British Lieutenant Richard Williams was one of the few artists to document the siege of Boston from 1775 through 1776. He created maps, sketches, and watercolors of the places he visited. Today, this collection of imagery is in high demand by museums and private collectors because it gives us a rare glimpse of the war. In addition to his artwork, he kept a diary filled with his thoughts and drawings. The journal gives insights into how he made his art and the daily lives of British soldiers.[1] The items Williams left behind offer us a unique perspective on Boston and its residents during the siege.

Before Williams made maps and views of the colonies, he traveled in Europe. His diary, begun in January 1774, recounts his adventures and features sketches of things that caught his eye: architectural details, a German count, and elaborate clocks. Williams honed his artistic skills under the direction of Paul Sandby, who was also a mapmaker and landscape artist, at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich.

In late April 1775, twenty-five-year old Williams left for Boston to join his regiment that had already been in America for two years, the 23rd Regiment of Foot, the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He declared the coffee on board his ship to be “very good” and recounted attempts to catch sharks and porpoises, perhaps for some fresh sustenance.[2] While Williams’s trip across the Atlantic probably resembled that of many other soldiers, his diary has left us with impressions of these everyday experiences.

The journal allows us to see Williams as a person rather than a nameless soldier. On June 2, his ship neared Nova Scotia. A wounded bird flew on board and he welcomed it. He wrote:

Wellcome to our hospitable care my little featherd friend. Wellcome, for know that Pity & soft compassion dwell within a Soldier’s breast, driven from thy native shore by some rude blast, thy feeble wings could not long withhold thee from the threatening waves when that kind providence which or’elooks the world, and often frees us from the mouth of danger brought thee to our Vessel.

Williams’s sentiment for the small creature is poignant. His words might have reflected his own concerns about the wind carrying him away from his own “native shore.” Later he noted that a fellow soldier put the bird in a box to keep it warm, but it was found dead the next day. Williams lamented the death and sketched a memorial portrait of the bird, which suggests it was a chestnut-sided warbler.[3]

On June 7, as the ship neared Massachusetts, the soldiers encountered fishermen and learned about the battles of Lexington and Concord. Williams recalled that they said “we shou’d none of us live to return again,” which “brought a hearty damning on the poor fisherman” from his fellow soldiers.[4] Even before Williams landed, he experienced the colonists’ animosity.

By the time Williams arrived in Boston on June 11, the British had been confined to the city after their retreat following the action at Lexington and Concord in April. Williams entered a city surrounded by Gen. George Washington’s American soldiers. He reflected on the scene: “what a country are we come to, Discord, & civil wars began, & peace & plenty turn’d out of doors.” Despite his dismay about the continued conflict, Williams was glad to be in Boston. He declared “the Land was a pleasing object after six weeks of absence from it.”[5]

Williams was glad to leave the ship because his duties were tied to the land. As a cartographer and artist, he mapped the Boston area for local military leaders and London officials soon after his arrival. Williams took stock of the city from Beacon Hill, where he had a better view of the rebellious colonists across the Charles River in Cambridge. Of the city, Williams concluded that “Boston is large & well built, tho’ not a regular laid out town. it has several good streets, the generality of houses are built of timber & mostly with their gabel ends to the street.” He thought, however, the area had seen better days “before the present unhappy affairs” when “it was livly and flurishing.”[6]

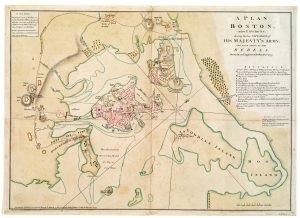

Williams used the view from Beacon Hill to draw his maps and panoramic sketches. He likely drew the Plan of Boston and its Environs Shewing the True Situation of His Majesty’s Troops from this vantage point. The manuscript map depicts the American and British positions in October 1775. Williams noted that he “went so far as our advanced post at a house in the road towards Roxbury,” which is southwest of Boston, but he never ventured beyond the British lines.[7] His map, therefore, reflects his view from the hill along with information he gathered from others. Fortifications were colored yellow for the rebels, and green for the British. Camps, like the one for British soldiers on the Boston Common, are red.[8]

Williams’s map demonstrates the geography that made the siege possible for the newly organized American troops. In the eighteenth century, the city of Boston was practically an island. Only one thin strip of land—referred to as the Boston Neck—connected the city to the rest of Massachusetts. This geography facilitated a large harbor, which helped make the city one of the busiest colonial ports. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Bostonians filled in much of the bay. Today the city barely resembles the outline on Williams’s map.

British military and political leaders had commissioned Williams to make maps and sketches so that they could best formulate their strategies. Williams sent this map of Boston to London, possibly in a group that he noted sending on July 28, 1775. [9] The map was engraved and printed less than two weeks before the British army evacuated the city on March 17, 1776. By the time the maps could be widely consulted, they practically became irrelevant. The delay between Williams’s initial sketches and their publication illustrates the challenges the British government faced as they orchestrated a war across the Atlantic Ocean.

