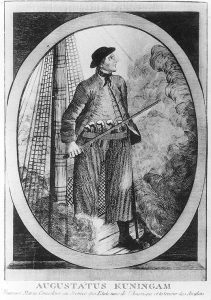

Shortly after the onset of the Revolutionary War, Americans started to harass British commercial shipping close-to-home. One ship captain who engaged in this type of naval warfare was Gustavus Conyngham. He was credited with the most ships apprehended, but received little gratitude, remuneration or recognition in maritime history, and in performing his service, he may have been the Revolutionary War’s inadvertent American pirate.

The Immigrant and Charming Peggy

Conyngham was born in County Donegal, Ireland in 1747 and his family immigrated to America in 1763. Conyngham learned mariner’s skills as an apprentice to a Captain Henderson.[1] He later became a captain in his own right and was invited to join Philadelphia’s Society for the Relief of Poor, Aged & Infirmed Masters of Ships, known locally as the “Sea Captain’s Club.” In 1773, at the age of twenty-six, Captain Conyngham married Philadelphia’s Anne Hockley. The intelligent articulate Mrs. Conyngham would become a vital asset later in his life.

The Philadelphia shipping firm Conyngham and Nesbitt Company, partly owned by a cousin, gave Conyngham command of the brigantine Charming Peggy. The Maryland Council of Safety contracted Conyngham and Nesbitt Company to obtain desperately needed gunpowder and other military equipment. In September 1775 Conyngham sailed to France to obtain the supplies and hoped to smuggle them back to America.

In November he arrived at Dunkirk and tied up adjacent to a British transport under repair. The port’s powder magazine was close by, but getting barrels of powder onboard in the shadow of a British ship presented a problem. In his attempt to move the precious cargo quietly at night, a crewman on the transport became suspicious. He alerted his captain who, in turn, told the local British consul about Conyngham’s suspected deceit. The consul then contacted England’s Ambassador to France, Lord France David Murray Stormont.

Stormont, increasingly aware that the French public seemed supportive of the Americans, demanded that the French Foreign Minister do something about Conyngham who appeared to be on a clandestine mission to obtain arms for the rebels. French officials boarded Charming Peggy, but Conyngham learned of the raid’s plan and jettisoned the powder. Without proof of contraband, the French could not hold Charming Peggy’s captain, so he sailed for Holland minus the needed cargo and continued to Texel Island. Dutch businessmen brought two vessels to Texel loaded with the desired cargo plus “flints, medicene, [and] cloathing.”[2] Contrary winds detained Conyngham’s departure and then misfortune struck. A Charming Peggy crewman told the local British consul about the vessel’s quest. Charming Peggy was seized and Conyngham arrested. Ever alert, Conyngham and some of his crew disarmed the guards that had been placed onboard. In danger of recapture, the captain and crew made for the nearest port with the intention of selling Charming Peggy to the Dutch government. Because of local corruption, Conyngham was never paid for Charming Peggy and was thus forced to search elsewhere for another ship to obtain and deliver the contracted cargo.

Ship-less

Benjamin Franklin, the American Minister to France, was about to implement General Washington’s plan of asymmetrical warfare against British shipping to influence commerce, maritime insurance rates and British morale while keeping more of His Majesty’s vessels on patrol near the British Isles, away from North American waters. Conyngham, who made his way to Paris was recommended to Franklin as a potential Continental Navy captain, one who might be effective in harassing nearby British shipping. Franklin filled out a blank Continental Navy commission for Conyngham dated March 1, 1777. Signed by John Hancock, the President in Congress, no written expiration date or restrictive clause was contained in Franklin’s blank commission.[3]

