Within a decade of the passage of the Stamp Act, England and her colonies would go to war. The Act would have a profound effect on both Parliament and the American colonists. Both sides would be tested and each was unwilling to yield from their position. In the end, both would claim victory. Only George Grenville, creator of the Stamp Act, was considered the loser. It seemed the battle was over, but the war had not yet begun.

By 1763, the Seven Years’ War had ended. Although England was victorious, the country was faced with a huge financial debt. Money was needed and fast. “Responding to the widely held view that America was largely to blame for the increase in the national debt as a result of the Seven Years’ War, the Grenville ministry determined to help meet expenditures by raising revenues in America.”[1] England was now looking toward America as the solution to her problem.

During that same year, George Grenville would replace John Stuart as Prime Minister. Grenville would now be the man responsible for resolving England’s debt. The people of England had carried the colonies for long enough. “England was already groaning under the burden of taxes; something, it was clear, must be done for her relief. Why not turn to the Colonies directly to account, it was reasoned.”[2] Grenville was faced with a tough task and many of the solutions suggested were not going to be popular with the colonies. For example, the Navigation Acts that had not been enforced for decades were now being revised. The colonies would have to pay heavier duties on imports. Also, the British Navy became much stricter when checking ships. Most importantly, specie was going to be the only form of payment allowed. Colonial money which had previously been accepted was no longer considered legal tender. The fact that there was a shortage of specie made the situation even harder for the colonists to swallow.

One option which Grenville felt would be acceptable by the colonies was a stamp tax. “After some debate it was felt that a tax levied in the form of a revenue stamp upon necessary papers would be at once easy to collect and hard to evade.”[3] The idea of a stamp tax was not new. Parliament had considered using this method in the colonies during the 1720s and late 1750s, but decided against it.

By 1763, times were harder and Grenville was determined to pass the Stamp Act. He had his reasons. “Such an increase in revenue would be relatively painless economically, because it depended on a growth of population and wealth, not upon additional burdens on individuals.”[4] For one, this was not a severe tax to ask colonists to pay. Also, since the colonies were being protected by British troops, they should pay for it. “Grenville’s common-sense was that those who benefited by a given service should at least help to pay for that service.”[5] Many in Parliament would be shocked with America’s reaction to the tax.

Two men were given the task of drafting the Stamp Act. Each was familiar with American affairs. One was Henry McCulloh, a land speculator with interests in North Carolina. The other was John Kempe, Attorney General of New York.[6] Kempe was secretly informing Parliament about issues concerning the colonies. Both McCulloh and Kempe worked separately on their proposals. Eventually Kempe’s idea was victorious. “Kempe’s plan, being more moderate than McCulloh’s, was more in accord with Grenville’s own view that the new revenue should be applied solely to the cost of colonial defence.”[7] Still, Parliament would not vote on the plan for almost a whole year.

Grenville, along with Parliament, wanted to receive more information concerning the colonies before voting on the Stamp Act. In addition, he was concerned with the constitutionality of the bill. He believed the colonists could not be trusted to tax themselves. In the past, they offered little support to England. “If the colonists would not express their consent, then they would have to bow to an omnipotent Parliament. The question of the right of Parliament to tax the colonies did not exist for Grenville.”[8] Grenville was willing to accept any ideas the colonies had to solve the problem. When they offered no response, Grenville believed the tax was then an acceptable solution to England’s debt. “Grenville ended by pointing out that the colonies themselves, even when asked, had failed to suggest any alternatives.”[9]

Parliament did not know whether, even though the colonists offered no solution to the problem, the Stamp Act would be an acceptable answer. By December 1764, the English government was receiving several petitions from America complaining about the Revenue Act. The colonists believed only their own assemblies could collect taxes. “For, as Sam Adams wrote: ‘If taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal representation where they are laid, are we not reduced from the Charter of Free Subjects to the miserable state of tributary Slaves? We claim British rights not by Charters only! We are born to them.’”[10] What could have been a warning signal to Parliament was instead overlooked as a minor disruption in political affairs.

The time had now come for Parliament to vote on the Stamp Act. “… on March 22, 1765 it became law. Accordingly, all legal and commercial documents, pamphlets, newspapers, almanacs, cards, and dice would be dutiable after November first.”[11] It was passed with a huge majority vote. The Act also carried penalties, such as fines for not having stamps, possible death if caught counterfeiting stamps, and illegality of documents without stamps.

