned the ship, only to escape the Hampton citizenry by taking “shelter under the trees . . . and in the morning under disguise to some negro’s cabin, from whom he borrowed a canoe, by which means he got off,” according to Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette of September 7. Further insulting to Squire was Holt’s September 6 issue where he wrote “is it not a melancholy reflection that men, who affect on all occasions to style themselves ‘his majesty’s servant’ should think the service of their sovereign consists in plundering his subjects, and in committing such pitiful acts of rapine as would entitle other people to the character of robbers?” Pinkney, in his Virginia Gazette on September 14, regaled his readers with a rumored story: “Lord Dunmore, it seems, fared but poorly in this hurricane, as, by some accident or other, occasioned by the confusion in which the sailors were, his lordship fell overboard and was severely ducked. But according to the old saying, those who are born to be hanged will never be drowned.” [12]

Sure to be angered by the grounding and subsequent loss of his vessel to the town of Hampton, Squire now had to face personal attacks from the newspapers. In the same issue as the story of Dunmore falling in the water, Pinkney reported that Squire had “taken two or three vessels belonging to gentlemen in either Norfolk or Hampton. What a saucy coward! How miraculous it is, that men-of-war can overcome and be the terror of oyster boats and canoes.” In their September 16 edition of the Virginia Gazette, Dixon and Hunter referred to him as a sheep stealer, but it was the words of Holt that struck a chord.[13]

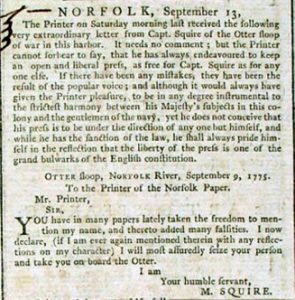

On September 9, as printed in the September 13 issue of the Norfolk Intelligencer, Squire wrote to Holt, “Sir, you have in many papers lately taken the freedom to mention my name, and thereto added many falsities, I now declare, if I am ever again mentioned therein with any reflections on my character I will most assuredly seize your person and take you on board the Otter.” The disrespectful response from Holt must have certainly continued the build-up of anger within Squire: “it needs no comment but the printer cannot forbear to say, that he has always endeavored to keep an open and liberal press, as free for Captain Squire as for anyone else, if there have been any mistakes, they have been the result of the popular voice, and although it would always have given the printer pleasure, to be in any degree instrumental to the strictest harmony between his majesty’s subjects in this colony and the gentlemen of the navy, yet he does not conceive that his press is to be under the direction of any one but himself, and while he has the sanction of the law, he shall always pride himself in the reflection that the liberty of the press is one of the grand bulwarks of the English constitution.”[14]

Adding further to Squire’s anger was his disagreement with the Hampton Town Committee regarding the return of his tender’s materiel. In Pinkney’s September 14 Virginia Gazette, Squire had published his demand to the city of Hampton, composed on September 10, that “the king’s sloop, with all belonging to her be immediately returned, or the people of Hampton who committed the outrage must be answerable for the consequence.” In response, the town committee of Hampton had their rebuttal published in Dixon and Hunter’s September 23 Virginia Gazette, which, like Holt’s response on the 13th, proved to be less than flattering towards Squire’s demands. The town committee accused Squire and his vessels of engaging in “pillaging and pleasuring” rather than “His majesty’s service.” They also demanded the return of a slave named Joseph Harris and other slaves who had been stolen and used against the town in the act of pillaging, the return of all vessels Squire had seized, and that he “shall not, by your own arbitrary authority, undertake to insult, molest interrupt, or detain the persons or property of any one passing to and from this town.” With adherence to these demands, the Hampton town committee agreed to return the tender’s materiel, which they claimed was not stolen, but procured from an abandoned vessel.