At the time, American Commissioner Silas Deane was making lucrative commercial dealings with French businessmen and likely saw Conyngham perhaps as a privateer captain in whom he might invest. Privateering was an important Revolutionary War activity that authorized a vessel, but not its captain, to conduct privateer operations outside the borders of its home nation and profit from the sale of cargos and prizes taken. Ship owners applying for a letter of marque provided a detailed description of the vessel, its armament, and posted a bond to assure that vessel and enterprise would observe international laws and customs.[4] The vessel could attack the enemy within the time limits of the letter of marque. Failing to comply with the obligations meant the letter could be revoked, prize money refused, the bond forfeited, and legal damages could be sanctioned. First issued by state (colonial) legislatures on April 3,1776, the Continental Congress also issued national letters of marque to capture British vessels and cargoes.[5] Whether these letters were issued as blank documents so that ship owners could apply them to vessels of their choosing is not documented. Blank congressional privateer commissions might have been obtained from Deane.[6] Privateering during this time was both potentially lucrative and dangerous. Britain declared America’s revolutionary activities as illegal, thus privateers were considered pirates and, if caught, punished by hanging. No captured Revolutionary War privateer actually met death in this way.[7]

Surprize

After Commissioners of the United States learned that Conyngham was seeking a ship, he was given command of the lugger Peacock, an armed vessel he believed was purchased and fitted by order of these commissioners. Luggers and cutters, relatively swift and quite seaworthy crafts in turbulent waters, were good vessels for smuggling and interdicting shipping and readily available in Dunkirk. Conyngham renamed Peacock, the Surprize and recruited his crew largely from idle American sailors detained in French and Belgium ports, plus an assortment of foreign nationals. At the request of Compte de Maurepas, Prime Minister of France, no French sailors were included.[8] The French were serious about maintaining strict neutrality. Conyngham considered Surprize to be a Continental Navy warship and his crew were to be “govern’d by the regulations made for Seamen in the Continental Service” and not owned privately.[9] Conyngham said in a narrative dated March 1779 that he “Went on a cruze under my former Commission U.S. Navy.”[10] Adding to this perception, one of Conyngham’s first lieutenants, Matthew Lawler, later wrote to Navy Board member Timothy Pickering stating that, to his knowledge, he served on a “continental Vessel.”[11]

Instructions dated 15 July 1777 from another American Commissioner stationed in France, William Carmichael, put a sharper focus Conyngham’s mission. In part they stated, “. . .you should not cruise against the Commerce of England, I beg and intreat you . . . that you do nothing which may involve your security or occasion Umbrage to the Ministry of France. Not withstanding which your stock is not abundant . . . or If attackd first by our Enemies, the circumstances of the case will extenuate in your favor of your conduct . . ..” in essence you may defend yourself. But Carmichael went on to say that he was to proceed directly to America to deliver dispatches as soon as possible.[12] Conyngham ignored the order and set out to do more damage to British shipping.

Surprize sailed from Dunkirk into the narrow English Channel in May 1777 where he captured two vessels while at sea: a British mail packet Prince of Orange carrying mail to the Dutch seaport of Helvoetsluis and the brig Joseph carrying a cargo of wine. On May 9 he ordered his prize crews to make for land with the two prize vessels where they were to be repaired and sold. When Surprize, accompanied by the prize vessels approached Dunkirk’s harbor, they encountered a pair of British Navy ketches. The British vessels rammed him multiple times, in the hope of goading Conyngham into a fight. He did not fire a shot and decided to use the courts as a weapon and proceeded to the protection of the neutral harbor. Conyngham planned to sue the British government for payment of damages to his ships once they got safely to shore and keep his prizes as well. His seemingly logical plan failed miserably.

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht between France and England explicitly closed the ports of either power to the enemies of each other. Thus outraged, the British Ambassador vigorously protested to Compte Charles Gravier Vergennes in Paris objecting to the seizure of two of His Majesty’s vessels in the English Channel. To emphasize the point, the British sent the 18-gun sloop Ceres to blockade Conyngham and his entourage. Thus the French had no choice. They arrested Conyngham and his crew and in doing so, seized Surprize and confiscated his Continental Navy commission papers.[13]

Stories about Conyngham’s [aka “Cunningham” in British broadsheets] seizure of the British vessels appeared in English newspapers. The British public had been told that they were easily winning the war against the rebelling colonies, but now this premise was being questioned. (In the press political cartoons of Conyngham as a pirate would heavily weigh on the American in the future.)

The British Admiralty sent two additional sloops of war to Dunkirk to join Ceres to aid in extraditing the Irish expatriate and his crew to England for trial. Fortunately Franklin had garnered sympathy for the American cause within the French court of Louis XVI. Conyngham, his crew and the Surprize were released, but the Irish American was now a notorious criminal in the eyes of the British. A new Continental Navy commission was delivered to Conyngham dated May 2, 1777, dutifully signed by Hancock. It validated Conyngham’s service in the Continental Navy and replaced his earlier commission document that had been seized and re-certified him as a captain in the Continental Navy.