Even before the Stamp Act was to go into effect some colonists were planning boycotts. “The local [New York] merchants signed non-importation agreements and the Sons of Liberty were organized to prevent the appointment of a local deputy to the stamp tax collector.”[12] Parliament was not expecting the colonies to react the way they did when the news arrived in America. “If prominent and well-informed colonists in London, some of them like Franklin and Ingersoll newly arrived from America, could not anticipate the violent resistance to the Stamp Act Grenville’s administration cannot be blamed for lack of foresight.”[13] Colonists were outraged and many began protesting. When the stamp distributors were announced for each colony, people started rioting, burning effigies, and in some cases vandalizing homes.[14] “No sooner were the names of the stamp distributors published in neighboring Provinces than similar disturbances followed.”[15]

Each colony’s governor and stamp distributor had trouble enforcing the act. In most colonies, stamps had to be consistently guarded and transported to different areas for fear of a mob uprising. In New York, Governor Colden believed he could enforce the Stamp Act. As soon as the stamps arrived though, a mob formed and began rioting. Mayor James’s house was destroyed and not until Colden turned over the stamps did the mob stop. The governor did not even receive support from England. “Although he had labored hard to execute the Act, the aged governor was reprimanded by an unsympathetic ministry for not having put forth still greater effort.”[16]

In Massachusetts, Governor Hutchinson faced even larger problems. Andrew Oliver was appointed and accepted the position of stamp distributor, but he would not last long. After he was hung in effigy and his home burned, Oliver resigned within a day. “The true-born SONS of LIBERTY are desired to meet under Liberty Tree at XII o’Clock This Day, to hear the Public Resignation under Oath, of Andrew Oliver, Esq; Distributor of Stamps for the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay… A Resignation? Yes.”[17]

Governor Hutchinson would not get off so easily. A few weeks following Oliver’s resignation, a second mob formed and burned the governor’s house to the ground. A reward was offered for any information on the mob and its leader, but no one came forward. Although Hutchinson was against the Stamp Act from the start, once Parliament passed it as legislation, the governor felt it was his obligation to enforce it. He believed the colonies should use persuasion and not violence when dealing with Parliament. This would cause Hutchinson to gain many enemies in America. “The colonies had come of age; and Thomas Hutchinson was still trying to play the role of guardian. The price of his mistake in 1765 was a house in ruins; the ultimate price was a life completed in exile.”[18]

John Hughes, eventually the stamp distributor of Pennsylvania, was also faced with a difficult problem. Throughout the summer of 1765, rumors had spread that he would be named distributor for Philadelphia. This would not be true for another two months. By September, a mob was ready to attack Hughes’s home. There he stayed waiting for the mob. Fortunately, his friends came to his aid to protect his house. “I for my Part am well arm’d with Fire-Arms, and am determin’d to stand a Siege.…There are now several Hundred of our Friends about street, ready to suppress any Mob, if it should attempt to rise…”[19]

In October of 1765, the stamps arrived in Philadelphia on the same day as Parliament’s appointment of Hughes as stamp master. Immediately the mob headed for his house. This time, Hughes was left with no choice. He was forced to sign a promise stating that he would not enforce the stamps. “Hughes signed [a statement] promising simply that he would not execute the Act until it was executed in the other colonies.”[20] This was still not enough for those who were against the Stamp Act. Hughes continued to receive threats stating that he should resign from his office, but he would not back down. He, like Hutchinson, felt Parliament was unjust in taxing the colonies, but also felt an obligation to follow orders.

Jared Ingersollwas also opposed to the Stamp Act. In fact, while in England, he met with Grenville and tried to persuade him against the tax. When Grenville did not back down, Ingersoll tried to reduce the number of items taxed, along with lowering the rate. “Though he had not succeeded in preventing the stamp tax, he had done more than any other man to reduce the size of it.”[21] Soon after, Ingersoll was offered the position of stamp distributor in Connecticut, which he accepted. He knew the people of Connecticut would be upset with the stamp tax, but thought he could make the process more bearable for them.

Ingersoll was quite surprised with the reaction he received when he returned to America. Letters published by his enemies in the newspapers attacked his character and accused him of treason. He was then asked to resign from his position and only did so when surrounded by a large mob. Ingersoll had to resign twice in front of the public. Afterwards, a letter he had written to England was questioned and again he was asked to pledge his alliance to America. “Actually his suggestion had been that if Parliament did not repeal the Act, they should at least reduce the rates.”[22] His career, like many others accepting the position of distributor, was ruined once the Stamp Act was repealed.