Through all the insulting language over the course of the summer, it was the September 20 issue of the Norfolk Intelligencer that forced the hand of Dunmore and Squire to bring an end to the insolent words of Holt. In this second to last issue of his paper Holt published:

we are informed from good authority that a system of justice similar to that adopted against the devoted town of Boston, is likely to be established in this colony, by the renowned Commodore of the Virginia fleet. He has, in the course of this week, as a reprisal for the loss of his tender, seized every vessel belonging to Hampton that came within his reach, and thereby rendered himself the terror of all the small craft and fishing boats in this river; especially the latter, having brought some of them under his stern, by a discharge of his cannon at them. He has likewise seized a vessel belonging to the Eastern Shore, and having honored the passengers so far with his notice, as to receive them on board his own vessel, took the liberty of sending one of their horses to Lord Dunmore. This act of generosity we not doubt will gain him considerable interest with his Lordship, it being an instance of his industry in distressing a people who have of late become so obnoxious to his Excellency for their spirited behavior. We hope that those who have lived under and enjoyed the blessings of the British constitution will not continue tame spectators of such flagrant violations of its most salutary laws in defense of private property. The crimes daily committed by this plunderer we would not willingly brand with the odious name of piracy, but we are confident they come under those offenses to which the English laws have denied the benefit of clergy.[15]

The September 27 issue of the Norfolk Intelligencer, which would be the paper’s last issue, published personal attacks against Dunmore’s family, especially the actions of his father during the Jacobite Rebellion in 1745. Along with the attacks against Dunmore’s family, Holt took one more chance to insult Squire by implying that the British captain had engaged in some form of bestiality by being “too free with people sheep & hoggs” during a recent seizure of a vessel off of Hampton.[16]

The result of this final tirade by Holt against Squire was the seizure of his printing press on September 30. It was reported in Dixon and Hunter’s Gazette on October 7:

Yesterday came ashore about 15 of the King’s soldiers, and marched up to the printing office, out of which they took all the types and part of the press, and carried them on board the new ship Eilbeck, in presence, I suppose, of between two and three hundred spectators, without meeting the least molestation; and upon the drums beating up and down the town, there were only about 35 men to arms. They say they want to print a few papers themselves; that they looked upon the press not to be free, and had a mind to publish something in vindication of their own characters. But as they have only part of the press, and no ink as yet, it is out of their power to do anything in the printing business. They have got neither of the compositors, but I understand there is a printer on board the Otter. Mr. Cumming, the bookbinder, was pressed on board, but is admitted ashore at times. He says Captain Squire was very angry they did not get Mr. Holt, who happened to be in the house the whole time they were searching, but luckily made his escape, notwithstanding the office was guarded all round. Mr. Cumming also informs, that the captain says he will return everything in safe order to the office, after he answers his ends, which, he says will be in about three weeks.[17]

Dunmore defended the action when he wrote to Lord Dartmouth on October 4, “The public prints of this little dirty borough of Norfolk, has for some time past been wholly employed in exciting, in the minds of all ranks of people the spirit of sedition and rebellion by the grossest misrepresentations of facts, both public and private; that they might do no further mischief I sent a small party on shore on Saturday last [Sept 30] at noon and brought off their press type, paper, ink, two of the printers and all the utensils and am now going to have a press for the king on board on of the ships I have lately taken into his majesty’s service.”[18]

Protests abounded from all corners, both against the actions of Dunmore and Squire and against the lack of action from the citizens and militia in Norfolk. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson, John Page wrote that the citizens of Norfolk “are under a dreadful apprehension of having the town burnt . . . many of them deserve to be ruined and hanged but others again have acted dastardly for want of protection.” While in session at the Continental Congress, Richard Henry Lee yearned to hear “the disgraceful conduct” of Norfolk. The Norfolk town council reacted by calling the raid “a gross violation of all that men and freemen can hold dear.” In their letter of protest, published in Purdie’s October 13 Virginia Gazette, they demanded Dunmore to return the seized materials and punish Squire.[19]

Dunmore responded several days later, writing, “if any individual shall behave himself as your printer has done, by aspersing the characters of his majesty’s servants and others, in the most scurrilous, false, and scandalous manner, and by being the instigator of treason and rebellion against his majesty’s crown government, and you do not take such steps as the law directs to restrain such offenders, I do then expect you will not be surprised if the military power interposes to prevent the total dissolution of all decency, order, and good government.”[20]

For his part, Holt promised his readers a return of his press. In Dixon and Hunter’s Virginia Gazette, along with Pinkney’s, he published the following:

The subscriber having been prevented from continuing his business, by a most unjustifiable stretch of arbitrary power, begs leave to inform the public that he has some expectations of procuring a new set of materials, which, if he should be so fortunate to succeed in, will enable him once more to apprize his countrymen of the danger they may be in from the machinations and black designs of their common enemy; the particular place where the office will be erected is not yet fixed, but it will be so near Norfolk as to give him an opportunity of receiving the earliest and most authentic information of the proceedings of the gentleman of the army and navy and of sounding the alarm whenever danger approaches; as his paper has hitherto been free and open to all parties, he intends to observe the same caution and impartiality in his future publications and cannot but flatter himself that his conduct has been such as will entitle him to the future encouragement of his subscribers and the public.

Unlike his father, however, the younger Holt did not reenter the printing business until after the Revolution when he continued the trade in Richmond until his death on May 16, 1787. While his father continued spreading the word of the Revolution in New York and New England, Holt served as a 1st lieutenant and captain in the 1st Virginia Regiment.

Dunmore took the seized press and began publication of his own paper from on board the ship William. From here, he published his proclamation which offered freedom to slaves and indentured servants of masters who were found to be in rebellion. The first issue of Dunmore’s version of the Virginia Gazette was be printed on November 25, 1775; the paper ran for approximately six months. In December 1775 Dunmore was defeated at Great Bridge, Norfolk would was burned on New Year’s Day 1776, and the British would not return to Virginia until May 1779.

[1] Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, April 20, 1775, available from https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/15430

[2] Victor Hugo Paltsits, John Holt, Printer and Postmaster: Some Facts and Documents Relating to His Career (New York: New York Public Library, 1920), 24.

[3] Ibid, 2.

[4] Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism (New York: Public Affairs, 2006), 126.

[5] The Journal of Occurrences, attributed to Samuel Adams and William Cooper, first appeared in the October 13, 1768 edition of the New York Journal. Written from the American perspective, the Journals were a series of articles that chronicled Boston’s occupation by the British Army and were often exaggerated to add to the propaganda effect. Martin J. Manning and Clarence R Wyatt, eds., Encyclopedia of Media and Propaganda in Wartime America, Volume 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2011), 71-72.

[6] A History of the Virginia Gazette, www.vagazette.com/services/va-services_gazhistory-story.html

[7] Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, April 20, 1775.

[8] Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, June 15, 1775.

[9] Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, July 5, 1775; August 16, 1775.

[10] Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, August 2, 1775.

[11] Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, September 9, 1775.

[12] Pinkney, Virginia Gazette, September 7 and September 14, 1775; Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, September 6, 1775.

[13] Pinkney, Virginia Gazette, September 14, 1775; Dixon and Hunter, Virginia Gazette, September 16, 1775.

[14] Mathew Squire to John Hunter Holt, September 9, 1775, and Holt to Squire, Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, September 13, 1775.

[15] Virginia Gazette, or Norfolk Intelligencer, September 20, 1775.

[16] Lord Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, October 4, 1775, in William Bell Clark, ed. Naval Documents of the American Revolution, volume 2 (Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1966), 167.

[17] Dixon and Hunter, Virginia Gazette, October 7, 1775.

[18] Lord Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, October 4, 1775, in Clark, Naval Document, 167.

[19] John Page to Thomas Jefferson, November 11, 1775, ibid, 991; “Address of the Common Hall of the Borough of Norfolk to His Excellency Lord Dunmore, Sept. 30, 1775,” Virginia Gazette (Purdie), October, 13, 1775.

[20] Lord Dunmore to the Common Hall of the Borough of Norfolk, October 3, 1775, Virginia Gazette (Purdie), October 13, 1775.

Recent Articles

John Dickinson and His Letters

North of America: Loyalists, Indigenous Nations, and the Borders of the Long American Revolution

The Two “Empires of Liberty:” The Fascinating Story of an American Phrase

Recent Comments

Ms. Spiegel, This is so beautifully done, IMHO, that I would love...

From your review, the naval and military professors produced an excellent primer...

Thank you, D Malcolm and good luck on your dissertation. In addition...