Revenge

William Hodge, an American agent based at Dunkirk, sold Surprize to a French woman with Franklin’s approval then purchased the cutter Greyhound built for speed. To make the purchase seem innocuous, Hodge drew papers that stated that Greyhound had then been resold to an Englishman named Richard Allen. Conyngham appeared uninvolved in Hodge’s dealings.

Everything seemed quite correct. Once Captain Allen sailed Greyhound well clear of Dunkirk’s harbor, Allen “miraculously” became Gustavus Conyngham. Conyngham took command and renamed her Revenge probably assuming his appointment as a Continental Navy officer made the cutter Revenge a Continental Navy ship. According to a March 1779 letter Conyngham stated, “[I continued in Comd of her [Revenge] – Went on a cruze under my former Commision U.S. Navy.”[14] Now at sea, Revenge armed with 14 cannon and 22 swivel guns and a crew of 106 (mostly veterans of Surprize) would create havoc with British shipping, capturing or destroying many of their sparsely armed smaller vessels.

When Conyngham took Revenge to sea on July 16 several British vessels chased and fired on him, but he escaped. The American captain later captured four British small merchant ships; among them was a mail packet with many letters onboard. Stories of the shipping captures caused great concern in London. During the years 1777-1778, the maritime insurance rates increased by twenty-eight percent, “higher than at any time in the last with France and Spain.”[15] “Not only did the British merchants ask for protection of war ships for their merchantmen on distant voyages, but they even demanded escorts for linen ships from Ireland to England.”[16] British cargoes were switched to French and other neutral nation vessels.

In a questionable decision, Conyngham landed his prizes at Dunkirk once again. An infuriated Stormont again protested to Vergennes. The French ministry ordered Conyngham’s prizes returned to the British owners and imprisoned the American and his crew. William Hodge was incarcerated in the Bastille for deceiving the French government after outfitting a raider in the guise of a merchantman.[17] Thus the English were temporarily placated having imprisoned the pirate Conyngham and Hodge the outlaw smuggler.

Hodge gained his freedom by the intervention of Franklin or Silas Deane, each of whom had political connections in the French Court. About this time, enmity between Arthur Lee and Deane started to surface overtly and Conyngham’s ventures were given as one of the reasons for the animus. Deane as Commissioner was asked to procure arms for the Revolutionary War from European powers. Profiting from these dealings, although considered unlawful by today’s standards, was normal business at the time. Deane, in particular, had dealings with playwright and staunch American supporter Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais. Lee, apparently resentful of Deane’s successes, initiated a campaign to denigrate Deane’s character, accusing him with disloyalty, embezzlement, and charging for supplies that the French had given as gifts to America. These accusations were never verified, but they helped lead to Deane’s ruin.

Conyngham and his crew eventually gained release from the French authorities and Revenge set sail, this time for the mouth of the Thames River. He scoured the shipping lanes off the English coast for quarry capturing the schooner Happy Return, two brigs Maria and Patty, and merchantman Northampton. Conyngham sailed west, rounded Scotland’s Shetland Islands and sailed south near Ireland’s west coast. The British were increasingly annoyed at Conyngham’s piratical actions. Stormont now asked Vergennes to issue orders to arrest the “Dunkirk pirate” if he returned to France.

Meanwhile Conyngham was having difficulty finding British vessels that could be easily subdued, so Revenge headed south. Nearing the Spanish coast, Conyngham encountered a British warship. The ships exchanged several harmless shots, but Revenge had suffered some storm damage off the British Isles that affected her maneuverability. Feeling vulnerable, Conyngham decided to avoid the fight. Before long the British Admiralty learned that Conyngham had exchanged gunfire with a British warship off the Spanish coast. Assuming that he was seen taking refuge in Spain, they now sent a diplomatic protested to the Spanish government.