Parliament’s reaction was calm given the riots going on in America. The government decided to wait a few months before repealing the Stamp Act. “Rockingham and the other ministers wanted, according to Thomas, to hear what happened in America after November 1, the day the act would go into effect, before making further decisions.”[23] The members of Parliament wanted to give the colonies a chance to cool down and accept the tax instead of punishing them right away. Also, England did not send troops over to America to put a stop to the riots and enforce the tax. “In fact, for two compelling reasons the ministers never seriously considered sending regulars across the Atlantic in 1765.”[24] Most important for Parliament reaching this decision was money. The whole objective of issuing the Stamp Act was to increase revenue. If Parliament sent troops to America to enforce the tax, it would cost money. What purpose would be served if it cost more money to enforce the act, then the act was worth? Also, America was thousands of miles away from England and directing an army across the Atlantic in the 1760s would not be easy. Therefore, Parliament decided using force was not a wise decision.

By 1766, there had been a shift in power in Parliament. The Whigs now had control, but the party would have to wait until Parliament’s next session. In the end of January and beginning of February, reports from America were arriving in England. The Stamp Act was failing and the colonists were still acting violent. That, along with complaints from English merchants about a loss in trade, made Parliament start to consider repealing the Act. “…and Mr. Conway began by summing up the evidence which had appeared before them relative to the decay of the Commerce between.”[25] Still, Parliament was reluctant to repeal the tax because of the colonists’ violent behavior. Had the American people not rioted and burned down the homes of government officials, Parliament may have been more willing to compromise with the colonies at a much earlier time.

George Grenville and William Pitt were the two leaders arguing over the Stamp Act. Grenville was defending his plan, while Pitt was protesting the rights of the colonies. Grenville stated, “…let the Stamp Act be maintained; and let the governors of the American provinces be provided with suitable means to repress disorders, and carry the law into complete effect.”[26] Pitt then replied, “…that we may bind their trade, confine their manufactures, and exercise every power whatsoever, except that of taking their money out of their pockets without their consent.”[27]

With each man finished arguing his point, the members of Parliament moved on to the Declaratory Act. This act would allow the English government the authority to tax the colonies any way Parliament saw fit. “That instructions should be given to those who were appointed to prepare the Bill to preserve the Rights of the British Legislature over the Colonies, and to provide for the erasing and expunging the resolutions of the Assemblies from their books, before the repeal should take place in such respective Colonies.”[28] The Declaratory Act was really a means for Parliament to save face. It almost went against the policy of the stamp tax. Since the Declaratory Act gave Parliament power over taxing colonies, why repeal the Stamp Act because colonists in America were protesting? Obviously, America was gaining power and Parliament was not ready to deal with that issue.

Once they finished discussing the Declaratory Act, the stamp repeal came to a vote. “…at 4 A.M. the motion was carried 275 to 167, for repeal. In the Lords, the vote stood 105 yeas to 71 nays, and on March 18 the King granted his consent.”[29] With the repeal passed, Grenville was defeated and the colonies stood victorious. “There were celebrations everywhere, conducted in a decent and orderly manner, nonimportation agreements collapsed, and many of the distributors were permitted to resume their earlier occupations.”[30]

Grenville would later admit that he was not upset with the colonists’ reaction, but with that of Parliament. The fact that the government would go against its own policy made the colonists believe they were right and Parliament was wrong. “America would not have been in this condition,” he told the Commons on February 1766, “if they had believed that we would enforce the law,” and he ridiculed the Declaratory Act that accompanied the repeal for embodying the notion that Parliament had the right to tax but should refrain from exercising it.”[31] Also, that acting in the manner in which the colonists did proved to be not only acceptable, but successful as well.