As Williams learned more about the conflict, he wrote about his impressions of its origins. He noted, “The immediate and pretended cause of all these troubles now broke out in N. America is assigned by the artful leaders of this people, to the usurpd authority of the Britis[h] Parliament.”[10] Rather than a sincere desire for liberty, Williams believed the leaders of the revolution wanted more power. He thought the colonists had “not in the least deviated from the steps of their ancestors, allways grumbling & unwilling to acknowledge the authority of any power but what originated amongst them.”[11]

In addition to mapping Boston, Williams painted panoramic watercolors of the landscape. The pictures are aesthetically pleasing even as they offer important details about fortifications and encampments. From his perch on Beacon Hill, he created A View of the Country Round Boston, Taken from Beacon Hill with sketches of the city’s churches, homes, and British encampments.[12] At the bottom of the scene, Williams included a key to identify fortifications like Castle William and the “Redoubts of the Rebels.”

Sometimes Williams made multiple impressions of the same scene. This watercolor offers a view of the Boston neck and house of John Hancock, a merchant and signer of the Declaration of Independence who would later become the first governor of Massachusetts.[13] Two British officers stand in the foreground and point to the colonists’ encampments. The scene appears more like a bucolic landscape rather than a portrait of war. In contrast, a second watercolor of the same view labels the details that officials needed to know: the rebels’ lines on the other side of the Charles River, British encampments, and the road to Cambridge.[14]

The landscape views that Williams labeled with crucial details were sent to London and became part of the collection of King George III, who reigned from 1760 to 1820. In addition to using maps to influence the course of the American war, the king was an avid collector of maps and views. The British Library now houses these pieces as part of King George III’s Topographical Collection.

For the first time, the British Library has loaned Williams’s work for display in the city that Williams captured on paper. The Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library features the map and watercolors in their current exhibition We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence. More maps and views by Williams can also be viewed online in the American Revolution Portal database, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

One reason why Williams’s images are so valued is that we have very few images of the Revolutionary War. Today we have instant access to photographs and videos of conflicts, but the first few war photographs were not taken until The Crimean War (1853-1856). By the time the Civil War began in 1861, a corps of photographers took war views to sell to the public. Eighteenth century public imagery, in contrast, often consisted of engravings. Because colonists had limited access to engraving supplies and trained artists, most of the imagery that circulated in the colonies and early republic was created in Europe.

Lt. Richard Williams diary ends mid-sentence during his September 4, 1775 entry. He evacuated Boston in March of 1776 with the rest of the British troops and sailed for Nova Scotia, where he continued to capture the landscape with his watercolors. Shortly after his arrival, he became ill and went back to Britain. A death announcement from London’s Morning Post & Daily Advertiser for May 8, 1776 tells us that he arrived but died in Cornwall on April 30.

Although Williams died young, the unique maps, views, and diary he left behind offer valuable insights into life during the siege of Boston. Besides the few Boston and Cambridge residents who remained, soldiers like Williams were the only ones who could document experiences of the siege. These now treasured maps and views have helped thrust Williams and his impressions of the siege into the spotlight.

[1] The Grosvenor Rare Book Room at the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library houses the original diary. Parts of it were transcribed and published as Jane Van Arsdale, ed., Discord and Civil Wars: Being a Portion of the Journal Kept by Lieutenant Williams (Buffalo: Easy Hill Press, 1954).

[2] Diary of Richard Williams, May 18-19, 1775, 67 and June 5, 1775, 71-72.

[3] Williams, May 18-19, 1775, 69-71.

[4] Williams, June 7, 1775, 72-73.

[5] Williams, June 11, 1775, 74-76.

[6] Williams, June 12, 1775, 76-79.

[7] Williams, June 15, 1776, 80.

[8] [Richard Williams], “A Plan of Boston and its Environs Shewing the True Situation of His Majesty’s Troops and Also Those of the Rebels, Likewise All the Forts, Redoubts and Entrenchments Erected by Both Armies,” 1775, Manuscript, pen and ink and watercolor, 18 x 26 inches, British Library, Additional Mss. 15535.5.

[9] Williams, July 28, 1775, 117.

[10] Williams, June 15, 1775, 81.

[11] Williams, June 15, 1775, 82.

[12] Richard Williams, “A View of the Country Round Boston, Taken from Beacon Hill…Shewing the Lines, Redoubts, & Different Encampments of the Rebels Also Those of His Majesty’s Troops under the Command of His Excellency Lieut. General Gage, Governor of Massachuset’s [sic] Bay,”1775. Manuscript, ink and watercolor, each 7 x 19 inches, British Library, King George III Topographical Collection, 120.38.

[13] Richard Williams, [Boston Neck, with the British lines and John Hancock’s house], 1775, watercolor, 17×47 cm, Richard H. Brown Revolutionary War Map Collection.

[14] Richard Williams, [View of the country round Boston taken from Beacon hill], 1775, watercolor, 17×47.6 cm, British Library, King George III Topographical Collection 120.38.c. Find out more about Williams and the mapping of the American Revolution in the forthcoming book: Revolution: Mapping the Road to American Independence, 1755-1783. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, October 2015.

One thought on “Richard Williams Maps the Siege of Boston”

Allison,

Thank you so much for a great article describing the wonderful work by Richard Williams, along with all the interesting links. It is, indeed, beautiful stuff! Since I love maps of these times, the Brown book you recommended in note 14 has just been ordered from Amazon – a little pricey, but certainly looks like a great resource.

Thanks again.