On September 1 the Revenge arrived at El Ferrol, on the northwestern coast of Spain. Conyngham had a new masthead crafted and other repairs performed supervised by local American agents. In a document concerning payment he stated: “I pledge in case of need, my person, my belongings present and future, and generally and especially the armed sloop-of-war the Revenge which I command and the prizes and ransoms that I have already taken in virtue of a commission from the Congress. . . . .,” further evidence that Conyngham believed that he was in command of a Continental Navy ship and took personal responsibility for the vessel’s wellbeing.[18]

Concerned about maintaining Spain’s neutrality status, the El Ferrol governor ordered Conyngham to leave in early October 1777. Cruising off Cape Ortegal east of Bilbao, Revenge detained the French brig Graciosa en route from London to La Coruña with dry goods fully insured in England. The British merchants were shipping goods via a “neutral bottom” in order to avoid capture by the now notorious “Dunkirk pirate.” Taking a nonaligned French vessel into a neutral Spanish port was a major diplomatic blunder. Once the prize crew sailed the French vessel to St. Sebastián, Conyngham’s men were jailed and their prize brig Graciosa was quickly returned to her owners.

The report of this incident reached Paris further inflaming the enmity between Lee and Deane. The two American commissioners were in rare agreement, both being appalled by Conyngham’s lack of judgment. Deane berated Conyngham in January 1778 writing, “ Every such adventure gives our Enemies advantage against us by representing us as persons who regard not the Laws of Nations. . . .Your Idea that you are at Liberty to seize English Property on board of French or other neutral Vessels is wrong; it is contrary to the established Laws among the maritime Powers of Europe. . . .”[19] The captain apologized concerning this diplomatic misdeed and dropped all claims to the captured vessel and its cargo. Yet he pointedly questioned if British naval ships could confiscate goods from American vessels, then Continental Navy vessels should be able to do the same. “Have we not a right to retaliate?”[20] Clearly Conyngham assumed he was acting under his Continental Navy captain’s commission and had the prerogative to engage the enemy. He also assumed that Lee was partly behind Deane’s letter of reprimand of him.

Conyngham continued his hunt for British shipping. The first vessel he captured and burned was a small tender from the 28-gun British frigate Enterprise. The mother warship gave chase, but the swifter Revenge sailed out of range of the British warship’s cannon. Five additional vessels surrendered to Conyngham through mid-March. These prizes were sent across the Atlantic to Newburyport, Massachusetts.

On February 6, 1778, the French signed the Treaty of Alliance that recognized the United States of America. Subsequently on March 17, 1778, the French government declared war on Great Britain making French ports safe-havens for Conyngham, but he found himself still sailing off neutral territory. Communications concerning political events were slow to circulate, particularly among those at sea.

Many Spanish merchants were increasingly sympathetic to the American rebellion, so Conyngham put into Cadiz, Spain around the end of March 1778. The British blockaded Cadiz harbor with two frigates, but Conyngham managed to sail past them at night. He headed for the Canary Islands where he captured and burned several more ships, all the while evading other British frigates that were ordered to hunt him down.

Conyngham next boarded the Swedish brig Henerica Sophia that was carrying a cargo of dry goods; her destination was the Canary Island port, Teneriffe. Previously Silas Deane had written Conyngham stating that only neutral vessels, “loaded with Warlike stores & bound to the Ports of our Enemy,” could be detained.[21] Dry goods could not be classified as “Warlike stores” and Teneriffe was certainly not an enemy port. The taking of this vessel was equivalent to the recently bungled Graciosa affair. This ill-considered action caused letters of rebuke about the “American corsair named Cunningham” from Vegennes, Franklin and other assorted foreign diplomats.[22]

The Henerica Sophia was the last ship that Conyngham captured in European waters. The daring American, however, was not done and now harassed shipping in the Caribbean. Revenge arrived in Martinique in late October. Conyngham went on to take five vessels in the Caribbean in November. At Martinique, Continental agent William Bingham cultivated a friendship with Conyngham. Bingham received a dispatch that Admiral Comte d’Estaing was bringing a French fleet and troops to Martinique, but he was notified that some British vessels were also in the area. On December 28 Bingham sent Conyngham to warn d’Estaing that a British squadron was likely to the windward of the French fleet and thus vulnerable in an attack. Duly forewarned, d’ Estaing engaged and dispersed the British force. Revenge, a mere messenger, was a distant spectator and returned to the port of St. Pierre on January 2, 1779. This was an important Martinique seaport, a place to exchange smuggled arms into specie. About this time Bingham noted that there was a large store of military supplies on hand. He asked Conyngham to deliver fifty chests of weapons to Philadelphia for the use of the Continental Army.