The controversy over the Stamp Act was whether Parliament had the right to tax the colonies without their consent. The main reason for the colonists’ success was that they united to fight Parliament’s authority. “Men and women everywhere banded together to render the act as ineffectual as possible.”[32] The issue over authority may not have been so problematic, but colonists had been living under salutary neglect. England was not enforcing the laws Parliament had passed over the colonies for decades. Suddenly, in the early 1760s the government decided to reinforce those laws and the colonists were ready to defend their rights. “Unfortunately the question of Parliament’s power in the colonies, once raised, could not be dropped, and the way in which Parliament went about repealing the Stamp Act demonstrated clearly to anyone with the heart to look, that the difficult decisions of 1765 would continue to be relevant.”[33]

The Stamp Act was only the start of a much larger problem between England and her colonies. Had Parliament been enforcing its laws since they were passed, the issue of who had authority to tax America might have been avoided. However, this was not the case and the colonists fought to protect their rights. Grenville fought to the end trying to save the Stamp Act, but it was to no avail. He warned Parliament that the Declaratory Act would not solve the problem of taxation and representation. Instead, his belief that the act would only make it worse was proven correct by 1776. The colonists had been allowed to self-govern for far too long to start to begin losing that privilege in 1765. Parliament had just started a fight, which would end in civil war with America as the victor.

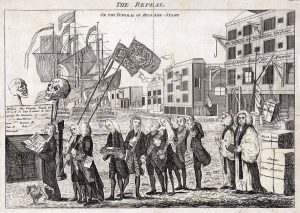

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Burning of Stamp Act, Boston. Source: Library of Congress]

[1] Bruce Ingham Granger, “The Stamp Act in Satire,” American Quarterly 8, no. 4 (Winter, 1956), 368.

[2] Ellen Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1 (Port Washington: Kennikat Press, 1970), 20.

[3] Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 21.

[4] John L. Bullion, A Great and Necessary Measure: George Grenville and the Genesis of the Stamp Act, (Columbia & London: University of Missouri Press, 1982), 183-184.

[5] Charles R. Ritcheson, “The Preparation of the Stamp Act,” The William and Mary Quarterly 10, no. 4 (Oct., 1953), 545.

[6] Ritcheson, “The Preparation of the Stamp Act,” 547, 550.

[7] Ritcheson, “The Preparation of the Stamp Act,” 552.

[8] Ritcheson, “The Preparation of the Stamp Act,” 555.

[9] P.D.G. Thomas, British Politics and the Stamp Act Crisis (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), 91.

[10] Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 23.

[11] Granger, “The Stamp Act in Satire,” 370.

[12] Beverly McAnear, “The Albany Stamp Act Riots,” The William and Mary Quarterly 4, no. 4 (Oct., 1947), 486.

[13] Thomas, British Politics and the Stamp Act Crisis, 100.

[14] For a list of the names of the colonial stamp distributors see: Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 30.

[15] Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 40.

[16] Granger, “The Stamp Act in Satire,”, 373.

[17] Edmund S. Morgan and Helen M. Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1953), 138.

[18] Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 219.

[19] Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 249.

[20] Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 252.

[21] Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 232.

[22] Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 235.

[23] John L. Bullion, “British Ministers and American Resistance to the Stamp Act, October-December 1765,” The William and Mary Quarterly 49, no. 1 (Jan., 1992), 90.

[24] Bullion, “British Ministers and American Resistance,” 95.

[25] D.H. Watson, “William Baker’s Account of the Debate on the Repeal of the Stamp Act,” The William and Mary Quarterly 26, no. 2 (Apr., 1969), 260-261.

[26] For more on Grenville’s speech see: Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 56-58.

[27] Granger, “The Stamp Act in Satire”, 380.For more information on Pitt’s speech see: Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 59-60.

[28] Watson, “William Baker’s Account of the Debate on the Repeal of the Stamp Act,” 264.

[29] Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 64.

[30] Granger, “The Stamp Act in Satire,” 383.

[31] Philip Lawson, “George Grenville and America: The Years of Opposition, 1765 to 1770,” The William and Mary Quarterly 37, no. 4 (Oct., 1980), 562.

[32] Chase, The Beginnings of the American Revolution Vol. 1, 53.

[33] Morgan and Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis, 257.

One thought on “The Stamp Act – A Brief History”

An enjoyable and well researched article on the Stamp Act. However, I am amazed that there is no mention of Patrick Henry and Virginia’s role in the Stamp Act controversy. Unlike the previous meetings of the colonial assemblies who attacked the Stamp Act when it was still being discussed, Henry attacked it after it had become law of the land, when many, like Otis and Franklin, believed it was “a bitter pill” they now must swallow. Patrick Henry’s resolutions declaring that only the elected representatives of the people had the right to tax the people reignited resistance towards the Stamp Act and, as Jefferson stated, “gave the first impulse to the ball of revolution.”