After being away from his family for three years, Conyngham was astounded by the firestorm of criticism and complaints he encountered when he arrived in America. The Marine Committee of Congress met in Philadelphia on January 4, 1779 recommending, “that Capt. Conyngham give an account of himself.”[23] Some former crewmen who preceded him home claimed that they had not been paid their promised wages. He was also unaware that he had become embroiled in scandals surrounding Deane, Arthur Lee and his brother Richard Henry Lee, now chair of congress’s Marine Committee, set out to disgrace Deane. They alleged that both Surprize and Revenge were privateers and several partners along with Deane had profited handsomely from the prize money derived from Conyngham’s cruises. Conyngham’s initial cruises occurred when France was trying to maintain political neutrality, thus forcing him to disguise his prizes even though his actions were approved and encouraged by American commissioners. The resulting irregular marine warfare proved to be an effective strategy during the early stages of the Revolutionary War. Conyngham claimed his motive was to harass British shipping in their dangerous home waters. Any ensuing financial gains were secondary to his goal. Conyngham’s arguments gained sympathy, if not complete success in all quarters.

Upon his return to the United States, Conyngham was no longer captain of what he assumed was the “Continental Navy Cutter Revenge.” The merchant firm of Conyngham and Nesbitt purchased Revenge, a move completing a figurative maritime circle. The obvious choice for her captain was Gustavus Conyngham. The State of Pennsylvania, an unsuccessful bidder, chartered Revenge for a fortnight to protect the city’s commerce on the river under a letter of marque and as a lawful privateer. By the end of April 1779, the letter of marque charter expired. When Revenge set out to the Capes of Delaware on a private cruise, it was without any governmental “paper cover.”

Prisoner

While cruising in waters off New Jersey in May, Conyngham encountered the 20-gun HMS Galatea. Revenge, out-gunned and out maneuvered, was forced to surrender. Sticking to maritime protocol, Galatea’s Captain, Thomas Jordan RN, requested Conyngham’s papers. Having none, Conyngham was placed in irons. Once Galatea docked in Tory New York, Conyngham was first taken to a wretched prison hulk anchored off Brooklyn, then jailed at the provost’s prison where he was weighted down with fifty-five pounds of chains that were fastened to his ankles, his wrists and an iron ring secured about his neck.

Starved and mistreated for some weeks, Conyngham was eventually brought before Commodore Sir George Collier. Collier ordered Conyngham extradited to Britain for trial and probably to be hanged. Jeered by a loyalist crowd, Conyngham was first paraded through the streets on a cart to the dock and then rowed to the British packet Sandwich bound for London. Finally he was placed in the grimy foul-smelling hold for his voyage to England.[24] Before Sandwich sailed on June 12, 1779, the American was given the opportunity to write a letter to tell his wife Anne of his situation. Conyngham landed at Falmouth, and then he was sent to Pendennis Castle bound by heavy irons and confined in a small windowless cell sealed with an ironbound bolted door.

Meanwhile Anne Conyngham used her husband’s letter describing his inhumane treatment to appeal to Congress to obtain her husband’s release. She contended that the British conduct violated international prisoner of war protocol. Early in the war Stormont had been asked that Americans held in British prisons be subject to an exchange of prisoners to which he condescendingly replied, “The King’s ambassador receives no application from rebels, unless they implore his majesty’s mercy.”[25] Philadelphia’s Society for the Relief of Poor, Aged & Infirmed Masters of Ships, learned of Conyngham’s plight and angrily protested His Majesty’s treatment of Conyngham before the Continental Congress.[26] In retaliation Marine Committee ordered Lieutenant Christopher Hele RN, formerly of HMS Hotham and confined in a Boston prison, placed in conditions similar to that of Conyngham.[27] This apparently brought the issue to the Admiralty’s attention and led to Conyngham’s imprisonment at Mill Prison (Old Mill) in Plymouth and he was now regarded as an exchangeable prisoner. At Old Mill, if one committed “the least fault as they termed it, [one would spend] 42 days in the dungeon on the half of the allowance of Beef & bread — of the worst quality. . . .dogs, cats rats even Grass eaten by the prisoners, thiss [sic] hard to be credited, but is a fact.”[28]

While at “Old Mill,” Conyngham tried several escapes. Once he nonchalantly walked out of the prison gate with a group of visitors, but was caught after he started to go his own way. In another attempt, he dressed in a dark suit, and while wearing wire-rimmed spectacles in the disguise of a visiting doctor, he pretended to be engrossed in a book and walked through the prison gates. Unfortunately a prison tradesman recognized Conyngham and he was recaptured. On one particular stormy day, when the guards were preoccupied with the weather, he slipped by the sentries again, but was soon captured. Finally on November 3, 1781, Conyngham succeeded in escaping with a group of about fifty other Americans who had dug a tunnel under the prison wall.[29]

Conyngham and a few fellow escapees eventually crossed the channel to Holland. John Paul Jones was at the Texel having recently docked there after his renowned Bonhome Richard/Serapis sea battle. Conyngham contacted Jones hoping to find passage home. When the two men met for the first time, Jones greeted Conyngham warmly. The two American “rogues” were briefly united onboard Jones’s new command, the frigate Alliance. Both had successfully fought the British in their home waters and were now considered pirates in the English popular press. Jones wished to continue his raiding, so Conyngham left Alliance and sailed to Philadelphia on Hannibal whose crew included ninety-five fellow escapees from British prisons. [30]

The Itinerant Mariner Returns

The Revolutionary War finally ended with the signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Conyngham had been given two naval captain’s commissions, signed by the President of Congress and one personally presented by the esteemed Benjamin Franklin, but Congress now ruled these commissions were considered temporary. Conyngham’s captain’s rank in the Continental Navy was denied and they refused to pay him for his naval service.[31] A persistent Conyngham went on to spend seven years attempting to persuade Congress to give him what he considered his federal back pay. Even Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton tried and failed to advance Coyngham’s claim through Congress.[32]

Gustavus Conyngham served the cause of American Independence with distinction and endured many hardships as an English prisoner. Because he had been issued a Continental Navy commission, he assumed his actions were within the rules of maritime warfare. According to official records, neither Surprize nor Revenge is listed as Continental Navy or privateer vessels. In summary, Conyngham had fought under an “expired” naval commission and neither of his vessels were Continental Navy or letters of marque. Therefore his actions were, according to maritime law, technically that of a buccaneer. Legally Conyngham could have been tried and, if convicted, ingloriously hanged —albeit as an unwitting pirate.

Gustavus Conyngham died in Philadelphia on November 27, 1819 at seventy-two. Conyngham took thirty-one prizes, more than any other American naval officer in the Revolutionary War.”[33] It should be noted that none of these vessels were British men-of-war therefore his actions were like those of a privateer. He also, perhaps unwittingly, became a pawn in the feud between Deane and Lee. Captain Conyngham was daring, imaginative, resolute, and resilient, but also naïve. His Revolutionary War captures, whether legal asymmetric warfare acts or guileless piracy, impacted British morale at home, tempered their commercial maritime activity and contributed to the realization of America’s independence.

[1] Henderson’s given name is not recorded.

[2] Robert Wilden Nesser ed., Letters And Papers Relating to the Cruises of Gustavus Conyngham, A Captain Of The Continental Navy 1777-1779, (Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing, 2006). 10.

[3] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham,1. Franklin and his commissioners recruited many outstanding European officers to be appointed generals including Gilbert du Motier Marquise de Lafayette, Baron Friedrich Von Steuben and Count Casmir Pulaski.

[4] The bonds were $5000 for vessels under 100 tons and $10,000 for vessels exceeding 100 tons.

[5] Library of Congress, Naval Records of the American Revolution, 1775-1788. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1906, 10-11.

[6] No documents written by or to Conyngham refer to his actions as privateering and serve as evidence that Conyngham did not think that he was acting as a privateer.

[7] Donald Barr Chidsey, The American Privateers: A History (New York, NY: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1962) 54.

[8] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 60.

[9] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 216-219.

[10] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham,11.

[11] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 223-224.

[12] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 64-65.

[13] The American naval captain’s commission was taken to Versailles, not to be seen again for about a hundred and thirty years.

[14]Michael J. Crawford, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, vol. 10, 1996) 901.

[15] Wharton’s Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: Department of State, Vol. II,) 262 and 311.

[16] Edgar Stanton Maclay, A History of American Privateers (New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1899) xii.

[17] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 88.

[18] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 104.

[19] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 120.

[20] Crawford, Naval Documents, 11: 956-957, Conyngham to Lee 1/13/1778.

[21] Crawford., Naval Documents, 120.

[22] Nesser, Letters And Papers of Conyngham, 138, 148, 149. Also Franklin’s letter to Grand in Wharton’s Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution, Vol. II, 827-828.

[23] Library of Congress, Naval Records of the American Revolution, 93.

[24] Being hanged in public was a common punishment for pirates in England, although by the time of the reign of George III, it was less common. Perhaps Conyngham’s Irish ethnicity precipitated his extraordinarily cruel treatment.

[25] H. Hastings Weld, Benjamin Franklin: His Autobiography; with a Narrative of His Public Services (New York, NY: Harper and Brothers, publishers, 1848) 497.

[26] Library of Congress, Naval Records of the American Revolution, 110-111.

[27] Library of Congress, Naval Records of the American Revolution, 114 and Nesser, Letters And Papers of Conyngham, 184, 192.

[28] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 11.

[29] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 190.

[30] Nesser, Letters and Papers of Conyngham, 12.

[31] Library of Congress, Naval Records of the American Revolution, 197.

[32] Nesser, Letters And Papers of Conyngham, 213.

[33]E. Gordon Bowen-Hassell, Dennis M. Conrad and Mark L. Hayes, Sea Raiders of the American Revolution: The Continental Navy in European Waters (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy, 2003), 41.

4 Comments

I’m not an expert on dates, but Jones took the Serapis in 1779 and sailed it to Texel. He left Texel in the early part of 1780. You mention Conyngham escaping prison (1781) and meeting up with Jones shortly after in Texel (shortly after taking the Serapis).

Could you please clarify?

Thanks.

Thank you, Mr. Norton, for putting together this piece. The activities of the sea-borne Revolutionaries is yet another topic essentially unknown by most folk.

A couple comments: while the public and popular press in England certainly viewed the American seamen as pirates, the court system considered American privateers and crews of state and Continental navy ships to be traitors–worse than pirates.

Secondly, William Carmichael did not serve as a commissioner in France but, rather, as secretary to the commissioners, Arthur Lee, Silas Deane, and Benjamin Franklin.

Lastly, I suspect Conyngham’s prison experiences may have become blurred in your writing process and led to NLR’s previous comment. In your piece, it reads like he served time at MIll only once but, in reality, he went there on two different occasions. After escaping from his first term, he met John Paul Jones at Texel and some time after that, fell into British hands again. I believe he became part of an exchange after that capture.

While reading in Benjamin Franklin’s papers, I came across an interesting sidelight to Conyngham’s story. It seems the privateer that captured Conyngham the second time had as part-owner one Samuel Hartley. Hartley had long been working with Benjamin Franklin in advertising the plight of American prisoners in England and in supporting them. He regularly made statements in parliament and appeared before the Commission for Sick and Hurt Seamen and the Exchange of Prisoners of War, the part of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty in charge of prisoners.

Some months earlier, Franklin had secured the release of the captain and mate of a ship owned by Hartley that had been taken by the French. Franklin called in his marker and Hartley wrote to his co-owner asking that Conyngham be released rather than put in prison when he arrived in port. Regrettably for Conyngham, the letter arrived too late and he ended up back in prison.

Prof. Norton,

thank you for your article. I have in my hands today the diary (letter record/journal) of Gustavus Cunningham himself (Nov 1777 to March 1779). It is inside a folder of the Court Papers and Prize documents from the capture of his ship The Revenge in April 28th 1779 belonging to the High Court of the Admiralty. It is such a joy to read of him, and of his adventures in your article.

It is document 10 in said folder HCA/32/441/7 Prize Papers. The National Archives, Kew. (UK)

Gratefully,

E B Bronheim